Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

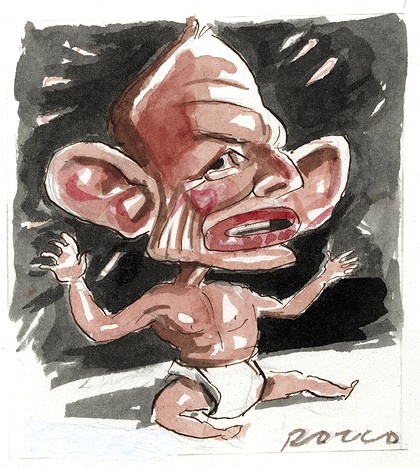

hollow man .....

The adolescent country. The bit player. The shrimp of the schoolyard.

For Australians it's not so bad - most of the time - to be so far away, so overlooked, so seemingly insignificant as to almost never factor in major international news. The lifestyle makes up for it.

But occasionally, there's an awkward, pimply youth moment so embarrassing that it does sting. Like when 19 of the world's most important leaders visit for a global summit and Prime Minister Tony Abbott opens their retreat on Saturday with a whinge about his doomed efforts to get his fellow Australians to pay $7 to see a doctor.

Advertisement And then he throws in a boast that his government repealed the country's carbon tax, standing out among Western nations as the one willing to reverse progress on climate change - just days after the United States and China reached a landmark climate change deal.

The Group of 20 summit could have been Australia's moment, signalling its arrival as a global player, some here argued. But in all, the summit had Australians cringing more than cheering.

It was a classic example of what Fairfax Media journalist and Australian author Peter Hartcher calls the "pathology of parochialism" in a recent book, The Adolescent Country. Hartcher argues that the nation's politicians rarely miss a chance to trump important foreign policy matters of long-term national interest to score cheap domestic political points.

"The big matters are commonly crowded out by the small," the Fairfax journalist argues. "International policy is used for domestic point-scoring."

Opposition leader Bill Shorten called Abbott's opening G20 address "weird and graceless."

"This was Tony Abbott's moment in front of the most important and influential leaders in the world and he's whingeing that Australians don't want his GP tax," said Shorten, referring to the $7 fee.

It's a tendency some observers argue not only damages the country's credibility but Australians' ability to take themselves seriously.

Historians such as Geoffrey Blainey, who wrote The Tyranny of Distance in 1966, explained Australia's "cultural cringe" and parochialism as a product of the continent's historic isolation and vast distance from the colonial power, Britain. The title became an explain-all catchphrase. But almost 50 years later, with China and other Asian powers rising, Australia leaning toward its Asian neighbours, and NATO dominance waning, surely Australia had grown up?

Hartcher believes that Australian politicians have lately squandered opportunities to strengthen the country's global position at the time of a major global power shift.

"The great crises that threaten Australia's national prosperity come from abroad," he wrote. "So do the grandest opportunities. But the reflex in Australia's national politics is that where these biggest stakes come into competition with the smallest, the small are the ones that very often win.

"Measured against its potential today and its needs tomorrow, Australia is seriously underperforming and it is underperforming because of the pathology of parochialism."

In a book about Australia last year, the BBC's former Sydney correspondent, Nick Bryant, said parochial politics had been taken to the point of absurdity and "the party room has trumped the halls of international summitry".

After the July shooting down of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, widely blamed on pro-Russia Ukrainian separatists, Abbott publicly vowed to "shirt-front" Russian President Vladimir Putin - a term conveying a chest-to-chest male physical confrontation. After orchestrated Western pressure and pointed slights against Putin at the G20, the Russian leader reportedly planned to leave early.

Since his election last year, Abbott has also taken a tough line with China, his country's biggest trading partner. He offended the world's most populous Muslim country and one of Australia's closest and most important neighbours, Indonesia, over his handling of his policy to turn back boats carrying would-be asylum seekers from countries such as Afghanistan, who often depart from Indonesia.

In the lead-up to the G20 summit, the conservative Abbott insisted climate change would not be on the agenda, only to be wrong-footed by the US-China climate change deal and President Barack Obama's pledge to contribute $3 billion to a fund to help developing countries deal with the effects of global warming.

"Australia has a choice," said analyst Michael Fullilove, director of the Lowy Institute for International Policy, a Sydney-based think tank, in a recent article, noting the country's shrinking diplomatic corps and military. "Do we want to be a little nation, with a small population, a restricted diplomatic network, a modest defence force, and a cramped vision of our future? Or do we want to be larger: a big, confident country with the ability to influence the balance of power in Asia, a constructive public debate, and a foreign policy that is both ambitious and coherent?"

For some, the G20 moment stung all the more after a memorial service this month for a reformist Australian, former Labor Party prime minister Gough Whitlam, who died in October at 98. It was a day of stirring speeches, with nostalgia for a time when leaders had sweeping ideas of the country's identity, vision and place in the world and weren't afraid to spell them out in grand, compelling speeches.

Don Watson, a speechwriter for Labor's former prime minister Paul Keating, said recently that great speeches took words and ideas seriously.

"Funnily enough, not many in politics do anymore" in Australia, he said. "I mean, the main objective, one would think from listening to politicians now is to try to remove the meaning from words, to make them as anodyne and dull as possible, not to generate human interest but to squash it."

Australia suffers another cringeworthy moment during G20 summit

- By John Richardson at 17 Nov 2014 - 4:46pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

2 hours 12 min ago

2 hours 52 min ago

3 hours 15 min ago

3 hours 33 min ago

4 hours 35 min ago

9 hours 47 min ago

10 hours 10 min ago

13 hours 6 min ago

1 day 2 hours ago

1 day 4 hours ago