Search

Recent comments

- ask claude...

3 hours 1 min ago - dumb blonde....

10 hours 24 min ago - unhealthy USA....

10 hours 57 min ago - it's time....

11 hours 19 min ago - pissing dick....

11 hours 38 min ago - landings.....

11 hours 49 min ago - sicko....

1 day 38 min ago - brink...

1 day 54 min ago - gigafactory.....

1 day 2 hours ago - military heat....

1 day 3 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

staying the course .....

International summit split over cost-cutting exit strategy that would see security forces radically depleted as soon as West leaves

The blueprint for the West's exit strategy for the long war in Afghanistan is being set out in a critical meeting, with military officials and diplomats battling to prevent a proposed depletion of Afghan forces while the security situation remains precarious.

The conference in Brussels took place as an American newspaper published photographs yesterday of US soldiers next to the dismembered bodies of Taliban suicide bombers. The Defence Secretary, Leon Panetta, had to apologise to the Afghan delegation and fellow Nato ministers for the way the reputation of international forces had been "besmirched" by the actions apparently depicted in the pictures published in the Los Angeles Times.

The Independent has learnt that military commanders and diplomats have been arguing against an early cut of almost 40 per cent in the size of Afghan forces, just when they are supposed to be taking over security responsibility from Nato.

Under one proposal which was being considered, the numbers would shrink from 352,000 to 220,000 from 2014. The primary reason is cost: cutting manpower would lower the country's annual defence budget, which the international community will have to fund, from $6.2bn (£3.9bn) to $4.1bn.

However, senior diplomatic and military sources say they are increasingly confident that the cuts, which they say would have a hugely damaging effect at a particularly sensitive time, can be delayed.

The timetable, however, remained unclear after yesterday's meeting. The British Defence Secretary, Philip Hammond, said: "I think the intention is that the numbers will run through 2014, through 2015, and will then start to go down to get to the target number of 228,500, which will be achieved by the end of 2017. So the number will be achieved over a couple of years."

Mr Hammond added that the UK will provide $110m of the $1.3bn requested from Nato members towards the funding of Afghan forces. Washington will contribute the bulk of the remaining $2.7bn.

However, Nato's Secretary-General, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, pointed out that the decision on the timing of the depletion of Afghan security forces has not been decided and would depend on the security situation in the country. "Together with the rest of the international community we will play our part and pay our share in sustaining Afghan security forces at the right level for years to come," he said. But, he added, there was a consensus that the long-term strength "would be around 230,000".

Nato commanders concerned about the effect of too quick a cutback have received support in the US Congress. The dangers involved were raised with the US General John Allen, commander of the International Security Assistance Force, when he appeared before the Senate Armed Forces Committee in Washington. Senator Carl Levin, the chairman, asked: "Given that transition to a strong Afghan security force is the key to success of this mission, why [are we talking] about reducing the size of the Afghan army by a third?"

Yesterday in Brussels, Mr Panetta praised the actions of the Afghan forces during a fierce insurgent assault on Kabul last Sunday. "They moved quickly and effectively because of the training we had given them," he said.

A senior British officer said: "This is precisely why we must be careful about the message we send. Is it really wise to tell these guys risking their lives that they may lose their jobs a little down the line? Do we really want 120,000 disaffected men – trained to use arms – made unemployed, out on the streets, in an economy highly unlikely to find them other jobs?"

The Afghan Defence Minister, General Abdul Rahim Wardak, said: "Nobody can predict the security situation after 2014. Going lower on troop numbers has to be based on realities on the ground. Otherwise it will put at risk all that we have accomplished together with so much sacrifice."

However, the security situation will be considerably affected by the actions of Gen Wardak's government, diplomatic sources pointed out. Afghan national elections are currently scheduled for 2014 – after international forces have left.

The elections in 2010 were beset by violence despite the presence of tens of thousands of Nato troops, and President Karzai is considering bringing the next elections forward to next year. But that has led to accusations that he may also be attempting to manipulate the country's constitution in order to run for a third time.

"Even if he does not run, as he keeps on saying, any hint of the kind of corruption we had the last time would lead to great anger and also trouble," said an American diplomat. "Security is much improved, but we have to accept that pretty risky times lie ahead."

Nato Chiefs & Politicians At War Over Risky Afghan Withdrawal Plans

- By John Richardson at 19 Apr 2012 - 8:32pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

in the graveyard of empires .....

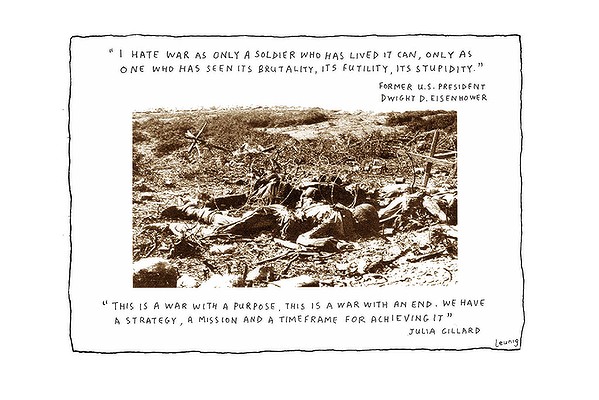

It was clear before Julia Gillard's address this week that it is past time for Australia's role in Afghanistan to end. Now the only question is whether our 1550 troops depart quickly or depart slowly. In either scenario, Kabul's fate will ultimately be determined by the Afghan people once the US-led coalition forces turn tail and run. The omens are not good.

Outside fortified enclaves, security is as bad as ever. Hamid Karzai's government, riven with internal conflict and endemic corruption, is rotten to the core. Poverty, illiteracy, drug lords and tribal vendettas will continue to sap legitimacy from any central government.

The Afghan army and police are unlikely to sustain a war against the insurgents. But the Taliban will still command considerable support primarily in the Pashtun heartland of southern and eastern Afghanistan.

Besides, the Taliban will still live there when coalition forces depart. Karzai knows it, which is why he is talking with the Taliban leadership. And the Afghan people know it, too. As a leaked US intelligence report, The State of the Taliban, recently revealed, they are coming to grips with the return of their former rulers.

Meanwhile, Washington's meddling in Central Asia has damaged relations with nuclear-armed Pakistan and reinforced strident anti-Americanism in what Barack Obama once privately called ''the most frightening country in the world''.

To be sure, many objectives of the 2001 mission have been accomplished. Osama bin Laden is dead. The al-Qaeda leadership is decimated. And the terrorist threat Afghanistan once posed has been eliminated.

That is why President Obama and the Prime Minister will try to spin the war as some sort of victory. The truth, though, is that our longest campaign will end badly.

If success is defined as creating a viable democratic state and ending a war with security enhanced, then Afghanistan is an expensive failure. For it is not within the power of the US and its allies to impose lasting peace and prosperity in such an implacably alien society. Only a political settlement can help achieve such an outcome. And only Afghans can deliver, and keep, such a deal.

All of this is a reminder that Afghanistan, taken together with Iraq, has not only cost the US and its allies dearly in blood and treasure. It has also demonstrated the limits of what Robert Menzies called ''our great and powerful friend''.

In the aftermath of September 11, the conventional wisdom among political leaders on both sides of the Pacific was that the US should lead a coalition of willing states to not only end terrorism in but export democracy to the Middle East. Or in the words of one Bush adviser: ''We are an empire now, and when we act we create our own reality.''

That this view was widely held in the trauma following September 11 was understandable. That the rapid downfall of the Taliban tyranny in December 2001 and Saddam Hussein's regime in April 2003 gave it superficial credibility was unfortunate. That the Afghan and Iraq debacles have imposed tests that expose its falsity is good.

For both wars have shown that when it comes to defeating tribal warlords in mediaeval societies, even a global hegemon like the US can find itself wrong-footed and outwitted, not so much an eagle as an elephant.

I have been one of those who have argued for some time that even if the US-led coalition stayed for another decade, as the Prime Minister once suggested, we would still fail to remake Afghanistan into a Western-style democracy. But mine is hardly an isolated view among conservatives.

Many British Tories and US Republicans - and not just Ron Paul's followers - recognise that the days of a Pax Americana are over and that Washington will be more discriminating and selective in its foreign policy commitments.

The great British historian A. J. P. Taylor once said the road to hell is paved with good intentions. And there is no question the 2001 decision to invade Afghanistan and topple the turbaned tyrants who were in cahoots with the September 11 perpetrators was morally right and strategically sound.

But it's neither in our competence nor our interest to conduct a foreign policy based on the illusion democracy is an export commodity in the Muslim world. Too bad it's taken a quagmire in what is known as the "graveyard of empires" to shatter that ideal.

It Was Inevitable That Afghanistan Was Going To End Badly