Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

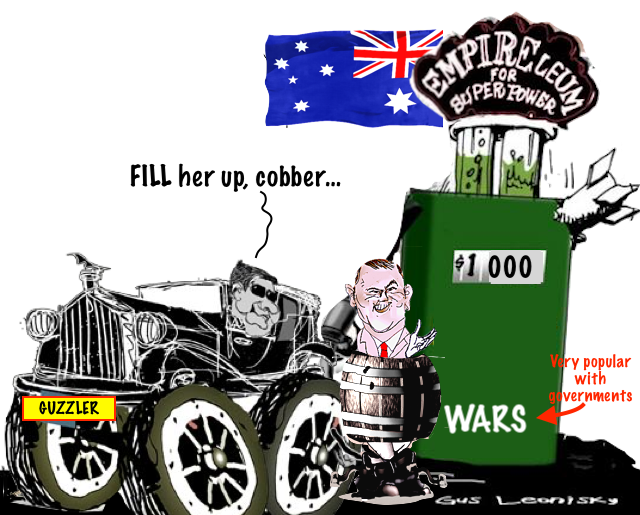

will the government save us in a fuel security emergency?........

Will the government save us in a fuel security emergency? After a long FOI fight, the Federal Government’s plan has been made public, and it’s not comforting. Rex Patrick reports.

After a year-long $150K Freedom of Information (FOI) fight to keep secret their plans for dealing with a fuel security emergency, the Australian Government has been forced to come clean and hand them over. Should we be reassured or alarmed?

There’s no single fuel emergency scenario. Australian Governments rightly ‘wargame’ all sorts of possibilities to see how they, the Australian economy and people might cope with a major disruption of liquid fuel supplies. Australia still predominantly runs on petroleum products, without which our nation would come to a crashing halt.

State-based fuel emergencyIf the pipeline between the Gore Bay Marine Terminal, west of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, and the storage tanks at Clyde near Parramatta that feed the nearby road tanker loading facilities were to fail, there would be fuel disruption across the greater Sydney metropolitan area and the State.

This would be an emergency that would engage the NSW Minister for Energy, who has extensive powers under the Energy and Utilities Administrative Act (NSW), and the NSW Department of Planning and Environment, keepers of the Petroleum Supply Disruption Response Plan. The Commonwealth Government might keep a watching brief on the State’s response, and offer assistance where required, but would not formally get involved.

Each State and Territory has their own fuel security legislation and response plans.

National fuel emergencyOnly if there was a pending or actual nationwide shortage would the Federal Government step up and take charge.

A range of scenarios exist, mostly external, that could cause a national issue. A scenario in the 2019 Fuel Security emergency report the Government wanted kept from us gave a plausible scenario: a developing conflict in the Middle East where ships were being attacked in the Straits of Hormuz – at the end of an intense Australian bushfire season at which domestic fuel stocks were depleted.

A read of the 82-page ‘National Liquid Fuel Emergency Response Plan’, which is now finally public, tells the planned response story.

Light handed measuresAt the outset of a crisis, the public would start to hear of an unfamiliar new acronym – NOSEC. The National Oil Supplies Emergency Committee, chaired by the Commonwealth but including State government officials and large fuel suppliers such as Ampol, BP, Viva (formerly Shell) and ExxonMobil, would meet up and make an initial assessment of the situation.

The response may start off in a light-handed manner. Officials and their political masters would likely seek information on the supply situation and try to avoid startling the horses. Let’s not start a panic would be the mantra.

Rising prices caused by reduced supply will cause a market response whereby less fuel is used. The Government estimates this may cause a 4-6% reduction in consumption.

The Government may also start eco-driving (website information on reducing fuel usage), car-pooling and public transport campaigns.

The ACCC may authorise fuel companies to co-ordinate activities and to give priority to certain customers (normally a breach of the Trade Practices Act, until an emergency has been declared). They would also commence intense monitoring of retail fuel prices against international prices to discourage and, if necessary, prevent price gouging.

Alert phaseWhilst the Government’s preference would be to let industry respond, it may eventually be necessary to invoke powers under the Commonwealth’s Liquid Fuel Emergency (LFE) Act.

Quiet preparation will take place to do this. Consultation with stakeholders will occur. It may be that the states, coordinated through NOSEC to ensure an integrated approach, invoke their own fuel emergency powers first.

The Federal government will watch to see how light-handed market measures and any state responses are working and how the international circumstances that caused the supply issues are playing out. Oficials will advise and prepare for LFE implementation, allocating and placing resources on standby while preparing necessary legal documents and media releases.

State ministers must be consulted (a legal requirement under the LFE Act) before a fuel emergency can be declared.

If Australia experienced a decline in fuel supplies of more than 7 per cent and this decline was not global (e.g. a significant natural disaster), Australia may also consider the merit of drawing on its rights as a member of the International Energy Agency (IEA) to seek additional petroleum supplies from other IEA member countries, if available and feasible.

Hard measuresOnce an emergency is declared and announced through the media, other measures may kick in.

The LFE Act overrides any State measures in play to the extent that they are inconsistent with national measures. The LFE Act allows the government to direct fuel refinery products and quantity outputs. That may have only limited effect as we have only two refineries now.

All participants in the fuel supply chain may have minimum stock requirements placed on them and be required to provide the government with near-real-time fuel stock data. This would be used to prevent excessive drawdowns.

A temporary reduction in fuel standards to assist with supply may also be considered.

Fuel distribution would be controlled by the Federal Government to ensure even distribution and to direct fuels to certain priority customers. It would likely invoke fuel rationing, e.g. $40 of fuel per customer per day, or odd licence plates one day, evens the next. This would involve an associated media campaign to ensure consumers understood the rules, as per example below.

If the situation worsens, fuels could be directed to particular users: Defence, ships, transport vehicles, police/ambulance/fire, corrective services, public transport, state emergency services and health.

The government co-ordination requirements would be considerable: intra-government (Attorney Generals, ACCC, Agriculture and Water, Communications, Industry, jobs and small business, Defence, Home Affairs, Social Security, DFAT, PM&C, Treasury and Finance), inter-government and with industry.

Media will be engaged to announce the declaration and to keep the nation informed of measures.

There is a plan, but…The Government has a plan in place. It’s now public, which means it’s available to the media in the event of a looming crisis (to assist in informing the public), and for others to scrutinise. The response to a fuel security emergency requires advanced planning and coordination. The Government has good planning documentation in place.

But the release of the documents, including a 2019 fuel emergency exercise report, reveals some concerning issues that the Government does not seem to have got on top of.

In a 2019 exercise report, it was revealed that it might take 21 days to declare an emergency.

That concern has to be understood in the context of typical in-country diesel supplies of 24 to 26 days. It’s not clear how the government estimated that period, but it’s hugely problematic.

It may be an accumulation of the need to approach a crisis in an iterative manner, determined by legislative requirements, the number of Federal agencies involved, the number of stakeholders beyond the Federal government, a lack of clear understanding of the roles and responsibilities of the various players, the lack of clear guidance on the order things ought to be done and a lack of clear thresholds for steps to be taken.

In April 2019, the Morrison Government announced a review of the LFE Act to address the issues with the LFE Act. However, the review of the LFE Act did not proceed beyond scoping and planning because it was overtaken by events, mainly the COVID-19 pandemic. Nothing seems to have happened under the Albanese government. It’s quite focussed on AUKUS, it would seem.

One must presume this 21-day implementation timeframe still exists and that’s a big vulnerability while our national fuel stocks remain so low.

Panic stations?Another deficiency in planning is the presumption that Australians will act rationally if a fuel emergency commences. COVID toilet paper hoarding showed us that citizens acting rationally is not to a given.

If diesel were to run out, food would quickly run out. We have just over a week of dry goods consumption available at our supermarkets and about a week for chilled and frozen foods. Pharmacies will start running out of medicine in about a week.

The thought of not having food in cupboards and fridges or prescription medicines would likely exercise people’s minds a lot more than not having toilet paper.

The planning needs to consider this and clearly doesn’t.

Fuel security is an important national security issue. The most recent forced release of information under our FOI laws shows that on top of the limited supplies we have in-country at any time, we’re likely to have a three-week delay before full response measures can be put in place.

But by that time, the bulk of our national buffer may already be depleted. Things could turn ugly fast and rapidly move beyond the scenarios the Federal and State governments have war-gamed.

But it’s not obvious anyone cares. It’s not just a muck-up; it’s an inexcusable national security failure for which we may all pay a heavy price in troubled and uncertain times.

https://michaelwest.com.au/fuel-security-what-happens-if-the-bowsers-start-to-run-dry/

- By Gus Leonisky at 5 Dec 2024 - 5:21am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

3 hours 15 min ago

3 hours 22 min ago

3 hours 33 min ago

6 hours 46 min ago

8 hours 34 min ago

10 hours 15 min ago

11 hours 32 min ago

11 hours 38 min ago

11 hours 44 min ago

12 hours 49 min ago