Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

boo, it's you ....

It’s not SBY, or East Timor, or terrorist targets: it’s the warrantless snooping on ordinary Australians that can – and does – happen all the time, with very little oversight.

Amid all the outrage about Australia’s foreign-intelligence spooks and their chums at the United States’ National Security Agency (NSA) apparently intercepting phone and email communications with abandon, there is a much greater and more credible threat to accountability and public freedom, almost totally overlooked in the Australian debate.

The real privacy scandal in Australia is that over the past few decades, as telecommunications data has become computerised and centralised, it has become routine for a plethora of government departments to access the private call data of any citizen without having to prove to a judge the need for warrant. This data reveals who someone has been calling, as well as who has been calling them, sending or receiving emails and SMS. It even allows for the location of a mobile phone to be disclosed. All of this extraordinarily powerful surveillance, I emphasise, can be carried out without a judge’s oversight and formal warrant.

This poses a far greater threat to any Australian’s personal freedom than the revelations from former NSA contractor Edward Snowden.

As for the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) – this country’s arm of the so-called Five Eyes UK/USA spying alliance at the centre of the Snowden leaks (formerly known as the Defence Signals Directorate or DSD) – my view is informed by time I spent, 14 years ago, as a journalist talking both officially and unofficially to a wide range of its employees for the Sunday program. That investigation spurred the world’s first admission that the global surveillance network Echelon was real; DSD’s then boss Martin Brady said DSD "does co-operate with counterpart signals intelligence organisations overseas under the UKUSA relationship". Nevertheless I came away more than convinced that the rigid Rules On Sigint And Australian Persons then in place to prevent the interception of Australian citizens’ communications were in fact robust protection against the huge potential for abuse of the spy system. These rules forbid DSD spying on Australians, as well as disseminating any information about Australians – including even their names – that might be accidentally gleaned through foreign-intelligence collection; this is monitored by the Inspector-General. In specific, carefully defined circumstances involving the threat to life, safety or commission of a serious criminal offence, DSD could monitor and report foreign communications involving Australians.

(I have kept in touch with those sources, and their biggest concern about the UK/USA spying alliance is the attitude of American operatives, who have form for misusing their intelligence apparatus for the advantage of US business interests. There is a lingering suspicion, even at senior levels in Australia’s intelligence establishment, that the NSA might be shafting Australia on trade deals and private contracts by giving its own industry a naughty peek at the information it gathers.)

Compare the Snowden leaks with what has been going on in Australia under sections of Australia’s Telecommunications Act which place an obligation on telecomms providers to hand over information to numerous Commonwealth and state-government departments and agencies on the mere assertion that the information is “reasonably necessary” for the enforcement of the criminal law and national security or – and this is where it gets contentious – on even much lesser justification: it also allows access to this private data for the enforcement of “laws that impose pecuniary penalties” or for “assisting the enforcement of the criminal laws in force in a foreign country”, and even merely for “protecting the revenue”.

Aside from requiring a declaration that the information is being sought for a law-enforcement purpose, there is no requirement to say, and therefore no public record of, exactly what crimes are supposedly being investigated using these powers.

The extent of use of these powers is surprising – and suggests that it is being used to shirk the hurdle of judicial oversight. No less than 40 government agencies made 293,501 warrantless requests for metadata from internet service providers in the 2011-12 financial year. Just 56,898 of those requests were made by the Federal Police, which has the primary criminal law-enforcement role. The RSPCA, Wyndham City Council, the Tax Practitioners Board and even the Victorian Taxi Directorate also have been allowed to access individual telecommunications data for a ‘law-enforcement purpose’. Why are we giving quangos and a taxi administrator the power to access often highly sensitive personal telecommunications data?

The Attorney General’s department offers very little explanation of what checks have been done to ensure that this extraordinary data-surveillance power is being used within the law. The department’s annual Disclosure of Telecommunications Data report lists which agencies have been allowed to access to the data, but outlines no oversight of the massive amount of data disclosure now being done without a warrant.

When an agency wants to access the actual content of stored communications it must seek a warrant, and this is under the oversight of the Federal Ombudsman. But what capacity does a Federal Ombudsman or Privacy Commissioner have to review the possible misuse of these broad powers by such a huge range of Commonwealth and state agencies and quangos? It does not appear that there is any actual checking or monitoring done by either the Privacy Commissioner or Ombudsman of the legitimacy of the hundreds of thousands of claims for this data made under the Act.

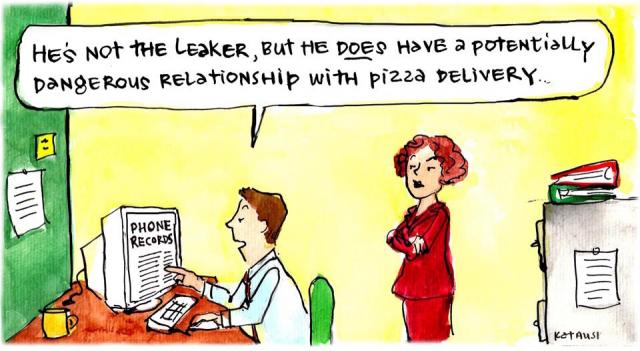

These warrantless data searches are used, wholly justifiably, for criminal investigations – as the Australian Federal Police recently acknowledged was the case in an alleged terrorism arrest. But they have been used also for blatantly political purposes. Ministers have called in the Federal Police to find out how an embarrassing document ended up leaked to the media. While the AFP is an independent statutory authority, it is “guided by Ministerial direction”, making it difficult for an AFP Commissioner to tell a government minister that it’s inappropriate for these data-surveillance powers to be used in a politically motivated leaks inquiry.

These powers can also be used to pursue government whistleblowers. While there is much ado about “open government”, the political culture in Canberra has over many years been about keeping public servants silent about what is actually happening in their departments. Warrantless data surveillance is a powerful way of hunting down and gagging a critic if he or she does dare to leak.

Just about everyone now uses a mobile phone or an email account, but few people consider how easy it is to track calls.

Journalists investigating allegations of dodginess in government have found themselves, and their sources, under investigation – little realising that their source had been compromised by a quick check of the journalist’s phone records. This warrantless data-disclosure power is a serious impediment to freedom of the press, and its potential for misuse is a serious threat to the public interest. Proponents of this warrantless power might argue that there is no evidence of abuse, but how can anyone monitor or complain about the use of this power if most people do not know when it is used? How much scrutiny really is done of the nearly 300,000 such requests for data annually, to test the merits of the public-interest and law-enforcement claims for disclosure?

I have seen how this happens; some years ago I was investigating a story involving alleged impropriety by a senior government official in a major federal government department. The multiple sources I was talking to (mercifully, off the phone) were providing me with leaked documents and information that raised serious questions of possible impropriety, if not corruption, which we subsequently broadcast. One source, it turned out, was tech-savvier than I am. He worked in the internal investigations unit of the department and knew what could be done to investigate any public servant who leaked information to the media. He told me it was likely there would be an inquiry into the source of the leak for my story, and that the minister would most likely order a Federal Police investigation into whom the leak had come from – and that the first thing the AFP would then do is access my phone records. We agreed never to call or email each other because that would lead investigators straight to him as my source. Surveillance of my phone and email data was all but inevitable, he said. “Surely they’d need a warrant to do that?”’ I asked. Within hours of this conversation my savvy source – no doubt improperly – obtained a copy of my mobile-phone call data, showing the numbers I had called and which of those numbers belonged to a federal government public servant.

He told me no one had ever questioned him or any of his colleagues about the requests they made for phone-call data; if there was any kind of oversight, he’d never seen evidence of it. I can only hope the accountability checks have improved in the past 12 years, because both the Ombudsman and Privacy Commissioner are nominally the check on executive abuse of such private information. But it does strain credibility that every one of the 300,000 such annual requests for “law enforcement” purposes would be scrutinised.

In November, Federal Police Commissioner Tony Negus admitted his force had accessed the call data of “up to five” members of parliament. Negus made much of the judicial oversight, through the issuing of a warrant, for any interception of the contents of phone calls, emails or SMS messages – but the elephant in the room was his admission that up to five MPs had been the subjects of warrantless data-surveillance, and that no judge had any input at all regarding the propriety of this access. Negus did not say who the MPs were but, aside from the two MPs who have been the subject of criminal investigations, Craig Thomson and Peter Slipper, it is likely the requests also targeted leakers inside the public service.

Having been on the receiving end of at least one such AFP investigation I know AFP officers loathe being diverted from their serious criminal investigative work onto political leaks inquiries, for instance the now abandoned investigation into who in Prime Minister Gillard’s office allegedly leaked a damaging video of Kevin Rudd swearing at his staff. Such use, or abuse, of the data-surveillance powers is completely legal under Australian law; I am assured also that it is routine.

Earlier this year a Parliamentary Committee on Intelligence and Security recommended strengthening the safeguards and privacy protections in these telecommunications laws. The committee recommended changing the objectives of the Act to “protect the privacy of communications” and to “enable interception and access to communications in order to investigate serious crime and threats to national security”. It also recommended the use of a proportionality test that would take into account “the privacy impacts of proposed investigative activity; the public interest served by the proposed investigative activity, including the gravity of the conduct being investigated; and availability and effectiveness of less privacy intrusive investigative techniques”.

One telecommunications provider, IINET, also complained to the committee that the scope of the law enforcement obligation, “to give such help as is reasonably necessary”, is “vague and uncertain”. The effect of this obligation is to unfairly put the onus of testing the validity of a surveillance request on to the employees of the telecommunications company that receives it.

Thus far the Committee on Intelligence and Security’s recommendations for a review have been ignored. Attempts to curtail warrantless spying are frequently opposed by government bureaucrats, who use the mantra that such constraint would seriously curtail national security and criminal investigations. Yet even the Attorney General’s Department, in its own submission to the committee, admits the need for reform, saying that, “As communications technology and use has changed, some data types have become more privacy intrusive. Access to the more privacy intrusive ‘traffic data’ could then be limited to those agencies that have a demonstrated need to access this information for undertaking their investigative functions. The less privacy intrusive category of ‘account-holder data’ would be available to the broader range of enforcement agencies.”

The most effective control on executive power is strict, open accountability on how power is being used – but since most Australians do not understand the capacity of this surveillance technology, nor can they find out what supposed offences it is being used to investigate, they are hardly in a position to complain about it.

As the AFP admitted in its submission to the Parliamentary Committee, the data it can obtain without warrant potentially includes a mobile phone caller’s location, their IP addresses and URLs. There is no doubt that such powers can be properly used to great effect in a criminal terrorism or corruption investigation, but should they be able to be used by any public-service investigator with a so-called law-enforcement purpose given the derisory accountability checks currently in place to stop their abuse?

As so often happens, accountability controls set up to protect privacy have not kept up with the pace of technological change. The capacity to log an individual’s call data, to cross-match that instantaneously with whom that person is calling or emailing would have been unthinkable decades ago, when these laws were first drafted. History shows such powers will eventually be abused.

- By John Richardson at 14 Dec 2013 - 5:00pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

1 hour 41 min ago

3 hours 48 min ago

4 hours 33 min ago

5 hours 59 min ago

7 hours 1 min ago

7 hours 27 min ago

17 hours 15 min ago

17 hours 31 min ago

21 hours 30 min ago

22 hours 57 min ago