Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

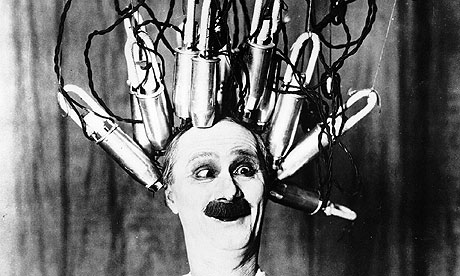

mad science .....

Colonel James S. Ketchum dreamed of war without killing. He joined the Army in 1956 and left it in 1976, and in that time he did not fight in Vietnam; he did not invade the Bay of Pigs; he did not guard Western Europe with tanks, or help build nuclear launch sites beneath the Arctic ice. Instead, he became the military’s leading expert in a secret Cold War experiment: to fight enemies with clouds of psychochemicals that temporarily incapacitate the mind - causing, in the words of one ranking officer, a “selective malfunctioning of the human machine.” For nearly a decade, Ketchum, a psychiatrist, went about his work in the belief that chemicals are more humane instruments of warfare than bullets and shrapnel - or, at least, he told himself such things. To achieve his dream, he worked tirelessly at a secluded Army research facility, testing chemical weapons on hundreds of healthy soldiers, and thinking all along that he was doing good.

Today, Ketchum is eighty-one years old, and the facility where he worked, Edgewood Arsenal, is a crumbling assemblage of buildings attached to a military proving ground on the Chesapeake Bay. The arsenal’s records are boxed and dusting over in the National Archives. Military doctors who helped conduct the experiments have long since moved on, or passed away, and the soldiers who served as their test subjects - in all, nearly five thousand of them - are scattered throughout the country, if they are still alive. Within the Army, and in the world of medical research, the secret clinical trials are a faint memory. But for some of the surviving test subjects, and for the doctors who tested them, what happened at Edgewood remains deeply unresolved. Were the human experiments there a Dachau-like horror, or were they sound and necessary science? As veterans of the tests have come forward, their unanswered questions have slowly gathered into a kind of historical undertow, and Ketchum, more than anyone else, has been caught in its pull. In 2006, he self-published a memoir, “Chemical Warfare: Secrets Almost Forgotten,” which defended the research. Next year, a class-action lawsuit brought against the federal government by former test subjects will go to trial, and Ketchum is expected to be the star witness.

The lawsuit’s argument is in line with broader criticisms of Edgewood: that, whether out of military urgency or scientific dabbling, the Army recklessly endangered the lives of its soldiers - naïve men mostly, who were deceived or pressured into submitting to the risky experiments. The drugs under review ranged from tear gas and LSD to highly lethal nerve agents, like VX, a substance developed at Edgewood and, later, sought by Saddam Hussein. Ketchum’s specialty was a family of molecules that block a key neurotransmitter, causing delirium. The drugs were known mainly by Army codes, with their true formulas classified. The soldiers were never told what they were given, or what the specific effects might be, and the Army made no effort to track how they did afterward. Edgewood’s most extreme critics raise the spectre of mass injury - a hidden American tragedy.

Ketchum, an unreconstructed advocate of chemical warfare, believes that people who fear gaseous weapons more than guns and mortars are irrational. He cites approvingly the Russian government’s decision, in 2002, to flood a theatre in Moscow with a potent incapacitating drug when Chechen guerrillas seized the building and took eight hundred theatregoers hostage. The gas debilitated the hostage takers, allowing special forces to sweep in and kill them. But many innocent people died, too. “It’s been looked at by some skeptics as a kind of tragedy,” Ketchum has said. “They say, ‘Look, a hundred and thirty people died.’ Well, I think that a hundred and thirty is better than eight hundred, and it’s also better, as a secondary consideration, not to have to blow up a beautiful theatre.”

Not long ago, while debating critics of Edgewood on a talk-radio show, Ketchum argued that the tests were a sensible response to the threats of the Cold War: “We were in a very tense confrontation with the Soviet Union, and there was information that was sometimes accurate, sometimes inaccurate, that they were procuring large amounts of LSD, possibly for use in a military situation.” The experiments, he has said, were no more problematic in their conduct than civilian drug testing at the time.

But Ketchum is an unpredictable apologist. His default temperament is that of an unbiased scientist, trying to solve a stubborn anomaly that just happens to be his life’s work. He accepts criticism of Edgewood thoughtfully and admits the possibility that he is seeing the experiments through a prism of benign forgetfulness. At the same time, as Edgewood’s sole public defender, he must relive history under an unforgiving spotlight. Ketchum often hears from aging test subjects looking for information about what the Army did to them. “I need to know everything that happened to me because it could give me some peace and fewer nightmares,” one veteran wrote to him. In such cases, Ketchum responds with a mixture of defensiveness and empathy. “Well, Mike,” he wrote to another veteran, “I guess some people find it satisfying to look back and condemn what doctors and others did half a century ago, especially if it lends itself to sensationalized movies, and entitles them to disability pensions.” Many of his Edgewood colleagues are far less sanguine about what they did; one told me, “I want to see something happen so this doesn’t happen again.” But Ketchum often wins over skeptics. After many e-mails, Mike told him, “I am certain you did the work for the same reason most of us volunteered. It needed to be done.”

- By John Richardson at 11 Dec 2012 - 3:51pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

10 hours 42 min ago

16 hours 18 min ago

19 hours 38 min ago

21 hours 3 min ago

21 hours 16 min ago

22 hours 48 min ago

22 hours 57 min ago

23 hours 44 min ago

1 day 13 hours ago

1 day 16 hours ago