Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

Scomo’s ‘voodoo economics’ …

Following a sponsored visit by Reagan adviser Arthur Laffer, Malcolm Turnbull’s budget is based on the fallacy of his trickle-down economics.

The story goes that in 1974, at the Two Continents restaurant of the Hotel Washington, a conservative economist named Arthur Laffer met with two rising stars in the Republican Party, Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld.

As they ate, they talked economics. The United States was in a recession at the time, and Laffer sketched out on a serviette something which became famous as the “Laffer curve”.

Bloomberg media, in a story that reunited the three men 40 years later to share recollections of the historic meal, described this curve as “the napkin doodle that launched the supply-side revolution”.

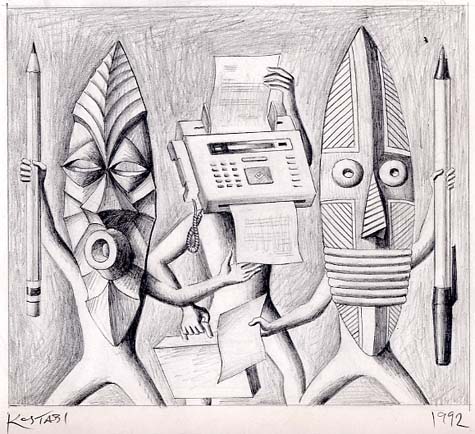

Laffer’s theory became an article of faith among certain economists, politicians and, of course, business leaders and wealthy individuals. It goes by various names: supply-side economics; trickle-down economics; Reaganomics; or, in the famous phrase of president George Bush snr, voodoo economics.

The fundamental premise of Laffer’s argument was simple. If the rate of tax is zero, the government gets no money. But if tax rates are 100 per cent, the government also gets no money, because no one bothers to work. Somewhere between those extremes there had to be an optimal point that maximised both the return on endeavour and government revenue.

Laffer suggested that by cutting tax rates, government would stimulate economic activity and ultimately benefit from higher revenue. And the whole economy would benefit from – and this phrase might sound recently familiar – a boom in jobs and growth.

Laffer became an economic adviser to President Ronald Reagan, who proceeded to implement his prescription. Reagan progressively cut taxes, including reducing the marginal rate from 70 per cent to 28 per cent. British prime minister Margaret Thatcher also became a devotee, again employing Laffer, and from there the “tax cuts spur growth” philosophy spread.

And no wonder. You may have heard economist J. K. Galbraith’s famous quote that conservatives are engaged in one of mankind’s oldest exercises in moral philosophy: “that is, the search for a superior moral justification for selfishness”.

The Laffer curve provided one. Give the wealthy more, it said, and all will benefit.

Rates of economic growth were higher when corporate taxes were higher.

More than 40 years later, Laffer is still spruiking his economic vision and is still beloved of the rich and tax averse. Only last year the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry brought him to Australia to assist in their campaign for lower business taxes. They took him to Canberra, where he did the rounds of government.

He met with many key figures, particularly at a lunch with an informal grouping of Liberal Party free marketeers called the Modest Members, one of whose co-chairs, Kelly O’Dwyer, has since become assistant treasurer. The other co-chair is Scott Ryan, now minister for vocational education and skills.

Former assistant treasurer Josh Frydenberg tweeted a picture of himself grinning with Laffer.

John Osborn, former chief operating officer and now economics policy adviser to the chamber of commerce, and Laffer tour organiser, also arranged for him to speak to the usual right-wing think tanks – the Institute of Public Affairs and Gerard Henderson’s Sydney Institute – as well as to various media outlets.

Some interviews went better than others. On St Patrick’s Day, Laffer was interviewed by Fran Kelly on ABC Radio National Breakfast, where he boasted that Reagan’s adoption of his policy gave the US “the most phenomenal economy of all time, [the] best recovery in US history”.

Kelly challenged him: “That’s a pretty rosy view of the Reaganomics there. The critics would say the biggest impact of those Reagan tax breaks was to double the US deficit to $155 billion and triple government debt to more than $2 trillion.”

Laffer made excuses. There had been a lot spent on defence. The deficits were “nothing” compared with those of more recent US administrations. But he acknowledged Reagan had not done enough to cut spending. He also said that when it came to encouraging enterprise and growth, “All taxes are bad, Fran.”

Kelly had put her finger on one of the big flaws of the supply-side theory, though. Far from maximising revenue to government, it reduces it. Therefore, its proponents argue, government should get smaller. But voters demand government services and so governments increasingly take on debt.

An OECD study from last year, “Sovereign Debt Composition in Advanced Economies: A Historical Perspective”, illustrates the phenomenon graphically. The debt-to-GDP ratio of all major nations had fallen sharply from its peak in World War II until the 1970s. Then, coincident with the ascent of the supply-siders, it began to rise. And then rise even faster after the global financial crisis. By 2010 – the end point of the OECD numbers – it had trebled. It continues to zoom upwards even as economies sink into deflation.

1. “Jobs and Growth”

For decades, the dominant belief was that if you look after the rich it will ultimately benefit all, but there is actually precious little evidence that is true. To the contrary, there is growing evidence that it does the exact opposite and increases inequality, which in turn reduces economic growth. The empirical data are increasingly leading people to the conclusion that the current global malaise is substantially a consequence of misplaced faith in trickle-down economics.

Which is where the 2016 budget comes in.

In the 30 minutes of Treasurer Scott Morrison’s budget speech on Tuesday night he uttered the phrase “jobs and growth” 13 times. It was said many times more before and afterwards.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, and other members of his government, also chant the mantra endlessly.

Why are they giving $5.3 billion of tax cuts to business over the next four years and, as Treasury revealed on Friday after several days of obfuscation from the government, $48.2 billion as the cuts apply to ever-larger businesses over 10 years? To encourage “jobs and growth”.

Why are they giving $4 billion worth of tax cuts to the top 25 per cent of income earners over the next four years? “Jobs and growth.”

Why are they cutting the taxes of the top 2 per cent of income earners – those on more than $180,000 a year – by a further 2 per cent, at a cost of about $1.2 billion?

Why is the government prioritising tax cuts for high-income earners over other things, such as health, education, welfare, the environment, et cetera?

It’s always the same reason: “jobs and growth”.

It’s the classic supply-side argument: reduce tax and regulation on capital, and the benefits will flow down to all.

How else can you explain the spending priorities of the 2016 budget, summed up in three figures by the chief economist of The Australia Institute, Richard Denniss? “Forty-seven per cent of the value of those personal tax cuts goes to the top 1 per cent of income earners. Seventy-five per cent goes to the top 10 per cent. Zero goes to the bottom 65 or so per cent.”

It’s harder to determine how much of the business tax cuts will flow to top-income earners, in part because not all small and medium businesses are equally profitable and in part because so many of them are dodging tax anyway.

One can safely assume, however, that most of the benefit of the budget’s tax cuts will flow to wealthy people, even if their tax returns don’t fully indicate that wealth.

It has to be done, though, because, as Morrison said on Wednesday night: “If we wish to continue to see our living standards rise with more jobs and higher wages, we need to ensure our tax system encourages investment and enterprise.”

2. Tax cuts and inequality

But do lower tax rates result in stronger growth?

In 2012, the US Congressional Research Service, a non-partisan body charged with advising US lawmakers, set out to “clarify” whether there was any association between the tax rates paid by the highest income earners and economic growth.

It found no correlation.

That’s pretty amazing when you consider it was comparing the current low US tax rates with postwar rates above 90 per cent.

There was no conclusive evidence, the report found, of “a clear relationship between the 65-year steady reduction in the top tax rates and economic growth. Analysis of such data suggests the reduction in the top tax rates have had little association with saving, investment or productivity growth.”

But the report was even more damaging for supply-siders. It also found that “the top tax rate reductions appear to be associated with the increasing concentration of income at the top of the income distribution”.

In other words, tax cuts did not encourage growth but did promote inequality.

In Australia, according to analysis from the Australian Council of Social Service, inequality grew more rapidly between 2000 and 2008 than in all but two other developed countries.

The council also highlighted some other indicators of increasing inequality. Over the 25 years to 2010, real wages increased by 14 per cent for those in the bottom 10 per cent of the income distribution range compared with 72 per cent for those in the top 10 per cent.

And wealth is far more unevenly distributed than income. The top 20 per cent have about 70 times more wealth than the bottom 20 per cent. The top 10 per cent of households own 45 per cent of all wealth; the bottom 40 per cent of households own just 5 per cent of wealth.

A recent OECD report on the subject noted that beyond its impact on social cohesion, “growing inequality is harmful for long-term economic growth”.

It estimated the increased inequality in the 20 years to 2005 knocked 4.7 percentage points off growth. The “key driver” it found, was the growing gap between the bottom 40 per cent on income earners and the rest.

Do we need business tax cuts to encourage jobs and growth?

Bureau of Statistics data, crunched by The Australia Institute, show that since 1960 private business investment in Australia has trended slowly down as a share of GDP. The interesting thing is that corporate tax rates have jumped around a lot over those 55 years.

Before Australia caught the Laffer bug in the late 1980s, they averaged well above 40 per cent. Then they came down in a series of steps to 30 per cent. But there was no more investment as a result.

The same long-term trend is even more apparent in economic growth. The supply-siders would have us believe that lower corporate taxes would, as Turnbull repeats endlessly, lift growth. The reverse is the truth. Rates of economic growth were higher when corporate taxes were higher.

Up to 1988, under the higher corporate tax regime, the economy grew by 3.8 per cent a year on average. Thereafter, it dropped to 3 per cent. In recent years, it has been lower still. The estimate for the coming year is 2.5 per cent.

As for tax cuts boosting jobs and wages, the data shows unemployment rates were lower when corporate taxes were higher, and that since those company rates have been lowered, the share of GDP accruing to capital has risen significantly and that going to wages has declined.

In short, business is inclined to simply pocket the benefits of tax cuts.

3. Stiglitz responds

Forty years of supply-sidism, says Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, have now inflicted on the world “the economics of this inertia”.

He says it is “easy to understand, and there are readily available remedies. The world faces a deficiency of aggregate demand, brought on by a combination of growing inequality and a mindless wave of fiscal austerity. Those at the top spend far less than those at the bottom, so that as money moves up, demand goes down.”

Stiglitz’s answer: “An increase in government spending matched by increased taxes stimulates the economy.”

But that is not what Laffer was preaching when he sat down with members of the government last year, in his black suit and silver tie, still selling his napkin theory to whomever would listen. And it is Laffer’s prescription, rather than Stiglitz’s, that Turnbull and Morrison have offered in their budget.

Reagan ‘voodoo economics’ at the heart of Scott Morrison's budget

- By John Richardson at 7 May 2016 - 6:11pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

1 hour 2 min ago

2 hours 34 min ago

5 hours 17 min ago

5 hours 23 min ago

5 hours 36 min ago

8 hours 13 min ago

8 hours 36 min ago

10 hours 39 min ago

12 hours 7 min ago

1 day 6 hours ago