Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

you want bullshit with that ...

The year 2016 is likely to be recognised as one of those great turning points of modern history, even more than 1979, 1989 and 2001. Democracy faces its greatest existential crisis since the 1930s. What is sometimes called “the Enlightenment project” has come under sustained attack in the United States, much of Europe, and to a lesser degree, so far, Australia.

Donald J. Trump’s election as the 45th president of the US marked the beginning of a new political era – post-truth, post-evidence, post-courage – which is particularly confronting, considering that Americans, like Europeans and Australians, are part of the most highly educated cohort in their history, on paper, anyway. The truth of a proposition means nothing, and evidence is irrelevant.

Paradoxically, in the US, much of Europe and Australia, as levels of formal education rise, and information is readily available on an almost infinite number of issues, debate becomes infantilised and reduced to the narrowly economic and personal. There appears to be an inverse relationship between available knowledge and the operation of political systems.

At present there is a serious withdrawal from political engagement by people with high levels of education or professional skills.

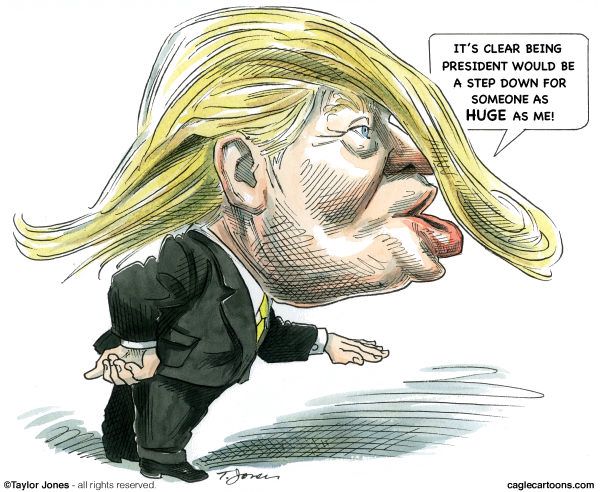

The principal elements in any Trump speech are the ranting style; endless repetition, reminiscent of the Bellman in Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark: “What I tell you three times is true”; reliance on slogans; the adoption of “truthiness”; inconsistency; hypersensitivity to criticism; vulgar abuse of opponents; use of childish language; sense of improvisation, as if he doesn’t know what he will say next; and lack of empathy or understanding of other points of view. For Trump, the most important subject is himself, something he returns to constantly, often referring to himself in the third person.

Obviously many voters, but not a majority, see that style as authentic, and they identify with it.

Disconcertingly, he claps himself as he comes on stage, a distinctly North Korean touch. His presentation is reminiscent of Mussolini and Kim Jong-un.

But the most worrying factor about Donald Trump is his complete lack of curiosity. On the issues raised with him in the campaign, he either knows the answers already or he has no desire to hear the elements of discourse – the case for and against a proposition. He has surrounded himself with “yeasayers” who are of the one mind. He looks to simple solutions for complex problems. He seems to be bored by or hostile to science. He sees the environment as a barrier to development and employment.

Trump is unreflective, posturing in a way that may conceal deep insecurity, narcissistic, always personalising issues to the hero versus the devil. He talks – shouts, really – in slogans, endlessly repeated, with no evidentiary base. He appeals to fear, anger, envy and conspiracy theories. He is an incorrigible tweeter.

I grew up with the conviction that activists observed a problem, collected evidence, worked out a strategy, explained it, sought reactions, addressed objections or criticisms, corrected errors, then sought to act. Even after legislation was enacted, it still had to be explained until the community understood and accepted it. Now this approach seems obsolete. Evidence doesn’t matter. If you don’t like the facts, somebody can find alternative facts.

Malcolm Fraser, in his controversial period as prime minister from 1975 to 1983, was often seen as rigid and remote, although always good on race and refugees. After his defeat in 1983 he became increasingly progressive, resigning from the Liberal Party in 2009. On some issues, such as the republic referendum of 1999, he formed an unlikely alliance with Gough Whitlam, collaborating in campaigns.

He thought that both the Coalition and the Labor Party had become corrupted and timid, looking for immediate advantage, adopting a narrow focus on economics, as if humans could be defined as consumers only, as homo economicus; that the goals of life were entirely material, and that great long-term issues, involving the fate of the planet and non-commercial values, could be ignored.

In our conversations late in his life, Fraser hypothesised that a new political force could emerge out of the ashes of the two major parties.

I proposed the “Courage Party” as a working title for a new political force, although Fraser had some doubts about the name. It would not have been a “centre party”. It would not have been the sort of party that explored policy differences between the major parties – when any could be found – then split the difference, opting for something safe, in the middle, offending nobody. It would have been radical, more so than other parties on most issues, dedicated, to quote the Polish political philosopher Leszek Kołakowski, “to a number of basic values, hard knowledge and rational calculation”.

Fraser used his formidable networking skills to invite experts in foreign policy, taxation, defence, environment, science, health, education and law reform, including drug laws, to prepare detailed position papers, analysing evidence, proposing long-term solutions to intractable problems. All agreed. Each expert was dismayed by the failure of both government and opposition to act courageously on the great issues of our time.

Mike Richards – political scientist, author, former associate editor of The Age, who worked happily as chief of staff to John Cain and Simon Crean, and unhappily with Mark Latham – collaborated with Fraser in exploring alternative political structures and policy formulation.

Then in 2015 came two dramatic changes.

In March, Fraser died, unexpectedly. In September, Malcolm Turnbull displaced Tony Abbott to become prime minister. He traded a promise of inaction on contentious issues that he had advocated in his first period as Liberal leader and elsewhere in his life, such as climate change and the republic, to secure the votes he needed to defeat Abbott. This meant adopting most of Tony Abbott’s policies, as Abbott was quick to point out.

Membership of both the Liberal and Labor parties has become small and sclerotic. Public funding and compulsory voting are bomb shelters that protect the existing hegemonic parties and make reform virtually impossible. Most electors are loyal to the major parties on polling day but many cast their vote with pegs on their noses.

The creation of nationwide factions in the late 1980s led to the “privatisation” of Labor, in which factional leaders became traders and conviction politics was replaced by retail – or transactional – politics.

The central question about policy was no longer “Is it right?” but “Will it sell?” Factions are essentially executive placement agencies – and the members of each owe their primary allegiance to the faction or subfaction. Loyalty to a faction, or subfaction, is more important than commitment to a principle or ideal. Parties have become closed corporations, oligarchies. Political operatives have become traders.

Some citizens share the delusion that left and right are fighting tooth and claw on major issues and that there is a deep ideological divide in our parliament. This is not only wrong, but absurd. The bitterest fights in parliament are not on major issues, but on personalities, relative trivialities and “gotcha” moments.

Within the hegemonic political parties there are factions often described as “left” or “right”, but in practice these are just labels.

There is no significant difference between left and right on refugees, on taxation, on coal, on gambling, on a federal anti-corruption body, a bill of rights, a republic, on preservation of the ABC and CSIRO, on planning a post-carbon economy, on foreign and defence policy and the surveillance state. Or if there is one, I haven’t noticed.

The need for policies based on evidence, analysis and statistics is disputed by many, who prefer to rely on instinct, feelings and intuition, for example on global warming or refugees.

The treatment of refugees is described as “operational”, coded language for saying that the subject cannot be discussed. Neither of the two political oligarchies competing to form government will open up debate on the subject – so that evidence or statistical analysis is not just suppressed, it is treated as irrelevant.

There is too little dispute with this. It is as if voters say: “We are powerless. There are thousands of party insiders and only 15 million of us…”

Nature, notoriously, abhors a vacuum. At present there is a serious withdrawal from political engagement by people with high levels of education or professional skills. They have deserted the field of action with disdain, wringing their hands, expressing dismay or even contempt for the political process, but refusing to engage. I can understand those feelings but they lead to a deformation of how democracy works. The politics of reason are being displaced by the politics of frustration and anger.

There are at least two possible alternative models for a third political force. One on the left, one on the right.

Model A: This could be the Courage Party. It would be significantly based on our 4.5 million graduates, including professionals, teachers, performers, writers, artists, social workers, scientists, doctors, intellectuals and other knowledge workers. It would probably attract Greens supporters, frustrated reformers from Labor and some unhappy progressive Liberals. Unions and professional associations might affiliate. Its policies would be essentially evidence-based and it would emphasise finding solutions to what sociologists call “wicked problems”: refugees, a new taxation system, a post-carbon economy, biota sustainability, needs-based funding for education, ending toxic political culture.

Model B: We could call this the Left Behind Party. Its common elements are identifying victims and denouncing enemies; resentment about rapid change; nostalgia about the past; apprehension about the future and many aspects of modernity; responsiveness to fear about the unfamiliar, especially mixing with other races and cultures, particularly Muslims; finding simple explanations for complex problems. A Model B party has these characteristics: rejection of evidence, low levels of formal education, resentment of elites and “political correctness”, and a belief the 1960s was a “Golden Age of full employment”. Many of these voters used to be with the Labor Party but now are often, but not always accurately, identified with a nativist populism.

The Model B phenomenon resonates in the small towns and rural areas of most states. Unhappily, it may be the more likely prospect if the major parties – for all their deficiencies – fail.

Model B supporters are visible, and vocal. Model A supporters exist, but have other priorities and are not to be seen.

Great crises often produce great leaders – Lincoln, Churchill, Roosevelt, Curtin – but Australia, like most other Western nations, does not have heroic leadership on offer. Instead, our leaders are essentially followers. They lack courage and vision, and fail to explain, explain, explain to win public support on difficult issues. Instead, they read Newspoll obsessively and say, timidly, “I am their leader. The people will tell me what I must do.”

The precondition for a Courage Party would be courageous people prepared to sacrifice time, effort, money and thought, driven by strong convictions, knowledge and ethics.

Posterity will judge our generation harshly if we fail to act.

The need for a new political party | The Saturday Paper

- By John Richardson at 17 Feb 2017 - 3:01pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

16 min 19 sec ago

1 hour 47 min ago

2 hours 6 min ago

3 hours 45 min ago

4 hours 44 min ago

4 hours 48 min ago

5 hours 34 min ago

5 hours 44 min ago

6 hours 4 min ago

6 hours 16 min ago