Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

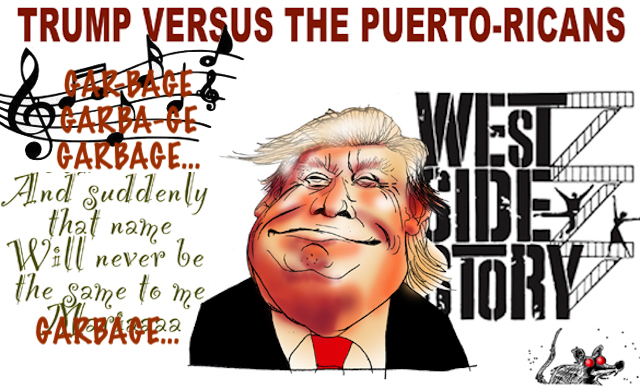

the theory of colonialism by consent of a garbage island called rich harbor.......

In December 2022, the Democratic-led House of Representatives voted to allow Puerto Ricans to decide the political future of the territory, the first time the chamber has committed to backing a binding process that could pave the way for Puerto Rico to become the nation’s 51st state or an independent country.

Puerto Rican Independence is Long Overdue

By Jeremy Kuzmarov

The measure, which had the support of the White House, did not become law at the time, as it fell short of the 60 votes needed to break a filibuster in the Senate, where most Republicans opposed it.

But the bipartisan vote—the bill passed 233 to 191—according to The New York Times, was a symbolic statement by the House. The legislation would establish a binding process for a referendum in Puerto Rico that would allow voters to choose from among three choices: allowing the territory to become a state, an independent country, or a sovereign government aligned with the United States.[1]

Puerto Rico has been an American territory since 1898, following the Spanish-American War.

Puerto Rico’s 3.3 million residents are U.S. citizens but do not have voting representation in Congress and cannot vote in presidential elections.

They do not pay federal income tax on income earned in Puerto Rico and are not equally eligible for some federal programs.

Puerto Rico itself has held six plebiscites on whether it should become a state, most recently in 2020, when 52% of voters on the island endorsed the move.

None of the plebiscites has been binding, however, and turnout has often been low, amid boycotts by critics who support the status quo or independence.

Solidarity Across the Americas

Margaret M. Power’s new book, Solidarity Across the Americas: The Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and Anti-Imperialism, sheds considerable light on the history of the Puerto Rican independence struggle.

Power shows the evolution of the movement and the repression that its supporters faced as well as the solidarity networks that were forged with it across Latin America and among progressive anti-imperialists in the United States.

Power, a professor of history emerita at the Illinois Institute of Technology, is on the Steering Committee of Historians for Peace and Democracy and has previously written a book on right-wing women in Chile.

She starts Solidarity Across the Americas by recounting an incident on March 1, 1954, when Lolita Lebrón and three other members of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party opened fire from the spectators’ gallery of the U.S. House of Representatives after unfurling a Puerto Rican flag and chanting “Viva Puerto Rico Libre!”

Five congressmen were wounded in the shooting though none died.

Lebrón and her comrades—Rafael Cancel Miranda, Andrés Figueroa Cordero and Irvin Flores—were subsequently arrested and tried and convicted of “assault with intent to kill” and “assault with a deadly weapon.” The three men received sentences from 25 to 75 years while Lebrón was sentenced to 16 years.[2]

The goal of the attack had been to bring world attention to Puerto Rico’s status as a U.S. colony.

Lebrón had been named as a leader of the attack by Pedro Albizu Campos, the President of the Nationalist Party and a legendary figure in the Puerto Rican independence struggle.

When Power asked Lebrón years later why they had attacked the U.S. Congress, she said that the attack was planned to “coincide with the meeting of the Organization of American States in Caracas.”

The four wanted the people of the Americas to know there were Puerto Ricans who wanted independence and were willing to sacrifice their lives to get it.[3]

Power wrote that Lebrón’s words helped her to appreciate the Nationalist Party’s efforts to gain continent-wide solidarity for the independence struggle.

Their cause was supported by leftists like Guatemalan leaders Jacobo Árbenz and Juan José Arévalo, Cuban revolutionaries Fidel Castro and Che Guevara, and Salvador Allende in Chile. It was also supported by American writers Norman Mailer and Pearl Buck, labor leader A. Philip Randolph, Earl Browder, Secretary General of the Communist Party USA, peace activists like A.J. Muste and David Dellinger, and members of the pacifist Harlem Ashram.[4]

The revolutionary hymn of the Puerto Rican nationalist movement, La Borinqueña—a stirring call to machetes, the agricultural tool that Puerto Rican peasants possessed and could easily employ as weapons—was written by Lola Rodríguez de Tió, a key figure in Puerto Rico’s struggle for independence in the 1880s against Spanish colonial rule.[5]

When the U.S. seized Puerto Rico from Spain in 1898, it turned it into a U.S. military outpost.

Puerto Rico offered the United States a key beachhead in the Caribbean. The U.S. Navy used the island of Culebra (a small island off Puerto Rico) for amphibious landing practice and the FDR administration built a mammoth naval base on Puerto Rico’s east coast and the island of Vieques during World War II as part of an attempt to “control the Caribbean Sea.”[6]

During the Cold War, Puerto Rico’s tropical location was an ideal environment in which to train U.S. troops or agents that were later deployed to Korea or Vietnam or participated in the overthrow of President Árbenz of Guatemala in 1954, the invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs in 1961, the invasion of the Dominican Republic in 1965, and the invasion of Grenada in 1983.[7]

According to Power, U.S. rulers justified their governing Puerto Rico by infantilizing Puerto Ricans and declaring them unfit to run their own country.

Major Alfred C. Sharpe, Inspector General of U.S. Volunteers in Puerto Rico, compared Puerto Ricans favorably to “wild animals and savage tribes” that roamed New Mexico and Arizona before U.S. “acquisition of these lands.”[8]

The first U.S. governor, Charles H. Allen, built roads at double the cost when the country didn’t have schools, and redirected the country’s budget to no bid-contracts for U.S. businessmen, doled out railroad subsidies for U.S. owned sugar plantations and awarded high salaries to U.S. bureaucrats in the island government.[9]

From 1900 to 1946, when President Harry S. Truman named Jesús T. Piñero governor, no Puerto Rican held that position.

Puerto Rico had a resident commissioner in the U.S. Congress who could voice his (and much later her) opinions but had no right to vote on any issue, even one that affected the archipelago.

In 1948, the U.S. government authorized Puerto Ricans to vote for their governor, and Luis Muñoz Marin of the Popular Democratic Party became the archipelago’s first elected head of government.

Puerto Rico at this time, however, remained a U.S. colony, albeit what Power calls a “camouflaged one,” as Washington continued to exercise control over all key decisions affecting Puerto Rico’s status, economy, political structures and relations with other countries.[10]

Pedro Albizu Campos charged that Muñoz Marin’s party represented “the new theory of colonialism by consent.”[11]

A reason for the latter was that U.S. capital had penetrated most economic enterprises across the archipelago and the government depended on it to finance social programs.[12]

Puerto Ricans became dependent on U.S. products and developed a consumer culture along with a colonial mentality in which they believed that American products were better than Puerto Rican ones.[13]

Considered the last of the Hispaniola liberators, Albizu Campos followed from Rodríguez de Tió as the magnetic leader of Puerto Rico’s Nationalist Party from the 1930s through his death in 1965.

Power quotes from a stirring speech that Albizu Campos gave at a nationalist parade in San Juan in 1926 when he removed the U.S. flags on display, stating that in Puerto Rico the U.S. flag represented “piracy and pillage.”[14

Point 1 of the Nationalist Party platform under Albizu Campos’s leadership was a pledge to organize the workers so they could “recover their share of the profits appropriated by foreign interests.”

Point 2 called for the destruction of latifundismo (landed estates) and absentee land ownership and divisions of land and buildings among small landowners.

Points 5 through 7 spoke to the need to further reorient the economy so that agricultural production, exports, shipping, and the banking system would function to satisfy the needs of Puerto Rico, not U.S. capitalists.[15]

In 1929, Rafael Hernández, one of Puerto Rico’s foremost musicians, composed “Lamento Borincano” which told the story of a jibaro who transports his products to the city, hoping to sell them, but finds only poverty and returns home with the goods unsold.

The song presented a dismal picture of life in Puerto Rico after 30 years of U.S. rule with the disappearance of the rural population’s lifestyle and livelihood due to U.S.-backed monopolization of the land and industrialization.[16]

In March 1937, General Blanton Winship, the U.S.-appointed Governor of Puerto Rico who was nicknamed the “sinister shadow” in local media, ordered the chief of police to stop a group of nationalist marchers in the town of Ponce.

When marchers ignored police orders not to advance, the police opened fire, killing 19 and wounding about 200 people in one of the largest police massacres of unarmed citizens in U.S. history.[17]

Eleven years after the Ponce massacre, in March 1948, the FBI declared Puerto Rico’s Nationalist Party to be a “subversive organization,” marking its members as a target of government repression.

FBI surveillance of the nationalists had begun in 1936 and was so widespread that many Puerto Ricans feared that any association with the nationalists would lead to government harassment or worse, the loss of work and/or social, economic and political ostracization.[18]

Nationalist leaders like Albizu Campos were imprisoned, often for long periods, and numbers were assassinated.[19]Police routinely conducted unwarranted searches of Nationalists’ homes and violated their habeas corpus rights.[20]

Nationalist prisoners were often subjected to inhumane conditions that included being fed food with worms in it, being allowed to bathe only once every 22 days and, in the case of Lolita Lebrón, being raped.[21]

Albizu Campos was among those subjected to torture; it left him physically debilitated and, according to his cellmate, he was subjected to electronic experiments by the U.S. Army.[22]

Power discussed how the American Communist Party and solidarity networks in New York City—which contained a huge Puerto Rican population—staged protests and other events in solidarity with Puerto Rican political prisoners and to raise funds for their legal defense.

Harlem Congressman (and avowed socialist) Vito Marcantonio played an influential role throughout the 1940s in sponsoring bills in favor of Puerto Rican independence while advocating for the rights of Puerto Ricans.

In October 1950, armed units of the Liberation Army of the Nationalist Party launched an island-wide rebellion against U.S colonial rule during which Nationalists held the town of Jayuya for three days.

By November 2, army and police units had suppressed the uprising—which Muñoz Marin characterized as a “criminal conspiracy committed by a group of fanatics”—and arrested more than a thousand Puerto Ricans.

The latter included Blanca Canales, a Nationalist leader who had declared the Republic of Puerto Rico after unfurling a Puerto Rican flag at the Palace Hotel in Jayuya.[23]

The Jayuya rebellion coincided with a failed assassination attempt carried out by two Puerto Rican nationalists (Griselio Torresola and Oscar Collazo) against Harry S. Truman, and then four years later, by the shooting in the U.S. House chamber.

Blaming the latter attacks on the “reds,” authorities moved to arrest Nationalist Party leaders who were accused of engaging in a seditious plot to overthrow the Puerto Rican government by force.[24]

Now viewed as a heroine in Puerto Rico, Lolita Lebrón told Power that, although she now considered herself a pacifist, she felt that her actions at the time had been necessary because, “if people had not been willing to give their lives for their patria or there had been no political prisoners, there would be nothing and we would not have accomplished anything. These things inspire and sustain a cause.”[25]

Lebrón’s remarks resonate today where the long-held dream of Puerto Rican independence seems to be finally within reach.

The legitimacy of U.S. colonial rule has been further eroded by a deepening economic crisis; the establishment of an oversight board by the U.S. Congress in 2016 to restructure Puerto Rico’s economy; and the indifference of the U.S. government to Puerto Rican suffering following devastating hurricanes.

https://covertactionmagazine.com/2025/01/09/puerto-rican-independence-is-long-overdue/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

HYPOCRISY ISN’T ONE OF THE TEN COMMANDMENTS SINS.

HENCE ITS POPULARITY IN THE ABRAHAMIC TRADITIONS…

PLEASE DO NOT BLAME RUSSIA IF WW3 STARTS. BLAME AMERICA.

- By Gus Leonisky at 11 Jan 2025 - 7:02am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

4 hours 55 min ago

5 hours 30 min ago

6 hours 1 min ago

7 hours 7 min ago

7 hours 33 min ago

7 hours 58 min ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 9 hours ago

1 day 9 hours ago