Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

when the adults take charge ….

One week after Tony Abbott was elected in September 2013, the “possum-infested” Lodge was undergoing renovation and Australia’s new prime minister was looking for temporary accommodation. Abbott’s choice – a modest flat in the Australian Federal Police (AFP) College in Canberra – saw him “bunk down” with AFP recruits. The residence appeared to have everything the prime minister needed: heavy security and a gymnasium. The Murdoch press was elated, trumpeting its hero’s frugality and common sense. Sydney’s Daily Telegraph ran a 2010 photo of a beaming Abbott surrounded by NSW police officers. (Presumably any police force would do.) Abbott was in his element. Clad in a load-bearing police vest complete with radio, torch and taser gun, he was ready for operational duty.

In February this year, after barely surviving a backbencher revolt, his leadership seemingly in freefall, Abbott was back in the arms of the law as he delivered his “National Security Statement” at AFP headquarters in Canberra. No police vest this time, and no questions allowed. Only the cameras, a wall of Australian flags, and a handful of police, military and ASIO officials in the presence of a grim-faced, impossibly rigid man who appeared more like a commander-in-chief than a prime minister. In a solemn decree, Abbott warned Australians of the “heightened terrorism threat”. “The number of potential homegrown terrorists is rising,” he intoned. He spoke of “hate preachers” and “foreign fighters” who would soon have their citizenship stripped, punishment for their support for the ISIS “death cult”.

Unmistakably and irresponsibly, Abbott was stoking fear.

Having already been invaded psychologically, Australia was apparently on a war footing. The prime minister personally promised to keep “our country safe” with the same “clarity of purpose” he had demonstrated in “Operation Sovereign Borders” and “Operation Bring Them Home”. Soon he was announcing yet another operation, this time a joint one in which 333 Australian and 143 New Zealand soldiers – “the splendid sons of Anzacs” – would support a two-year mission training the Iraqi military to fight the “death cult”. Although Australia is at best an aspiring middle power in the fight against ISIS, the prime minister’s hawkish denunciations of the enemy make Tea Party Republicans appear meek. Abbott is Australia’s General manqué.

Conventional wisdom dictates that Abbott’s bellicose posturing is merely a desperate ploy to secure his political survival, but this is only part of the explanation. Toughness, the language of war and the deliberate cultivation of a siege mentality in the electorate have defined Abbott’s prime ministership more than that of any of his Liberal predecessors, even John Howard. The author of Battlelines and How to Win the Constitutional War, the protégé of Bob Santamaria and the confidant of George Pell – warriors par excellence – knows no other way. For Abbott, politics is war. His vision of government is instinctively defensive and prosaic. Rather than using power creatively, he relies on his enemies to define his agenda. Abbott is not a leader so much as an enforcer. As he thundered early last month, “We think that anyone who raises a gun or a knife to an Australian because of who we are has utterly forfeited any right to be considered one of us.”

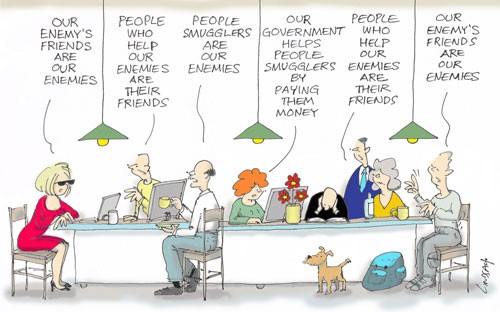

An undeniable crudeness and a breathtaking parochialism accompany this tough façade. Faced with the humanitarian crisis of the Rohingya asylum seekers, Abbott’s response to the question of resettlement in Australia – “Nope! Nope! Nope!” – was simply astonishing for its lack of empathy, more akin to that of a shrill backbencher than a prime minister. Faced with Neil Mitchell’s incredulity that Australian officials were alleged to have bribed people smugglers to tow boats back to Indonesia, Abbott blithely stated that the government would stop the boats “by hook or by crook”, as if hypocrisy, immorality and Australia’s obligations under international law were of no concern. These failures of leadership will define Abbott’s legacy. The brutal truth is that Abbott is not only the worst conservative prime minister since Billy McMahon. He is an embarrassment.

Much has been written about the government’s cavalier attitude towards the rule of law, its determination to control the flow of information and silence criticism, and the dramatic increase in state surveillance and detention powers. Judging by Abbott’s proposal to allow the executive rather than the courts to determine evidence of an offence when revoking citizenship, both the prime minister and Immigration Minister Peter Dutton would also fail Question 15 of the government’s own practice citizenship test:

Which arm of government has the power to interpret and apply laws?

a) Legislative

b) Executive

c) Judicial

Abbott and Dutton have circled “b” but the answer, of course, is “c”.

In recent weeks Abbott’s zealous approach has gone far beyond political point-scoring and come to threaten the very fabric of Australian democracy. It has subverted cabinet, compromised the doctrine of the separation of powers, and pushed the Liberal Party away from its moderate conservative foundations towards a populist, reactionary, anti-democratic frontier. This will fundamentally alter the party’s image and, in the process, damage the body politic and the country’s standing internationally.

If Australians were asked to design a constitutional system from scratch, Abbott wrote in 1995, one of the things they would demand is “strong checks and balances on the executive, because even the best government sometimes gets too big for its boots”. He now appears deaf to the principles that saw him enter federal parliament in 1994. The politician who built his political career defending constitutional monarchy has done more than any other prime minister to undermine the Westminster system of government, increasing executive power at the expense of basic democratic freedoms.

It’s important to note, too, the counterproductive nature of the government’s essentially punitive approach to foreign fighters, one that will surely result in entrenching grievances within the radical fringes of the Muslim community. Rather than flexing his muscles for public display, a more intelligent response from Abbott would be to take the heat out of the issue by engaging the Muslim community. To prevent more danger, the government would seek to understand why foreign fighters choose to leave; how they might be drawn off the battlefield or brought to justice rather than cut loose; and, finally, how they might be rehabilitated, where possible, in order to persuade others not to follow in their footsteps. In Denmark, a country with the second highest number of foreign fighters per capita in Europe, the city of Aarhus has introduced a program to assist combatants’ reintegration into the community and succeeded in stemming the flow of fighters to Syria.

What Abbott sees as strength – shirt-fronting terrorism on talkback radio, threatening imprisonment and proposing that dual nationals be stripped of their citizenship at the immigration minister’s discretion – is actually a sign of weakness. He is only capable of responding to complex policy issues as an attack dog. As former Liberal minister Amanda Vanstone stressed, “Cutting down our democratic protections to get at the enemy is profoundly dumb. We end up doing the enemy’s work for them, and from within.”

No one doubts that the threat of terrorism is real. But Abbott’s alarmist rhetoric – “terrorists are reaching out to our community” – is out of all proportion to any realistic assessment of Australia’s vulnerability. And the consequences for Australia are becoming more serious as each month passes. Rising above the complaints about executive overreach of the proposed changes to citizenship laws and the shameless attacks on Human Rights Commission president Gillian Triggs is the constant din of Abbott’s drums of war and the incessant harping on the spectre of terror. The result is a more insular and frightened country, an electorate with little willingness or determination to grapple with a raft of political, social and economic issues that require urgent attention. Even discussion about the outcome Abbott claimed he would “sweat blood” to achieve – constitutional recognition of indigenous Australians – has been muffled in the talk on terror.

In his maiden speech to federal parliament on 31 May 1994, Abbott was overwhelmed by the occasion: “Mr Speaker, standing before you in this chamber, which is heir to 700 years of parliamentary tradition, I feel like a very small boy in a very big school.” The boy is still there. Australia desperately needs better leadership.

Citizenship and its discontents

- By John Richardson at 2 Jul 2015 - 8:18am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

1 hour 9 min ago

11 hours 20 min ago

13 hours 11 min ago

13 hours 13 min ago

14 hours 18 min ago

17 hours 39 min ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 2 hours ago