Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

nothing new......

A general that Vladimir Putin recently hailed the ‘Hero of Russia’ has reportedly been removed from his position as Moscow’s invasion faces embarrassing setbacks.

Britain’s Ministry of Defence said General Alexander Lapin had been sacked from the role, the fourth senior commander to have been pushed aside since the war began.

It follows a pattern of senior military officials copping the blame for Mr Putin’s floundering war to “deflect blame from Russian senior leadership at home”.

“If confirmed, this follows a series of dismissals of senior Russian military commanders since the onset of the invasion in February,” the UK intelligence said.

“Lapin has been widely criticised for poor performance on the battlefield in Ukraine.

“These dismissals represent a pattern of blame against senior Russian military commanders for failures to achieve Russian objectives on the battlefield.”

READ MORE:

https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/2022/11/07/hero-of-russia/?breaking_live_scroll=1

YES, PUTIN IS "FLOUNDERING"?..... WE DO EXPECT A BIT BETTER REPORTING FROM THE NEW DAILY, BUT THE STENCH OF AMERICANA IS PERMEATING ALL THE WESTERN SEWERNEWS OUTLET....

SO FAR GUS HAS NO INDICATION THAT PUTIN IS "FLOUNDERING" (TURNING INTO A FLAT FISH...) BUT IF YOU WISH TO KNOW ABOUT GENERALS BEING SACKED FROM THEIR JOB, WE DID NOT HAVE TO GO MUCH FURTHER THAN AFGHANISTAN....

Looking back on the troubled wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, many observers are content to lay blame on the Bush administration. But inept leadership by American generals was also responsible for the failure of those wars. A culture of mediocrity has taken hold within the Army’s leadership rank—if it is not uprooted, the country’s next war is unlikely to unfold any better than the last two.

By Thomas E. Ricks

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2012/11/general-failure/309148/

BUT HERE IS A REMINDER, OF WW2 AND THE VIETNAM WAR, FROM 10 YEARS AGO:

If you’re looking for management lessons from outside the halls of corporations, you could do worse than to study the United States Army. That master of management teaching Peter Drucker often turned to the military of his adopted nation for inspiration, especially on matters of leadership. Take, for example, this advice from his 1967 book The Effective Executive:It is the duty of the executive to remove ruthlessly anyone—and especially any manager—who consistently fails to perform with high distinction. To let such a man stay on corrupts the others. It is grossly unfair to the whole organization.It is grossly unfair to his subordinates who are deprived by their superior’s inadequacy of opportunities for achievement and recognition. Above all, it is senseless cruelty to the man himself. He knows that he is inadequate whether he admits it to himself or not.

The first example Drucker cited of such wise practice came not from the business world of the 1960s but from the army of the 1940s. Its leader, General George C. Marshall, he wrote, “insisted that a general officer be immediately relieved if found less than outstanding.”

Ironically, by the time Drucker was writing, the army had lost the practice of swift relief that Marshall had enforced so vigorously. With regard to talent management, it was already beginning to teach a different kind of lesson—a cautionary tale. To study the change in the army across the two decades from World War II to Vietnam is to learn how a culture of high standards and accountability can deteriorate. And to review the extended story of its past six decades is to comprehend an even deeper moral: When standards are not rigorously upheld and inadequate performance is allowed to endure in leadership ranks, the effect is not only to rob an enterprise of some of its potential. It is to lose the standards themselves and let the most important capabilities of leadership succumb to atrophy.

The Right People in the Right Jobs

In General Marshall’s day, perhaps it was easier to agree on a clear notion of what constituted success in the leadership of the armed forces. It may have been a more straightforward exercise to consider whether one general was driving toward that goal more or less effectively than others. That may in fact be why a man as understated as Marshall, reticent to the point of seeming almost colorless, was able to rise to the level he did. He was a classic transformational leader—an unlikely figure of quiet resolve who can reinvigorate and redirect a company or an institution. Consider Marshall’s low-key demeanor on September 1, 1939, the day that World War II began in Europe. That same day he formally ascended to chief of staff of the army—a far more important position then than it is now, partly because it included the army air force. “Things look very disturbing in the world this morning,” he commented drily in a note that day to George Patton’s wife. Even after the war, and his obvious success, he lived on a modest government salary and turned down lavish offers from publishers who wanted him to write his memoirs.

Certainly George Marshall was not a political animal or a Washington courtier. One subordinate, General Albert Wedemeyer, called him “coolly impersonal.” He was distant even with his commander in chief, President Franklin Roosevelt. He made a point of not laughing at the president’s jokes and was clear that he preferred not to be addressed by his first name. He didn’t visit Roosevelt’s home in Hyde Park, New York, until the day of FDR’s funeral.

In the spring of 1939, even before becoming chief of staff, George C. Marshall had devised a plan to remove scores of officers he considered deadwood.

When Marshall is remembered nowadays, it is more often for his role in establishing the Marshall Plan, which revived the economies of post–World War II Europe, than for his role in the preceding war. Yet he was unwavering, even fierce, in doing what needed to be done to win that war. He stands as an extreme example of leading not by being charming or charismatic but by setting standards.

Few overhauls are as sweeping as the one Marshall oversaw: the creation of the American superpower military, the globe-spanning mechanized force that we have come to take for granted over the past seven decades. On the day in 1939 that he became chief of staff, the U.S. Army was a small, weak force of about 190,000 men—“not even a third-rate military power,” as he later wrote in an official Pentagon report. Of the nine infantry divisions the army had on paper, only three were at divisional strength, while six were actually weak brigades. Six years later, when he stepped down, the army numbered almost 8 million soldiers and had 40 divisions in the European theater and another 21 in the Pacific.

As transformational leaders tend to do, Marshall began by focusing on people. He truly was ruthless in getting the right people in the right jobs—and the wrong people out of them. When Brigadier General Charles Bundel insisted that the army’s training manuals could not all be updated in three or four months and instead would require 18, Marshall twice asked him to reconsider that statement.

“It can’t be done,” Bundel repeated.

“I’m sorry, then you are relieved,” Marshall replied.

In the spring of 1939, even before becoming chief of staff, Marshall had devised a plan to remove scores of officers he considered deadwood. By his estimate, he eliminated some 600 officers before the United States entered the war, in December 1941. Another wave of firings came just after the attack on Pearl Harbor, with the top naval, army, and air commanders for the Pacific removed. A year later the commander of one of the first divisions to fight the Japanese was fired. So, too, was the senior tactical commander of the first American divisions to fight the Germans in Africa.

Those removed were replaced by younger, more vigorous officers, such as Dwight D. Eisenhower, who as late as 1940 was still a lieutenant colonel serving as the executive officer of an infantry regiment. Marshall put the new men through a series of tests. At each level those who faltered were shunted aside. First, each man had to be given command of a unit. The next question was whether he would be allowed, once the unit was trained, to take it overseas and into combat. Then, once in the fight, a commander had a few months in which to succeed, be killed or wounded, or be replaced. Of the 155 officers allowed to command army divisions in combat in the war, 16 were relieved for cause. Yet Marshall’s policy of swift relief had a forgiving aspect: The removals were not necessarily career-ending. Indeed, five of the relieved division commanders were given other divisions to lead in combat later in the war.

It was a dynamic and hard-nosed system of personnel management—and it worked. For an army, a key marker of excellence is adaptability—grasping a changing situation and making good decisions in response to it. Allies and enemies alike observed that the distinctive characteristic of the U.S. forces in World War II was that given how much they had to learn, they did so very quickly. Bernard Lewis, later an influential historian of the Middle East, took away from his time as an intelligence officer in the British army two dominant impressions of the Americans. “One was that they were unteachable,” he wrote in The Atlantic in 2007. But “what was really new and original—and this is my second lasting impression—was the speed with which they recognized [their] mistakes, and devised and applied the means to correct them. This was beyond anything in our experience.” Similarly, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the most famous German general of the war, found it “astonishing…the speed with which the Americans adapted themselves.”

“Can’t Execute My Future Plans with Present Leaders”

Just five years after World War II ended, as the army found itself fighting in Korea, it seemed to have lost that adaptability. Twice in 1950 the same force that had taken on the Nazis and the Japanese empire was driven down the Korean peninsula by poorly equipped peasant armies. First, in the summer, it was harried south by North Korean forces; then, in late autumn, it was surprised by the Chinese army.

Lieutenant General Matthew Ridgway, another of Marshall’s protégés, was dispatched at the end of 1950 to try to turn the war around. On his first morning in Korea, the hawkeyed Ridgway climbed into the bombardier’s compartment of a B-17 to fly over and study the rugged terrain of the peninsula. Later that day he visited the South Korean president. Next, and most important, he spent most of three days visiting his battlefield commanders. He was shocked to find that the quality of leadership of American troops was often as poor as their morale. Commanders had not studied the ground on which they were fighting. They had kept their troops on the roads instead of putting them up on ridges. And they had failed to coordinate with units on their flanks. “The troops were confused,” Ridgway wrote in Military Review in 1990. “They had been badly handled tactically, logistically.”

How is it that an officer corps known for its excellence could be infiltrated so quickly by mediocrity? The focus on one clear goal, and who was best equipped to pursue it, was lost, and the criteria for leadership evaluation became muddied by other considerations. One of the problems in Korea was that the army was trying to give officers who had been stuck in staff jobs in World War II a chance to command in combat, in part out of a sense of fairness, and in part to help season the officer corps in case of a war with the Soviet Union.

Ridgway acted decisively. Discovering that the army’s headquarters in Korea was some 180 miles south of the front lines, he ordered it moved closer to the fighting. He also decided to remove several of his senior commanders. “Can’t execute my future plans with present leaders,” he informed the army chief of staff in a note. Over the following three months he would relieve one corps commander, five of his six division commanders, and 14 of his 19 regimental commanders. Ridgway shortly succeeded in turning around the war; it was an episode of transformational leadership that would be better known had it not occurred in a small, unpopular conflict on the other side of the earth.

Yet Ridgway could not uphold the Marshall system of managing generals as thoroughly as he wished. Relieving high-ranking officers of their commands did not sit as well in a controversial “police action” as it had in World War II, in part because of the politics of the war. Ridgway’s first firing of a general set off alarms at the Pentagon. Soon a senior general was cabling him that “what has the appearance of wholesale relief of senior commanders…may well result in congressional investigation.” Ridgway was ordered to back off a bit and to disguise the moves he made as part of a normal rotation process.

No one could know it at the time, but this episode would prove to be the death knell for relieving battlefield generals in the U.S. Army—and the beginning of a precipitous decline in accountability.

A Plunge into Institutional Self-Interest

If the focus on choosing leaders who could win wars was compromised by political considerations in the Korean conflict, it was thoroughly subverted in the Vietnam era. After Korea the army as an institution was adrift. Some seriously questioned whether ground forces even had a role to play in the era of nuclear weapons, which were revolutionizing the air force and the navy. The air force was rapidly expanding. Shortly after the Korean War it fielded its first genuinely intercontinental bomber, the B-52. It was also moving smartly into space with the first wave of reconnaissance satellites. The navy introduced the first nuclear-powered submarine, the USS Nautilus, and then developed an intermediate-range nuclear-tipped missile, the Polaris. By 1959 the army’s allocation of the Pentagon budget was 23%, exactly half the air force’s share.

Scrambling to justify its existence, the army came up with a new role for itself. If the air force and the navy were focusing on atomic war, at the high end of the conflict spectrum, the army would move to the low end, the area historically occupied by the Marine Corps. General Maxwell Taylor, the army’s chief of staff during the second half of the 1950s, began a new emphasis on “brushfire wars.” To prepare for engagement in such small conflicts, he established a “special warfare school” at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

President Eisenhower had vigorously resisted becoming involved in clashes on the remote edges of the communist world, insisting in 1956 that “we would not…deploy and tie down our forces around the periphery in small wars.” But his successor, John F. Kennedy, was intrigued by General Taylor’s ideas and brought Taylor into the White House, where one of his first assignments was to consider how to handle the deteriorating situation in South Vietnam. If ever there was a case for doing adequate research before entering a new and strange market, Vietnam was it—especially because little if any evidence existed that the army would be able to adapt to its markedly different requirements. It is not overstating the case to say that America’s doomed venture there grew in part out of the army’s search for a mission in the mid-1950s.

It is extraordinary to think that the same men we lionize as part of “the Greatest Generation” we demonize—and rightly so—for their part in the debacle in Vietnam. These men were not just survivors; they were winners who had risen quickly in World War II to become, while still in their twenties and early thirties, commanders of battalions and regiments. In an army of millions, they had been star performers, standing astride the globe at the end of the war. Yet it was not clear that they were the right men to lead the army in Vietnam.

This generation of officers was led by Taylor, who had commanded the 101st Airborne Division during World War II. Though retired, he was named military adviser (a new and unusual post) to President Kennedy and then, in 1962, recalled to active duty to be chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Taylor would prove to be almost the opposite of Marshall. Where the latter had kept his distance from the White House, Taylor made it his base of power. Marshall had insisted on candor and had given it to the president. Taylor, by contrast, had a tendency toward mendacity. He played on distrust between generals and marginalized the members of the Joint Chiefs. He also encouraged the selection of notably stupid men to command the war in Vietnam—first Paul Harkins, and then William Westmoreland.

Thus the Marshall system of generalship saw its collapse in Vietnam. Honesty and accountability were replaced by deceit and command indiscipline. A force that in World War II had been lauded for its adaptability proved agonizingly slow to recognize the nature of the war in which it was engaged. When fighting among the people, the army should have used firepower far more discriminatingly and should have considered it a last resort rather than a default mode. And where relief of command had once been seen as a sign that the system was working as designed, in Vietnam it became seen as a challenge to the system itself. Almost no generals were fired in Vietnam. Had Peter Drucker been able to peer into the process, he might have observed that it was “grossly unfair to the whole organization.”

The loss of relief may have been the key to other problems. When real success goes unrewarded and failure to take initiative goes unpunished, the entire incentive system for risk taking is undercut. As Wade Markel, an officer, a student of military history, and now a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation, has put it, an army that had once been eager to exploit opportunity now worked instead to avoid error. Most firefights were initiated by the enemy, who was rarely pursued. “Pursuit became a forgotten art,” Lieutenant General (Ret.) Dave Richard Palmer observed in Summons of the Trumpet, the best operational history of the Vietnam War. “No sizable communist force was ever hounded to its lair and wiped out.”

Perhaps just as damaging, when inadequate leaders are allowed to remain in command, their superiors must look for other ways to accomplish what needs to be done. In Vietnam close supervision—what today we call “micromanagement”—became commonplace in the army. It is no coincidence that one of the enduring images of that conflict is of small-unit leaders looking up to see their battalion, brigade, and even division commanders hovering over them in helicopters. General Frederick Kroesen, who fought in that war as well as in World War II and Korea, wrote in Army magazine in 2010, “In Vietnam, many low-level commanders were subject to a hornet’s nest of helicopters carrying higher commanders calling for information, offering advice, and generally interfering with what squad leaders and platoon leaders and company commanders were trying to do.” This not only undercut combat effectiveness but also denied small-unit leaders the opportunity to grow by making decisions under pressure.

Once accountability had been compromised by the deflection of focus onto what was good for the army, it was a short step to a corrosive focus on what was good for present company. This is an important but rarely noted lesson of the My Lai incident. Today people recall the massacre on March 16, 1968, of some 400 Vietnamese peasants, 120 of them children aged five or less, as the horrific result of a rogue platoon’s being led by a dim-witted lieutenant. What is forgotten is that the army’s subsequent investigations—which, to its credit, were exhaustive—found that the chain of command up to the division commander, Major General Samuel Koster, was involved either in the atrocity or in its cover-up. Battalion commanders hovered overhead as the operation was carried out, and the brigade commander, Colonel Oran Henderson, later filed a report falsely stating that 120 Vietcong soldiers had been killed at My Lai.

The cover-up lasted more than a year and was broken only when a former enlisted soldier began reporting to civilian officials what he had heard about the murders and rapes that took place that day. General Westmoreland, by then kicked upstairs to be army chief of staff, rose to the occasion and insisted on a thorough inquiry. He appointed Lieutenant General William Peers, a World War II veteran who had led the 4th Infantry Division in Vietnam, to investigate.

Operating under extreme time pressure, because the statute of limitations would soon apply to many lesser crimes, Peers and his staff conducted more than 400 interviews. Peers was an old friend of Koster’s, yet he found the division commander’s testimony “almost unbelievable” and was shocked by the web of lies he uncovered. “Efforts were made at every level of command from company to division to withhold and suppress information,” he concluded. The thoroughness of the deceit made Peers wonder what had happened to the values of the army he had served all his adult life: Dozens of officers knew that something awful had happened at My Lai, yet it was an enlisted soldier who finally had the courage to blow the whistle. Peers’s official report named 30 soldiers, including two generals and three colonels, who appeared to have committed offenses in the cover-up, which included the wholesale destruction of documents. He concluded that Koster was guilty of conspiracy, making false statements, and dereliction of duty.

The generals of the Vietnam era had ceased to behave like stewards of their profession and were more like keepers of a guild, taking care of their own.

Yet the army’s leaders shied away from acting decisively on those shocking findings. Lieutenant General Jonathan Seaman, who was selected to decide the disposition of the case against Koster, chose not to court-martial the general and instead gave him the minimum punishment possible: demotion to brigadier general and a letter of reprimand. Koster, who had brought perhaps more disrepute on the army than any general since Benedict Arnold, was allowed to remain in the service, wearing the uniform he had disgraced, until January 1, 1973. Peers told Westmoreland that he considered this “a travesty of justice.”

If My Lai was the modern low point of army conduct, the generous treatment of the leaders involved in it was the nadir of the army’s leadership culture. The contrast with George Marshall’s insistence on strict accountability and his sense of responsibility to the American people could not be starker. Anyone looking into the army would have found its ranks riven by racial tension, drug use, and indiscipline. Its relationship with its civilian overseers, and indeed with the American people, was in tatters. “The Army was really on the edge of falling apart,” remembers Barry McCaffrey, who stayed in the service despite its troubles and rose to become a four-star general. And no wonder: The generals of the Vietnam era had ceased to behave like stewards of their profession and were more like keepers of a guild, taking care of their own.

The Lingering Cost of Mediocrity

When the process by which leaders earn and keep their positions loses its integrity, the loss extends far beyond poor outcomes achieved locally. Across the system the ability to do the top-end work of leadership begins to atrophy. Leadership requires high-level strategic thinking about what to do as well as tactical guidance on how to do it. The army’s failure to rigorously uphold standards left its senior leadership with shortcomings in strategic thinking that became evident in the deserts of Iraq and Afghanistan.

In the 1970s and 1980s the army was given a sweeping overhaul. It shifted from conscription to recruitment to fill its ranks. It underwent a revolution in training and weaponry. It revamped its doctrine on how to fight. Less noticed at the time, and still largely unrecognized, was that this overhaul occurred at only one level. Focused on teaching the force better tactics to get its job done, army leaders gave short shrift to strategic thinking. They didn’t recognize the distinction between winning battles and the more difficult task of winning wars.

In Iraq and Afghanistan, U.S. troops fought their battles magnificently. They were well trained, well equipped, and part of cohesive units—one reason the relatively small army did not fall apart under the strain of fighting those two lengthy wars. Yet the new body had an old head. The troops were led by generals who surprisingly often seemed ill equipped for the tasks at hand, especially the difficult but essential job of turning victories on the ground into strategic progress. Four times—in 1989 in Panama, in 1991 and 2003 in Iraq, and in 2001 in Afghanistan—army generals led swift and successful attacks against enemy forces without a notion of what to do the day after their initial triumph. In fact, they believed that it was not their job to consider that question. As Lieutenant Colonel Suzanne Nielsen wrote in a 2010 assessment for the Army War College, “The Army attained tactical and operational excellence but failed to develop leaders well-suited to helping political leaders attain strategic success.” Effectively, the army had confused leadership of a battalion (the first level at which a commander has a staff) with generalship.

In Iraq and Afghanistan, as in Vietnam, the failure to hold generals accountable continued. “A private who loses a rifle suffers far greater consequences than a general who loses a war,” Lieutenant Colonel Paul Yingling charged in the Armed Forces Journal in 2007. True, top generals have been removed. In Vietnam, Harkins and Westmoreland were pushed out. In Iraq, General George Casey was yanked from command before he expected to leave. And in Afghanistan, President Obama fired both General David McKiernan and General Stanley McChrystal. Yet these exceptions simply prove the rule. The only ousters that occurred were decided on by civilians who had grown impatient with the conduct of the wars. Within the army’s organization, generals commanding divisions were not fired. And taking management action to replace only the top general in a war is hardly a winning approach.

Fire Away

The history related here has clear implications for business as well as military leadership. The personnel equivalent of Gresham’s Law is that bad leaders drive out good ones, and mediocrity can quickly become institutionalized. To regain its strengths in adaptability and increase its combat effectiveness, the army must restore accountability. All its generals should face rigorous review. Those whose initiative takes us closer to a shared vision of success should be promoted. Those who prove unequal to this high challenge should be moved out of the way (though perhaps given another chance when circumstances change) so that others might succeed. In the military, where incompetence gets people killed, inadequate leaders should not linger in place.

Excellent talent management is vital to any organization. As business leaders look to the U.S. military for lessons, they will find many positive ones. The army knows how to produce a well-trained, highly motivated, and extremely diverse workforce. But business should also heed the negative lesson the military teaches about leadership and strategy.

When the mission of an enterprise is clear and placed front and center, the relative performance of leaders can be assessed objectively. The decision on whether an individual deserves high rank can be, in Drucker’s term, ruthless—but yet the opposite of cruel.

READ MORE:

https://hbr.org/2012/10/what-ever-happened-to-accountability

MEANWHILE, LITTLE SHIT ZELENSKYYYYY:

PARIS (Sputnik) - The United States is tired of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and will stop supporting him as soon as Washington no longer needs "its puppet" in Kiev, Florian Philippot, leader of the French Patriots party, said on Sunday.

"The American government is starting to get tired of Zelenskyy and is asking him to negotiate with Russia! When the US no longer needs its puppet, they will get rid of him, as always!" Philippot said on Twitter.

On Saturday, a US media outlet reported citing sources that the administration of US President Joe Biden was privately asking the Ukrainian leadership to demonstrate a readiness to negotiate with Moscow.

The request is not intended to push Ukraine to the negotiating table, the sources said, but to ensure that the government in Kiev retains support from other countries that face citizens' concerns about the duration of the conflict in Ukraine.

READ MORE:

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

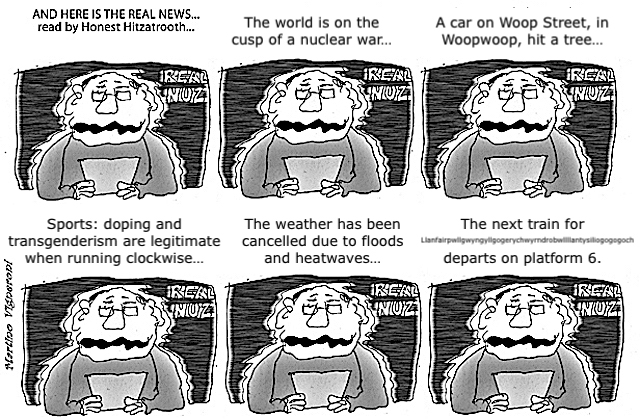

THE NAME OF THE TOWN IN THE CARTOON IS:

- By Gus Leonisky at 7 Nov 2022 - 11:10am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

3 hours 35 min ago

3 hours 43 min ago

3 hours 48 min ago

7 hours 26 min ago

11 hours 22 min ago

16 hours 9 min ago

1 day 22 min ago

1 day 6 hours ago

1 day 7 hours ago

1 day 7 hours ago