Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

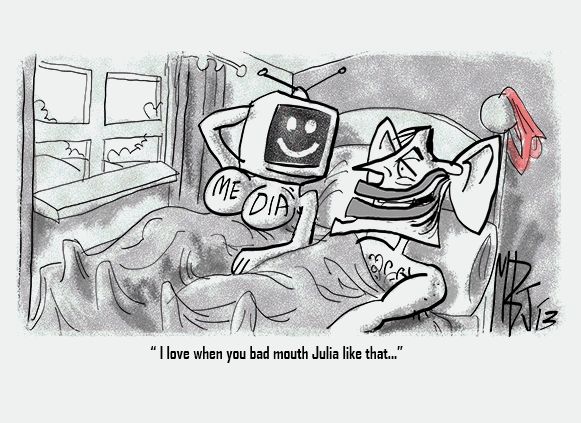

mind games ....

There are some words and phrases that almost inevitably crop up in politician-speak across the ideological spectrum. No matter how fond one might be of one’s own relatives, for instance, by the conclusion of an election campaign we’re all heartily sick of families, be they ‘modern’, ‘working’, or otherwise. Some words, though, are a little more abstract, such as community and the mainstream.

Consider also divisiveness.

In his clear rebuttal of the views of the Dutch anti-Muslim politician Geert Wilders, Tony Abbott stated:

“I think that the Muslims in this country see themselves rightly as fair dinkum, dinky-di Australians, just as the Catholics and the Jews and the Protestants and the atheists…We don’t like to divide ourselves on the basis of race, of faith, of colour, of class, of gender. That’s one of the great strengths of our country. We are always conscious of what we have in common, rather than the things that divide us.”

Beyond this specific issue, opposition to divisiveness is a recurring theme for the Opposition Leader.

Responding to Treasurer Wayne Swan’s recent accusation that the Federal Coalition had adopted a “callous Tea Party-inspired ideology”, Abbott countered:

“You will never find from me, or from any government I lead, the kind of politics of division which I fear others seek to introduce”.

Abbott has also stated previously:

“My message for the Australian people is that I am never going to try to divide them…on the basis of class, on the basis of gender, on the basis of faith.”

Divisive politics are harmful; wedge tactics that play voters off against each other have a corrosive effect on our democracy.

We need to look more closely, though, at the way the concept of division is used in our political vernacular.

In particular, the depiction of one’s opponents as ‘divisive’ is a familiar conservative tactic. We give you unity and togetherness, goes the argument; the other lot keep trying to carve up the nation with reference to irrelevant issues like class (and, in more recent decades, gender, ethnicity and sexuality). Recall John Howard’s statement that

“…the things which unite us as Australians are infinitely greater and more enduring than the things that divide us.”

It’s a nice thought; one of those comforting stories we tell ourselves during times of trial or international sporting events. There is value in working towards collective goals and the nation state remains a key political actor.

The problem with these sentiments is that where there are divisions and it is proposed to address them, these efforts can be portrayed as threats to national unity.

Consider the proposed referendum to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution and remove racially discriminatory provisions. What is particularly noticeable in the debates around this issue is the argument that such a move would be divisive. Such responses seem to presuppose that we currently enjoy racial harmony and substantive equality as between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, and that therefore addressing the legacy of colonialism would somehow create division rather than recognising some fairly obvious facts. As noted elsewhere, conservatives sometimes find it difficult to acknowledge the ongoing existence of racism — instead, it is easier to accuse those who raise this issue of stimulating conflict.

Similarly, Abbott’s stated aim not to divide Australians on the basis of class, gender and faith is admirable. We shouldn’t resile from stating the obvious, though — that there are already divisions there and not talking about them won’t make them disappear.

For instance, income inequality appears to be rising, ‘reflecting differences both between regions, and within major cities’; a recent report by the Workplace Gender Equality Agency (which has been subject to critique) found that the annual gender salary gap had risen from $2,000 a year in 2011 to $5,000 in 2012; and the accommodation of different religious groups within a secular state will necessarily involve disagreement from time to time — consider the concerns expressed on last week’s Q&A about the teaching of creationism in our public schools.

These distinctions are not a linguistic trick created by conflict-fostering conspirators — they are rooted in empirical fact.

Claiming that a policy or a public conversation on an issue is ‘divisive’ is an excellent, if manipulative, tactic. Firstly, it makes your opposition look like nasty people who want to create conflict just for the hell of it. ‘Divisive’ comes from the same songbook as ‘envy politics’ — it is a useful way of associating one’s ideological opponents with negative emotions.

Secondly, historically an emphasis on national unity has helped to distract from the very fact that there are some people, industries or interest groups with more of the pie than others.

Seeking to rectify inequality is often lumped in together with divisiveness for its own sake, and it is, indeed, a marvel that attempts to ensure that disadvantaged schools are adequately funded are inevitably derided as ‘class warfare’ while, for instance, the mining industry’s 2010 campaign against the resources super-profits tax was not widely regarded as such.

Australians are, like every other nation, characterised by our differences as well as our similarities. If we can’t talk about the cracks in our egalitarian gloss for fear of being ‘divisive’, the appearance of unity will come at too high a price.

- By John Richardson at 26 Feb 2013 - 11:13am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

1 hour 40 min ago

2 hours 15 min ago

2 hours 31 min ago

2 hours 47 min ago

7 hours 28 min ago

7 hours 38 min ago

8 hours 4 min ago

20 hours 35 min ago

1 day 1 hour ago

1 day 6 hours ago