Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

a bunyip aristocracy .....

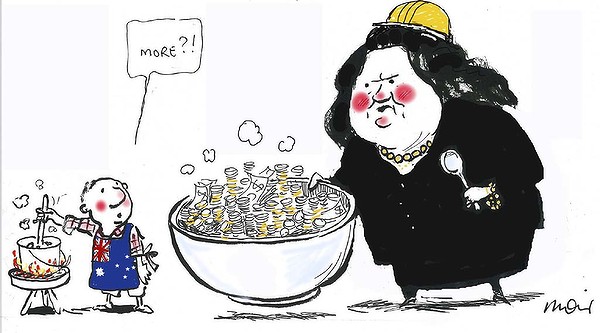

Australia has a long history of romanticising the individuals who make a fortune selling our natural resources, regardless of the cost to the environment. Gina Reinhart, profiled in this stunning New Yorker piece, is part of this tradition, pushing tax-free, economic zones and advocating low wages so she makes a killing. It’s vulture capitalism on crack:

“You vs. gina rinehart,” the banner headline reads on howrichareyou.com.au. The site invites you to enter your annual salary. If you enter sixty thousand dollars, it informs you that Rinehart makes that amount every 1.7 minutes. Below that, a rapidly increasing number calculates how many hundreds of thousands have “landed in Gina’s pocket” since you landed on this Web site. Finally, “Guess who made $107,703 sitting on the toilet today?” Not you. Among the things that her estimated 2011 income could buy: three fully armed Nimitz-class nuclear aircraft carriers; “Jamaica.”

The sheer distorting weight of Rinehart’s wealth is perhaps best understood in relative terms. The American economy is ten times the size of Australia’s, so in the United States an individual fortune equivalent to hers in relation to the national economy would be somewhere around two hundred billion dollars. That is roughly the combined net worth of the four richest Americans. Or seven Michael Bloombergs.

Australians are not known for their deference to the moneyed. I once worked as a pot washer in a casino restaurant in New South Wales. It was a big kitchen, and the pot washers were at the bottom of the job ladder, below even the dishwashers. And yet we made an excellent wage and, as employees, we had entrée to the casino’s private members’ bar, which was on the top floor. We would troop up there after work, tired and ripe, and throw back pints among what passed for high rollers on that part of the coast. Once or twice, my co-workers spotted the owner of the casino in the members’ bar. They called him a rich bastard, and he, in turn, bought us all drinks.

That was 1979. Australia, to my enchanted eye, was a country full of wisenheimers, smart-mouthed diggers with no respect for wealth or authority. Jack’s as good as his master, the saying went—and “probably a good deal better,” Russel Ward wrote in “The Australian Legend.” This skeptical, irreverent, proud self-image was rooted in the early experience of convicts transported from Britain and, later, in labor conflicts with landowners and industrialists. Australia was the land of the fair go—of equal opportunity, and a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work. People used to make fun, in the nineteenth century, of the “bunyip aristocracy”: nouveau-riche Australians who wanted to settle themselves on top of the colonial social heap.

All that is changing. Inequality is on the rise. The share of income going to the top one per cent in Australia has doubled since 1979. (It is still less than half the share going to the top one per cent in the United States. Sixty years ago, the two countries were, by this metric, nearly the same.) According to many critics, including leaders of the current Labor government, Gina Rinehart and her fellow-billionaires pose a direct threat to Australia’s egalitarian tradition.

In 2010, the Labor government introduced a super-profits tax on minerals, hoping to capture more of the mining boom’s lucre for the public purse. Rinehart and her colleagues funded a huge publicity campaign, unprecedented in Australia, against the tax. Rinehart herself, normally so press-shy, stood on a flatbed truck in Perth, wearing a string of pearls, and shouted to a crowd, “Axe the tax!” Within weeks, Kevin Rudd, then the Prime Minister, had been deposed by the right wing of his own party. His replacement, Julia Gillard, came up with a mining tax so watered-down that two of the biggest mining companies operating in Australia have paid nothing to date.

Hancock Prospecting is actually a small company, with some forty employees at its offices in Perth. It collects royalties, looks for minerals, stakes claims, negotiates deals. It litigates, prodigiously, but uses outside counsel. It has no press office. Publicists have been retained as consultants, but never seem to last. The company’s headquarters are in a modest building in a quiet neighborhood in West Perth. By contrast, BHP Billiton, the world’s largest mining firm, occupies thirty-four floors of a forty-five-story building in downtown Perth, and that’s just for its local operations.

Gina Rinehart’s wealth has many sources, starting with her inheritance of Hancock Prospecting, which was worth about seventy-five million dollars, and the old Rio Tinto royalties, which were roughly twelve million a year when her father died and, with increased production and a soaring iron-ore price, have since grown wildly. These royalties will be paid in perpetuity. Rinehart inherited or has acquired the rights to some of the largest mineral leases in the Pilbara, believed to contain billions of tons of minable reserves of iron ore. Hancock Prospecting owns fifty per cent of an iron-ore mine at Hope Downs, in the Pilbara, which opened in 2007. It is operated by Rio Tinto and pays Rinehart’s company, at current prices, around two billion dollars a year. Hancock Prospecting may be minuscule compared with the multinationals, but its value is enormous and Rinehart controls all its shares.

Antony Loewenstein

- By John Richardson at 9 Apr 2013 - 12:33am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

1 hour 56 min ago

2 hours 3 min ago

2 hours 8 min ago

5 hours 46 min ago

9 hours 43 min ago

14 hours 30 min ago

22 hours 43 min ago

1 day 4 hours ago

1 day 5 hours ago

1 day 5 hours ago