Search

Recent comments

- MAGA fools

1 hour 15 min ago - the ugliest excuse to go to war.....

11 hours 25 min ago - morons....

13 hours 17 min ago - idiots...

13 hours 19 min ago - no reason....

14 hours 24 min ago - ask claude...

17 hours 44 min ago - dumb blonde....

1 day 1 hour ago - unhealthy USA....

1 day 1 hour ago - it's time....

1 day 2 hours ago - pissing dick....

1 day 2 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the long goodbye .....

Almost every political observer recognises that unless something altogether unexpected happens, by late 2013 Australia will have an Abbott government. The more contentious question is what has gone wrong for Labor. This piece is offered as a contribution to a necessary debate.

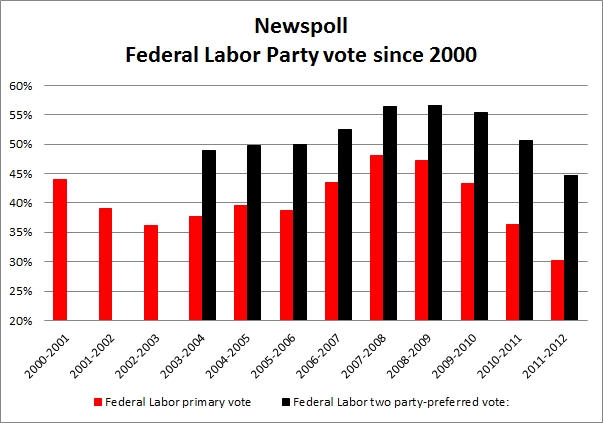

The following chart, which is based upon the fortnightly Newspoll, is used to demonstrate the presently parlous state of the federal Labor government. I have calculated both the average annual first preferences and, where they were estimated by Newspoll, the average annual two-party-preferred vote of the federal Labor Party since 2000. The year in this survey begins on April 1 and ends on March 31.

There is one obvious conclusion to be drawn from this chart, which covers, roughly, the final seven and a half years of Howard and the four and a half years of Rudd and Gillard. In the recent history of the Labor Party – during the period of the leadership of Beazley, Latham, Beazley, Rudd and Gillard – from the viewpoint of public support, the past twelve months have been both woeful and anomalous. Between April 1 2000 and March 31 2011, a period covering many political swings and roundabouts, the average federal Labor primary vote was 41.2% and the average two-party-preferred vote 50.6%. Between April 1 2011 and the end of March 2012, the average annual primary federal Labor vote was 30.2% or 11% lower than the 2000 to 2011 average, and the average annual two party-preferred vote 44.7% or 5.9% lower than the 2000 to 2011 average. During the past year the primary vote of the Gillard government has averaged 6% less than the worst annual average of the years between 2000 and 2011 and 17.8% less than the best annual average of these years.

Nor has the collapse of the federal Labor vote been gradual. An interesting comparison is the one between the Rudd and Gillard governments. Under Rudd (November 2007-June 2010), Labor’s average annual primary vote was 43.2% and its two party-preferred vote 55.8%.

Under Gillard (since June 2010) it has been 32.8 % and 46%, a collapse in both cases of about 10%. It is frequently said and still commonly believed that Rudd lost the Prime Ministership because of poor polling in the three months before his unseating. This is obviously false. In the last six fortnightly Newspolls prior to the internal party coup, the Rudd government won 56%, 54%, 49%, 50%, 51% and 52% of the two party-preferred vote.

Since July 2011, when the collapse of the Labor vote moved into hitherto uncharted territory for post-war federal Labor, the Gillard government’s average, two party-preferred vote was 44%. Sometimes the recent performance of the Gillard government is compared to the performance of the Howard government in the first months of 2001, when most commentators (including yours truly) thought its defeat inevitable. This however is also false. Between February and June 2001, the average of the Coalition’s primary vote was 38.2% almost 10% higher than the Gillard government’s average of 29.4% since July 2011.

The closest precedents for the past nine months of the Gillard government are the performances of New South Wales Labor government between March 2010 and 2011, where Labor received on average some 25% of the primary vote (compared with Gillard’s post-July 29.4%) and 39% of the two party-preferred vote (compared with Gillard’s post-July 44%) or the Bligh government from March 2009 to last weekend’s election where the average primary vote, as measured by Newspoll, was 30.3% (compared with Gillard’s post-July 29.4%) and its two party-preferred vote 43% (compared with Gillard’s post-July 44%).

Even though New South Wales Labor’s primary vote was lower in the March 2011 election than Queensland Labor’s primary vote in the election last weekend, because of the peculiarity of electoral geography, New South Wales Labor won a higher proportion of seats.

The federal electoral geography is closer to New South Wales than Queensland. Although it seems almost certain that the outcome will be less disastrous in terms of seats and votes—with Victoria and maybe Tasmania slightly moderating the trend—ominously, on present indications, the New South Wales election of March 2011 seems the one that most closely prefigures what might happen to the federal Labor government in 2013.

How is the unpopularity of the Gillard government to be explained?

It is very common to explain the malaise of contemporary Labor by concentrating on deep structural factors. These factors can be summarised, brutally, like this. The influence of the trade unions within the party is too great. The influence of the non-union parts of the party, that is to say the rank and file membership inside the fast-withering party branches, is too weak. The formalised factions and their leaders wield altogether too great an influence over the inner workings of the party. The party has lost the capacity to recruit outstanding candidates from varied backgrounds to its parliamentary wing, now drawing its new parliamentarians primarily from loyal time- servers who have previously worked in the trade unions or as political advisers. The party has lost the ability to attract the allegiance of idealistic younger people almost all of whom, if they move into party political engagement, gravitate to the Greens. The Labor Party has gradually lost a large part of its historical demographic – the traditional working class – and more recently also of its newer social base, the left-leaning professionals, who have also gravitated to the Greens. Finally, having embraced neo-liberalism under Hawke and Keating, and having absorbed populist conservatism from the prevailing atmosphere of the Howard years, the party is ideologically disoriented. It now appears to both the electorate at large and to former party members and voters, to stand for nothing, to have no transformative agenda, to be defined by no real beliefs.

There is no doubt considerable truth in all these claims about the structural weaknesses of the contemporary Labor Party. However as an explanation of the federal Labor government’s present discontents concentration on such matters does not seem to me at all persuasive. All these structural factors are long or middle term. Yet the collapse in the popularity of federal Labor has happened very suddenly. Under Rudd, trade unions were as powerful as they are now; party branches were as weak; parliamentary candidates were selected from no less narrow a base; left-leaning students and professionals were almost as attracted to the Greens; the Labor program and ideology were hardly less confused than at present. And yet for two and a half years Kevin Rudd led one of the most popular governments in post-war Australian history. As long or middle term factors cannot explain the unpopularity of the Gillard government during the past several months, another kind of explanation seems required. The one I favour is historical.

In my view, the strange and rather sudden collapse of the Gillard Labor government is grounded in a series of mistakes and miscalculations, beginning with Rudd in 2008, spiralling out of control in 2010, but only becoming irreversible and lethal with Gillard around the middle of 2011.

The first strategic error was Rudd’s 2008 asylum seeker policy. Rudd might have retained the shell of the Pacific Solution – the threat of offshore processing for asylum seekers who arrived by boat – and humanised the policy by abandoning mandatory detention (beyond a few weeks for health and security checks) and increasing the number of refugee and humanitarian placements from 13,500 to 20,000. As the cruel Howard policy had indeed “stopped the boats”, such a policy would have inflicted no suffering and would have given the prospect of a decent life to additional thousands of refugees. Rudd’s policy inevitably and predictably saw a return of the boats. A different policy would have benefited more refugees but would not have been open to political exploitation by a ruthless populist conservative like Tony Abbott.

The second strategic error concerned a failure of administrative attention to detail during the highly successful Rudd government stimulus program. The schools building program was vulnerable to criticism over cost blowouts in the public sectors in New South Wales and Victoria but was, on balance, popular. The home insulation program, however, did the government considerable harm because of its thoughtlessness and because its slovenly implementation cost several lives.

By 2010, then, because of the trouble facing its asylum seeker policy and its insulation stimulus program, the still highly popular Rudd government became for the first time somewhat vulnerable.

The third strategic error of the Rudd government was to trust the Coalition and to cold-shoulder the Greens regarding negotiations leading towards its most important piece of legislation – the emissions trading scheme. Rudd placed faith in the capacity of Malcolm Turnbull to deliver bipartisan support. When Turnbull lost the Liberal Party leadership in November 2009, and when Tony Abbott made it clear that the Coalition would oppose the climate change legislation, the Rudd government began to lose its way. Rudd could have now opted for a double dissolution and negotiations with the Greens. Instead he allowed members of his cabinet – including his deputy, Julia Gillard – to talk him into postponing the emissions trading scheme for the next three years. Not only did it now seem as if Rudd believed in nothing. In considerable numbers left-leaning inner city voters now defected, probably permanently, to the Greens.

The fourth strategic error followed close upon the climate change debacle. Badly stung, Rudd now attempted to prove that he did indeed believe in something, by announcing his government’s commitment to the Ken Henry committee’s suggestion of a resource rent mining tax. The error here was not with the decision but with the absence of political nous at the moment of announcement. Rudd needed to prepare the ground more carefully. He might have commissioned, for example, a white paper on the new mining tax, and initiated a long-term and broad-ranging national conversation on how not to squander the resources boom. In the way the mining tax was announced, Rudd underestimated the ruthlessness and the deep pockets of the mining interest. He underestimated the ideological enmity of the Murdoch press, especially the Australian. And he overestimated the loyalty of his party.

The fifth strategic error of the contemporary federal Labor Party was probably the most important. By June 2010, although its reputation had been badly dented inside what might be called the political nation, the Rudd government still had not lost the trust of the electorate. There is a lot of ruin in governments; they can withstand many errors and bad patches. By June 2010, there was for Rudd still time for repair. Mystery still surrounds the decision now taken within the party – to remove one of the more popular Prime Ministers in recent Australian history, the man who led one of the only nations in the Western world to emerge from the global financial crisis without recession. There were three main consequences of the swift and secretive unseating of Kevin Rudd. The coup made it impossible for the Labor government to run on its record at the next election. The rushed mining tax compromise the coup leaders swiftly negotiated with the big three miners ensured that the resources boom was indeed certain to be squandered. Most importantly, the rather sinister quality surrounding the coup instantly revived the old Menzies canard, that the Labor was a party run by “faceless men”.

The sixth strategic error is the one I find most difficult to explain. Having convinced Rudd to postpone the emissions trading scheme legislation for three years, having promised the electorate that her government had no intention of introducing a price on carbon, having scrambled back to government as the leader of a minority government – Prime Minister Gillard now signed an agreement with Greens for the creation of a parliamentary committee to broker the outlines of a carbon tax/emissions trading scheme. Given the problems this created, Gillard’s thinking is almost impossible to fathom. On the one hand, if Gillard did believe in the need for a carbon price, why had she convinced Rudd to postpone for three years? On the other hand, if she did not believe in the necessity of a carbon price, why did she agree to a negotiating process with the Greens? Gillard could not argue political necessity. There was no possibility that, in the absence of an agreement, the one Greens member of the House of Representatives, Adam Bandt, would have supported an Abbott government. By talking Rudd into postponing his climate change legislation, Gillard helped destroy Rudd’s reputation. By promising the Australian people before the election that her government would not introduce a price on carbon, and then signing an agreement shortly after the election for a process leading to carbon price legislation, she helped destroy her own. Gillard outlined her carbon tax legislation in July 2011. It is no accident that it was in July 2011 that her government’s already poor public opinion polls now went into free-fall. Gillard was not only introducing a new tax whose absolutely real necessity she was incapable of explaining. She was also a “liar”.

Labor’s seventh strategic blunder came earlier this year. It was always inevitable that Kevin Rudd at some stage would make an attempt to regain the leadership of the Labor Party. Not only did he regard his removal as illegitimate. All opinion polls revealed that he was almost twice as popular as his successor, Julia Gillard. If Rudd had been patient and had waited for the Queensland election and for the almost inevitable succession of disastrous public opinion polls that would follow, by mid-year support for his return within the Labor Party caucus might have gradually become almost irresistible. In the looming leadership contest, however, inside the Rudd camp, one misstep followed hard upon another. Rudd and his supporters signalled his leadership ambitions far too openly. When his enemies in the Gillard camp decided to publicly acknowledge that Rudd was preparing a challenge, rather than waiting to be dismissed as Minister for Foreign Affairs and acquiring thereby a second halo of popular martyrdom, Rudd hastily resigned. Flushed out by the Gillard loyalists, Rudd’s challenge had come far too early. Prime Minister Gillard was as a consequence overwhelmingly endorsed. The one, no doubt slim possibility, of a Labor election victory under a second Rudd Prime Ministership, had been forfeited.

There are grave structural weaknesses within the contemporary federal Labor Party. There are also deep factors threatening the future of all parties within the social-democratic tradition. All these structural weaknesses and historical challenges for social democracy eventually need to be assessed and where possible corrected. But in my opinion they are not responsible for the federal Labor government’s present discontents (or indeed for the disasters besetting the state Labor parties). Federal Labor’s woes rest rather on a string of particular, mostly avoidable, tightly interconnected, strategic blunders. As a consequence of these blunders, Tony Abbott now seems certain to be Prime Minister before the end of 2013.

- By John Richardson at 25 Apr 2012 - 8:40am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the kiss of death .....

Westpac's chief executive, Gail Kelly, has urged her fellow business leaders to be prepared to work with Julia Gillard and to put aside the combative approach to policy debate which has been dogging the minority Labor government.

The powerful banking boss also gave an endorsement of the Prime Minister's attempt to reach out to business, even in the face of intense and sometimes bitter criticism over issues ranging from the carbon tax and the rush to deliver a surplus.

''It's important that big business rolls up its sleeves and engages constructively and I think the Prime Minister is also adopting this approach. She is a consultative person,'' Mrs Kelly told the Herald. The comments mark a critical turn of support for Ms Gillard, who is lagging in the polls.

Mrs Kelly herself has often come under attack from Canberra on issues from mortgage pricing to job cuts at her bank. And in an apparent slight to big miners that campaigned against the mineral resource rent tax, Mrs Kelly also hit out at businesses attempting to ''run an agenda through third parties or the media''. This approach was not conducive to economic reform, she said.

Westpac and its rivals have come under intense criticism from members of the government in recent years for failing to pass on the Reserve Bank cuts to official interest rates in full. Anger was sparked again after Westpac's flagship retail bank last week passed on just 37 basis points of the Reserve Bank's 50 basis point cut.

''She [Ms Gillard] stepped into the role. She does listen, I can tell you from personal experience,'' Mrs Kelly said. ''Even if you have a different starting point she will listen. And I really respect that in politicians.''

Mrs Kelly said she has had a number of ''robust discussions'' with Ms Gillard on policy issues where the two may not agree. ''But we work our way through them and there's a very healthy respect.''

While she declined to discuss the nature of the talks, the banks and the government have been at loggerheads over whether the sector has been making excessive profits by pushing through out-of-cycle interest rate cuts.

Under pressure to fund lending from deposits, the banks argue the higher cost of raising funds is forcing them to hold back some of the reduction in interest rates.

Hands-Off Julia Gillard Says Westpac Boss