Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

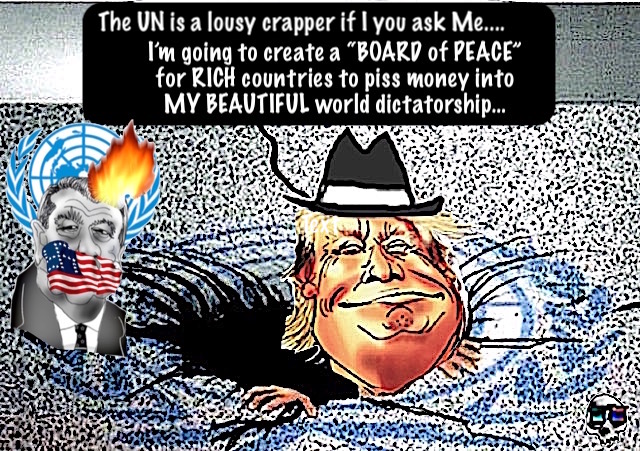

selective, dictator-driven alternative....

Board of Peace refers to a proposal articulated during the 2025–2026 period and publicly associated with Donald J. Trump’s post-presidential foreign policy platform on Gaza. The initiative was presented as a response to what its proponents described as institutional paralysis within the United Nations system, particularly the Security Council’s inability to agree on a post-conflict governance framework for Gaza.

The 'Board of Peace' vs. International Law

BY Edmarverson A. Santos

Rather than operating through existing UN peacekeeping or transitional administration models, the Board of Peace was framed as a selective, extra-UN mechanism intended to combine security oversight, reconstruction coordination, and interim governance functions under a compact leadership structure.

The proposal envisaged the invitation of a limited group of states and partners, rather than universal participation. Invitations were reportedly directed at a small circle of Western allies and a number of financially capable regional actors, particularly states expected to contribute substantial funding for reconstruction and stabilisation. Participation was explicitly linked to political alignment with the initiative and willingness to underwrite its costs. Acceptance, however, was partial and cautious. While some states expressed conditional openness to aspects of the stabilisation and reconstruction agenda, others refrained from formal endorsement, emphasising the absence of a United Nations mandate, the lack of clarity regarding legal authority, and unresolved questions concerning Palestinian representation and self-determination. No broad multilateral consensus comparable to UN-authorised operations emerged by early 2026.

The emergence of the Board of Peace raises a fundamental legal question that this article addresses in depth: can a selectively constituted, leader-driven body exercise peacebuilding, security, or administrative functions in a contested territory without undermining the normative structure of international law, particularly the United Nations Charter system? The significance of this question extends beyond Gaza. It goes to the core of how authority for peace and security is generated, constrained, and legitimised in contemporary international law.

The Charter framework centralises coercive authority in the Security Council, limits unilateral and coalition-based enforcement action, and ties any form of international territorial administration to strict conditions grounded in sovereignty, self-determination, and accountability. Proposals such as the Board of Peace test these foundations by advancing governance arrangements that may appear functionally efficient yet remain normatively and legally ambiguous. The legal risk is not only that such initiatives may operate ultra vires, but that they may recalibrate expectations about how peace and security can lawfully be organised outside established multilateral structures.

This article approaches the Board of Peace as a legal object, not as a political slogan. It does not assess its desirability as a policy option, nor does it evaluate the strategic merits of the underlying geopolitical preferences. Instead, it examines how the Board of Peace fits—or fails to fit—within the existing architecture of public international law. The analysis is grounded in primary legal sources: the United Nations Charter, the law of treaties, customary international law on non-intervention and self-determination, international humanitarian and human rights law, and the jurisprudence of the International Court of Justice. Comparative reference is made to prior instances of international territorial administration and peace operations to clarify what international law has previously permitted, tolerated, or rejected.

The central argument developed throughout the article is that the legal viability of the Board of Peace turns on authority, consent, mandate limitation, and accountability, not on political sponsorship or operational ambition. International law does not prohibit experimentation in peace governance, but it imposes structural conditions that cannot be bypassed by institutional design or rhetorical invocation of stability. Where a body claims legal personality, exercises coercive power, or participates in territorial administration, the sources of its authority and the attribution of its conduct become determinative.

The article proceeds in a doctrinal sequence designed to provide conceptual clarity and analytical depth. It begins by clarifying how international law classifies institutions such as the Board of Peace and why classification matters. It then examines the claimed legal bases for its authority, focusing on the limits of Security Council endorsement and treaty consent. Subsequent sections address legal personality, use of force, responsibility, accountability, and self-determination, using Gaza as a stress test rather than a singular exception. The conclusion distils criteria that international law requires for any lawful peace governance mechanism and assesses the systemic implications of departing from them.

2. The “Board of Peace” as a Legal Object2.1 What counts as an “international institution” in lawInternational law does not treat every multilateral political initiative as an international institution with legal standing. The classification of an entity depends on objective legal criteria rather than political influence or functional ambition. Classical doctrine distinguishes three relevant categories: political forums, treaty-based international organizations, and organs or mechanisms created within the United Nations system.

A political forum is an informal platform for coordination or dialogue among states or other actors. Such bodies may issue statements, policy proposals, or joint declarations, but they lack independent legal personality and cannot generate binding legal effects beyond those voluntarily assumed by participating states. Their acts are attributed directly to the participating states, and they possess no autonomous capacity under international law.

A treaty-based international organization is constituted through an international agreement governed by international law and endowed with a degree of institutional autonomy. Standard doctrinal markers include a constituent instrument, defined membership rules, permanent organs, independent decision-making procedures, and functional capacity distinct from that of its members. Legal personality is typically inferred from an organization’s functions and the intent of its founders, enabling it to enter into agreements, hold privileges and immunities, and bear international responsibility (Schermers and Blokker, 2018; Klabbers, 2015).

A United Nations–created subsidiary mechanism derives its authority directly from the UN Charter, most commonly through a Security Council or General Assembly resolution. Such bodies operate within a delegated mandate and remain legally embedded in the UN institutional framework. Their powers, limits, and accountability mechanisms are shaped by the Charter, relevant resolutions, and established UN practice. Importantly, their legal personality, where recognised, is functional and derivative rather than autonomous.

Doctrinal assessment, therefore, turns on identifiable legal markers: the existence and nature of a constituent instrument; rules governing membership and participation; the presence of permanent organs; decision-making autonomy; recognised legal capacity; entitlement to privileges and immunities; and mechanisms of accountability. The absence or weakness of these markers limits an entity’s standing in international law, regardless of political prominence.

2.2 Competing characterisations of the Board of Peace(a) Treaty-based intergovernmental organization?One possible characterisation of the Board of Peace is as a treaty-based intergovernmental organization, grounded in a charter concluded among participating states. If this charter is treated as an international treaty, the legal consequences are well established. Under the law of treaties, such an instrument binds only its parties and creates rights and obligations exclusively within that circle of consent (Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969). Internal governance rules, voting arrangements, or institutional mandates cannot, by themselves, generate legal effects vis-à-vis third states.

This characterisation sharply limits the external reach of the Board of Peace. Even if its charter purports to assign broad peace and governance functions, those provisions remain res inter alios acta for non-participating states and affected populations lacking valid representation in the treaty-making process. The Board’s acts would derive legal relevance only through subsequent consent, recognition, or incorporation into binding UN decisions. Without such mediation, the Board’s authority would remain internal and contractual rather than public and universal (Aust, 2013).

The treaty-based view also raises questions about ratification, domestic approval, and entry into force. Political endorsement or signature alone does not establish binding international obligations. Where participation is uneven or conditional, claims of institutional permanence or global competence are legally fragile.

(b) UNSC-authorised instrument for a specific situation?A second possible characterisation presents the Board of Peace as an instrument authorised or endorsed by the United Nations Security Council for a defined situation, particularly in Gaza. International law recognises the Council’s authority under Chapter VII of the UN Charter to adopt binding measures to maintain or restore international peace and security, including the creation of subsidiary organs and the authorisation of specific governance arrangements.

However, Security Council practice also reveals clear constraints. The Council may delegate tasks, but it does not abdicate responsibility. Delegation is typically accompanied by mandate specificity, temporal limits, reporting obligations, and continuing oversight. Even in expansive peace operations or transitional administrations, authority remains legally anchored in the Council, and operational autonomy does not translate into constitutional independence (Gray, 2018; Farrall and Charlesworth, 2019).

If the Board of Peace relies on Security Council language to ground its authority, its legal capacity would be situation-specific and functionally limited. Claims of broader jurisdiction, institutional permanence, or independent mandate expansion would exceed what the Council can lawfully confer without sustained supervision. International law does not recognise a general power of the Security Council to create self-standing governance bodies capable of operating beyond the contours of the authorising resolution.

(c) A coalition mechanism under United States political controlA third and increasingly persuasive characterisation views the Board of Peace as a coalition-based mechanism operating primarily through political coordination rather than legal delegation. Structural features attributed to the Board—such as chair-centred authority, discretionary appointment of executive organs, differentiated membership status tied to financial contribution, and limited transparency—align more closely with ad hoc coalitions than with orthodox international organizations.

From a legal perspective, this design points toward a functional arrangement whose acts are attributable to participating states rather than to an autonomous international person. In such cases, international law evaluates conduct through the lens of state responsibility, consent, and non-intervention, not through institutional competence. The Board’s decisions would have no inherent binding force and could not lawfully displace existing obligations under the UN Charter or other peremptory norms.

This coalition-based characterisation significantly constrains the Board’s legal authority. Its capacity to engage in territorial administration, security governance, or binding coordination would depend entirely on valid consent or explicit UN authorisation, neither of which can be presumed from institutional rhetoric or political sponsorship alone (De Wet, 2004).

2.3 Why classification mattersThe legal classification of the Board of Peace is not a technical exercise; it determines the entire framework of rights, obligations, and accountability applicable to its actions. Classification affects whether the Board possesses international legal personality or merely reflects the aggregated will of participating states. It governs entitlement to privileges and immunities, the attribution of conduct, and the allocation of international responsibility for potential violations of international humanitarian or human rights law.

Classification also determines institutional capacity. Only entities with recognised legal personality can conclude international agreements, administer territory in their own name, or appear as subjects capable of bearing claims. Where classification fails, such functions revert to states or to the United Nations, and legal responsibility follows accordingly.

Finally, classification shapes systemic legitimacy. An entity mischaracterised as an international institution may appear to “speak” for the international community without lawful authority, eroding the coherence of the Charter-based order. International law tolerates flexibility, but it does not permit ambiguity to substitute for authority. Understanding, in legal terms, what the Board of Peace is is therefore a prerequisite to assessing what it may lawfully do.

3. Claimed Legal Basis: The UN Charter System and Its Limits3.1 The Charter architecture for peace and securityThe United Nations Charter establishes a centralised legal architecture for the maintenance of international peace and security. Article 24 assigns the Security Council “primary responsibility” in this field, a formulation that is both functional and constitutional. It reflects a deliberate concentration of coercive authority in a single organ, designed to prevent fragmentation, competitive enforcement, and unilateralism in matters involving the use of force or international security governance (United Nations, 1945).

The Charter equips the Security Council with a graduated set of legal tools. Under Chapter VI, the Council may investigate disputes, recommend procedures, or propose terms of settlement. These acts are non-binding but carry significant political and legal weight, particularly when they frame disputes within the Charter’s normative language. Under Chapter VII, the Council may determine the existence of a threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or act of aggression, and adopt binding decisions requiring compliance by all UN Member States. These decisions may include economic sanctions, arms embargoes, and, where necessary, the authorisation of force.

Peace operations occupy an intermediate and historically evolving space within this framework. Although not explicitly mentioned in the Charter, they have developed as a pragmatic instrument grounded in Security Council authority, host-state consent, and limited use of force. Even the most expansive modern peace operations remain legally anchored in Council mandates that define objectives, geographic scope, duration, and reporting obligations. The Council does not merely initiate such operations; it retains legal and political oversight through mandate renewals, modifications, and termination (Gray, 2018).

This architecture reflects a core Charter principle: peace and security functions involving coercion or governance are not freely transferable. Authority flows from the Charter to the Council and, only through explicit legal acts, to subsidiary organs or authorised mechanisms. Any claim that a body such as the Board of Peace operates within the Charter system must therefore be tested against this allocation of authority.

3.2 Can the Security Council “create” or “recognise” external bodies?The Security Council possesses the power to establish subsidiary organs as necessary for the performance of its functions. These bodies are legally embedded within the UN system and derive their authority directly from the Charter. Their mandates, powers, and limits are defined by Council resolutions, and their acts are attributable to the United Nations as an international organisation.

This power, however, is distinct from the Council’s ability to endorse or cooperate with non-UN entities. The Council has, on occasion, welcomed the efforts of regional organisations, ad hoc coalitions, or transitional arrangements created outside the UN framework. Such endorsement may confer political legitimacy and, in limited circumstances, a degree of legal relevance. It does not, however, transform an external body into a UN organ nor does it confer unlimited authority.

The doctrinal distinction is critical. Subsidiary organs operate under direct UN control and are subject to internal accountability mechanisms, including reporting obligations and legal constraints arising from the UN’s international personality. External entities, even when referenced positively in Security Council resolutions, remain legally separate. Their authority continues to depend on their own legal basis—typically consent or treaty—and on strict adherence to the terms of the Council’s endorsement (De Wet, 2004).

Endorsement without mandate specificity risks blurring this boundary. International law does not support the notion that the Security Council can outsource its primary responsibility wholesale to a structurally independent body without retaining oversight. Delegation, where permitted, must remain bounded, reviewable, and revocable. Any interpretation suggesting otherwise would undermine the Charter’s institutional balance and dilute the Council’s accountability for peace and security outcomes.

3.3 Time-limited and situation-limited authorisationsA recurring feature of lawful Security Council action is temporal and contextual limitation. Mandates for peace operations, sanctions regimes, and transitional administrations are typically framed as responses to a specific situation and are subject to regular review. This practice reflects a fundamental legal logic: exceptional authority must remain exceptional.

Where a mandate is explicitly confined to a particular territory and period—such as post-conflict Gaza for a defined transitional phase—its legal justification rests on necessity and proportionality. The Council assesses whether the measure remains required to address the identified threat to peace. Expansion beyond that scope, absent a new determination and authorisation, lacks a Charter basis.

Tension arises when an entity authorised for a narrow task adopts or promotes a charter claiming broader or even global competence. Such claims cannot be reconciled with the situational logic of Chapter VII. A body may not lawfully convert a limited Security Council mandate into a standing institutional role applicable to unrelated conflicts. Doing so would amount to mandate self-extension, a concept incompatible with the Charter’s distribution of authority and with established Council practice (Farrall and Charlesworth, 2019).

The distinction is therefore doctrinal rather than rhetorical. A Gaza-specific authorisation may legitimise narrowly defined administrative or coordination functions. It does not support claims of permanence, replicability, or global peace governance absent fresh legal acts by the Security Council or valid consent by affected states.

3.4 Consent as a baseline legality filterOutside the scope of a valid Chapter VII mandate, international law treats consent as a central condition for lawful external involvement in a state or territory. Sovereignty and the principle of non-intervention prohibit foreign entities from exercising governmental or security functions without the consent of the relevant sovereign or a lawfully recognised representative authority (United Nations, 1945).

Consent must meet substantive criteria. It must be given freely, by an authority capable of representing the population concerned, and within the bounds of international law. Consent extracted under coercion, or granted by an entity lacking representative legitimacy, is legally defective. Moreover, consent is inherently limited; it authorises specific acts for defined purposes and does not permit open-ended governance or security control.

In the context of contested territories, the consent requirement becomes especially stringent. Where statehood, occupation, or representation is disputed, international law demands heightened caution. Absent clear Security Council authorisation, any attempt by the Board of Peace to operate administratively or militarily would face a presumption of illegality if valid consent cannot be demonstrated. The legal risk is not abstract: breach of sovereignty and non-intervention carries consequences for state responsibility and for the legitimacy of any resulting governance arrangements.

Consent thus operates as a baseline legality filter. It cannot transform a politically appealing initiative into a lawful one, but its absence is often decisive. For the Board of Peace, claims of Charter compatibility ultimately collapse if neither a robust Chapter VII mandate nor valid consent exists to support its operations.

4. Treaty Law Constraints: Why “Charters” Do Not Magically Bind the World4.1 The third-state rule (pacta tertiis nec nocent nec prosunt)One of the clearest limits imposed by international law on institutional ambition is the rule that treaties neither impose obligations nor confer rights upon third states without their consent. Codified in Article 34 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, this principle reflects a foundational aspect of state sovereignty: legal obligations arise from consent, not from institutional design or political influence (Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969; Aust, 2013).

Applied to the Board of Peace, this doctrine directly challenges claims of a “global mandate” or general authority to intervene in peace and security matters beyond the circle of participating states. Even if a group of states were to conclude a charter establishing the Board and empowering it to act in multiple conflict settings, such provisions would have no binding legal effect on non-participating states or on populations subject to the Board’s proposed activities. At most, the charter would regulate internal relations among its parties.

The third-state rule also limits any attempt to frame the Board of Peace as a substitute for collective security mechanisms. International law does not recognise self-declared universality. Authority to affect the rights or obligations of others must stem either from their consent or from a valid Security Council decision adopted under the Charter. Absent these conditions, assertions of external competence remain legally ineffective, regardless of the urgency or moral framing attached to them.

This constraint is particularly salient where the Board of Peace is presented as a reusable model applicable across regions. Without individualised consent or renewed legal authorisation for each context, such claims collide with the basic structure of treaty law. The legal order resists the conversion of contractual arrangements into general norms through institutional aspiration alone.

4.2 Membership by invitation and “pay-for-permanence”The internal membership rules of an institution are often treated as a matter of political discretion. Treaty law, however, does not treat all membership arrangements as normatively neutral. Where governance influence is explicitly linked to financial contribution or selectively granted permanent status, deeper doctrinal concerns arise.

The principle of sovereign equality, enshrined in Article 2(1) of the UN Charter, operates as an organising norm of the international legal order. It does not require identical influence in every institutional setting, but it does set limits on arrangements that entrench hierarchy without a clear legal or functional justification. In established international organisations, differentiated membership is typically justified by objective criteria embedded in a constitutional framework accepted by the membership as a whole (Crawford, 2019).

By contrast, a structure in which permanent or enhanced governance roles are acquired through financial contribution risks creating a transactional model of authority. From a legal perspective, this raises two concerns. First, it weakens claims of representativeness, particularly where decisions affect populations or territories not represented within the funding coalition. Second, it increases the risk of institutional capture, where decision-making reflects donor preferences rather than collectively defined legal mandates (Klabbers, 2015).

In the context of the Board of Peace, invitation-based participation combined with monetised permanence reinforces the perception that the body operates as a coalition of the willing rather than as a public international institution. Such a design may be politically expedient, but it complicates any attempt to ground the Board’s authority in general international law. Legitimacy deficits are not merely reputational; they affect the legal credibility of decisions taken and the willingness of third states to recognise or cooperate with them.

4.3 Legal effects of ratification and domestic approvalIf the Board of Peace charter is framed as a treaty, its legal existence and effects depend on compliance with the standard rules of treaty formation. Signature alone does not normally create binding obligations. Under international law, a treaty enters into force only in accordance with its own provisions, typically following ratification or equivalent domestic approval by participating states (Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969).

Domestic constitutional requirements play a decisive role at this stage. States may require parliamentary approval, legislative incorporation, or other formal acts before international commitments become legally binding. Until these processes are completed, political commitments expressed through declarations or provisional arrangements remain legally fragile. They may generate expectations of good faith but do not confer full treaty status or institutional authority (Aust, 2013).

This distinction matters for the Board of Peace because interim political support is often conflated with legal endorsement. Operating an institution, appointing officials, or announcing mandates before the charter has entered into force creates a gap between political action and legal foundation. International law does not prohibit preparatory steps, but it does not treat them as a substitute for valid consent.

The limits of interim commitments become even more pronounced where the Board claims authority to act externally. Without a treaty in force, there is no legal personality to invoke, no institutional capacity to rely upon, and no basis for privileges, immunities, or responsibility attribution. Ratification is therefore not a technicality; it is the legal threshold separating political initiative from juridically cognisable institution.

In sum, treaty law imposes structural constraints that institutional rhetoric cannot overcome. Charters do not bind the world by proclamation, funding, or urgency. They bind only through consent, formalisation, and respect for the legal order within which they seek to operate.

5. International Legal Personality: Capacity, Recognition, and Fiction5.1 Legal personality in international law (functional approach)International legal personality is not an all-or-nothing attribute conferred by label or aspiration. In international law, personality is determined through a functional analysis that examines whether an entity requires legal capacity to perform the tasks assigned to it. This approach was articulated authoritatively by the International Court of Justice in Reparation for Injuries Suffered in the Service of the United Nations, where the Court held that the United Nations possessed international legal personality because it was intended to exercise functions that could not be effectively performed without it (ICJ, 1949).

The functional logic developed by the Court rejects formalism. An entity does not become a subject of international law simply because its founders declare it to be so. Instead, personality is inferred from necessity: the ability to enter into agreements, own property, bring claims, or enjoy privileges and immunities must be essential to the discharge of the entity’s mandate. This doctrine has been consistently applied to international organisations and, more cautiously, to other institutional arrangements performing public functions (Klabbers, 2015; Schermers and Blokker, 2018).

Applied to the Board of Peace, the functional test requires close scrutiny of its claimed tasks. If the Board is expected to administer territory, coordinate security forces, manage humanitarian assistance, or negotiate binding arrangements, some degree of legal capacity would be practically necessary. However, functional necessity does not automatically resolve the source or scope of that capacity. International law distinguishes between the existence of capacity and the legality of its exercise. An entity may require capacity to operate, yet still lack a lawful basis to possess it.

5.2 “International legal personality” by Security Council languageProposals relating to the Board of Peace have relied in part on the use of Security Council language describing it as a “transitional administration with international legal personality” in the Gaza context. The legal significance of such language depends on whether it is understood as constitutive or declaratory.

A constitutive interpretation would suggest that the Security Council, by virtue of its Chapter VII powers, can create international legal personality through resolution alone. While the Council has established subsidiary organs with legal capacity, this capacity is derivative and embedded within the UN system. It does not generally create autonomous international persons capable of acting independently of the Council’s authority. To read Council language as constitutive in this stronger sense would stretch established doctrine and risk collapsing the distinction between UN organs and external entities (De Wet, 2004).

A declaratory interpretation is more consistent with international practice. Under this view, the Council recognises that an entity requires limited legal capacity to perform specific tasks within a defined mandate. The recognition does not create a general legal personality but acknowledges functional capacity for the duration and scope of the authorised activity. Historical examples of transitional administrations support this reading, as their personality has been treated as instrumental and circumscribed rather than autonomous or permanent (Gray, 2018).

In the Gaza context, Security Council language referencing legal personality is best understood as declaratory. It signals that certain administrative or coordination functions may necessitate limited capacity, such as contracting for services or liaising with international actors. It does not confer an open-ended institutional status nor does it legitimise expansion beyond the authorised mandate. Any broader reading would contradict the Council’s practice of maintaining close supervision over transitional arrangements.

5.3 Capacity versus legitimacyThe distinction between capacity and legitimacy is central to evaluating the Board of Peace. Capacity addresses a technical legal question: does the entity possess the ability to act in international law? Legitimacy addresses a normative one: should those acts be regarded as lawful and authoritative within the international legal order?

An entity may possess functional capacity yet act unlawfully. Legal personality does not immunise conduct from scrutiny under peremptory norms, the principle of self-determination, or the structural constraints of the UN Charter. Compliance with international humanitarian law, international human rights law, and the prohibition of acquisition of territory by force remains mandatory regardless of institutional form (Crawford, 2019).

For the Board of Peace, this distinction has practical consequences. Even if limited legal personality were recognised for transitional purposes, this would not resolve questions concerning representation of the affected population, respect for self-determination, or compatibility with the Charter’s allocation of authority. Recognition of capacity answers how the Board could act; it does not justify why others should accept its actions as lawful or binding.

International law thus resists the conflation of functional necessity with normative legitimacy. The danger of treating capacity as a proxy for authority lies in normalising arrangements that operate effectively while eroding the foundational principles of the legal order. Any assessment of the Board of Peace must therefore keep these questions analytically separate, recognising that legal personality is a means, not an endorsement.

6. The Gaza Mandate as a Stress Test for International Law6.1 Gaza’s status and the law applicableAny assessment of a Gaza-specific mandate must begin with the legal status of the territory and the applicable body of law as of 2026. Despite shifts in military posture, control modalities, and governance proposals, Gaza continues to be analysed in international legal debate through the lens of occupation and effective control. The prevailing doctrinal view is that occupation law applies where a foreign power exercises, or is capable of exercising, decisive authority over key governmental functions, even in the absence of continuous physical presence across the entire territory (Ben-Naftali, Gross and Michaeli, 2023; Milanovic, 2024).

Control over borders, population registry, airspace, maritime access, and the flow of goods and services remains legally relevant. These elements sustain arguments that Gaza is not a legal vacuum but a territory subject to layered legal regimes. The Fourth Geneva Convention and the Hague Regulations continue to impose constraints on security measures, administrative restructuring, and the treatment of civilians. Any governance arrangement introduced under the label of “transition” must therefore operate within these constraints rather than displacing them.

Alongside occupation law, international humanitarian law governs the conduct of hostilities and the protection of civilians, while international human rights law applies concurrently, particularly in areas where public authority is exercised over individuals. The interaction between these regimes is not discretionary. A transitional administration or external governance mechanism does not suspend human rights obligations; it inherits them to the extent that it exercises public power (Alston and Knuckey, 2022). The Gaza mandate thus functions as a legal stress test because it exposes the difficulty of reconciling claims of emergency governance with enduring obligations rooted in occupation, humanitarian protection, and human rights norms.

6.2 International administration in comparative perspectiveInternational law does not lack precedents for the external administration of territory. United Nations transitional administrations in Kosovo and East Timor are frequently cited as comparators, not because they were flawless, but because they illustrate the minimum institutional features that international law has previously tolerated.

These administrations were characterised by a clear chain of command linking local executive authority to the Security Council through the Secretary-General. Decision-making authority was centralised and formally accountable within the UN system, even when operational discretion was broad. Mandates were explicitly time-bound and purpose-specific, oriented toward a defined political end-state such as independence, constitutional self-government, or transfer of authority to local institutions (Chesterman, 2005; Stahn, 2018).

Accountability mechanisms, though often criticised as insufficient, were nonetheless identifiable. The administrations were subject to reporting obligations, internal review structures, and at least indirect political oversight by UN organs. This institutional embedding mattered legally: it grounded extraordinary authority in a recognised constitutional framework rather than in ad hoc arrangements.

By contrast, governance models proposed for Gaza in 2025–2026 depart from these precedents in significant ways. The absence of a clear UN chain of command, the fragmentation of authority across multiple bodies, and the lack of a defined end-state complicate efforts to situate such arrangements within accepted international practice. Comparison does not establish illegality by itself, but it highlights how far current proposals stretch the margins of what international law has previously accepted. 6.3 Governance architecture described in the materialsThe governance architecture described across policy documents and analytical sources is markedly multi-layered and fragmented. At the apex sits the Board of Peace, framed as a strategic authority. Beneath it operates an Executive Board with appointment powers and agenda-setting functions. A Gaza-specific Executive Board or administrative body is envisaged to manage day-to-day governance, supported by a “National Committee” composed of technocrats rather than politically representative actors. Parallel to these civilian structures, an international stabilisation force is proposed to perform security functions.

From a legal perspective, this architecture generates several risks. Fragmented authority blurs responsibility. When decision-making power is distributed across bodies with overlapping mandates, it becomes difficult to determine who is legally accountable for specific acts or omissions. International law requires clarity for attribution of conduct, particularly where coercive power or administrative control affects civilian populations.

Weak transparency compounds this problem. Appointment mechanisms dominated by external actors, limited disclosure of decision-making processes, and the absence of public reasoning undermine the procedural legitimacy of governance acts. Transparency is not merely a governance virtue; it is a legal safeguard that enables scrutiny, responsibility, and remedies.

Most critically, unclear command responsibility in relation to the stabilisation force raises acute legal concerns. Where military or security forces operate without a clearly defined command structure anchored in international law, the risk of responsibility gaps increases. Attribution of violations, compliance with international humanitarian law, and the availability of remedies all depend on knowing who commands whom and under what legal authority (Crawford, 2019). The proposed Gaza governance structure, as described, struggles to meet this standard.

6.4 Self-determination and local participationInternational law treats self-determination as a continuing entitlement, not a reward contingent on external approval. Any interim administration of territory must be directed toward enabling genuine self-government within a reasonable time frame. This requirement applies irrespective of the administrative label attached to the arrangement (Cassese, 1995; Crawford, 2019).

Applied to Gaza, the self-determination standard exposes a central tension in the proposed mandate. Reports of limited agency for Palestinian decision-makers, reliance on externally appointed technocratic bodies, and conditionality structures tying political advancement to security or governance benchmarks raise serious legal questions. While international law permits temporary external assistance or administration, it does not authorise indefinite substitution of local political authority.

Conditionality becomes legally problematic when it effectively subordinates self-determination to externally defined criteria without a clear pathway for political choice by the affected population. Exclusion of representative Palestinian actors, even under the justification of stability or neutrality, risks transforming transitional governance into prolonged external control.

The Gaza mandate thus illustrates the limits of functional governance divorced from political rights. Efficiency cannot replace legitimacy, and stability cannot lawfully be pursued at the expense of self-determination. International law demands that interim arrangements serve as bridges to self-government, not as holding structures that normalise external dominance under a different name.

7. Use of Force, Peace Operations, and the “Stabilisation Force” Question7.1 When is a force lawful?International law permits the use of force only within narrowly defined legal bases. Outside these exceptions, the deployment of armed force constitutes a violation of the prohibition enshrined in Article 2(4) of the UN Charter, a cornerstone norm of the post-1945 international legal order (United Nations, 1945; Gray, 2018).

The first lawful basis is valid host-state consent. Consent must be given by an authority capable of representing the state or territory concerned and must be free, informed, and limited in scope. Consent does not legalise all conduct; it authorises only what is explicitly or implicitly agreed and remains constrained by international humanitarian law and international human rights law. In contested territories such as Gaza, identifying a legally valid consenting authority is particularly complex, rendering reliance on consent legally precarious.

The second basis is Security Council authorisation under Chapter VII of the UN Charter. Such authorisation may permit enforcement action, including the use of force, where the Council determines a threat to international peace and security. Crucially, the Council must define the mandate, objectives, and limits of any authorised force. Open-ended or ambiguous authorisations are inconsistent with established Council practice, which emphasises specificity and ongoing oversight (Farrall and Charlesworth, 2019).

The third basis is self-defence, individual or collective, under Article 51 of the Charter. This justification is subject to strict conditions of necessity and proportionality and is temporally limited to situations of armed attack. Self-defence cannot serve as a standing legal basis for stabilisation or governance operations, nor can it justify broad security mandates disconnected from an immediate defensive purpose (Crawford, 2019).

These bases must be distinguished from the conceptual categories of peacekeeping and peace enforcement. Peacekeeping, as developed in UN practice, rests on consent, impartiality, and limited use of force, typically restricted to self-defence and defence of the mandate. Peace enforcement, by contrast, involves coercive force authorised by the Security Council without the full consent of the parties. The legal distinction is fundamental: peacekeeping presupposes a permissive environment, while peace enforcement operates under exceptional authority and heightened legal scrutiny. Blurring these categories obscures the applicable legal regime and risks unlawful use of force.

7.2 The “International Stabilization Force” and command structureProposals for an “International Stabilization Force” operating in Gaza raise acute legal concerns linked to command and control. International law attaches decisive importance to clear reporting lines and mandate definition for any multinational force exercising security functions. These elements determine not only operational effectiveness but also legal accountability.

Where command authority is fragmented between an external board, an executive body, contributing states, and potentially private contractors, attribution of conduct becomes uncertain. The law of state responsibility and the responsibility of international organisations both rely on identifiable chains of command to assign legal consequences for violations of international humanitarian law or human rights law (Crawford, 2019). Ambiguity in command structure risks producing responsibility gaps, leaving victims without effective remedies.

Mandate clarity is equally significant. A force tasked simultaneously with stabilisation, counter-insurgency, protection of civilians, and support for governance exceeds the traditional boundaries of peacekeeping and begins to resemble enforcement action. Without explicit Security Council authorisation or valid consent, such a mandate lacks a secure legal foundation. Even where authorisation exists, international law requires that the scope, duration, and permissible use of force be precisely articulated.

In the Gaza context, the absence of a unified UN chain of command distinguishes the proposed stabilisation force from prior UN-led operations. This structural separation weakens claims that the force operates within the established peace operations framework and strengthens the view that it functions as a coalition security instrument, subject to stricter legality tests and heightened responsibility exposure.

7.3 Humanitarian assistance and militarisation risksHumanitarian assistance is governed by well-established operational principles: humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence. These principles are not aspirational; they are legal and practical constraints designed to ensure access to populations in need and protection for humanitarian actors (ICRC, 2015; Alston and Knuckey, 2022).

Militarised delivery models, particularly those integrated into stabilisation or security operations, place these principles under strain. When humanitarian aid is delivered by or alongside armed forces, it risks being perceived as part of a political or military strategy. This perception undermines neutrality and impartiality, exposing aid workers and beneficiaries to increased security risks and potentially restricting access to vulnerable populations.

In Gaza, where humanitarian needs are acute and trust in external actors is fragile, the conflation of security and assistance functions is especially problematic. International law does not prohibit military support to humanitarian operations, but it requires clear functional separation. Aid must not become conditional on compliance with security objectives or governance benchmarks imposed by external authorities.

The legal implication is direct: where humanitarian assistance is subordinated to stabilisation goals, the administering authority may incur responsibility for violating humanitarian principles and, by extension, the rights of the civilian population. The challenge for any proposed stabilisation force is therefore not only to maintain security but to do so without eroding the legal and ethical foundations of humanitarian action.

8. Responsibility and Attribution: Who Answers for Violations? 8.1 Attribution of conduct in hybrid structuresOne of the most legally problematic features of the Board of Peace model lies in the attribution of conduct. International law assigns responsibility based on control, authority, and institutional linkage, not on political narratives or organisational labels. Hybrid governance structures—where authority is dispersed across boards, states, appointed officials, and armed forces—create acute attribution challenges that international law addresses through established but demanding frameworks.

Acts performed by organs of the Board of Peace would, if the Board were recognised as possessing international legal personality, be attributable to the organisation itself. Under the law on the responsibility of international organisations, conduct of organs or agents acting in an official capacity engages the organisation’s responsibility, provided those acts fall within the scope of their functions (ILC, 2011). If the Board lacks legal personality, however, such acts revert to attribution to the states that established, control, or direct the body.

Contributing states remain legally exposed even where actions are channelled through an institutional framework. International law does not permit states to shield themselves from responsibility by acting collectively or through intermediaries. Where states exercise effective control over decision-making, financing, appointments, or operational directives, their responsibility may be engaged alongside or instead of any institutional attribution (Crawford, 2019).

The position of individuals and officials, whether seconded by states or externally appointed, further complicates attribution. Officials do not operate in a legal vacuum. Their conduct is attributed to the entity under whose authority they act, provided that authority is legally constituted. Where appointment chains are opaque or authority is contested, attribution becomes unstable, increasing the risk that responsibility is deflected rather than assumed.

The most acute difficulties arise with armed forces operating under multinational command. International jurisprudence and doctrine emphasise effective control as the decisive criterion. If forces remain under national command, their conduct is attributable to the contributing state. If operational control is transferred to an international entity, attribution may shift, wholly or partially, to that entity (ILC, 2011; Nollkaemper and Plakokefalos, 2014). Ambiguous command structures, as envisaged in stabilisation proposals linked to the Board of Peace, risk creating responsibility gaps where violations occur but no actor accepts legal ownership.

International law tolerates complexity but not evasion. Hybrid structures must therefore be assessed against attribution standards designed to prevent diffusion of responsibility through institutional fragmentation.

8.2 Due diligence and positive obligationsA recurrent claim in transitional governance debates is that external administrators are not bound by the full spectrum of obligations applicable to occupiers or sovereign governments. This position has no support in contemporary international law. The absence of a formal occupation status does not immunise an authority exercising public power from legal obligations.

International human rights law imposes positive obligations on any actor exercising governmental functions, including duties to protect life, ensure humane treatment, prevent discrimination, and provide access to remedies. These obligations arise from control over persons and territory, not from formal sovereignty (Alston and Knuckey, 2022). An administrator who regulates movement, oversees security, controls access to essential services, or influences governance outcomes assumes corresponding responsibilities.

The duty of due diligence is central. Authorities must take reasonable measures to prevent foreseeable harm caused by their own agents or by third parties operating within the sphere of their control. Failure to do so engages responsibility even where the harm is inflicted indirectly. In Gaza, where civilian vulnerability is extreme, due diligence obligations acquire heightened significance.

Claims that the Board of Peace is merely a coordinating or advisory body do not negate these duties if its decisions materially shape security operations, humanitarian access, or governance outcomes. International law focuses on effect rather than description. Where influence becomes determinative, responsibility follows.

8.3 Accountability gapsThe materials underlying the Board of Peace proposals consistently reveal a structural accountability deficit. Unlike UN-led administrations, which at least operate within a recognisable system of institutional oversight, the Board model lacks clear mechanisms for legal review and supervision.

Judicial review appears weak or absent. There is no clearly articulated forum—international or domestic—where affected individuals could challenge administrative decisions, security measures, or rights violations attributable to the Board or its associated bodies. Without such mechanisms, the rule-of-law dimension of governance is severely compromised.

Supervision by United Nations organs is similarly unclear. The absence of a defined reporting relationship to the Security Council or the Secretary-General removes a critical layer of political and legal accountability that has historically mitigated, albeit imperfectly, the excesses of international administrations (Stahn, 2018).

Most critically, remedies for affected civilians remain uncertain. International law requires not only the avoidance of violations but also access to effective remedies when violations occur. Where responsibility is diffused across boards, states, contractors, and forces, victims may be left without a viable respondent. This outcome contradicts fundamental principles of international responsibility and undermines the credibility of any governance arrangement claiming legal legitimacy.

Responsibility without accountability is not a neutral omission; it is a structural flaw. For the Board of Peace, unresolved attribution and accountability gaps represent one of the most serious obstacles to its acceptance within the international legal order.

9. Privileges, Immunities, and the Rule-of-Law Paradox9.1 Immunities are functional, not decorativePrivileges and immunities in international law are not symbols of status or political favour. They are functional legal tools designed to ensure that international actors can perform their assigned tasks independently and without undue interference by domestic authorities. This functional rationale has been consistently affirmed in doctrine and jurisprudence, particularly in relation to international organisations whose activities could otherwise be paralysed by national legal processes (Schermers and Blokker, 2018; Klabbers, 2015).

At the same time, international law recognises a structural tension inherent in immunities. While they protect institutional independence, they also restrict access to domestic courts for individuals affected by the organisation’s conduct. Immunities, therefore, aggravate accountability gaps unless they are counterbalanced by alternative mechanisms of responsibility, such as internal claims commissions, ombudspersons, or international review procedures. Where such alternatives are absent or ineffective, immunity risks undermining the rule of law rather than serving it (Stahn, 2018).

This paradox has been most visible in the practice of United Nations peace operations and administrations, where functional immunity has shielded the organisation from domestic jurisdiction while internal accountability mechanisms have often proven insufficient. International law has not abandoned immunities in response, but it increasingly treats their legitimacy as contingent on the availability of meaningful remedies. Immunity without accountability is no longer regarded as normatively neutral.

For the Board of Peace, this functional logic is decisive. Any claim to immunity must be justified by necessity and accompanied by credible accountability arrangements. Without such a balance, immunity would operate not as a safeguard of independent function but as a barrier to legal responsibility.

9.2 Does the Board of Peace qualify for immunities?Whether the Board of Peace qualifies for privileges and immunities depends on a sequence of doctrinal questions grounded in both international and domestic law. Immunity does not arise automatically from political endorsement or operational importance.

The first question is whether the Board of Peace constitutes an international organisation under domestic law. Domestic courts typically assess this by examining whether the entity was created by an international agreement, possesses institutional autonomy, and is intended to operate independently of its member states. Absent clear recognition in domestic legal orders, claims to immunity are unlikely to succeed.

The second question concerns the existence of a treaty or other conferral mechanism granting immunities. For most international organisations, privileges and immunities are grounded in a constituent treaty or a separate immunities agreement binding on the host state. Without such an instrument, immunity claims lack a legal foundation. Political declarations or references in policy documents do not substitute for binding legal commitments (Aust, 2013).

The third question is whether there is a host-state agreement explicitly conferring immunities and defining their scope. Host-state agreements are critical because immunities operate primarily at the domestic level. In their absence, domestic courts retain jurisdiction, and the organisation remains subject to national law.

Contrasting the Board of Peace with the United Nations highlights the gap. The UN’s legal capacity and privileges and immunities are explicitly recognised in the UN Charter and elaborated in a dedicated convention. This framework establishes a uniform, treaty-based regime accepted by member states and accompanied—at least in principle—by internal accountability mechanisms. The Board of Peace lacks an equivalent constitutional foundation.

Without recognition as an international organisation, without a binding treaty conferring immunities, and without host-state agreements establishing their scope, the Board of Peace cannot plausibly claim the protections enjoyed by UN organs. Any assertion of immunity would therefore rest on legal fiction rather than doctrine.

The rule-of-law paradox is thus acute. If the Board of Peace seeks immunity without satisfying the legal prerequisites or providing alternative remedies, it risks replicating the accountability failures associated with international administration while lacking the constitutional safeguards that partially legitimise them. International law does not prohibit immunities, but it conditions them on legality, necessity, and accountability—conditions the Board of Peace has yet to meet.

Also Read

10. Systemic Implications: A Parallel Peace-and-Security Order?10.1 Encroachment on UN institutional designThe Board of Peace proposal is not only a question of legality in a single theatre; it tests whether the UN Charter’s constitutional design for peace and security can be functionally bypassed. The Charter centralises coercive authority by assigning the Security Council primary responsibility for international peace and security and by restricting unilateral or coalition uses of force (United Nations, 1945). The practical question, therefore, is whether the Board of Peace operates as a complementary mechanism within this design or as a rival architecture that shifts the locus of authority away from the UN system.

A complementary mechanism would be legally plausible only under narrow conditions. It would need to be consent-based or explicitly authorised by the Security Council for a defined situation, with clear limitations on mandate, duration, and permissible functions. In such a configuration, the Board might resemble a coordination platform that supports reconstruction, humanitarian logistics, or technical governance assistance without claiming to replace Charter-based processes.

A rival architecture emerges when the Board claims standing competence to manage conflicts, administer territory, or direct security operations without being embedded in the Council’s mandate and oversight structure. Even where the Security Council is politically deadlocked, institutional paralysis does not create a legal licence for states to construct parallel enforcement arrangements and treat them as if they carry collective authority. The Charter was designed precisely to avoid decentralised enforcement systems that convert power into legality by coalition formation. If the Board of Peace is framed as an alternative to UN authority rather than a delegated instrument under it, it risks eroding the Charter’s centralisation logic and normalising the idea that peace and security governance can be outsourced to selective groupings.

10.2 “Selective multilateralism” and legitimacyThe legitimacy problem raised by the Board of Peace is not simply that membership may be limited. Many international institutions have restricted membership. The core issue is the combination of selective participation with a governance design that concentrates authority, differentiates status through financial contribution, and permits leadership-driven institutional control.

Representativeness matters in peace-and-security governance because the decisions taken often affect third states and, more directly, populations subject to security measures and administrative decisions. Where participation is by invitation and governance influence is tied to major funding contributions, the institution begins to resemble a transactional coalition rather than a public multilateral body. This risks a legitimacy deficit that is structural: the entity’s authority is perceived as purchased rather than delegated through broadly accepted legal procedures (Klabbers, 2015).

Inclusivity also matters as a functional legal safeguard. Broader participation increases scrutiny, reduces the risk of capture, and enhances compliance incentives. A model that concentrates agenda control and dismissal powers in leadership structures increases the risk that governance becomes personalised rather than institutional. Such leader-centric design undermines the normative claim that decisions represent collective judgment rather than the strategic preferences of dominant actors. The legitimacy costs are not abstract; they shape cooperation, compliance, and the credibility of any legal claims advanced by the institution.

The Board of Peace model, as described in policy analysis, is therefore best understood as “selective multilateralism”: multilateral in form but narrow in representation and transactional in influence. That combination weakens any attempt to portray it as a neutral institutional substitute for Charter-based multilateralism (Schermers and Blokker, 2018).

10.3 Precedent riskThe most serious systemic consequence is precedent. International law often develops through practice justified by necessity and later treated as a template. If Gaza becomes an accepted “experiment” in external governance under a loosely accountable, non-UN institutional design, it can be invoked to justify similar arrangements elsewhere.

The precedent risk operates in two stages. First, an ad hoc administration is established with claims of urgency and stabilisation. Second, the exceptional arrangement becomes normalised and cited as evidence that parallel governance mechanisms are permissible when the Security Council is divided or when political consensus is absent. This creates a pathway for incremental erosion of UN-centred authority: each new crisis becomes a justification for constructing a bespoke administration that lacks UN supervision, clear accountability mechanisms, and robust safeguards for self-determination.

Such a trajectory would weaken the Charter system not through formal amendment but through functional displacement. The danger is not only institutional competition; it is normative slippage. Once parallel administrations are treated as acceptable substitutes for UN-authorised mechanisms, the legal order risks reverting to a hierarchy of influence where governance authority follows power and finance rather than universal legal constraints. International law can accommodate innovation, but it cannot sustain a peace-and-security architecture in which accountability and representativeness are optional features of crisis management.

This is why the Board of Peace must be evaluated as more than a Gaza proposal. It is a test case for whether the Charter’s central premise—collective security under a unified legal framework—can withstand the growing appeal of selective, leader-driven alternatives.

11. Doctrinal Conclusions and Criteria for Lawful Design11.1 What the law permits (minimum conditions)

International law does not prohibit innovative mechanisms for peace support or post-conflict governance. It does, however, impose minimum structural conditions that must be met before such mechanisms can operate lawfully. These conditions are cumulative rather than optional.

First, there must be mandate clarity and a valid legal basis. Authority must rest either on explicit Security Council authorisation adopted in accordance with the UN Charter or on valid consent given by a sovereign or lawfully representative authority. Political endorsement, moral urgency, or institutional branding cannot substitute for a recognised legal foundation (United Nations, 1945; Gray, 2018).

Second, any exceptional governance authority must be strictly time-limited and directed toward a defined end-state. Transitional arrangements are lawful only when they are genuinely transitional. International practice tolerates temporary deviation from ordinary governance only where there is a clear pathway toward restoration or establishment of self-government. Open-ended or renewable mandates without political destination undermine this logic and risk unlawful entrenchment (Stahn, 2018).

Third, self-determination safeguards and meaningful local participation are indispensable. Interim governance must be oriented toward enabling political agency, not managing it indefinitely. Participation cannot be purely technocratic or consultative; it must allow affected populations to influence governance outcomes and future political status (Cassese, 1995; Crawford, 2019).

Fourth, transparent rulemaking and public reasons are required. Where external authorities exercise public power, international law increasingly demands reasoned decision-making, disclosure of governing norms, and procedural fairness. Transparency functions as a legal safeguard, enabling scrutiny, responsibility, and eventual remedies.

Fifth, accountability mechanisms must exist and be accessible. This includes complaints procedures, ombudspersons or equivalent oversight bodies, and some form of independent review. Immunity from domestic jurisdiction is tolerable only when alternative remedies are available and effective (Schermers and Blokker, 2018).

Finally, responsibility attribution and command clarity, particularly for any armed forces, are non-negotiable. International law requires clear chains of command and attribution to prevent responsibility gaps. Where coercive power is exercised, ambiguity itself becomes a source of illegality (Crawford, 2019).

11.2 What the law likely prohibits or renders ineffectiveInternational law draws a clear line against claims of general or global mandate unsupported by consent or Security Council authorisation. A charter concluded among a limited group of states cannot bind third states, authorise intervention, or confer governance authority beyond its parties. Assertions of global competence without a recognised legal basis are legally non-binding and, if operationalised, risk constituting unlawful interference in the affairs of other states or peoples (Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969; De Wet, 2004).

The law is equally sceptical of arrangements that conflate political necessity with legal authority. Governance mechanisms that operate through selective participation, monetised influence, or leader-centric control may function politically, but they lack the legal qualities required for sustained legitimacy. When such mechanisms attempt to exercise administrative or security functions without satisfying Charter-based requirements, they become legally unstable and exposed to responsibility claims.

Most critically, international law does not recognise functional success as a substitute for legality. Stability achieved through arrangements that bypass consent, accountability, or self-determination does not cure underlying legal defects. On the contrary, operational effectiveness without legal grounding magnifies the risk of systemic erosion of the international legal order.

11.3 The core doctrinal findingThe legality of the Board of Peace does not depend on its political appeal, strategic convenience, or perceived efficiency. It turns on authority, consent, mandate limitation, and accountability. International law permits temporary, narrowly tailored mechanisms operating within the UN Charter framework or grounded in valid consent. It does not permit parallel peace-and-security architectures that substitute selective governance for collective legal authority.

The more the Board of Peace presents itself as an alternative to the Charter system—rather than a delegated, constrained instrument within it—the more fragile its legal position becomes. What is at stake is not institutional innovation but constitutional coherence. International law can accommodate new tools, but it cannot sustain a peace-and-security order in which power precedes legality, and accountability is optional.

https://www.diplomacyandlaw.com/post/the-board-of-peace-vs-international-law

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 29 Jan 2026 - 9:57am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

8 hours 31 min ago

8 hours 43 min ago

8 hours 51 min ago

9 hours 37 min ago

11 hours 35 min ago

12 hours 10 min ago

12 hours 26 min ago

12 hours 43 min ago

17 hours 24 min ago

17 hours 33 min ago