Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

turn, turn, turn .....

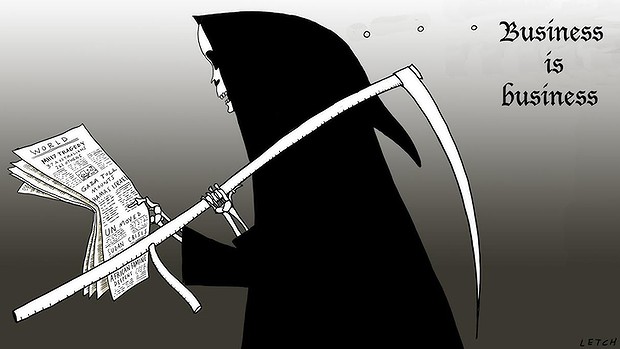

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the value of human life. About the lives so cheaply lost on MH17. About the anger and grief this tragedy has unleashed. About the sense of sacredness and solemn ceremony that followed it. There’s something cathartic about all this. That we mark this with ritual public grieving tells us that these lives – and therefore our own lives – are sanctified; that their termination is an almost blasphemous violation. On some level this reassures us, which is probably why we pore over news coverage of such events, seizing on small harrowing details and the personal stories of the victims.

But I’ve also been thinking a lot about why it is these lives particularly that have earned such a response. The more I heard journalists and politicians talk about how 37 Australians were no longer with us, the stranger it began to sound. Something of that magnitude happens just about every week on our roads, for instance. In the last week for which we have official data, 29 people were killed this way. The youngest was two. We held no ceremonies, and we had no public mourning of the fact that they, too, were no longer with us.

Why? I don’t ask critically, because I’m as unmoved by the road toll as anyone. But it’s surely worth understanding how it is we decide which deaths matter, and which don't; which ones are galling and tragic, and which ones are mere statistics. We tell ourselves we care about the loss of innocent life as though it’s a cardinal, unwavering principle, but the truth is we rationalise the overwhelming majority of it. What does that tell us about ourselves?

Here, the most obvious counterpoint is the nightmare unfolding in Gaza. As I write this, nearly 600 people – overwhelmingly civilians a third of whom are children – have been killed. By the time this goes to print, that number will be redundant. There’s grief, there’s anger and there’s some international hand-wringing, but nothing that compares with the urgency and rage surrounding MH17, even if there is twice the human cost.Advertisement

If you take your cues from social media, on which this comparison is being relentlessly drawn, the reason is simple: Palestinians are not rich Westerners, and so their lives simply don’t matter. No doubt there’s some truth to this: humans are tribal animals, and we’re as tribal in death as we are in life. But it’s not an entirely satisfactory explanation because it comes from people who would likely exempt themselves from this rule. And yet those same people have almost certainly grieved comparatively little over the thousands of South Sudanese killed in the past six months, or the 1.5 million to have been displaced. Should we conclude they value African lives less than Palestinian ones?

It’s not merely a matter of cultural affinity. Consider the Egyptian press, which has wholeheartedly embraced the Israeli offensive. “Sorry Gazans, I cannot support you until you rid yourselves of Hamas,” wrote Adel Nehaman in Al-Watan. He was comprehensively outdone by Al-Ahram’s Azza Sami who tweeted “Thank you Netanyahu, and God give us more men like you to destroy Hamas”. Then she prayed for the deaths of all “Hamas members, and everyone who loves Hamas”. Meanwhile, television presenter Tawfik Okasha urged Egyptians to “forget Gaza”, adding for colour that “Gazans are not men” because they don’t “revolt against Hamas”. That, presumably includes the hospital patients or the kids playing football on the beach who have been bombed in the past week or so.

This is about as thorough a dehumanisation of Gazans as you’ll find anywhere in the world. Israel’s media doesn’t even come close. And this in a country where the Palestinian cause has been a kind of social glue for decades. But that’s what happens when the sanctity of life meets the power of politics. For the Egyptian media – now effectively a propaganda arm of the government – Gaza merely represents a chance to attack the Muslim Brotherhood, from which Hamas emerged. It doesn’t matter who dies. It doesn’t matter how many. What matters is that their lives – and especially their deaths – can be used in the service of the story they are so desperate to tell.

And that, I fear, is a universal principle. It is not merely the death of innocents that moves us, even in very large numbers. It is the circumstances of it that matter. We decide which deaths to mourn, which to ignore, which to celebrate, and which to rationalise on the basis of what story we want them to tell. Palestinian deaths matter more than Sudanese ones if you want to tell a story of Israeli aggression. Israeli deaths matter more than Palestinian ones if you want to tell a story of Hamas terrorism. Asylum seeker deaths at sea matter more than those on land if you want tell a story about people smuggling. But a death in detention trumps all if your story is about government brutality. And a death from starvation matters if you want to tell a story about global inequality – which so few people do. Everyone will insist they’re merely giving innocent human lives their due. And that’s true but only in the most partial sense. These are political stories driven by political commitments.

MH17 allowed us to mourn and to rage because it delivered a story we were well prepared to tell. It’s easy to rage when the plot is one of Russian complicity, roguishness and cover-up. And frankly, Russia deserves the whack it’s getting for its handling of the aftermath. But in my most naive moments I hope for a world where the value of human life is universal enough that we can outrage ourselves; where we can tell the stories we don’t particularly want to; the stories in which we are neither the heroes nor the victims, but the guilty. That’s what we’re asking of Russia. One day someone mourning no less than we are will ask it of us.

MH17, Gaza and the value of human life

- By John Richardson at 25 Jul 2014 - 2:25pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

2 hours 35 min ago

4 hours 27 min ago

4 hours 48 min ago

7 hours 18 min ago

8 hours 23 min ago

8 hours 34 min ago

10 hours 34 min ago

11 hours 35 min ago

12 hours 3 min ago

1 day 1 hour ago