Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

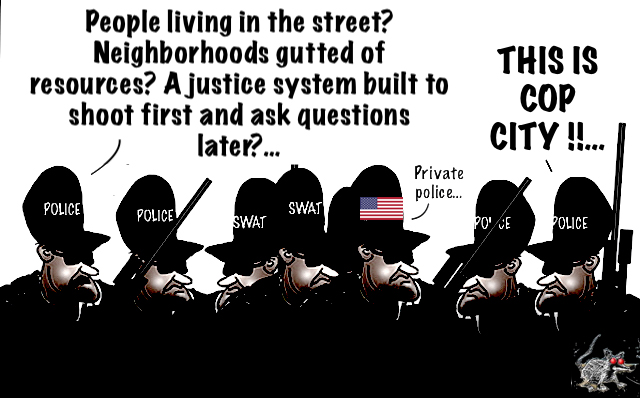

cop city......

Day by day, the ideas that define a dystopian society slyly creep their way into reality. Whether it is the constant surveillance at the hands of intelligence agencies or the abandonment of millions of people systemically left behind, the images associated with our society today can scare even the most cynical writers. One recent development grabbing headlines during the past few days is the building of a “Cop City” near the jewel of the South, Atlanta. The police killing of Tortuguita, a protester and environmental activist, is the latest transgression at the hands of the Atlanta police and its Cop City investors, but the forming of this project, with the help of financial elites, is what drew attention to the site in the first place.

Kamau Franklin, an attorney, civil rights activist and founder of Community Movement Builders, sits down with Robert Scheer in this episode of Scheer Intelligence to discuss the current state of affairs in Atlanta and specifically, Cop City. Franklin breaks down the underpinnings of a society that allows for projects like this to move forward while there are still people living in the street, neighborhoods gutted of resources and a justice system built to shoot first and ask questions later.

“Atlanta used to be a 60% Black city,” Franklin explains, but now that number has dwindled to 49%, and the rise in gentrification along with the destruction of public housing enables these kinds of stats. Despite the makeup of Atlanta’s major political institutions often having Black representation, Franklin says, “Having someone who looks like you in a place of power is never enough, particularly if that person doesn’t share ideological or other political interests with you. They are far more connected to serving a certain class of elites.”

When it comes to the creation of Cop City—and the recent unjust crackdown on protesters—Franklin reveals the insidious nature of funding and political loopholes that exist in order to make the project work. “It’s extremely important that people realize… These police foundations are taking off across the country. They’re not accountable to public officials because they are private corporations, private nonprofits. They get resources from corporations. Here, the Cop City endeavor is going to cost at least $90 million. $60 million of that has been raised through private donations through corporations. $30 million is from the city itself.”

CreditsHost:Producer:TranscriptRobert Scheer:

Hi, this is Robert Scheer with another edition of Scheer Intelligence, where the intelligence comes from my guest otherwise, this would be extremely egotistical on my part. Kamau Franklin, a lawyer by training a civil rights activist, human rights activist, originally from where I’m originally from, New York City. I think he’s from Brooklyn and I’m from the Bronx so I always… I hardly ever went there, thought they were kind of [inaudible]. But anyway, after ten years of practicing law in New York City and being very active, and I think one thing I would like to talk to you about, you were involved in the teachings of Malcolm X and so forth, which I think is very germane to where we are right now in terms of justice and civil rights, because certainly Malcolm X was opposed to something that Chris Hedges recently criticized in my own publication: the belief that representation is everything and what you end up is with, you know, the appearance of an integrated police force or in Memphis, even a dominant, predominantly Black police force. And yet, just as or maybe more destructive in terms of policing the community. So why don’t we just begin there? But you made a decision to move to Atlanta at a certain point. You’re involved with a group called the Community Movement Builders. And I’m accused, even by people who like this show, of talking too much. So why don’t you structure the conversation, what’s going on in Memphis, Atlanta, what’s going on with civil rights and what have you learned in your own journey?

Kamau Franklin:

Sure. But thanks for having me, first of all. It’s a pleasure to sit down and talk to you about the work that I do. But just to talk to you because of your history in journalism. So I really appreciate the time spent. And so I would say, you know, I’ve been an organizer since the late 1980s, like you said, originally from Brooklyn, I now live in Atlanta. For a time period, I lived in Jackson, Mississippi. And I do subscribe still to the politics of Black folks having a right to control our communities, at the institutions in our communities. But even within that, as we’ve seen over the last 40, 50, 60 years, the type of control and/or representation we have, I should say, is not really control, right? So having representation in and of itself doesn’t mean that the majority of people in any community, particularly a poor and/or working class community, have any more say over what happens in that community just because the people representing that community are now Black as opposed to whites, particularly when those folks who are their representatives in those communities are far more interested in being ideologically aligned with, but interested in being next to power right next to elites. And usually how that goes in a lot of these large cities is that you have Black electoral leadership, but you have white economic elites, and they will have an arrangement, let’s say, on how the city should be run. And that’s both, you know, the corporate elites and the developer elites, which is why under Black leadership, again, over the last 20 or 30 years in Atlanta and in other cities, or I should say, not closing it off just to Black leadership, let’s open it up to what would be considered Democratic liberal leadership right? That no matter whom is in these places as mayor or city council, all of these spaces have been gentrified, which means the working class population, the poor populations have been pushed out of these neighborhoods in these communities, one way which they’ve done that is through the police, but in other ways, too, the rising prices of living in these communities through the acts of developers and the corporations which have made these places their home. And so a lot of the things that we see is cosmetic changes that have happened over the last 50 or 60 years in this country around Black folks being mayors, now governors and even presidents really haven’t meant a lot to the Black, poor and working class population, mass population, because the priorities of these officials are not these populations. It is not about helping or supporting or giving power or bringing power to these populations. So I see a lot of cosmetic changes over the last 30 years when I’ve been organizing, and I don’t see the mere fact that we have Black faces as a victory. When those faces don’t do anything for the larger community.

Scheer:

So let me ask you, I wrote a book, They Know Everything About You and it’s about the surveillance society and modern technology. And one thing that popped up when I was a journalist, I went to Atlanta and I was in Memphis. I’ve been in these places, but it’s been decades. So I’ve been trying to brush up on what’s going on. But the point you just made resonates where I live and where I work. For many years at the Los Angeles Times, we have a yes, we have a police department that is no longer all white, and yet we have police brutality and we have very famous cases here. We have LatinX people who are contemptuous of poorer LatinX people and make remarks and we had a scandal about that. We have just replaced the district attorney who was a Black woman who was accused of and, you know, a strong opposition within the Black community to the way she was. But I want to get to this use of technology because that keeps popping up here. Predictive policing, surveillance cameras. And one of the things you are opposed to in Atlanta is this what you call, critics call “Cop City” and the taking of a part of a forest and building a whole modern military encampment of training people and I just want to question it’s presented as sort of, you know, unquestioned, good-to-use technology. But then you look at it in many of these police departments, including here in Los Angeles, you have companies like Palantir, which was started by the CIA, and they do all this data mining. And the main effect of this data mining is to do predictive policing which you say, okay, it’s this corner of that neighborhood and then you are flood it with police and it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. You find people doing what might be minor crime, but then they get jailed and they plea bargain. And you have basically the criminalization of a population that might… that wouldn’t have gone in that direction. So why are you opposed to this Cop City? That’s your real big issue. Now, tell us something about the death of somebody who was protesting, also wanting to preserve a forest area that you have. And that’s the controversy that actually got me to call you and wanted to do this interview. But I’m happy to have your broader vision.

Franklin:

So Cop City is basically an idea that came out of the mayor from Atlanta, the Atlanta Police Foundation and the Atlanta police themselves and the corporations who support it. It came out of the 2020 uprisings against police violence that were taking place all across this country. So, you know, George Floyd was killed, Breonna Taylor was killed here in Atlanta. Rayshard Brooks was killed by the police. And there were massive protests about these killings. And so these plans for Cop City, which were already being made, were suddenly introduced after the uprisings and they were introduced and these are the words of the mayor, not our words, to lift the morale of the police. And then later they added on the idea that this was going to help stop crime. So a facility that couldn’t be built even without protests for three or four years was somehow supposed to be related to stopping crime. And so we knew that not to be the case right away. But what we did see was that, based on what was being built in what’s called Cop City, well over a dozen firing ranges, militarized grade technology and equipment, a landing pad for Black Hawk helicopters, mock cities, to practice crowd control techniques and just the total buildout of this area in which 43% of those being trained or scheduled to be trained in the area will be police from across the country, not Atlanta police, not even Georgia police, but police from outside the country. In addition to the fact that the state of Georgia and the city of Atlanta in particular, already has a working relationship with Israeli police to train on tactics and methodologies of crowd control. So we saw this as basically a police developed military base. Right? One that was for the domestic police as opposed to the military, one that seemed to have two reasons, in addition to lifting the morale of the police, but also was to further over criminalize certain communities, particularly Black and brown communities, which were already being gentrified here in Atlanta. But two, was that this was also about stopping movements and stopping organizing from happening. The fact that this was whipped out post the 2020 uprisings where Atlanta itself felt it got caught off guard by the level of the uprisings that this was really about: how do we put these things back in their place? How do we make sure that the level of uprisings doesn’t happen again? You remember these uprisings around police violence. So when we heard about the plans, the ideas, the connections that were made in terms of why they wanted to do this, and when they wanted to do it, it became for us, in addition to the idea that they were going to have to rip up 90 acres of forest, they’re renting over or leasing over 300 acres to the Atlanta Police Foundation. And again, Atlanta Police Foundation is not a public entity, it is a private entity which is now going to be responsible for all the training. So in addition to ripping up 90 acres, having control over over 300 acres, we found that this was not something that anybody had asked for. Not something that anybody was in favor of. All surveys have shown, even before the city council voted to approve, that over 70% of Atlantans were not for it. And people who are adjacent to the neighborhood where it is going to be built, a working class Black neighborhood, that over 90% of those residents were not for it. So we saw it as something that we wanted to set our sights on trying to stop, and folks named it, colloquially speaking, “Cop City” and we’ve been organizing since 2021 to stop it from happening.

Scheer:

You know, the point you made about these foundations is a nationwide problem, and it’s a way of avoiding public involvement and public scrutiny, as I see it, in decisions about policing, because you can get their private money so you don’t even have to have city council meetings about the details. And so private corporations, why don’t you tell us about that? Because this is happening all over the country. And then before I forget it, I had never heard this about the… Is it an Israeli company or Israeli…

Franklin:

The Israeli police themselves have special training operations or contractual relationships with cities all over this country. But in Atlanta, they have one or I should say, in Georgia, where they work with different policing agencies. It’s actually located here in Atlanta at Georgia State University. But when they come here, they do different training with police officers here in the state of Georgia, including in Atlanta. And so I…

Scheer:

Are they using skills developed in controlling the Palestinians?

Franklin:

That’s exactly what they’re doing. They’re exchanging tactics and strategies and skills for not only crowd control, but everyday policing methods. And so I always say to people, so the same tactics and strategies that the Israeli police use against Palestinians are going to be imported here. And the same tactics and strategies used against the larger Black and brown communities are being exported to Palestine. So this is a symbiotic relationship that they have and obviously for the Israelis, it’s part of a tactic of being closer to U.S. administrations at a local level and so forth in order to protect the larger state of Israel from condemnation. So still, it means that they are exchanging tactics with each other, strategies with each other, training with each other on how to do policing. I think on your question of the corporations, it’s extremely important that people will realize that you’re right that the corporations…these police foundations are taking off across the country. They’re not accountable to public officials because they are private corporations, private nonprofits. They get resources from corporations. Here, the Cop City Endeavor is going to cost at least $90 million. $60 million of that has been raised through private donations through corporations. 30 million is from the city itself. The Atlanta Police Foundation again gets to…it’s basically their facility that they’re renting from the city of Atlanta for $10 a year, if I’m not mistaken, for the next 20 or 30 years. So, this is completely not going to be scrutinized by the public or answerable through city council hearings. They will train as they see fit, as an agency set up to promote policing. In addition, you talked about surveillance, Atlanta is the number one surveilled city and part of that surveillance, in terms of the connectivity of it, is also run by the Atlanta Police Foundation, which has put money forth to try to connect the public cameras to each other, to be a new tool for law enforcement. So I’m not sure who elected or decided that the Police Foundation should play a prominent role in, quote unquote, crime fighting and or quote unquote, training of the police that they’re not elected to do so. The same corporations that claimed that they were desirable or protecting Black lives during the 2020 uprisings are the same corporations that now are giving to the Atlanta Police Foundation to build this Cop City.

Scheer:

Can you name some of these companies?

Franklin:

Sure. There’s everything from Coca-Cola to UPS, Delta, some of the corporations, some of the institutions that are connected to it are Georgia State through fundraising. There’s institutions like Spelman and Morehouse, Georgia Tech. There’s all of these corporations, every big corporation, national corporation that we know of, like over 80 of them have at some point donated to the idea of building this Cop City.

Scheer:

You know, you’re talking about the jewel of the South, Atlanta, right? You’re talking about but not just of, you know, oppressive, racist, slave owning South. But when there was the movements for change, after all, this is where Martin Luther King came out, the Julian Bond, John Lewis, who died a few years back. I mean, I knew John Lewis and Julian Bond very, I was very close to them and I actually participated in some civil rights activities very early on, but knew them. And it’s just appalling to think that Atlanta would now be an example of gentrification oppressing ordinary Black people as well as ordinary white people looking for [inaudible] and what happened here, it’s startling. You know, where is social conscience?

Franklin:

We have to remember that even though Atlanta sometimes is considered either a creator of the civil rights movement or important figures of the civil rights movement came from Atlanta. The civil rights movement in a lot of ways bypassed Atlanta. Most of the activity of the organizing took place in other places because there was already an agreement between the, at the time, the white political elite and economic elite and what would be considered at the time the Black leadership, reverends, ministers, so forth and so on about how things would happen here in Atlanta to avoid a large scale civil rights movement in the scenes of a Bull Connor type activity happening against a larger and growing Black population. And so over time, you know, as the Black population in Atlanta continually increased and it became obvious a little bit post-Jim Crow a little bit pre-Jim Crow should say pre-ending of Jim Crow that there would be a majority Black city here. And then it became a political Black elite that made deals with a white economic elite around how Atlanta would be run. And so some of those same civil rights icons, i.e., Andy Young, I bring out in particular, you know, participated completely in the beginnings of the gentrification process in Atlanta, the knocking down of all public housing, the destruction of all public housing in Atlanta, the paying of homeless people to move out of Atlanta. And all of this was done to make room for the Olympics, to make Atlanta a showcase. Since that time, Atlanta used to be a 60% Black city. Today, Atlanta is now a 49% Black city, and is no longer majority Black. And this was done, and again, the destruction of public housing, the gentrification has taken place. This has all been done under Black mayor leadership, mayoral leadership and Black majority city councils for the most part. This has been why, you’re right, representation politics is never enough. Having someone who looks like you in a place of power is never enough, particularly that person doesn’t share either ideological or other political interests with you. They have far more connected to serving a certain class of elites. And that’s exactly what’s here in Atlanta. Again, from, let’s say, even Maynard Jackson, his second term. His first term, he did a lot to shake things up. And then I think the economic elite tried to put him in his place. But mayor after mayor after mayor since that time period have basically allowed the city to be a corporate playground, where now they’ve pushed out the vast majority of Black people and they’ve pushed out poor working class people. And the strata now are great, where Atlanta has the greatest income inequality gap of any major city in the country.

Scheer:

So let’s just focus on that a little bit, because that, of course, is where policing gets its edge and where they yes, sometimes they are forced to make mistakes because they think they’re going by skin color and they actually end up arresting people who can be represented later or come from a more affluent section. But the fact of the matter is, it’s a way of, I mean, if you look at the incarcerated population in America, you know, are we talking about really the betrayal, let’s take a figure. I was surprised reading about your activities, you know, yes, you identified with Malcolm X as do many people. And even though I’m white, I certainly think Malcolm X was a great leader. But you also talked about the spirit of Martin Luther King and particularly in those last years and it’s ironic. Here was Martin Luther King killed while trying to bring consciousness about class to Memphis. Why was he supporting a garbage workers strike? Why was he doing a war on poverty? And we’ve had the destruction of Martin Luther King’s legacy really, his commitment, you know, And now he’s been made into a, you know, benign statue. You can talk about “I have a Dream,” but really, he saw very clearly and I think John Lewis and Julian Bond, at least when I knew them, saw that, that if you didn’t get into the economics and yes, because of segregation and legacy and racism, you know, people, brown and Black people are going to be hit hardest. And they have they were in the banking meltdown and everything else. But the fact of the matter is, you can buy off part of any population. And that’s really what your work is all about, is educating about this, isn’t it?

Franklin:

Yeah, I mean, I would say we always keep, like our organization, Community Movement Builders, we always keep a race and class analysis to the work that we do. So for us, there’s no distinction or no separation between analyzing the issues, particularly that Black people face here and at other working class and poor people face here outside of both a race and class analysis. Because you’re exactly correct that any group can be, any part of any group can be bought off. And it’s basically the model that’s been taken on since the 1960s and seventies, right? What happened to the radical movements of the sixties and seventies particularly, we can say the Black power movement, the Weather Underground or other aspects like the white radical movements. All of those movements were basically destroyed in the sixties and seventies by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, in other words, the United States federal government by local entities, local governmental entities that teamed up in a task force with those groups. Those groups were destroyed through everything from breaking up their organizations through infiltration, through murder, through jailings and prisons. They were destroyed. And what was left standing was a civil rights class who only believed or who mainly believed that if we vote, basically voting for Democrats, that somehow we could win our liberation and or freedom. Well this tied people to a liberal Democratic establishment which did not have an interest in overturning class relations right? But had an interest in sort of maintaining a status quo that was not as oppressive as is their right wing counterparts, but still oppressive to a degree. So for us, in terms of our estimation, the idea that liberal Democrats, whether they be Black, white or brown or anybody else, somehow are paving the way for freedom or liberation is a ridiculous notion. They have just as much interest in maintaining the systems of how capitalism works, in maintaining the gross inequities of how wealth is filtered to the top as their Republican counterparts. They’re just, they could be a little smoother about it. They have their different ways of doing it, but it doesn’t mean that they are ideologically opposed to how the system works in and of itself. And so we don’t separate a race analysis of how things work from a class analysis because corporations, government elites can always allow a certain percentage of someone who does not look like them to be a part of it for them to get rewards as long as they continue to keep control over the larger apparatus of how power works and is distributed in the world.

Scheer:

And this all gets back to policing and the law. You were a lawyer for ten years and I gathered in Brooklyn and dealt with a lot of these cases. James Forman Jr., son of a major civil rights figure, is now a professor at Yale. I interviewed him for this show and he wrote a very interesting book about his own time as a public defender in Washington and so forth. And when you look at the statistics of the incarcerated population in America, you look at the plea bargaining in 90, what, 94% of the cases, you know, we’re going to get you on something so go for this one. And next thing you know, you’re on this road to invisibility, incarceration. You know, relate your earlier experience as a lawyer to what you’re doing now. And I want one little footnote because I forget it or we run out of time. I mentioned to you before we started, when I was in Atlanta and I wrote a pretty controversial… I was going to a lot of American cities, a number of American cities when it started with Jimmy Carter’s, you know, trying to do something about poverty, he claimed and so forth. When I went to Atlanta and I actually went to a place, you mentioned public housing, Perry Homes and people don’t even, I don’t even know if it exists now. But I pointed out to John Lewis and Julian Bond, I said to these guys, you know, I just was over there. I’m a white guy, but I was over there at Perry Homes, and that’s a different Atlanta, you know, and they said, Well, yeah. Perry Holmes. But, you know, I said, Let’s go. And I took each one of them there. They were running against each other, Congress, and they were appalled. I said, Well, you know, come on, you guys did… Everybody’s building up Atlanta, you know, how great it is, you know, the New South and all that. And I said, what is this? You know, these are the people that have, you know, not only just forgotten, you know, that you want to… People want to get out of town. So let me ask you about the law, because that’s really why we’re here and the incarceration rate and that’s really what, where it all happens, right?

Franklin:

Yeah. And, you know, as somebody who grew up in public housing in Brooklyn, right, So I grew up in what was called Albany Projects in Brooklyn. So, you know, being a lawyer, you know, I was already very politicized when I became a lawyer. But when I started practicing criminal law and you got to see how the wheels turned or how the sausage is made. It confirmed everything that you knew from the outside, obviously, that anybody who’d been arrested also knows, is that the majority of people in these major cities who are targeted for arrest are Black people, particularly young Black people. And so being a practicing attorney and seeing how the system worked, everything from who is targeted for arrest to how police reports are written and the bias or the first step, let’s say, in a process that includes lying by the police as to what happened, how it happened, what their reactions were, starts usually with the police report. From there going to trial or to court, where you have judges who instantly believe or are far more prone to believe the police version of events than they are the defendant. And that has to do with everything from how bail is set. It has everything to do with the demeanor of the judge doing a trial if it goes to a trial. It comes as anything to do with the type of pressure that’s put on defense attorneys to even plea bargain. So those things are baked into the cake of how the court system and policing works. And then finally, all over the country, the stats are very similar. Over 90% of all criminal cases end in plea bargaining. And so it’s not even about whether or not people are innocent before they’re proven guilty. What usually happens is after an arrest, you’re kind of considered guilty and you have to work your way out of that system right? And sometimes the easiest way for people to work their way out of the system so they can get back to a job or get back to their normal life is to take a plea. But taking a plea means that it’s time served or means you have a record which impacts you in other ways, in loans and where you can live, what kind of jobs you can get. All these things are interconnected in terms of helping to keep a certain oppressed and/or impoverished population within the United States. And even though it disproportionately impacts and affects Black people and brown people, obviously there’s still impacts upon sort of working class and poor white folks also in certain areas. But any place there is a relatively speaking, large amount of a Black population, it is that population that suffers. Here in Atlanta, 90% of the arrests in Fulton County to the county that Atlanta is located in are of Black people, even though, as I stated, the city itself is less than 50% Black at this particular stage.

Scheer:

Wait a minute 90% of arrests?

Franklin:

90% of the arrests. In fact, Fulton County is now, they just asked Atlanta to keep open its jail, which it had also promised to close. And so it’s keeping open its jail and renting it to the county to add approximately 700 more beds or 700 more jail cells. In addition to that, it was just announced that the same Fulton County wants to build a brand new jail that’s going to cost $2 billion. And so we link together the activities of Cop City, the activities of arrests that are already happening, the activities of the jail population, and the increased spending on the jail population. It’s all about the gentrification of the city of Atlanta, the northern part of Atlanta, Buckhead, as you mentioned earlier in sort of our pre-interview, as the sort of the deciders of what happens in greater Atlanta, because they’re considered the economic engine and everybody else has to bend to their will. This is what the, again, the Black elected politicians have done in terms of serving the interests of the elites. It means oppressing and jailing, harassing, exploiting the larger Black population in Atlanta.

Scheer:

You know, I think this notion of gentrification, by the way, I teach at the University of Southern California, which is in a once Black neighborhood and brown neighborhood and so forth, and we have gates around the campus and we have built a gated village right in the middle of our campus. So gentrification is a menace because it’s basically apartheid it’s basically walling off people. And we also have this massive homeless population. I don’t want to once again be accused of picking on Atlanta, as I was by the Atlanta Journal. This is a big problem where we live here, right where I’m living in Los Angeles. And with 55,000 homeless people and car encampments here of all races, but more Black and brown than white. And I want to nail this because it’s a conceit of our progressive politicians. And I remember and I’m not being disrespectful, in the memory of John Lewis and Julian Bond, but I also remember going with them to Buckhead and talking about white privilege and then that you could ignore Perry Homes and so forth. And it wasn’t their fault, it was the way politics were always who’s going to vote? Where is the money coming from? You mentioned Coca Cola. They both had to compete somehow to get approval. I forget his name, the head of what started with a W, I think a famous guy was head of Coca-Cola. They had to, you had to be you know, that’s what Andy Young was so good at. I had a lot of respect for Andy Young, but he was particularly effective with white liberals and money corporations. And he was so important to the whole Carter phenomena. And, you know, and you have this, and I want to connect that with the development of this underclass, which is more Black than anything else, and connect that to surveillance. Because if all you know about people is what you capture on, and you’ve mentioned Atlanta is the most surveilled city. We’re really talking about modern policing and I think that’s what Cop City is dedicated to, the most modern technology. You’re talking about being able to define a person. This is what totalitarian governments do. They can define a people through surveillance, through modern technology. And, you know, when, after all, you know, Israel, what they do to the Palestinians who are in the occupied areas, that’s an occupied power, that they can’t deny that there is a population they also surveil within their own. But here we’re talking about people who are citizens, their voters and so forth. And basically and it’s not just Atlanta, let me be clear. It’s here in Los Angeles, it’s everywhere I’ve looked. Surveillance allows you to define a population. Okay. There are those young guys, they’re going to do something. And that’s what we see with these cases. He was walking the wrong way. They said the wrong thing. He was robbing something and you built a case. And what you just said before, I think, given that this is Black History Month, is really the most alarming thing that, what you say 90% of…?

Franklin:

90% of the arrests in Fulton County are of Black people.

Scheer:

Well, so some racist is going to say, yeah, they’re by design criminals. But the system is designed, is set up to…

Franklin:

To target them.

Scheer:

Yeah, first of all, if you had cameras all the time in the boardrooms of American corporations, in the bathrooms of American Corp, big corporate elites, you’d find a lot of crime, you’d find a lot of crime that would put people away, hopefully would put them away for much longer. After all, the whole housing meltdown, which robbed Black, educated college graduates of 70% of their wealth, according to the Federal Reserve and brown people of 60%. The whole housing debacle that was designed in Wall Street, none of them went to jail. So predictive policing says we know these Black people, brown people are criminals. We’re going to get the evidence now. We’re going to put up a lot of cameras. Could you please describe the surveillance that goes on in the jewel of the South, Atlanta?

Franklin:

Yeah, I mean, the surveillance is omnipresent because not only is it public surveillance in terms of public cameras on buildings or police cameras, but there’s a hooking up of the system of private doors. And so, you know, the little door ringers that we have, folks all have now with the cameras. All of those can be hooked up to a centralized database of the police. And so basically a tracking of individuals can be done from the moment they leave their house, obviously, through red lights and green lights and everything else they do to probably when they come back home. And so although I think that surveillance is omnipresent and insidious, it starts off really with the criminalization which is taking place pre the technology that we have here. The reason that these communities are watched is because of the racism and criminalization of certain communities, right? And so, therefore, that is where you look for people to arrest. And like you said, for almost any reason, like it’s many stats that have shown that, you know, particularly during the height of the nineties and 2000s, that when weed was completely legal, that white folks and Black folks smoked weed almost at the same rate right? If not whites being a little higher. But the arrest for using weed or having weed or or selling weed was always predominantly within the Black community. So this is not about a situation where people are more prone to some sort of crime. This is a situation where certain populations are targeted to be criminalized, and then every other reason for why they need to be followed or searched or looked at begins to make sense, particularly from the eyes of those who are doing that work, right? And we should also state the eyes of the corporate media, which repeats or builds out this narrative that all of this crime is taking place. I lastly say on something like this that the safest communities in the United States are not the communities that are overpoliced. It is the communities who have resources that they can spend resources on community centers or on their schools or after school activities. Those are the neighborhoods that are most safest. So to save $30 million that the city of Atlanta is giving, to build this idea of this cop city, this basic, basic military complex, can be used for affordable housing. It could be used for helping make sure that there are afterschool programs. It could be used for better schools. So it can be used to improve the environment of the very people who are suffering from lack of resources instead of having the only resource that’s poured into that community is more frontline cops who will be surveilling, chasing down, targeting, harassing and arresting, particularly young Black people in these communities.

Scheer [00:38:57] Yeah, and if you look at these cases where we, because of video cameras that people have, we now see, okay, somebody stole a soda or they were acting improperly or violently even in some convenience store or they, you know, on a street selling cigarettes in Brooklyn or something and misbehave. And it’s all this, you know, it starts with a lot of petty crime, alienated people, desperate and so forth. And in a community somewhat in disarray and certainly neglected, if you put those cameras, as I say, I wasn’t joking before about in corporate boardrooms where the real mischief is done, where the deals are made. You know, and you did predictive policing there because we know there’s been an awful lot of corporate crime that has really hurt the world. Okay. So if you want to predict where it’s going to happen, you should do that. You would have your FBI and your state agencies and everything, right, going after, you know, corporate boardrooms and so forth and all. Let’s see. But we don’t do that. We don’t even use the IRS to go after their accounts. We mostly audit poor people, lower middle class people. But I want it to end this way. Talk a little bit about your own background. How did you get from the project in Brooklyn to where you are now and what’s your journey?

Franklin:

Well, I mean, my journey is one of being born and raised in Brooklyn, me and my sister. My mother is from Charleston, South Carolina, and she actually grew up during Jim Crow times. And my mother would relate stories to us about her life living under Jim Crow. In fact, my mother, who passed away last year, had a scar on her back from the data she died from when she was one of several of her friends on a whites only playground and a cop chased them up. My mother wasn’t as fast as she got hit in the back with a bully club which left a scar on her back until the day that she died. And so hearing stories like that, my mother, who grew up during the civil rights movement, relayed stories, it got somebody like me interested in, you know, how the world works or what was the journey of my mother and others from South Carolina to New York, coming up to a place like New York for a job. Winding up on welfare and, you know, I was living in the projects. Why did our neighborhoods not have…

Scheer:

What neighborhood were you in?

Franklin:

We were in Crown Heights, Bed-Stuy area.

Scheer:

Oh, yeah. Yeah. So I went there with Bobby Kennedy when he was the senator and there was supposed to be a big project to help Bed-Stuy. Did that ever work out?

Franklin:

No. No. The only thing it’s the only change in Bed-Stuy from that time, at least what I’ve been there has been, again, gentrification. That’s been the biggest change in Bed-Stuy and Crown Heights is that, again, except for a few neighborhoods in Brooklyn, most of the urban areas that I grew up in, which were, again, working class and poor but livable areas and neighborhoods where people, you know, have had some lives. And if they had more resources, they’d have more opportunities and chances. You know, those folks have been pushed out and moved out of their communities and neighborhoods. And again, Atlanta is not alone, as you said, this is a phenomenon happening all across the country where basically the motto is a French model of what the urban area should look like. The urban area is for the elites, the whites and those of color around in the periphery of the urban area. And that’s now the model that’s happening here in the United States. So we essentially in some ways have sundown towns now in places like Atlanta, in New York. But they’re not strictly based on race, but they’re based on economics, right? Who can’t afford to live in central cities anymore but you still used to have to come here to work, but after a certain time period, you have to go.

Scheer:

So how did you go from the project to being a lawyer?

Franklin:

I mean, for me, it just got politicized in my twenties.

Scheer:

What years were that, I didn’t even ask you.

Franklin:

I was politicized in the middle mid to late eighties, ’86, ’87, ’88.

Scheer:

So when were you born?

Franklin:

I was born in 1967. I’m 55 years old.

Scheer:

Okay. So when Jimmy Carter went up to Charlotte Street and in the Bronx and talked about ending poverty, that was the 1980s. So what were you? You were…

Franklin:

I was 13 years old.

Scheer:

13? Yeah. And then they were certainly going to end it in Brooklyn as well as the Bronx and all that. They ended it by gentrification, Brooklyn…

Franklin:

I do remember it, in one of my earliest memories of how I know what year…

Scheer:

I’m only bringing it up because I was there and..

Franklin:

I was, quickly, one of the only reasons I remember Jimmy Carter as a young person was because it was one of the first fliers I remember having when we were in Albany Projects that my mother had was something either you know, either something in the mail or whatever. And so, yeah, so I obviously, you know, I don’t have a huge memories of that time period, but. But yeah, but that’s around the time period that we moved to Albany Projects from another area of Brooklyn that we lived in.

Scheer:

Yeah. So when you went to school there and…

Franklin:

Yeah. So when I got politicized, I wasn’t going to go to college.

Scheer:

But where did you go to high school?

Franklin:

George Westinghouse High School, which was downtown Brooklyn. And after high school, a friend of a friend of mine and I decided we were going to go to college. We were just going to get regular jobs.

Scheer:

And is that near Tilden High School.

Franklin:

Yeah, Tilden is not that far.

Scheer:

Yeah, I remember that neighborhood.

Franklin:

So a friend and I, a good friend of mine, decided we weren’t going to go to college. We’re going to get real jobs, be men and then over the summertime of my graduating year, I found out that he was actually killed. And that kind of was what led me, one of the things that led me to decide to go to college. So I went to Baruch College in Manhattan. Then I went to Brooklyn…

Scheer:

City College, Baruch College.

Franklin:

Baruch College as part of CUNY. Yeah, so in Manhattan.

Scheer:

Yeah.

Franklin:

Yeah. And then I went to Brooklyn College for my Masters, and then I went to Fordham Law School. Most of this time I still lived in the projects because my mom was sick. And she needed support in terms of being taken care of.

Scheer:

Yeah.

Franklin:

So I kept it quiet that I was a lawyer in the projects for a little while.

Scheer:

Yeah. And then you went up to the Bronx, to Fordham to get educated?

Franklin:

Well, for a while school was actually in the city. Yeah, at Lincoln Square, at Lincoln Center.

Scheer:

Okay. So how did, why didn’t you sell out?

Franklin:

I was too politicized, but to my mother’s disappointment, I was too politicized by that time period. I think she was hoping that with all these degrees and stuff like that, that I would probably make a little bit more money than I did in my life. But I was already really politicized around what the system was. And so for me, joining the system was not really an option. Or getting a corporate job was not really an option because I felt I would suffocate under that kind of life or whatever, which hasn’t helped me a lot in terms of my student loans. But, you know, it’s been sort of a life well-lead for me in terms of doing something that I thought was important or think is important in terms of grassroots organizing, working with and for my community here.

Scheer:

And it was going to run in the middle of Black History Month. I’m interested in that journey. I mean, did you get any idealism out of Fordham Law School? Did you? I mean, after all, the pope had talked a lot of at least Pope John back in the sixties and current pope about poverty. There was supposed to be a Catholic conscience, didn’t come up in law school at all?

Franklin:

I think Jesuit, I think Fordham is a Jesuit school. But I think again, by the time I’d enter law school, for me, it was all about evaluating what these institutions were. And so for me, these were you know, Fordham was a relatively speaking, New York centered, elite institution that was meant to make you feel good about the fact you were getting this degree so that you could be next to judges and other lawyers and other people of prominence. I mean, if anything, it was sort of setting you up to be part of a bourgeois class or a middle class of professionals. And I think at that particular time, because I was.

Scheer:

I call it the courtier class, to serve the Court. Yes, I’m actually trying to write a book about it right now because I see that’s really what the meritocracy has come down to, you know, and you should be a Citicorp or some big bank and you, because of… you were supposed to forget the projects.

Franklin:

Yeah. Move away or do something else. I mean and I think that’s you know, with students these days too, we were just talking about the Stop Cop City movement and trying to get students involved. And we recently now have had a lot of students get more involved. But part of it is sort of a lack of a larger student movement across the country. Students have been pushed towards corporate jobs or higher, since they have so much debt that they have to pay off debt. And they’ve been pushed to believe that making money is everything in life. And so the idea of exploring politics, philosophy, ideas, how society works is something that people are told is useless as opposed to something that they should be exploring. And obviously, I think the reason they’re told it’s useless is so that they won’t interfere with what the managers are telling them that they should be doing, right?

Scheer:

Yeah, but it’s worse than that because we’re also telling people that if you care about the people who aren’t making it, who didn’t get into Fordham and so forth, then you’re with the losers and you’re in fact enabling them. It’s a very dangerous game that is played. So then you’re called upon to betray… I know I grew up I mean, I can’t deny I’m white, but I did grow up in a pretty poor area and in the Bronx and my parents were garment workers and everything. And that was always the message even back then, if you’re smart enough, you’re going to get out of here. You’re going to, you know, you’re not going to be like everybody else. And, you know…

Franklin:

Then if you do anything to help them, it’s you who gives back. That’s how you help. Yeah. You give back some dollars and then you’ve fulfilled your purpose and that’s all you should care about, right?

Scheer:

Yeah. Well, you have the same rhetoric and you and yeah, that’s why this. I don’t want to make this the whole subject here. But this representational issue is obviously very controversial. And whether we’re talking about, but any group that was marginalized and exploited gay people or anything. Yes, there’s been a lot of progress in certain areas and everything but the real issue is, does it lift the old idea, lifting everyone and giving them real opportunity? And I don’t know. I mean, it sounds like you got a good quality education, does the City College… I went to City also up in Harlem, actually, and we thought we got the best education in the world. And we were, but that was the time when Jewish kids particularly were discriminated against going to Harvard or someplace, you know, and the application. But now I really wonder if a lot of kids going even to community colleges here in California to state colleges. Is it just maybe another trap? Yeah, You know, they’ll pluck one or two out of here and you’ll go somewhere else. But mainly, like you say, you’ll end up even in a public institution with debt, you know, and, you know, and you’re kind of caught in the middle right? You could easily be part of the Atlanta elite, couldn’t you?

Franklin:

I could easily have been.

Scheer:

And even now it’s not too late. You sell out a little bit, right? I mean, isn’t that what we basically teach? And then they even have a philosophy and are just kind of altruists… In Silicon Valley, they have this idea: you got to get a lot of money however you get it, and then you give back somehow and smart philanthropy, you know, Bill Gates kind of foundation. Are you under that temptation now? I mean, we’re going longer than I expected, but I find this an interesting conversation, if you’ve got a few more minutes.

Franklin:

Yeah, I don’t feel like I’m under the temptation to do it, but I do think there are a lot more temptations than there ever have been, even in the area of work that I do, community organizing. And so it’s, you know, how representation, politics and all of this comes together is that, you know, we had a few years ago what we consider like the Black Lives Matter movement or moment. And what we could see was, again, how the representation of folks who were Black women or queer women was like, Oh, they should be projected sort of at the front of a particular movement. And also at the same time, we can potentially use these organizations again, at least the liberal elite part of it, to help us with our voting strategies in sort of the Democratic Party. And so there’s more money in organizing than it’s ever been before in its history for folks to do different kinds of work. But the question becomes, is this money well spent in making changes in the neighborhoods and communities that we all consider ourselves connected to or part of or interested in supporting? But I think the idea of representation politics, where you get lifted up because of what you are as opposed to what you think necessarily has done some damage. And again, like you said, like it’s not like it’s a terrible thing, right? That we should have a diversity of folks who are doing different things if things are working correctly. But the idea that you’re lifting certain folks up because of what they are as opposed to who they are, in addition to the fact that you’re giving people literally millions of dollars supposedly to organize in communities, but they also get a little bit like, you know, bigger salaries, the more expensive clothes they get to go on college speaking tour circuits. They get to spend the money on different things more than they ever have.

Scheer:

So, you know, it’s interesting. It’s nice, I could talk to a younger person. It seems to me the great thing that happened in the sixties was that when you were born there was actually a notion you’re not, you shouldn’t sell out. You had to find some integrity. Maybe it was a reaction to the movies of the forties and fifties being so cloying and dumb, but somehow you can contribute, attribute some of it to the artists who raised these issues. But there was an idea that life had to have certain integrity and not selling out was a big thing. Now selling out is the way to be enlightened and progressive because you’ll get to be a senator, you’ll get to be someone, you’ll be on a board, and then you’ll be able to do a lot for people. And I suspect in the issue that you’re dealing with now, Cop City, because I hear this all the time, they say, you know, I eat at a restaurant here in downtown L.A. You know, it was supposed to be a community center, but there are a lot of cops there every night. It’s very good food, a collection of restaurants, Mercado Palermo, a very good place. And however they’re going out and doing the work of basically predictive policing and defining these neighborhoods this way and so forth. And yet they themselves are kind of a success story and that is progress. Yes, because this should not be discrimination. So I think this is kind of a moment and you’re right there in Atlanta, where for the Democratic Party elite capturing the New South, having Georgia have progressive Black senators is, in fact, I can’t I won’t deny it. It’s a big victory, a very big victory against this.

Franklin:

But it’s a victory for the Democratic Party. Yes, but not necessarily a victory…

Scheer:

Historically, because we’re in Black History Month, you know. Yes, compared to slavery, compared to illegal segregation.

Franklin:

For the Democratic Party with their victory for poor working class people, particularly poor, working class.

Scheer:

I’m going to cut this off in an hour. You got 4 minutes to give me that speech. Let’s say we bring you in. You’re the commencement speaker warning us, what’s the road?

Franklin:

Well, I mean, I think the road is if we’re going to be for those of us who are organizers, for those of us who believe in making systemic or systematic changes, we have to be rooted to communities and to people’s, that rooting of those of being with those people is about for some of us, it’s going to be a mixture of race and class, but some of it’s going to be about class. But we cannot define our interests by the elite class. We can’t let folks who are billionaires or who are supporting billionaires or who are supporting an uneven distribution of wealth, be our leaders. Right? We can’t understand society through the lens of folks who are the owners of society. We have to understand our roles in society through those who are oppressed through the society. And so even when it comes to an idea around policing and police, the question is never whether it’s about the police, one police person is a good person or a bad person. Someone treats their siblings or their significant others well. Somebody takes their dog out for a good walk. I don’t care about any of that stuff, right? It’s the system of policing that is meant to control and harass and arrest certain communities. And it is also, we didn’t get into this, but it’s also meant to attack certain political ideas far more than others. Every indication or every statistic shows that most of them say that the mass shootings that happen in the United States take place by either white folks with a right wing ideology, not exclusively, but a lot of that’s what’s happening. Those are not the people who are targeted for arrest through policing agencies, whether a city level, state level or federal level. It is left folks who are targeted still to this day and bringing it back to the Cop City issue, we’ve had 19 people who’ve been arrested and charged with state domestic terrorism charges because for the most part, particularly those arrested in the force, they were arrested for sitting in trees or having campsites doing civil disobedience and direct actions. The same things that a John Lewis was doing. But those folks who were arrested, not charged with trespassing, but charged with domestic terrorism, and we didn’t get to talk about this. I forgot. I didn’t get to bring it up. I forgot to bring it up.

Scheer:

Well, take the time. Look, come on. I don’t know how many people we reach, but we could take as much time as we want.

Franklin:

I wanted to bring up… Because you asked me about it earlier. The young organizer who was killed in the forest, was killed.

Scheer:

Could you maybe use his name, too? I mean.

Franklin:

Oh, Manuel “Tortuguita” Terán I think is his… I’m messing up his last name. Terán, I think it is. But Tortuguita, who was killed by a collective, a policing agency. The Atlanta Police, DeKalb County Police, the Georgia State Troopers, Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

Scheer:

Let me just so people can look this up. Manuel Tortuguita…

Franklin:

Tortuguita.

Scheer:

Terán. They should look up this case because this goes to the destruction of idealism. This is somebody who is trying to preserve, right? An area of forest. So, you know, tell us more.

Franklin:

So that a task force of the Atlanta Police Department, DeKalb County Police Department, the state Georgia Bureau of Investigation, state troopers, the Federal Bureau of Investigations, which means the Justice Department and Homeland Security were all involved in a task force to criminalize organizers against Cop City. That has now reached a point where they did raids in force. 19 folks were arrested and charged with domestic terrorism. 14 or 15 of those in a forest, five or six of those at a protest downtown Atlanta later.

Scheer:

You should explain that there is actually the remnant of a forest in Atlanta.

Franklin:

Atlanta is considered, you know, is the city that has the biggest forest canopy of any major city in the country. So there’s major forests located in what we’ve dubbed as Weelaunee Forest, where Cop City is scheduled to be built, that they want to cut down 90 acres for this police, this militarized police center. And there’s another hundred acres or so that’s going to be cut down for a movie studio. And we should say that they’re renting to the Atlanta Police Foundation over 300 acres. And there’s nothing in the lease that prevents them from cutting down more acreage. So the fact that people are protesting and arrests have happened since the very beginning of these protests. But the fact that now protesters are being charged with domestic terrorism and accumulated in the killing of Tortuguita. So the killing of Tortuguita by all of these different agencies, and they put out the narrative that Tortuguita shot a single shot at them.

Scheer:

Look, we’ve taken a long time, tell us the whole thing, what happened.

Franklin:

The question becomes is that we don’t really know what happened. .

Scheer:

No police video camera footage?

Franklin:

Exactly. We know the version of events that the police have told us through their press releases and through their leaking of information right? They’ve not turned over all pieces of information to the family, to the family’s lawyers, and nor have they released all pieces of information to the larger public. What they’ve done is dripped information that has supported their narrative. And so apparently Tortuguita did have a gun and he may have fired a bullet, but we don’t know the circumstances in which it happened because all we’ve heard… From the evidence we’ve been able to see and gather even from the videotape that now has been released, but shockingly is not body camera images from the police themselves who were surrounding him. They claim they have no video footage whatsoever of the actual shooting of Tortuguita, but yet other police in the area have videotape, body camera imagery that they’re now releasing in which you can hear a sudden burst of gunfire, 30, 40 bullets all at once, not one shot, a slight pause and then a barrage of bullets being fired in response, but just strictly a barrage of bullets that the young person got off one shot is the story and hit an officer and then they returned fire. But yet all of these agencies, the Atlanta Police Department, are required to have body cameras on and to have them turned on when they interact in the public. We don’t have any body camera imagery whatsoever. We just recently learned that he was shot approximately 12 to 13 times. And it’s approximate because they can’t tell if he could have been shot more at this particular stage through the autopsy that was given, but at least 13 times by shotguns and handguns. We are expected to believe that this person sitting in the force by themselves at the time decided to shoot on the police officers, right? One shot, knowing that he was surrounded. And according to police, they called for him to come out of his tent that he was in. So this would be basically he shot one shot at a dozen or so police officers basically sealing his death. So we don’t believe that narrative on its face. We believe that’s a false narrative, a lie. And what gives us indication, of course, is that all the other stories of police violence that have happened over the last decade or so continually unravel once we do have information through videotape or through body camera images lately that show the police activities as opposed to what they tell the public is what’s happening to either their police reports or through their press releases, which distort a lie and tell tales about how the police arrested or handled somebody.

Scheer:

Well, it’s a case that we need to follow and I’ll get back to you on that. And then, you know, we’ve run out of time, but it’s really a fascinating conversation. And we’ll post more material on it. And I want to thank you for doing this. I want to thank Laura Kondourajian and Christopher Ho at KCRW, the NPR station in Santa Monica for posting these shows. I want to thank Joshua Scheer for being our executive producer. And the JKW Foundation for putting up some money in the memory of Jean Stein, who actually was very involved in the civil rights movement. And see you next week with another edition of Scheer Intelligence.

READ MORE:

https://scheerpost.com/2023/02/08/the-birthplace-of-american-dystopia/

- By Gus Leonisky at 11 Feb 2023 - 5:45am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

1 hour 9 min ago

1 hour 19 min ago

1 hour 31 min ago

2 hours 30 min ago

3 hours 20 min ago

4 hours 42 min ago

6 hours 25 min ago

7 hours 2 min ago

9 hours 4 min ago

11 hours 3 min ago