Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

NDIS and emphasis on budgetary control....

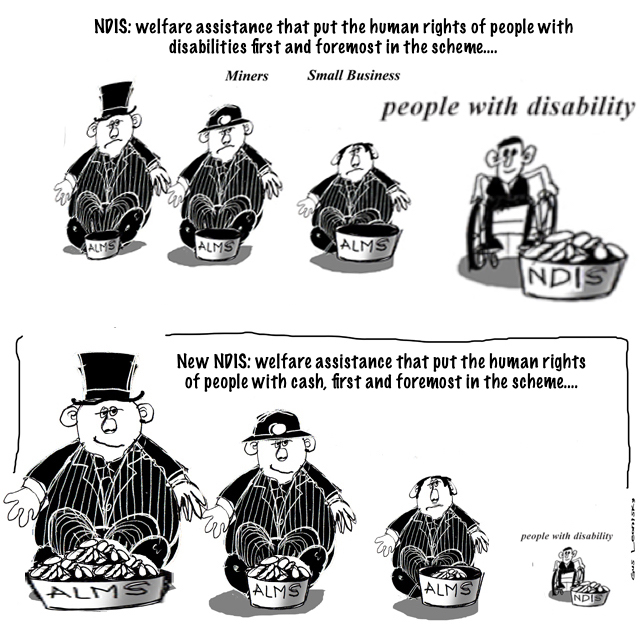

When she introduced the first NDIS legislation to the House of Representatives in 2012 Prime Minister Julia Gillard said it was to replace “A system that metes out support rationed by arbitrary budget allocations, not real human needs”. It was a radical break with other forms of welfare assistance because it put the human rights of people with disabilities first and foremost – not the budget. It was not subject to asset or income tests. It was effectively unique. It was intended to meet Australia’s obligations under the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities.

NDIS and Aged Care; from rights first to budget firstBy Roger Beale

Twelve years later the Government has had a radical change of mind. Now instead of being focused on the rights of the individual to such reasonable accommodation as necessary to secure, in the words of the Convention, “the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity” the Amendments to the NDIS Act introduced to the House place the emphasis on budgetary control. Specifically in this case the changes are to meet in Gillard’s words “an arbitrary budget allocation” of an 8% pa growth in NDIS funding.

How is this to be done? Sam Bennett and Hannah Orban succinctly summarised the volte face: “The Bill performs a sleight of hand with a foundational concept of the 10-year-old NDIS: although the words ‘reasonable and necessary’ persist, they now refer to something else … the level of funding a person gets in their NDIS budget will be ‘reasonable and necessary’, not the individual supports they are funded for. In other words, reasonable and necessary will now refer to your personal spending cap”.

So now, instead of being a bottom up, rights driven approach starting with individual needs the scheme will be governed by a top-down budgetary allocation model with a series of ‘reasonable and necessary’ budgets for each person which will constrain what the individual can fund. Now it looks more and more like the Aged Care framework.

Of course the proposed legislation does some useful things, including in particular acknowledging that a large part of the NDIS expenditure growth has been from children with developmental needs, notably mild autism, and that we need a different way of dealing with this. It also provides the NDIA with the tools to stop rorts.

The noble hopes of the Gillard government have foundered on the rocks of Australia’s bipartisan obsession that we should pay no more tax – even though we sit at the bottom, just above the US, of the OECD tax take as a percentage of GDP. It also reflects the incentive that the States have for cost shifting to the Commonwealth – States have largely dropped their support for the disabled and have failed to expand education services to assist children with early learning difficulties. There have been many suggestions for how the funding to pay for NDIS could be raised ranging from the Royal Commission on Aged Care’s suggestion of an income levy, through amendments to superannuation tax treatment to reduce the cost of tax concessions, or an equitable inheritance tax. All have been explicitly rejected by both major parties.

Consistent with its budget first/rights second approach, the legislation also fails to reflect the Royal Commission’s recommendation to “ensure every person receiving aged care who has a disability can access equivalent supports to those that would be available under the NDIS for people aged under 65 with the same or similar conditions”. This condemns older disabled Australians who are excluded from the NDIS to an aged care system which has funding caps which are acknowledged to be insufficient to support people with severe disabilities to stay in their homes as the vast majority would prefer.

What is scarier still for this group is that the Government is considering legislation which will actually potentially cut the Commonwealth’s support for services to those considered to be “well off” with the gap to be met from their own pocket. There is as yet no definition of what this increased co-contribution will be, or of any regulatory conditions on the maximum fees service providers can charge for the regulated minimum standards. Confusion breeds anxiety and many vulnerable aged disabled people are frightened that they will be extorted by service providers with no recourse.

The bigger question is why is it the aged who are singled out for increased user pays contributions? The usual answer is that, on average, they are wealthier than most other generations and have had access to tax advantaged superannuation. This is lazy ageism. Those aged 55-64 have both higher net wealth and higher incomes than older Australians and people who have lived with disabilities for much of their life have significantly fewer assets and lower incomes. And there are many younger people who are receiving benefits under NDIS who have high incomes and significant net assets – consider Senators Hughes and Steele-John who are both NDIS beneficiaries.

If, as a community, we believe that access to government support should be income/asset tested as an overarching condition, why don’t we make that a universal rule applying equally to the NDIS and Aged Care? And even more radically why do we even have separate programs? Both deal with people who have core activity limitations arising from physical, cognitive or psychosocial conditions, both cover a range of similar supports provided to those living independently and those requiring residential care – so why do we insist that they be treated differently? Food for thought?

https://johnmenadue.com/ndis-and-aged-care-from-rights-first-to-budget-first/

it's time for being earnest.....

- By Gus Leonisky at 20 Apr 2024 - 6:00am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

4 hours 16 min ago

4 hours 38 min ago

6 hours 7 min ago

7 hours 13 min ago

7 hours 39 min ago

8 hours 46 min ago

10 hours 53 min ago

14 hours 46 min ago

15 hours 44 min ago

16 hours 1 min ago