Search

Recent comments

- stenography.....

3 hours 25 min ago - black....

3 hours 23 min ago - concessions.....

4 hours 25 min ago - starmerring....

8 hours 30 min ago - unreal estates....

12 hours 16 min ago - nuke tests....

12 hours 20 min ago - negotiations....

12 hours 23 min ago - struth....

1 day 2 hours ago - earth....

1 day 2 hours ago - sordid....

1 day 3 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

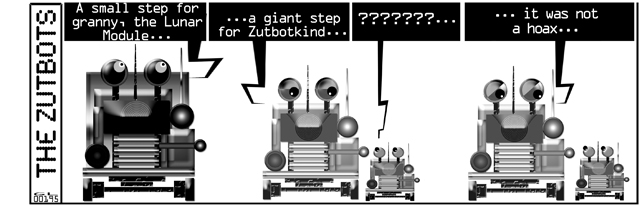

the zutbots...

- By Gus Leonisky at 27 Aug 2012 - 7:56am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

steps on the moon, for humankind...

Neil Armstrong, first man to step on the moon, dies at 82

By Paul Duggan, Published: August 26Neil Armstrong, the astronaut who marked an epochal achievement in exploration with “one small step” from the Apollo 11 lunar module on July 20, 1969, becoming the first person to walk on the moon, died Aug. 25 in the Cincinnati area. He was 82.

His family announced the death in a statement and attributed it to “complications resulting from cardiovascular procedures.”

A taciturn engineer and test pilot who was never at ease with his fame, Mr. Armstrong was among the most heroized Americans of the 1960s Cold War space race. “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” he is famous for saying as he stepped on the moon, an indelible quotation beamed to a worldwide audience in the hundreds of millions.

Twelve years after the Soviet satellite Sputnik reached space first, deeply alarming U.S. officials, and after President John F. Kennedy in 1961 declared it a national priority to land an American on the moon “before this decade is out,” Mr. Armstrong, a former Navy fighter pilot, commanded the NASA crew that finished the job.

His trip to the moon — particularly the hair-raising final descent from lunar orbit to the treacherous surface — was history’s boldest feat of aviation. Yet what the experience meant to him, what he thought of it all on an emotional level, he mostly kept to himself.

Like his boyhood idol, transatlantic aviator Charles A. Lindbergh, Mr. Armstrong learned how uncomfortable the intrusion of global acclaim can be. And just as Lindbergh had done,he eventually shied away from the public and avoided the popular media.

In time, he became almost mythical.

Mr. Armstrong was “exceedingly circumspect” from a young age, and the glare of international attention “just deepened a personality trait that he already had in spades,” said his authorized biographer, James R. Hansen, a former NASA historian.

In an interview, Hansen, author of “First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong,” cited another “special sensitivity” that made the first man on the moon a stranger on Earth.

“I think Neil knew that this glorious thing he helped achieve for the country back in the summer of 1969 — glorious for the entire planet, really — would inexorably be diminished by the blatant commercialism of the modern world,” Hansen said.

“And I think it’s a nobility of his character that he just would not take part in that.”

http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/neil-armstrong-first-man-to-step-on-the-moon-dies-at-82/2012/08/25/7091c8bc-412d-11e0-a16f-4c3fe0fd37f0_print.html

Not only the blatant commercialism would diminish the feat, including and mostly the engineering feat in which a lot of calculation were done on computers that had small pea brains, but the project and its result attracted scorn from too many people who thought the whole thing was a hoax...

I have the feeling that anyone who has set foot on the moon would be in awe of the relative universe in which we live in... The enormous dome of black in which the stars do not twinkle, the planet earth seen from 370,000 kilometres away, the blazing sun, the weird gravity, the finicky technology that put you there, all would make an amazing impression that transcended our petty disputes and desires... And there are still some people who think god makes sense... But many such beliefs would be rattled in the face of the real space-time-energy conundrum...

they glow red hot in the dark...

It's a neat trick, and one that NASA has used before. Since the 1960s, the US has been launching nuclear-powered spacecraft. The first were military satellites. That worked swell, except that when the mission ended, you had a radioactive pile of junk orbiting the planet. And every now and then, one would fail to launch or fall back to Earth. That was bad for PR.

These days, NASA puts nuclear fuel on things that aren't coming back. The Voyager missions that left the solar system carried it, as did the first Martian missions, the Viking landers. It's particularly useful when you're going far from the sun - places where solar panels don't work.

The particular kind of fuel inside Curiosity is called plutonium-238. It's the perfect stuff for the job: it's extremely radioactive, so it gives off plenty of heat, but the type of radioactive particles released by plutonium-238 can't even penetrate a sheet of paper. As long as you don't touch it or swallow it, plutonium-238 is safe, and with a half-life of 87.7 years, it decays slowly enough that a fairly small supply can power a spacecraft for a decade or more.

But plutonium-238 isn't easy to come by. It doesn't exist in nature, and only two places in the world have made serious quantities of it. Both made something else: nuclear warheads. You see, plutonium-238 is really a byproduct of the process for making another kind of plutonium, known as isotope 239. Plutonium-239 is the real terror: almost all modern warheads in the US arsenal use it as a trigger. When it explodes, it sets off an even larger thermonuclear device capable of flattening a midsized city (say, 100,000 to 200,000 people). Russian warheads have even higher yields.

In the 1960s, the US and Soviet Union were hungry for 239. They built secret reactors that irradiated uranium to create it. Then they dissolved the uranium-plutonium mix in acid and used a slew of toxic chemicals and solvents to isolate the plutonium. The work provided the plutonium-239 for thousands of tiny, high-efficiency warheads - many of which still sit atop missiles today.

Plutonium-238, the stuff in the rover, was an afterthought. NASA asked the Atomic Energy Commission to get some for the agency's satellites in the 1950s, after falling behind in the space race. The eggheads at the nuke plant came up with a clever way of producing it from unwanted isotopes they were just going to throw away anyway. The Soviets had the same idea. Using a similar system of acids and solvents to dissolve their uranium fuel, the Soviets skimmed plutonium-238 off their production operation at a secret bomb factory in the Ural Mountains. It went on for decades: In came uranium fuel, out went plutonium-239 for the bombs, plutonium-238 for the spacecraft, and many other isotopes for other needs.

Read more: http://www.smh.com.au/technology/technology-news/curiositys-dirty-little-secret-20120828-24xvn.html#ixzz24taNKPqD