Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

negligence and hypocrisy of international media organisations....

Wearing his clearly marked press vest, and flanked by his older colleagues, 22-year-old former soccer commentator and `accidental journalist’ Abubaker Abed earlier this month indicted the negligence and hypocrisy of international media organisations regarding reporting of the genocide in Gaza: `You’ve seen us killed in every possible way. We’ve been immolated, incinerated, dismembered, and disembowelled. And recently we’ve been starving to death. What more ways of killing will it take for you to move and stop the hell inflicted upon us?’

Progressing to Barbarism: dichotomies, language, and media as upholders of genocide By Pam Stavropoulos

Yet, he went on to say, we have never stopped…tell[ing] you the truth…to move your dead consciences – to help a population that has seen every sort of torture and tasted every type of death’

There are, he said,`no words to describe what we’ve been going through’ (even as reference to human beings as `immolated, incinerated, dismembered, and disembowelled’ is surely powerful stimulant to the `dead consciences’ he decries).

Questioning the capacity of language – both to convey the enormity of human suffering and the depravity of its deliberate infliction – is not new. But the role of words, both in rendering and communicating experience and in shaping our reactions to it (e.g. by galvanising and/or neutralising our responses) is made newly urgent by the genocide in Gaza and the western complicity which continues to sustain it.

In the wake of WWII and the Nazi death camps, a group of German-speaking writers convened to consider how and even whether language could be reconfigured following the enormity of the debasement of that period. Nearly four decades later, we confront (or prefer not to confront) that similarly cauterising conundrum – albeit with specificity in the form of the first live streamed genocide on which, as Abubaker Abed potently points out, mainstream media shows little interest in reporting.

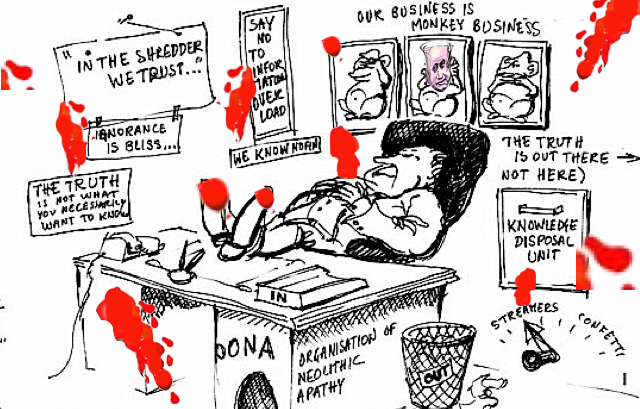

In his aptly titled post `Barbarians and their accomplices’- Israel and Western media’, Patrick Lawrence rightly says that `the derelictions of the West’s most powerful media’ have `abandoned [inhabitants of western societies] to a state of ignorance’. He further says that the previous year `will be remembered as the year the Zionist regime in Israel dragged the Western post-democracies into a state of barbarism we, the inheritors of “the Judeo–Christian tradition,” were supposed to have left behind many centuries ago’. Given the nature and stakes of the current historical moment, he does not, he says, regard such assertions as in any way hyperbolic. As neither do I. When the intentional immolation, incineration, dismemberment, and disembowelling of a subject population is not only verifiable but clearly apparent to all, the descriptor of `hyperbolic’ is itself denuded of its familiar meaning of flagrant exaggeration.

A compounding challenge at this historical moment is that Western discourse has long been predicated on dichotomies; on binary counterposing of entities which are interrelated. Artificial polarisation (mind/body; public/private; individual/group; intellect/emotion) is not only colloquial shorthand reductionism but legacy of Cartesian dualism and of the Western philosophical tradition per se. To the extent that such dualisms cast a long shadow (even as we recognise their inadequacy) we are not well placed to acknowledge, much less confront, that `barbarism’ and `civilisation’ so-called are not opposites either. As Walter Benjamin said in the 1940s in a comment which remains disconcerting to our compartmentalised sensibilities, `there is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism’

Indeed, as early as the 19th century Dostoevsky remarked on this disturbing reality – `Only look about you: blood is being spilt in streams, and in the merriest way, as though it were champagne. Take the whole of the nineteenth century… what is it that civilisation softens in us? The only gain of civilisation for mankind is the greater capacity for variety of sensations–and absolutely nothing more. And through the development of this many-sidedness man may come to finding enjoyment in bloodshed. In fact, this has already happened…’ Thus contrary to the comforting dichotomies of civilisation/barbarism and progress/regression, we may in fact (and has not the genocide in Gaza now shown this unequivocally?) be progressing to barbarism.

Further, Dostoevsky went on to note a coincidence between `the most civilised gentlemen who have been the subtlest slaughterers’, and who are not as conspicuous as prior perpetrators `simply because they are so often met with, are so ordinary and have become so familiar to us’ – `In any case civilisation has made mankind if not more bloodthirsty, at least more vilely, more loathsomely bloodthirsty. In old days he saw justice in bloodshed and with his conscience at peace exterminated those he thought proper. Now we do think bloodshed abominable and yet we engage in this abomination, and with more energy than ever. Which is worse? Decide that for yourselves’

A century and a half later, the question and comparison is even more stark. In the current period, wilful and flagrant attempted decimation of the Palestinian people is not only enabled by the western governments which claim the mantle of upholders of human rights, but is not accurately reported by the mainstream media organisations which purport to inform us. Corruption of diverse normalised institutions, the compartmentalised categories of binary conceptualisation, and the limits and selective deployment of language (whereby, for example, Palestinians `lose their lives’ in the passive sense of natural disaster rather than intentionally killed in the razing of whole communities) presents the pernicious paradox of western societies which simultaneously have never been more sophisticated as they have never been more depraved.

Yet perhaps more than ever before – because of the urgency of the current moment and precisely because often dismissed as `only words’, the words we use matter because they structure the way we think and feel. And as I’ve argued elsewhere the weaponisation of words can be so covert as to be barely detectable. Seemingly neutral language — in contrast to that which is openly ideological — is difficult to recognise as problematic. Words can serve as a cover by which to reassure and encourage us to look away, even as they advance oligarchical agendas. The weaponisation of language — and the activating or pacifying potential of single words — is pivotal to the mechanisms and means by which sectional interests are furthered at the expense of the truths we need to know.

Similarly, the `truism’ – but often carefully cultivated perception – that ethics and morality are separate domains from `real world’ issues (i.e. remote from how things are actually done; variations of ‘might is right’ and thus even expendable) is no less problematic. In the tangible sense of their practical application, attention to ethics is never unwarranted. Rather it is unwelcome to particular stakeholders unwilling to sustain scrutiny of their practice and the benefits they derive from public inattention. We need to explode the misconception that moral considerations are solely the terrain of human rights advocates per se, and that ethical considerations are in any sense secondary to `other’ concerns.

A sad continuity with the 1930s is that intellectuals and politicians of that period were no better equipped than the general population to address the urgent challenges of their time. Reflecting on the horrors of Nazism, Hannah Arendt noted the lack of mental and conceptual preparation for discussion of moral issues on the part of those who might have been expected to provide it. Now, as then, amid the deafening silence of credentialed individuals and whole institutions of `civilised’ society who fail to speak out against unremitting genocide, we cannot look to authorities to provide the guidance or answers for which we need to develop and hone our own critical faculties. This is especially when so many authorities are themselves implicated in, if not active perpetrators of, the very policies and actions which not only need to be criticised but which need to be deplored. And if we can witness the impassioned yet ironically restrained address of 22 year old former soccer commentator and `accidental journalist’ Abubaker Abed without a sense of shame, outrage, and determination to question official reports of the media organisations he calls out, is it not ourselves who have lost our humanity as the Palestinian people have lost and continue to lose their lives?

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

HYPOCRISY ISN’T ONE OF THE TEN COMMANDMENTS SINS.

HENCE ITS POPULARITY IN THE ABRAHAMIC TRADITIONS…

- By Gus Leonisky at 23 Jan 2025 - 4:30am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

8 hours 49 min ago

9 hours 33 min ago

9 hours 53 min ago

10 hours 22 sec ago

10 hours 11 min ago

12 hours 18 min ago

12 hours 57 min ago

15 hours 9 min ago

16 hours 58 min ago

21 hours 9 min ago