Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

last man standing .....

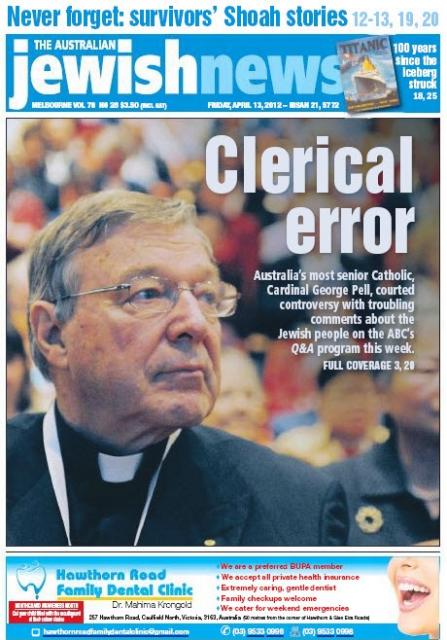

Australia’s Cardinal George Pell gave the worst media performance of his career at his press conference in Sydney on Tuesday. It was lazy, half-hearted and a complete waste of everyone’s time. He looked more than ever like yesterday’s man.

No wonder Pell’s former auxiliary in Sydney, retired bishop Geoffrey Robinson, said on ABC Radio’s The World Today program on Wednesday that George Pell was “an embarrassment”. Bishop Robinson also disagreed with the cardinal about the inviolability of the seal of confessional in cases where a paedophile priest makes a confession to another priest.

Tony Abbott, Australia’s most high-profile lay Catholic, also came out on Wednesday disagreeing with the cardinal on the same issue. “If they become aware of sexual offences against children, those legal requirements must be adhered to,” he told reporters. “The law is no respecter of persons, everyone has to obey the law, regardless of what job they are doing, what position they hold.”

That’s a measure of how isolated Pell now is within the Catholic Church in Australia. It was an extraordinary day for Australian Catholics. But then so was Tuesday, and the day before, when Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced there would be a national royal commission into the sexual abuse of children.

Cardinal Pell’s theme at his unfortunate press conference was that somehow the extent of the crimes had been exaggerated, that some of the claims about predatory clergy might be “fiction” and that the abuse, and the Church’s effort to cover it up, were a thing of the past.

So many of his sentences began well, but ended badly.

“It’s an opportunity to clear the air,” he said, but then added, “to separate fact from fiction.”

“We are not interested in denying the extent of misdoing in the Catholic Church,” he began, but then stubbornly continued: “We object to it being exaggerated. We object to it being described as the only cab on the rank.

“This commission will enable those claims to be validated,” he said, “… or found to be a significant exaggeration.

At one point, he tried to argue that a full inquiry into the monstrous crimes of Catholic clergy was somehow bad for the victims, rather than what it is, a disaster for the Church:

“Now one question I think that might be asked is just to what extent the victims are helped by a continuing furore in the press over these allegations. The pursuit of justice is an absolute entitlement for everyone; that being said, to what extent are wounds simply opened by the re-running of events which have been reported, not only once, but many times previously.”

Cardinal Pell should have been on his knees in front of the cameras begging forgiveness on behalf of the Catholic Church. Instead, he suggested, yet again, that the Church had been the victim of a one-sided smear by an anti-Catholic media.

Does he or anyone advising him seriously believe the Australian public has a shred of sympathy for such nonsense? The Catholic Church is not the victim here. Rather, it is ordinary Catholics who were the true victims of many of the crimes that will come before the attention of the royal commission.

Nor is there any credibility to Pell’s assertion that the Catholic Church has been singled out unfairly by the media. Back in October, child protection expert Professor Patrick Parkinson of Sydney University gave evidence to Victoria’s state inquiry into abuse that the number of offences reported against the Catholic Church has been six times higher than all the other churches combined, “and that’s a conservative figure”.

Even worse for Pell, in a devastating interview this week on ABC Radio’s Religion and Ethics Report, Professor Parkinson, who the Church appointed to review its protocol for handling sex abuse, Towards Healing, announced that he had withdrawn his support for Towards Healing. He has called for a public inquiry into the activities of the Salesian order, and supports the national royal commission.

Cardinal Pell and his minders don’t seem to understand that the problem for the Catholic Church is not victimhood, but failed leadership. Failed leadership is also the reason for the appalling situation that has been allowed to develop — on Cardinal Pell’s watch — at St John’s College at Sydney University, which has virtually been overtaken by a bunch of marauding louts.

As with the sexual abuse crisis, this kind of scandal is what can happen when any institution suffers from poor and neglectful leadership.

The Prime Minister is to be congratulated for announcing the national royal commission. It is what abuse victims and their families have been campaigning for over many years. This inquiry has the potential to be a major international milestone in the response to the sexual abuse of children, just as the Ferns Report (2005), and the Ryan and Murphy reports (2009) were in Ireland. The Government has a responsibility not only to victims and their families, but indeed to Catholics and members of other religious denominations here in Australia. The whole world will be watching, and it will be important to get it right.

This week I spoke at length to two very different advocates on behalf of the victims of clerical abuse. Angela Sdrinis is a solicitor with Ryan Carlisle Thomas Lawyers in Melbourne, and Dr Michelle Mulvihill is a consultant psychologist and a former member of the St John of God Brothers’s professional standards committee, turned whistleblower (more on that Catholic religious order in a moment).

Not surprisingly, their response to the Prime Minister’s announcement of the royal commission is very positive. “It’s fantastic and it’s essential,” says Sdrinis.

Mulvihill says the Prime Minister is “listening to the Australian people, and she’s listening to the urgency of what this means to thousands of victims across Australia.”

Mulvihill says the royal commission will be a good opportunity to “draw a line in the sand, and for every organisation to have their cases taken out of their hands so they’re no longer sitting on their own matters”. But she is sceptical of claims by the Catholic hierarchy that it has cleaned up its act and improved its complaints-handling processes. “The bishops say that in the past they were not very efficient and now they’re okay. I’d like to know when the ‘now’ began.”

Sdrinis and Mulvihill also have a number of concerns that Ms Gillard would do well to heed. In fact Sdrinis has written to the Prime Minister.

In particular, they are concerned that the PM probably does not yet fully comprehend the true scale of misery and horror that the inquiry is likely to unleash on victims and on the Australian public.

“A whole group of people in Canberra who made this decision to hold a royal commission are new to this area. I don’t think they understand yet just how vast an undertaking it is going to be,” says Mulvihill.

She expects that there will be “literally thousands of people turning up to the commission to tell their stories”, and she says there is a danger that the commission will go on for too long.

“Is there going to be a time limit? Victim advocates are saying it could go on for 10 years. Some of the victims and perpetrators will be dead by then, and I don’t think that’s good enough.”

Sdrinis’s firm alone has represented in excess of 1,000 clients, and she warns that nationally in the past half-century, half-a-million Australians were in care as minors.

As a psychologist, Mulvihill is also concerned that the hopes of victims will be dashed yet again if the commission drags on too long. “The commission needs to be time-based, it can’t be allowed to run on forever. If it does, there is a danger that people can get worn out, it’s like battle fatigue.”

She warns that the Prime Minister needs to be aware that much of the evidence that will be presented will be horrific, and says the royal commission must be properly resourced with counselling services — not just for victims reliving the trauma of what was done to them, but also for public servants and others listening to their harrowing testimony day after day.

“There is always a danger of re-traumatising somebody. But on the other hand, if a person doesn’t feel they have been heard in the past, the royal commission may provide a forum where they can begin to leave that trauma behind. Others never leave it. Some people will have high hopes for themselves and not get their dreams fulfilled. This commission must put back-up services in place for everybody.”

Angela Sdrinis says the broad scope of the inquiry presents its own problems, “no doubt about it”.

“But the alternative — just to focus on the Catholic Church — would have been unacceptable. That would have left it open for the Federal Opposition to cry ‘witch hunt’, and we can see the Catholic Church is already doing that. Cardinal Pell talks about anti-Catholic bigotry, but the truth is that this inquiry is a response to decades of frustration and grief.”

Sdrinis says there are “hundreds and thousands” of Australians who were abused, but not by the Catholic Church, who would want to come forward to tell their stories, and that in many instances they will be new revelations that open new lines of inquiry. Many of these will have been children in state-run institutions or foster care.

But Mulvihill and Sdrinis are also adamant that the commission should have the capacity to reach as far back into history as it needs to. “Anyone alive who has a claim should be able to be heard if they wish to,” says Mulvihill. There will be people from the 1930s, 40s and 50s coming forward. Sdrinis notes that her own clients include people who were abused in the 1930s, and says a similar inquiry in Northern Ireland was recently forced to backdate its cut-off date from 1945 to 1922 because so many older people were coming forward.

It will be important for Australian Catholics that the inquiry reach back as far as possible into the past. Catholics have been told by some conservatives in the Church that the abuse that happened was the result of the loosening up of sexual mores in the 1960s, the influx of gays into the seminaries in the 1970s, and even that it was caused by the liberalising tendencies of the Second Vatican Council. The truth is otherwise, of course, but it will be important to demonstrate this as clearly as possible to put minds at rest once and for all.

But Sdrinis says the abuse the commission will hear about is not all in the past: “Underage girls are becoming pregnant in state care even while we speak.” Knowing what we know about how long it takes many abuse victims to find the courage to report their abuse, many of these children may not come forward for decades to come.

One particularly horrific example Sdrinis gives of abuse that does not involve the Catholic Church occurred in Salvation Army homes that were run by paedophiles, unchecked, for decades.

“In the 1970s the Bayswater Boys Home in Melbourne was run by what I would describe as a nest of paedophiles, one of whom has been prosecuted and convicted, another two are currently under police investigation whilst another died whilst facing charges. I am aware of at least 130 complaints of sexual and/or physical abuse. In some cases, the sexual abuse occurred over long periods and was committed by multiple offenders. Whilst these allegations have been investigated by the police, I am concerned that the investigation may not have been as comprehensive as it could have been because police are under-resourced and these claims of historical abuse are very costly and difficult to investigate,” Sdrinis says.

Ryan Carlisle Thomas Lawyers has lodged with the Victorian state inquiry a three-part submission, only one section of which is public. Another section contains several hundred statutory declarations collected from clients. In relation to the Bayswater Boys’ Homes the submission states: “Other allegations that have been investigated by police but not proven are that children were killed at the Bayswater facilities or allowed to die as a result of physical abuse or neglect.”

Sdrinis says that, to avoid duplication, it will be important for the royal commission to begin with a major exercise obtaining and collating all the evidence from other inquiries that is already on the record. These include the Forde Inquiry in Queensland (1999), the Mullighan Inquiry in South Australia (2008), and the current inquiry in Victoria. There have also been three Senate inquiries — into child migrants, the stolen generations, and children in institutionalised care (2009). Western Australia, Tasmania and Queensland also set up “redress funds” to compensate children abused in state care, for which claimants were required to provide statements.

That approach also has its drawbacks. Australian Catholics and the Australian public want to hear Chief Inspector Peter Fox’s allegations of a cover-up in the Maitland-Newcastle diocese sooner rather than later. If a major collating exercise takes precedence, it may be years before he takes the witness stand. And years, too, before evidence under oath is heard from the likes of Archbishop Philip Wilson of Adelaide, retired bishop of Maitland-Newcastle Michael Malone, and Sydney priest and lawyer Father Brian Lucas, who at one time regularly advised bishops on how to handle abusive priests.

What kind of inquiry should the royal commission be? Not a truth-and-reconciliation-style inquiry. “Emotionally, I think we’re past that,” Sdrinis says.

She says the commission will need to be far more forensic in its approach, and that success will depend on its willingness to compel the production of documents “from all the churches and all the state human services departments” — and on using its investigative powers to pursue lines of inquiry. She also warns that documents detailing sexual abuse of children are constantly in danger of being shredded.

“Unless someone takes the step of compelling the production of documents, evidence will be destroyed. In its investigation of the Victorian Government’s record keeping of wards-of-state files, the Victorian Ombudsman found that some of the records were in an appalling state, and that would lead to concerns that boxes of files containing evidence of sex abuse of children in state homes may either have been destroyed or be unable to be found.”

In relation to pursuing lines of inquiry, the royal commission will also have to be prepared to pursue its inquiries beyond Australia’s borders. If it doesn’t, Mulvihill says, “for some of these organisations half the evidence will be missing.” For example, paedophile priest Denis McAlinden was moved to New Zealand and Papua New Guinea. He also spent time in the UK. The Salesians of Don Bosco moved abusing priests offshore to Western Samoa. The St John of God Brothers moved backwards and forwards between Australia and New Zealand, and are also active in Papua New Guinea.

Mulvihill says the Gillard government also needs to indicate whether the terms of reference will include allegations relating to minors in the Australian defence forces and refugees in care.

It will also be important that a decision is made, probably upfront, about whether this commission is going to make recommendations about compensation. Former Irish high court judge Seán Ryan told ABC-TV’s Lateline program on Tuesday that his inquiry was warned by lawyers representing abuse victims that they would not recommend that their clients come forward unless a compensation scheme was put in place.

Michelle Mulvihill says there needs to be some kind of restitution for victims even though “some organisations will be terrified about that”.

“I hope they do offer compensation in many cases, otherwise it’s not going to mean anything. So far, many victims have walked away empty-handed, often because they are vulnerable people whose stories happened too long ago or weren’t believed.”

The Irish Parliament, in my view, missed an important opportunity after the Ryan Report revealed horrific and systemic physical and sexual abuse in institutions run by Catholic religious orders.

The Church should have been forced to close down several of those Catholic orders altogether — even orders with otherwise illustrious histories such as the Irish Christian Brothers. Or else the Dial should have passed legislation seizing their property and declaring them to be illegal organisations in the Republic of Ireland.

Here in Australia, such recommendations should be available and they should be relentlessly pursued. The Catholic Church must be taught, once and for all, that it is not above the law and that it cannot act with impunity.

One Catholic religious order in particular comes to mind. This is the nauseating St John of God Brothers. I first interviewed Michelle Mulvihill in 2007, when she alleged that 75 per cent of the brothers in the order had paedophile allegations against them registered with the police, and that the entire order in Australia was a cesspit of collusion, corruption and denial. Back in 2007, the order had paid out $14 million in compensation to victims and lawyers.

Five years later, nothing has changed. The St John of God Brothers are an international organisation who originally came to Australia from Ireland. According to Michelle Mulvihill, the order is only “in Australia at the invitation of the Archbishop of Sydney, George Pell, and the Archbishop of Melbourne, Denis Hart. Those archbishops should disinvite them and send them back to where they came from.”

And if the bishops have not acted by the time this royal commission is over, the Australian Parliament should have the courage to take whatever action is necessary to close the St John of God Brothers down, along with any other religious orders or institutions whose corruption is judged to be so deep that they cannot be reformed.

- By John Richardson at 17 Nov 2012 - 3:34pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

24 min 16 sec ago

1 hour 34 min ago

2 hours 23 min ago

12 hours 12 min ago

12 hours 24 min ago

12 hours 32 min ago

13 hours 19 min ago

15 hours 17 min ago

15 hours 51 min ago

16 hours 8 min ago