Search

Recent comments

- democrats?

43 min 10 sec ago - fertilizers....

1 hour 10 min ago - hit?....

1 hour 8 min ago - cooperation....

5 hours 8 min ago - leave....

22 hours 58 min ago - costly....

23 hours 50 min ago - stormtroopers....

1 day 1 hour ago - friend-ships.....

1 day 3 hours ago - the lobby....

1 day 4 hours ago - not worth...

1 day 5 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

of hearts and minds...

from Robert Fisk...

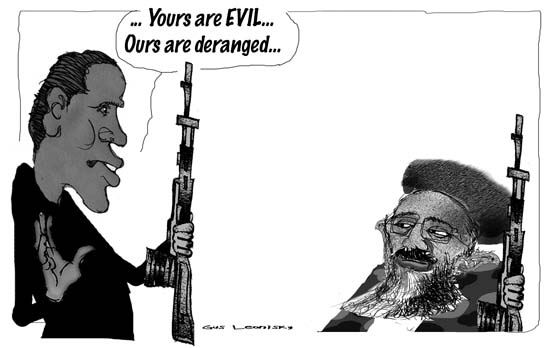

I'm getting a bit tired of the "deranged" soldier story. It was predictable, of course. The 38-year-old staff sergeant who massacred 16 Afghan civilians, including nine children, near Kandahar this week had no sooner returned to base than the defence experts and the think-tank boys and girls announced that he was "deranged". Not an evil, wicked, mindless terrorist – which he would be, of course, if he had been an Afghan, especially a Taliban – but merely a guy who went crazy.

- By Gus Leonisky at 21 Mar 2012 - 8:26am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

engaging in financial fraud...

TACOMA, Wash. — The attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, figure prominently in the still-evolving portrait of Robert Bales, the Army staff sergeant being held in a massacre of 16 villagers in southern Afghanistan. Like many others, Bales enlisted out of a sense of civic responsibility, his friends and attorney have said.

But Bales’s decision to join the Army also came at a pivotal point in his pre-military career — a career as a stock trader that appears to have ended months after he was accused of engaging in financial fraud while handling the retirement account of an elderly client in Ohio, according to financial records.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/staff-sgt-robert-bales-was-found-liable-in-financial-fraud/2012/03/19/gIQA4Ni2NS_story.html?hpid=z4

the Verfremdungseffekt...

“Unhappy is the land that breeds no hero.”

No, Andrea: “Unhappy is the land that needs a hero.”

The lines, Galileo responding to the parting words of his pupil, Andrea Sarti, who is furious and betrayed by his teacher’s recantation, are from the American version of Bertolt Brecht’s monumental biographical play about the great astronomer, currently onstage at the Classic Stage Company in New York, in a lean and sober production starring F. Murray Abraham. It’s a production very worth seeing, both as an introduction to a rarely-staged modern classic and as a demonstration of how even the most principled of artistic visions can turn back upon themselves, if pursued with honesty.

Brecht wrote the first draft of his play in 1938, at a moment when Nazi ascendancy justified a deep pessimism about progressivism and rationality’s ability to triumph in the world, when the world really did seem to need heroes for the cause of reason more than cold-eyed rationalists. He wrote the American version (in collaboration with Charles Laughton) shortly after the Americans dropped the first atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a moment that justified apprehension at a minimum about whether the progress of science as such was good for the progress of human flourishing. In different ways, each was a moment when the themes that Galileo represented—progress, science, reason—could be questioned. Would they triumph? Should they triumph?

A critical questioning of principles by examining the historical forces that underlie them is central to Brechtian theatre. But in this case, the principles being questioned are the very ones that Brechtian theatre aims to promote.

Brecht’s notion of the epic theatre was founded on the concept of the Verfremdungseffekt, usually translated as alienation or distancing effect. This was Brecht’s rebuke to Artistotle’s theory of drama, founded on the concept of catharsis, an emotional purging that takes place through identification with a character when he comes to a full understanding of the tragic inevitability of his fate. Brecht rejected this identification because he rejected tragic inevitability. His was to be a progressive theatre, a theatre that liberated the audience by alienating them from apparently familiar characters and situations, forcing them to confront the oppressive social structures that are, in his view, the real cause of what appears to be inevitable tragedy.

http://www.theamericanconservative.com/blog/anti-hero-of-science/