Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the cronulla crapster .....

Shadow Immigration Minister Scott Morrison, known for his hardline approach to border protection, is also the former chief executive of Tourism Australia, a one-time Liberal moderate and a devout Pentecostal. So what maketh the man?

In a country that has always exhibited a fickle streak towards foreigners heading for its shores, Scott Morrison is especially well credentialled to speak on the subject of his shadow portfolio, immigration. The Liberal politician who has spent much of the past 18 months regurgitating the phrase ‘stop the boats’ was also the managing director of Tourism Australia, who asked the rest of the world: ‘Where the bloody hell are you?’ The member for Cook, who counts Desmond Tutu and the anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce among his heroes, reportedly argued in shadow cabinet that the Liberals should exploit community concerns about Muslim immigrants.

The man who attests that his faith has imbued him with “the values of loving kindness, justice and righteousness” also tried to make political hay when relatives of asylum seekers killed in the boat tragedy off Christmas Island in December 2010 were flown at taxpayers’ expense to attend their loved ones’ funerals in Sydney. The Scott Morrison who claims that deterring boat people from ever embarking on the hazardous journey across the Indian Ocean offers the most humane and Christian approach is also the Scott Morrison whose incessant politicisation of the issue has made compromise so difficult. “There is nothing to negotiate,” he said after a vessel carrying 250 asylum seekers sank off the coast of Java in December, adding glibly that Labor had “super-sized” the problem by releasing boat people into the community.

During his maiden speech to parliament in February 2008, Morrison quoted Bono as he made an impassioned appeal for more aid to Africa – hardly a hot-button issue for his constituents in Cronulla. His first words in the chamber acknowledged the Gweagal people of the Dharawal nation, the traditional owners of the land now occupied by his parliamentary seat. Admirers describe him as compassionate, personable, moral and extremely able. Critics take a wholly different view, calling him arrogant, over-ambitious and bullying. “It is impossible to talk about Scott Morrison,” says one, “without dropping the C-bomb.” So with the 43 year old spoken of as a possible future Liberal leader, Australians could be forgiven for asking: ‘Who the bloody hell are you?’

Scott Morrison was born in Bronte in the eastern suburbs of Sydney, now one of the richest enclaves of the country’s richest parliamentary constituency. His family background, however, could hardly be described as part of the elite. Rather, it was strongly Christian and communitarian. His father, John, was a police commander who founded the local Boys Brigade in Bondi Junction, played rugby for Randwick and was an active member of the local RSL. John Morrison was also politically active, serving 16 years on the local council as an Independent and becoming the mayor of Waverley in the mid 1980s. His son’s first political act came at the age of nine, when he handed out how-to-vote cards on behalf of his father.

Scott was an active member of the Uniting Church in Bondi Junction, where his father says he became “a dedicated Christian”. Like his parents, he threw himself into a range of activities – rugby, music, rowing and drama. “He was well liked, a very personable chap,” recalls Reverend Ray Green, who knew him as a child. “He was definitely a leader. People used to follow him around. He was also liked by the girls. There were quite a few in the Girls Brigade who thought he was the ant’s pants.” He met his future wife, Jenny, at church, aged just 12. She had grown up in the St George area of south Sydney, solid battler territory, and used to tease Scott about coming from the posh side of town.

From early on, Scott and his elder brother Alan were instilled with a strong sense of community service (Alan Morrison is now a superintendent in the NSW ambulance service). Scott is a muscular Christian in his father’s mould, and in his zero-tolerance approach towards border protection, perhaps there is something of the police commander as well. Neither did it come as a complete surprise to learn that his bloodline reaches back to Northern Ireland. Whenever I have encountered Scott Morrison, he has reminded me of the Orangemen I used to run into in Belfast, who marched in their tangerine V-shaped collarettes to the thumping beat of the Lambeg drum. Typically they were genial men, of ’50s-era sensibilities, who were prone to defensiveness and flashes of anger on the thorny subject of the border.

Morrison is now a Pentecostal and thus part of the most rapidly growing denomination in the land. He worships at an American-style mega-church called Shirelive in his constituency, where the gospel of prosperity is preached in an auditorium that can accommodate over 1000 evangelicals. With its water baptisms and designer-shirt pastors, Shirelive has close ties with the better-known Hillsong community. The founder of Hillsong, Harley Davidson–riding pastor Brian Houston, is one of Morrison’s mentors. In Who’s Who Morrison lists the church as his number one hobby, and his maiden speech reads in part like a personal testimony delivered on the last night of a church retreat. It included passages from Jeremiah and also the Book of Joel: “Your old men will dream dreams, your young men will see visions.”

A test of his faith came during the period when he and his wife were trying to start a family. It involved repeated courses of IVF treatment and “14 years of bitter disappointments”, but Scott and Jenny were buoyed by their sense of the providential. “God remembered her faithfulness,” recalled Morrison during his maiden speech, as he paid tribute to his wife, “and blessed us with our miracle child, Abbey Rose.” The couple now have two daughters.

While his faith animates his politics, he is on the record as saying “the Bible is not a policy handbook, and I get very worried when people try to treat it like one”. Critics would say that is self-evident from his heartless response to asylum seekers. “I wonder how you can claim to be a serious Christian and take these positions,” said one former colleague. Supporters, however, claim he has pursued a faith-based policy. “He’s a very ethical and moral man,” says a fellow Liberal. “Stopping the boats is ethical and moral.” In his response to December’s boat people tragedy off Java, he advocated a ‘tough love’ policy, which he claimed had the safety of boat people at its heart. After all, for Morrison the Pacific Solution was not only efficient but righteous since it crushed the evil of people smuggling. Church friends might even have seen shades of Wilberforce in his efforts to eradicate such a nefarious trade. To his critics, however, his attacks on the government, which resumed 48 hours after the overloaded boat capsized, offered yet more proof of his harrying opportunism: this was more about political point-scoring than finding a workable solution.

School for Scott Morrison was Sydney Boys High, one of the best in the public sector, while his student years were spent at the University of New South Wales studying economics and geography. That led to jobs in a number of industry groups, including the Property Council of Australia and what was then known as the Tourism Task Force (now the Tourism and Transport Forum). He served as the number two at the TTF before jumping ship to its main rival, Tourism Council Australia. Afterwards, the TTF changed its employment contracts to prevent others from “doing a Morrison”.

When the New Zealand government wanted to set up an Office of Tourism and Sport, it turned to Morrison. Across the ditch, he was associated with the highly acclaimed ‘100% Pure New Zealand’ campaign, but also drew fire from Labor MPs for being the political placeman of the country’s then tourism minister and now foreign affairs minister, Murray McCully. The New Zealand Herald dubbed him McCully’s “hard man”. When McCully resigned his portfolio in 1999, over a scandal involving “golden handshakes” to tourism board members who had resisted his heavy-handed interference, Morrison lost his chief political sponsor. So with a year still left on his contract, he returned to Sydney in March 2000, where he took up a position as the state director of the NSW Liberal Party.

Party chieftains deemed Morrison’s four-year tenure an outstanding success. Though he could never dislodge the state Labor government from power, he revitalised the party machine, and helped the Coalition gain three federal seats from Labor in New South Wales at the 2001 federal election. John Howard said he had never seen the state party better organised.

His reward came after the 2004 federal election, when the Coalition needed a chief executive to head its newly created tourism body, Tourism Australia. In a move that reeked of political cronyism, Joe Hockey, the then tourism minister, gave Morrison the $350,000-a-year post. His reign at Tourism Australia lives in the memory for the troubled ‘Where the bloody hell are you?’ campaign that ran afoul of the British advertising regulator. Fran Bailey, Hockey’s successor as tourism minister, even had to make an emergency trip to London to cajole the British into overturning their ban amid grumbles from her ministry that a closer reading of UK regulations would have alerted Tourism Australia to the problem. Eventually, the campaign worked well in the US, UK and German markets, partly because the controversy surrounding the use of the word ‘bloody’ delivered a bonanza of free publicity. It flopped, however, in Asia, and especially the all-important Japanese market, where the slogan was unfathomable.

Something of a bureaucratic black belt from his days in New Zealand, Morrison also fought running battles with Tourism Australia’s nine-strong board. Its members complained that he did not heed advice, withheld important research data about the controversial campaign, was aggressive and intimidating, and ran the government agency as if it were a one-man show. But Morrison thought he had the upper hand. Confident that John Howard would ultimately back him, Morrison reportedly boasted that if Fran Bailey got in his way, he would bring her down. When board members called for him to go, however, Bailey agreed, and soon it was Morrison who was on his way. “Fran despised him,” says an industry insider. “Her one big win was ousting Scott. His ego went too far.” Another senior industry figure claims that it was Morrison’s arrogance, combined with his misreading of John Howard and the power dynamics of Canberra, that proved his undoing: “He was naive to think he could take on the politicians. Howard was always going to back his ministers.” The “agreed separation” was said to have pocketed him at least a $300,000 payout.

Afterwards, Morrison was given a stopgap role as the “minder” for the then NSW Liberal leader Peter Debnam in the run-up to the 2007 state election. During the campaign, Debnam sported his budgie smugglers at Bondi with such pride that his early morning appearances could easily have been mistaken for a tourism advertisement. Yet even Morrison’s famed organisational skills could not stop Labor from winning in a canter.

Soon Morrison turned his attention to getting himself a seat in federal parliament, and eyed up the safe seat of Cook, which encompasses the Sutherland Shire or ‘God’s Country’, as locals prefer to call it. His friend Bruce Baird, who had been seen as too much of a ‘wet’ by John Howard to be entrusted with a ministry, had decided to step down rather than face what looked like being a nasty challenge from the right of his party. Sure enough, it turned out to be one of the most vituperative preselection campaigns in NSW history, with the right and left factions waging an internecine war. Morrison was not backed by either side – Bruce Baird remained neutral – and he finished a long way back on the first ballot, receiving just eight votes.

Michael Towke, a Lebanese Christian from the right faction, won. Four days later, amid allegations of branch stacking, Towke became the victim of a smear campaign, with a series of damaging personal stories leaked to the Daily Telegraph (after mounting a legal fight, News Limited offered him an out-of-court settlement). There were dark mutterings, as well, that a Lebanese Australian could never win a seat that had recently witnessed the Cronulla riot. The upshot of the smear campaign was that the NSW state executive refused to endorse Towke’s nomination, and demanded a second ballot. The beneficiary was Scott Morrison, a cleanskin in the factional fight, who was parachuted in as a unity candidate. So it is a mistake to presume Morrison is simply an ideal Sutherland Shire man. Local party members initially rejected him, partly because he was considered insufficiently right wing.

Preselection at the second time of asking brought with it the prospect of a safe Liberal seat. In the 2007 election, Scott Morrison was duly elected as the member for Cook, the point of arrival for the first boat people in the history of modern Australia: the crew of the HMS Endeavour.

Scott Morrison presented himself as a Liberal moderate in his first speech to parliament. Not only did he acknowledge the traditional owners, honour Desmond Tutu and William Wilberforce, quote Bono and pay tribute to Bruce Baird, he made reference to Kevin Rudd’s national apology to Indigenous Australians that had brought the chamber to its feet the previous day. “There is no doubt that our Indigenous population has been devastated by the inevitable clash of cultures that came with the arrival of the modern world in 1770 at Kurnell in my electorate,” he noted, and proclaimed himself “proud” of the national apology. Much of the speech could easily have been penned by Malcolm Fraser. His father, John, reckons it reveals the true Scott Morrison: “That speech says what he is and the way he thinks.”

So obviously an up-and-comer, Morrison did not remain on the Opposition backbench for long. Malcolm Turnbull, recognising a fellow traveller from the moderate wing of the party, elevated him to the shadow ministry as the spokesman for housing and local government in 2008. But it was the immigration portfolio handed to him by Tony Abbott in 2009 that provided the vehicle for his rise to prominence.

As the party lurched to the right under the leadership of Abbott, so too did Morrison, and the tourism marketeer proved himself an adept political sloganeer. Gone now was the antipodean Wilberforce of his freshman speech. Instead, he cast himself as a central figure in the Liberal fight-back, much to the annoyance of longbeards in the party who grumbled that he was a first-termer in too much of a hurry. “Supreme opportunism,” scoffed one senior Liberal when I asked about the one-time moderate’s confrontational approach on asylum seekers.

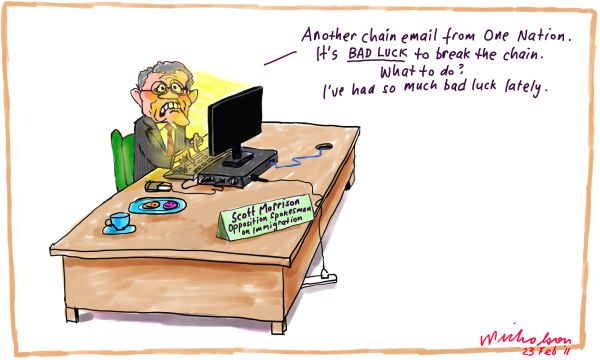

The more publicity that came Scott Morrison’s way, the more hardline he became. So much so that last February, on the morning when victims of the Christmas Island boat people tragedy were due to be buried in Sydney, he launched an ill-tempered attack on the government for paying for family members to make the long journey from Christmas Island. Among them was Madian El Ibrahimy, a detainee at the Indian Ocean detention centre, whose wife, Zman, four-year-old son, Nzar, and eight-month-old daughter, Zahra, had all died at sea. “Do you think you run the risk of being seen as heartless on the day of these funerals to be saying — to be bickering over this money?” asked ABC reporter Barbara Miller, whose report that morning was broadcast on AM. Morrison replied: “When it comes to the question of do I think this is a reasonable cost then my honest answer is, ‘No, I don’t think it is reasonable.’” Seasoned commentators struggled to recall a nastier instance of gutter politics from a senior politician since the heyday of Pauline Hanson. Labor accused him of “stealing soundbites from One Nation”.

Seemingly blindsided, Tony Abbott gave the remarks a lukewarm endorsement when he appeared on Andrew Bolt’s MTR radio program later that morning. “It does seem a bit unusual that the government is flying people to funerals,” said Abbott, though he cushioned his response with genuine sympathy for the survivors. Instead, it was left to Joe Hockey to condemn the remarks: “I would never seek to deny a parent or a child from saying goodbye to their relative.” Then came an acid shower of criticism from party elders. John Hewson called his comments “inhumane”. Malcolm Fraser was scornful: “I hope Scott Morrison is just a fringe element in the party.” More woundingly, Bruce Baird also slapped down his one-time protégé: “I’m very disappointed that Scott would make those comments. It is lacking in compassion at the very time when these people have been through such a traumatic event.”

Morrison also enraged certain members of the shadow cabinet, some of whom seemingly thought he was trying to grandstand his way towards seniority, and then the leadership. At least one exacted revenge by providing damaging leaks from a shadow cabinet meeting the previous December. Chairing the meeting in Tony Abbott’s absence, Julie Bishop had opened up a discussion on which issues should be prioritised in the new year. “What are we going to do about multiculturalism?” Morrison was reported as saying. “What are we going to do about concerns about the number of Muslims?” Morrison later noted: “The gossip reported does not reflect my views,” which fell short of an outright denial.

Morrison declined an invitation to contribute to this profile, but during a lengthy interview on ABC’s Sunday Profile with the journalist Julia Baird, daughter of Bruce, he spoke more about the Christmas Island tragedy. He explained how he regretted the timing of his comments – it was “a very insensitive time for me to have made those remarks” – but not their content. Revealingly, he also recalled how the weekend before, during one of his regular consultations in Cronulla Mall, two pensioners had complained about government waste, and how they themselves no longer felt valued: “And every time they saw money particularly being spent in this area or in the blow-out in costs in [dealing with] asylum seekers and others it really, really offended them.” Here was populism in one of its most unfiltered forms, for Morrison seemed to be suggesting that he was merely a mouthpiece for these elderly constituents. It was not so much a case of dog-whistle politics as megaphone politics.

His comments also provide another vital clue for his lurch to the right: what might be called ‘the Shire factor’. Morrison no doubt recalls how he was rejected in the first round of preselection, and also that the right-wing candidate who beat him, Michael Towke, still controls many of the local branches. What better way for a first-termer to shore up support in Cronulla than to champion the issue of border protection?

Perhaps Scott Morrison entered parliament imagining a very different career, where the nobler instincts of his maiden speech would define his politics. However, the gusto with which he has assailed the government over asylum seekers suggests that his decision to adopt such a hardline stance was morally uncomplicated. He, no doubt, would claim it is simply moral. The boat people issue, where his ambitions and survival instincts intersect, has both advanced his career in Canberra and consolidated his position in Cook. He has become a creature of the capital’s hyper-adversarialism and also of his Cronulla constituents’ parochialism. So while this eastern-suburbs native may not be a product of the Sutherland Shire, he may have become its captive. For Scott Morrison, it is not only a question of how he will be judged by God, but also by ‘God’s country’.

- By John Richardson at 5 Feb 2012 - 9:18am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

4 hours 19 min ago

5 hours 11 min ago

6 hours 29 min ago

8 hours 31 min ago

9 hours 29 min ago

10 hours 39 min ago

11 hours 28 min ago

21 hours 17 min ago

21 hours 29 min ago

21 hours 37 min ago