Search

Recent comments

- sicko....

5 hours 44 min ago - brink...

6 hours 29 sec ago - gigafactory.....

7 hours 47 min ago - military heat....

8 hours 29 min ago - arseholic....

13 hours 13 min ago - cruelty....

14 hours 29 min ago - japan's gas....

15 hours 10 min ago - peacemonger....

16 hours 6 min ago - see also:

1 day 1 hour ago - calculus....

1 day 1 hour ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

defining freedom .....

Until last week Occupy Oakland took up about as much space in the national consciousness as Occupy Tulsa.

But then, last Wednesday, the Oakland Police Department tried to end the occupation in a violent clash that lead to the injury of Iraq war veteran Scott Olsen. As a result, Occupy Oakland saw an explosion of bodies and attention unseen at any camp elsewhere in the world.

The difference was dramatic to say the least. When police went into Oscar Grant Park last week there were, by the most generous estimates, about 2,000 people staying there. Yesterday's general strike drew 20,000 people according to the Occupy Oakland website. Oakland officials put that number far lower, but regardless, the showing was greater than any other protests in the country so far.

And it was more violent. Sixty to 70 people were arrested as black-clad and masked protesters wreaked havoc on the city, breaking windows and defacing buildings.

It's likely none of this would have happened without last week's strong show of police force, and the Soctt Olsen rallying cry. Those are two factors that are unlikely to go away as the protest movement goes on.

And then there are these factors that make Oakland a great occupation spot that aren't about to change either:

Demographics: It would be easy to say that because Oakland is has a 75 percent minority population that it's a hot-bed of civil disobedience and unrest. Oakland isn't divided by race so much as geography. Like the rest of America, the disparity of wealth in Oakland is stark, but it's also broken into two sections: "the hills" and "the flatlands." The hills house Oakland's affluent, about one-third the population, the remaining two-thirds lives in the flatlands.

There are about 50 neighborhoods in Oakland, many not distinct enough to be on a map, and getting around the city is a piece of cake. Oakland is rated the 10th most walkable city in 2011. Corralling protesters and keeping others out is more difficult here perhaps, than elsewhere.

Climate: Oakland has one of the most envied climates in the United States. Temperate and Mediterranean, its summers are dry and they lead to mild, moist winters. It's warmer in the winter than San Francisco across the bay and protesters here can expect average high temperatures of almost 64 degrees until December when high temps will hover around 60 degrees. Obviously, that means they don't face the 'what do we do in the winter?' question other occupations face.

Income: Black workers in Oakland make 60 cents less an hour than their white counterparts, and Latinos earn 47 cents on the dollar. Two in five residents are working poor and incomes have declined by 5 percent or almost $2,000 since before the recession, while the cost of living in the Bay area has continued to increase.

The wealth gap there is widening rapidly. The people of Oakland are living the issues behind the occupation every day.

And one more thing. They can make an impact. Yesterday they shut down the Port of Oakland, the fifth largest deepwater port in the country, and one of three major ports on the West Coast. It's even more important than San Francisco's port and can load any kind of transportation.

When Occupy Oakland can shut something like that down, the entire world has to pay attention. And that's what the protesters want, isn't it?

- By John Richardson at 4 Nov 2011 - 10:13am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

parallels between the Indian and American movements

Two Peas in a Pod

By THOMAS L. FRIEDMANGoa, India

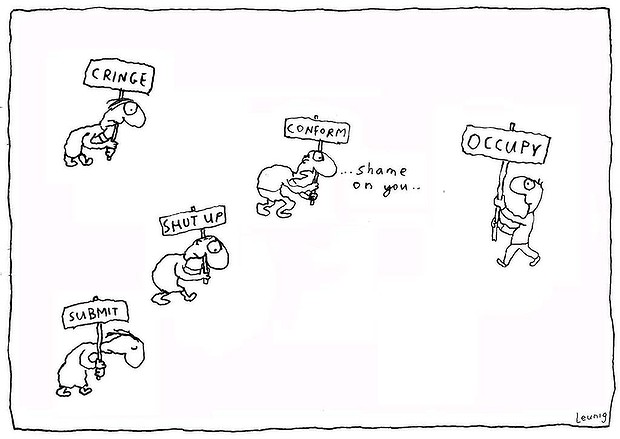

The world’s two biggest democracies, India and the United States, are going through remarkably similar bouts of introspection. Both countries are witnessing grass-roots movements against corruption and excess. The difference is that Indians are protesting what is illegal — a system requiring bribes at every level of governance to get anything done. And Americans are protesting what is legal — a system of Supreme Court-sanctioned bribery in the form of campaign donations that have enabled the financial-services industry to effectively buy the U.S. Congress, and both political parties, and thereby resist curbs on risk-taking.

But the similarities do not stop there. What has brought millions of Indians into the streets to support the India Against Corruption movement and what seems to have triggered not only the Occupy Wall Street movement but also initiatives like Americanselect.org — a centrist group planning to use the Internet to nominate an independent presidential candidate — is a sense that both countries have democratically elected governments that are so beholden to special interests that they can no longer deliver reform. Therefore, they both need shock therapy from outside.

The big difference is that, in America, the Occupy Wall Street movement has no leader and no consensus demand. And while it enjoys a lot of passive support, its activist base is small. India Against Corruption has millions of followers and a charismatic leader, the social activist Anna Hazare, who went on a hunger strike until the Indian Parliament agreed to create an independent ombudsman with the staff and powers to investigate and prosecute corruption at every level of Indian governance and to do so in this next session of Parliament. A furious debate is now raging here over how to ensure that such an ombudsman doesn’t turn into an Indian “Big Brother,” but some new ombudsman position appears likely to be created.

Arvind Kejriwal, Hazare’s top deputy, told me, “Gandhi said that whenever you do any protests, your demands should be very clear, and it should be very clear who is the authority who can fulfill that demand, so your protests should be directed at that authority.” If your movement lacks leadership at first, that is not necessarily a problem, he added, “because often leaders evolve. But the demands have to be very clear.” A sense of injustice and widening income gaps brought Occupy Wall Street into the street, “but exactly what needs to be done, which law needs to be changed and who are they demanding that from?” asked Kejriwal. “These things have to be answered quickly.”

That said, there are still many parallels between the Indian and American movements. Both seem to have been spurred to action by a sense that corruption or financial excess had crossed some redlines. In the United States, despite the fact that elements of the financial-services industry nearly sank the economy in 2008, that same industry is still managing to blunt sensible reform efforts because it has so much money to sway Congress. It seems to have learned nothing. People are angry.