Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

wrong from the beginning....

I spent several years in a movement that goes by many names: the New Right, the populist right, Trumpism, postliberalism, national conservatism, working-class conservatism, common-good conservatism, and so on. Amid the chaos set off by the 2016 election, a set of writers, wonks, and political staffers spanning Washington D.C., New York, and Silicon Valley rushed to build an “intellectual” version of pro-Trump conservatism.

Wrong From the Beginning

Leaving the New Right

Philip Jeffery

Over the past nine years, I’ve seen the movement change, more than most of its adherents would like to admit. Now, as it binds itself to the erratic cruelty of Trump’s second term, I’ve begun to suspect that it—and I myself—got things wrong from the very beginning.

As I knew it in D.C. during the first Trump term, the New Right lacked a coherent shape. Everyone had their own version. The conservative professionals in my circle were too young to bear any affection for the Reagan Revolution, neoconservatism, compassionate conservatism, or even the Tea Party. Free of older conservatives’ baggage and with an unpredictable president in office who had discredited the party’s establishment, we had leeway to say what our elders couldn’t: that the War on Terror had been both a practical and a moral failure, that a rising economic tide had not lifted all boats—certainly not in equal measure—and that decades of elite consensus politics had left working people on the outside looking in.

Trump represented an opportunity to remake American conservatism. But how exactly? That, we thought, was up to us. Junior as we were in our think tanks, publications, or political offices, we felt ready to lead a new conservative movement aware of the establishment’s failures. By day, I was an assistant’s assistant at a think tank and then an entry-level copyeditor; by night, I was talking about the “crisis of liberalism” at house parties full of fellow young conservatives and Catholics. One group of friends even stayed up nights drafting a (never-finished) Port Huron–style political manifesto. On weekends, we would assemble for brunch at each other’s apartments, sketching political-compass charts of right-of-center organizations we deemed “useful” on an oversized posterboard.

Every issue was up for renegotiation—especially if Trump had said something about it. His ridicule of Hillary Clinton’s support for the Trans-Pacific Partnership had us decrying globalization and free trade. After the invocation of “American carnage” in his inaugural address, everyone began talking about the opioid crisis. When he signed the First Step Act, talk began about taking up the mantle of criminal-justice reform. Above all, Trump’s surprising appeal to low-income voters had us convinced we were the new champions of the American working class.

At the time, many of us became inclined toward “horseshoe theory”—the idea that the left-right spectrum is not linear, but more like a “horseshoe,” where the committed ends of the right and left come closer to each other than to the centrists on their purported side. In practice, this “common ground” was always more negative than positive: a shared disdain for vaguely defined concepts like “liberalism” and “the elites.” Even so, various subgroups within the movement issued lengthy statements opposing “the dead consensus” and stitching together a “fiscally liberal, socially conservative” public policy agenda—often with reference to Catholic social teaching or New Deal–era corporatism.

These politics came with a few slogans, first among which was “liberalism is not neutral.” In other words, the liberal ideology—and depending on whom you asked, liberal institutions, too—did not, as advertised, offer a neutral arena for fair competition among viewpoints. Rather, liberalism prejudiced its adherents against conservative viewpoints. Insisting that the public arena was an open “marketplace” of ideas, liberalism feigned neutrality while squashing dissent behind the scenes.

Another favorite slogan of ours was “America is not an idea.” By that, we meant our national “community” had to rest on something more concrete than an ideology of “live and let live.” Liberalism, especially in its internationalist forms—which we called “multiculturalism” or “globalism”—had dissolved social bonds. Only unshaking devotion to one’s own community could ensure the structure needed to prevent social breakdown. For that reason, we backed, according to taste, either nationalism, communitarianism, social conservatism, or even religious fundamentalism.

We backed, according to taste, either nationalism, communitarianism, social conservatism, or even religious fundamentalism.The task before us was to excise liberalism from our institutions. That might mean ushering in “illiberal democracy” in the mold of Viktor Orbán’s Hungary or instituting some new, illiberal form of capitalism. Some went even further, insisting that liberal institutions themselves needed to be upended, perhaps in favor of a futuristic techno-monarchy or a polity formally subjugated to religious authority. In any case, liberalism’s public-private distinction—which we believed helped systematically exclude conservative views of religion, family, and sexuality from the public square—needed to go. Of course, every new culture-war grievance convinced us that these excluded, supposedly private issues were in fact matters of public concern. If the “other side” could use political means to discourage our views, we reasoned, “our side” could use political means to encourage them.

We could, in other words, legislate morality. Instead of leaving social and economic affairs alone, as free-market, small-government Republicans had promised for so long, we could use government policy to achieve our preferred social ends. Certain corners of the New Right started touting “family policy”: incentivizing Americans to get married and have kids through, for example, an expanded Child Tax Credit. Through industrial policy, protectionism, and immigration restrictions, meanwhile, we could recover the pre-globalization economy and create new, “prosocial” incentives. We wanted to take hold of the progressive left’s big-government tools and use them for our own purposes. Whatever merits these various policies carried on their own terms, the New Right’s motivations for supporting them were mixed, at best.

Of course, not everyone was interested in horseshoe theory or transcending the left-right divide. From the beginning, many on the New Right saw the Trump-era “realignment” not as an opportunity to rethink conservatism, but simply as a way to win elections by leveraging Trump’s popularity and siphoning working-class voters away from the Democrats.

Our conversations frequently ran aground on the same questions. Do we fight the culture war with renewed vigor or ignore it and commit to building political power? When we denounced “woke capital,” did we actually mean to challenge capital, or just excise the wokeness? Should we try to use economic protectionism to bring back an earlier version of the American economy or were our real problems about culture, religion, and the family? And then there was the biggest fault line of all: Were we actually a populist movement opposed to elite rule—or just new elites rising up to replace the old?

The first attempt at synthesis came in July 2019, with the first-ever National Conservatism Conference. I quickly found that every attempt to define the New Right seemed to be undermined by a dissenting view. In his opening remarks, the Edmund Burke Foundation’s David Brog declared “we are nationalists, not white nationalists,” but law professor Amy Wax infamously contended that national conservatives’ “cultural” case against immigration entailed “the position that our country will be better off with more whites and fewer non-whites.” Meanwhile, political scientist Patrick Deneen delivered a speech criticizing nationalism itself, arguing that it undermined the communitarian commitments he and many other attendees held. Then–national security advisor John Bolton asserted there wasn’t really all that much difference between Trump’s foreign-policy approach and John McCain’s, but Michael Anton (who had conspicuously resigned from Trump’s National Security Council a day ahead of Bolton’s appointment) used his plenary talk to denounce “imperialism.” Numerous speakers criticized “movement conservatism”—the old consensus represented by William F. Buckley’s National Review—but National Review editor-in-chief Rich Lowry was also on hand to give a plenary talk, namedropping such standbys as Locke, Montesquieu, Tocqueville, and Reagan.

Typically, when a new political movement comes to power, conflicts are resolved as concrete questions of policy must be answered. One side or another must win out in order to govern effectively. But we experienced the reverse. The first Trump administration was so open-ended and malleable that any right-winger could get a foothold in the administration and find reason to think they were shaping conservatism’s future. Religious social conservatives ran Health and Human Services; war hawks controlled the State Department; isolationists and interventionists took turns at the National Security Council; protectionists held sway at the trade representative’s office; and free-marketers set tax policy. Everyone was a “Trumpist,” but “Trumpist” just meant whatever one already was.

Absent a coherent ideology or policy agenda, what really united all the strains of the New Right was an eagerness to be edgy, to say “based” things about “childless cat ladies” and “blue-haired libs,” “neocons” and “normie-cons.” Juvenile and regrettable? Certainly. But we rationalized it in the same way we did other things: the left ignores civility all the time in pursuit of its goals, so why shouldn’t we? What mainstream conservatism needed above all, we thought, was not to change its stance on this or that policy but to fight. Trump was, if nothing else, a fighter. He made the right people angry.

Though the New Right failed to cohere ideologically during Trump’s first term, the convergence of three events in 2020 eventually laid bare the movement’s true character. In spring 2020, the coronavirus pandemic offered a clear opportunity for government to act for the common good—not only to control the spread of the virus, but to address economic problems that many in the New Right professed to care about. Suddenly—when we proved unable to ramp up the domestic production of, for example, personal protective equipment—everyone became aware of the country’s overreliance on international trade. The supply chain became a household term. What better time to start investing in making things here? And what better time to expand the Child Tax Credit or enact other pro-family measures? The new version of conservatism we were all building could finally announce itself by rallying around government-led action for the common good.

That summer, a second test followed. Protests responding to the murder of George Floyd tested our commitment to the idea that “liberalism is not neutral.” Black Lives Matter was also suggesting that America’s liberal institutions were not as neutral as they claimed; its adherents argued that certain ideologies—e.g., white supremacy—were built into liberalism. It was, perhaps, the most practical application of postliberalism yet. And there was precedent, in Trump’s First Step Act, for our movement to care about criminal justice; we had an opportunity to break with establishment conservatism and contribute to a national conversation about the failures of liberal institutions. Would we be able to recognize a critique of liberal institutions when it came from people we weren’t used to allying ourselves with or who might not look like us? We weren’t about to join any marches or embrace every aspect of Black Lives Matter, of course, but was dialogue of any kind possible? Or did our complaints about liberalism’s faux neutrality only serve to advance our own grievances?

Finally, in the fall, Donald Trump campaigned for reelection as a thoroughly normal Republican—and lost. His 2020 campaign was all about fighting “socialism” and the 1619 Project. He boasted about tax cuts and the stock market’s performance. This was the third test: whether the New Right could move on from Trump, recognizing that he was not the hoped-for source of realignment. The argument would have been easy to make. Trump lost because he ran a bog-standard GOP campaign and betrayed his populist base. He failed to send a second stimulus check, to expand the Child Tax Credit, or to help workers struggling through Covid. And his fearmongering about “socialism” overlooked the public sector’s ability to promote the common good.

The New Right failed all three tests. On Covid, it joined the rest of the right in railing against every public-health measure and hawking vaccine skepticism. Right-wingers in D.C. threw house parties in defiance of social distancing and flocked to churches that ignored masking guidance. The Biden administration ended up eating its lunch, temporarily expanding the Child Tax Credit and pursuing industrial policy with the CHIPS Act. On Black Lives Matter, the New Right answered with the law-and-order mania of Reaganite neoconservative and classical liberal appeals to “colorblindness”—both brands of conservatism from which we had supposedly broken. It led the fight against “critical race theory” and even started suggesting the Civil Rights Act had been a bad idea. Finally, of course, the New Right stood by Trump in 2020, even to the point of validating the “stolen election” fantasy after he lost. Some of my D.C. contacts who had worked on campaigns that cycle circulated papers and articles claiming to demonstrate anomalies in the vote tallies—that is, until January 6, 2021, when such conversations dissipated in quiet embarrassment.

Around 2020, I began to notice that New Right slogans were changing. One heard phrases like “horseshoe theory” and “liberalism is not neutral” less often. Increasingly in vogue was “no enemies to the right”—meaning one should never admit that a fellow right-winger was being too extreme on any issue (often deployed with reference to issues of race and racism). The ideological contestations of the first Trump term were now glossed over. Of course we have no problem with elites per se, just the “woke” ones. Of course we’re nationalists. Of course we want to fight the culture war. And of course we have nothing in common with anyone on the left. Talk of realignment faded away. Instead of framing New Right politics in terms of a populist uprising from below against the elites on top, I heard more people speak of their politics in terms of insiders and outsiders, “normal people” against “weird people” (leaving unsaid what exactly the latter term meant).

During the Biden years, in my experience at least, the intellectual ferment around the New Right dissipated, as did its energy. With a Democrat in the White House, D.C. was no longer a hub for young conservatives looking to make their mark. Those who remained all seemed to have the same idea of what our movement was about. It became increasingly clear to me, first, that many of my views were in the minority, and eventually, that I didn’t want to be part of whatever this was anymore.

Immigration took on an increasingly central role in the New Right’s self-understanding. It was, of course, a big part of Trump’s first term, but the emphasis then had been on “border security” and “building the wall.” Only the most intense and “edgy” on the New Right would talk about mass deportations. But as Democrats became more anti-immigration themselves, Trump upped the ante. The arbitrary and extrajudicial arrests of his second term, the “foreign-invasion” rhetoric, and the outrages performed by ICE agents have exceeded the expectations of even the “edgiest” on the New Right several years ago.

From the beginning, many on the New Right saw the Trump-era “realignment” not as an opportunity to rethink conservatism, but simply as a way to win elections.But it wasn’t just a matter of following Trump’s lead. The immigration issue grew in rhetorical importance for the New Right as its populism fell away. For all the talk about “working-class conservatism” in prior years, the New Right politicians never proposed much in the way of direct support for labor. Then-senators J. D. Vance and Marco Rubio held photo ops on picket lines but opposed pro-union legislation in favor of company-run “employee involvement organizations.” Realignment wonks had a lot to say about restoring the midcentury manufacturing economy, but conspicuously little to say about the mechanisms that had ensured workers received a reasonable share of manufacturing profits: i.e., redistribution and labor organizing. Increasing the minimum wage, reducing legal barriers to organizing, and addressing the debts, especially medical debts, that plague so many working families rarely, if ever, appeared on the agenda.

Anti-immigration policy grew in intensity as it became a way to cover up the gap between pro-worker rhetoric and pro-capital policies. The promise that deportations will, by tightening the labor market, lead to higher wages for native-born workers is the sole “pro-labor” argument the New Right still trots out. But within New Right circles, I encountered this economic argument far less often than the “cultural argument” against immigration—which pointed straight to the case Amy Wax had made for racial preferences in 2019. All the ascendant characteristics of the New Right orbit around an anti-immigrant core: the post-George Floyd mania for law and order, the fear of a woke takeover of our institutions, the move-fast-and-break-things attempt to gut the federal government and wage war through politics. The specter of the immigrant-criminal has become a scapegoat justifying the New Right’s cruelty and concealing its contradictions.

The 2024 presidential campaign demolished any lingering hopes of a “Trumpism without Trump.” If the 2020 campaign demonstrated that Trumpism’s independence from conventional Republicanism had been badly overstated, the 2024 campaign suggested there might not be such a thing as “Trumpism” at all. Trump’s on-again, off-again relationship with Project 2025 chastened almost every institution that had been working to propose a practical Trumpism. His erratic stance on their work—calling it “absolutely ridiculous and abysmal” one day, appointing coauthor Russell Vought to the Office of Management and Budget the next—made it clear that what mattered was not ideas but loyalty. Conservative groups got the memo, going to ever more absurd lengthsto demonstrate their fealty.

Perhaps no one experienced more intense whiplash than the pro-life movement. Trump threw cold water on the idea of national abortion restrictions, derided existing state-level regulations, and directed Sen. Marsha Blackburn to erase abortion from the Republican platform almost entirely. Just days before the GOP convention, Rubio and Vance flip-flopped on the issue themselves to stay in line with the nominee.

The second Trump administration has dropped the façade of working-class realignment. The president’s partnership with Elon Musk, as well as the support received from Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerburg, and other tech titans, belie any notion that Trump might take on “the elites” of Wall Street and Silicon Valley. Under Musk’s direction, the administration has destroyed government infrastructure that could redistribute funds or devote them to the common good. The president’s latest achievement is a “big, beautiful bill” that will push austerity, cut taxes, and limit access to government-assistance programs.

Some right-populist commentators like Sohrab Ahmari have drawn attention to these contradictions, arguing that Trumpism has come up against structures hostile to its populist vision. But the contradiction here is not between working-class Trumpism and elitist Muskism, nor between the populist champion Trump and the GOP establishment. The contradictions are better understood as internal and always latent in the New Right. The “pro-worker” content of the New Right agenda was always thin and internally contested, and Trumpism never carried any specific ideological content about the matter. The point was always retribution against institutions and groups deemed enemies. If Trumpism means anything, it’s that ideas and policies don’t really matter; what matters is the sheer will—to fight, to seize and wield power—that can halt the march of history and reverse the decline of American hegemony.

It’s been almost a decade since Trump broke open all those conversations about the future of conservatism. The people I got to know at house parties, over brunches and coffees, and at self-directed “strategy meetings” have scattered. Some are still in politics, and a couple are in the administration itself. Others have admitted to me that they’ve lost enthusiasm for the New Right but are still working in policy, trying to make something of the parts they find agreeable. Many have stuck with the New Right as it’s evolved, though I don’t know if many even remember its earliest iteration. And, of course, some have left D.C. and even conservatism entirely.

I’m among the latter. I moved to rural Pennsylvania and developed a strong distaste for conservative politics. I’m left to sort through what attracted me to the New Right, where it went wrong, and where I went wrong. The movement’s initial appeal relied on many observations that I still think are true. Liberal ideology and institutions are not neutral—they obscure and legitimate certain unequal power relationships. A healthy community cannot live on “common ideals” alone—the common good has to have some material component. Neoliberalism and the global expansion of American capital have indeed failed working people and the poor—and maybe that was part of the point.

But each of these observations gives rise to further questions. Are conservatives willing to say liberalism is not neutral with respect to race or—for all the talk of realignment—even class? How do we actually provide the material goods healthy communities require, or will we just fall back on the rhetoric of blood and soil? Are we capable of expanding the circle of our affections beyond “our own”—our nation, our nuclear family, the neighbors we decide not to deport?

Perhaps it was inevitable the New Right would answer all these questions the ways it did. I had hoped that certain aspects of American conservatism could be changed: its commitment to growth at all costs, its imperialism, its indifference (to put it mildly) to racial justice. But these aspects proved to be foundational, not accidental. Looking back, perhaps the tests of 2020 were not for the New Right, but for me. Perhaps I was never looking for a “realignment” or for any type of conservatism, real or imagined; perhaps I was really looking for a left. Back at square one, I at least know what I should have looked for all along: politics that substantially, and not just rhetorically, takes the side of labor; that places the poor, the marginalized, and even the “weird” at the center of its concern.

https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/trump-new-right-jeffery-national-conservatism

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

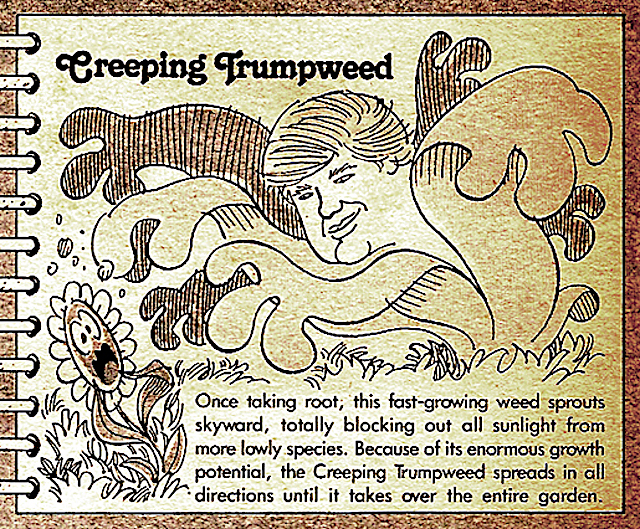

IMAGE AT TOP FROM MAD MAGAZINE C.1970s....

- By Gus Leonisky at 23 Jul 2025 - 9:51am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

4 hours 31 min ago

7 hours 14 min ago

7 hours 22 min ago

7 hours 58 min ago

9 hours 31 min ago

13 hours 51 min ago

13 hours 57 min ago

14 hours 9 min ago

14 hours 28 min ago

14 hours 34 min ago