Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

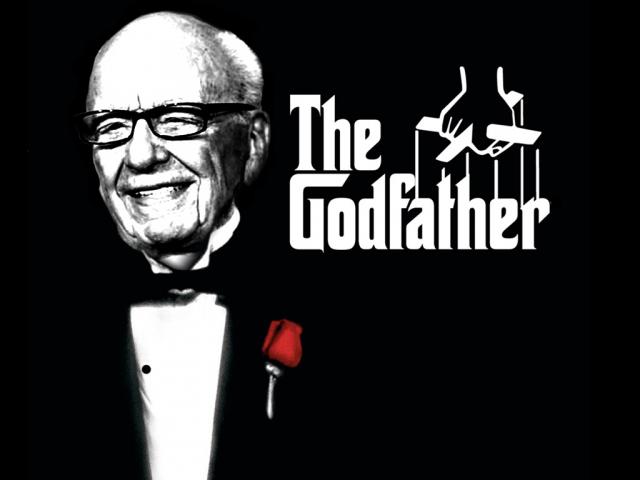

the hand that feeds ....

Paul Kelly’s The End of Certainty, published in 1992, is probably the most influential book of contemporary Australian political history written in the past 50 years. In it, Kelly married a detailed chronology of the surface politics of the Hawke–Keating era with a compelling historical interpretation – the rise of economic liberalism and the unravelling of what he called the Australian Settlement, the old protectionist-interventionist-regulated state.

In 2009, Kelly published a sequel, The March of Patriots, a study of the decade between the ascension of Paul Keating in 1991 and John Howard’s third election triumph in 2001. Kelly argued that, despite the apparent differences over the kind of country they imagined, Keating and Howard created in Australia a new social model of universal significance, halfway between the European welfare state and the American free market. Although the quality of the chronology was no less accomplished than in The End of Certainty, the book’s rather implausible interpretation left no discernible mark on the national imagination. Not even, it seems, on Kelly’s.

In August, he published the third of the trilogy, Triumph and Demise, a study of the turbulent six Rudd and Gillard years. By now the splendid new Keating–Howard social model he had christened Australian Exceptionalism has been overtaken by the arrival of an unwelcome state of affairs that, with his instinct for hyperbole, Kelly calls the Australian Crisis. While the strengths of Triumph and Demise’s predecessors are still present – narrative drive, familiarity with detail, the insider’s privileged access to the main players – something has gone seriously wrong.

Kelly’s argument represents the endlessly repeated house view of his employer, News Corp, and its flagship newspaper, the Australian. It goes like this. Foremost in the explanation of Labor’s abject failure is the problem of Kevin Rudd. Rudd’s dysfunctional personality alienated colleagues in cabinet, the caucus and the public service. His quest for climate-change action was both unnecessary and politically bungled, especially after Tony Abbott, a climate-change denier, became Liberal Party leader. Rudd’s fight with the mining interests in 2010 was altogether mishandled and imprudent. Because Rudd was unreliable on the question of the free market – as seen both in the reckless, big-spending Keynesian stimulus package during the global financial crisis and in his heretical critique of neo-liberalism – he created a new public culture of deficit spending and unfulfillable Whitlamite expectations. Despite this, however, Rudd’s removal as prime minister by the Labor caucus and faction leaders in June 2010 proved a disaster. The coup was never adequately explained to the people. Because of his strange personality, until his return to the prime ministership Rudd became a permanent destabiliser of Labor.

Although Rudd’s successor, Julia Gillard, had a successful relationship with her Labor colleagues, Kelly has it that her special problem was a political “tin ear”. With her exaggerated claims about misogyny, for example, she progressively alienated “stony and silent” male voters. More deeply, Gillard turned her back on the market values that had driven the Hawke – Keating reforms. Not knowing how to get on with big business or influence Sydney’s “power structure”, she returned to the hopelessly outmoded trade union–based Labor values of the past. Even worse, Gillard formed an inexplicable and suicidal alliance with the loathsome Greens, which deepened the post-Whitlam existential crisis for Labor: its inability to reconcile the interests of its traditional blue-collar base with the social justice and environmental fantasies of its university-educated progressive supporters. These failures of Labor under Gillard came, according to Kelly, at the time of a decline in the terms of trade and the beginning of the end of the mining boom. In combination with the rise in Australia of a new political culture – dominated by a relentless 24-hour news cycle and the power of special interests, especially trade unions – the path to further necessary liberal economic reform was blocked. As a consequence of all this, Australia had taken the first step onto “the escalator” of decline.

There are several problems with Kelly’s interpretation of the Rudd and Gillard years – in essence, the failure of Labor and its betrayal of the nation. One is Kelly’s consistent conflation of the problem of Rudd with the crisis of Labor. Another is the juxtaposition throughout of perceptive analysis and specious pontification. The clearest example of both problems comes from Kelly’s account of Kevin Rudd and the politics of climate change.

Kelly is sharp and convincing in his version of Rudd’s many climate-change missteps: his inopportune failure to close a deal with Malcolm Turnbull; his inability to resist the temptation to deepen divisions within the Coalition when he ought to have known that climate-change bipartisanship was vital; his comprehensive lack of courage when the prospect of a successful double-dissolution election beckoned; his psychological paralysis following the ascension of the denialist Abbott and the collapse of his grandiose hopes for the outcome of the Copenhagen climate conference; and the irreparable damage done to his reputation by his willingness to postpone action on the “greatest moral challenge” of the era.

The combination in Triumph and Demise of the shrewdness of the historian and the portentousness of the opinion columnist is truly disconcerting. Kelly embellishes his compelling analysis of Rudd’s climate-change disasters with an arrogant and foolish running commentary on climate change itself. Kelly must know that almost every scientist working in the field of climate, almost every national scientific institute and almost every major international institution – from the World Bank to the International Energy Agency – now regards the burning of fossil fuels as a potentially catastrophic threat to the future of humankind and other species.

Nonetheless, on dozens of occasions Kelly spices his narrative with irrational pronouncements from the songbook of climate-change denialism. He thinks that the warnings of the scientists are “alarmist”; that the problem of climate change is self-evidently not “a moral issue”; that climate change has become a Labor “faith”; that imagined catastrophes in the future provide “a poor basis for policy action now”; that only a political “mug” would call upon people to make a “sacrifice” for future generations; and, flatly, that “climate change was the priority for neither Australia nor the world at this point”. Not one of these statements is justified by argument. All reveal a profound ignorance of the work of climate scientists and its implications. All rest on nothing better than the prejudices of the contemporary Anglophone right. Not one could survive in a public debate outside the sheltered ideological workshop that now exists at the Australian.

Intelligent visitors to Australia, like the economist Joseph Stiglitz, greatly admire a government that successfully avoided recession during the global financial crisis. Kelly’s view is different. On balance, he is critical of both the size and the duration of the Keynesian stimulus, and gives Labor remarkably little credit for its economic management. Like most standard Australian conservatives, he underestimates the courage of Rudd’s stimulus decisions of 2008 and beyond, and vastly exaggerates the dangers of the relatively modest deficits the stimulus spending bequeathed. Throughout Triumph and Demise, Kelly castigates the government for its supposed failure to join the march of patriots on the road of economic reform. This is unjust, given the challenge of the global financial crisis, but it is more than that. In Kelly’s world, the very concept of reform has been so narrowed that it includes nothing other than measures to improve economic growth and productivity of the kind introduced during the Hawke and Keating years. Kelly seems to have forgotten what he once knew: that since World War Two Australia has had not one but two great reforming governments – first that of Gough Whitlam, and then that of Hawke and Keating. Because of Whitlam’s reforms – like the expansion of higher education and the introduction of universal healthcare and the championing of indigenous land rights – Australia became a profoundly better country. For Kelly, the adjective “Whitlamite” has been stripped of its connection to the idea of social justice and reduced to a synonym for fiscal recklessness.

By narrowing the idea of reform until it concerns nothing but the economy, and by transforming the idea of Whitlamism from achievement to accusation, Kelly manages to reduce the highly significant social reforms introduced during the Gillard years – Gonski in education and national disability insurance – either to marginal importance or to instances of future fiscal irresponsibility. Because Kelly is blithely unconcerned about inequality, he also appears uninterested in reforms aimed at reducing welfare to the upper middle class – like superannuation concessions to the wealthy, negative gearing, and generous subsidies to private schools and health insurance. Indeed, the only kind of economic reforms he now embraces are the “end of the age of entitlement” attacks on social welfare launched in the recent budget, which aim to reduce support for the despised groups that Joe Hockey calls the “leaners” and Rupert Murdoch the “scroungers”. Kelly characterises any interest in the problem of inequality as class warfare and the politics of social envy. At one point, even more revealingly, he describes Wayne Swan’s “focus” on “disadvantage” as an example of Labor’s regrettable reversion to class-based traditionalism.

The most obvious flaw in Triumph and Demise, however, is Kelly’s justification of News Corp’s war on both Rudd and Gillard, and his astonishingly dishonest pretence that it was not a principal cause of Labor’s prolonged crisis. Kelly does not tell his readers, for example, that on almost every day of the six-week period of the multi-million-dollar advertising blitz against the Rudd government’s proposed mining tax, the front page of the Australian was given over to anti-Labor propaganda from BHP Billiton and the Minerals Council. Nor does he mention that in late April or early May 2011 Rupert Murdoch met with the editors and leading journalists of his Australian newspapers at Carmel, California, and, according to one attendee, told them of his determination to bring about the end of the Gillard minority government.

At the time of the Carmel meeting, the Gillard government was considering the long-delayed legislative response to the problem of climate change. During the months that a committee of Labor, Greens and independent parliamentarians deliberated – February to July 2011 – 82% of News Corp’s articles on climate change were opposed to a price on carbon. The hostility of their opinion columnists was even more extreme. Once the policy was announced, hundreds of articles, frequently vicious, were written by News Corp journalists castigating “Ju-liar” Gillard for breaking her pre-election promise not to introduce a carbon tax. The anti-Labor campaign continued until the election of September 2013.

The atmosphere inside News Corp by mid 2013 is nicely captured in Rules of Engagement, the recent memoir of News Corp’s former CEO Kim Williams. Williams accepted the invitation to launch a book written by Rudd’s new treasurer, Chris Bowen. All hell broke loose among Williams’ enemies in News Corp, who seized their opportunity. Shortly after, he was personally sacked by Rupert Murdoch. Williams had failed to grasp that News Corp’s political mission was to destroy Labor. His naivety was strange. Shortly before Williams launched Bowen’s book, Murdoch had tweeted: “Australian public now totally disgusted with Labor Party wrecking country with it’s [sic] sordid intrigues. Now for a quick election.” There is in Triumph and Demise an unintentionally revealing anecdote. At Kirribilli, Kevin Rudd insisted that he finish telling a story before allowing Rupert Murdoch to take his leave. The News Corp editors in attendance were amused at the prime minister’s impertinence, his commission of the crime of lèse-majesté against the great man. This is the only time in Kelly’s 500-page book that Murdoch’s role in Australian affairs is mentioned. A history of the Rudd and Gillard years without the influence of Murdoch is less Hamlet without the Prince than Othello without Iago.

George Orwell once wrote: “He who controls the past controls the future. He who controls the present controls the past.” These words do not apply merely to totalitarian societies. With its control of two thirds of the metropolitan press in Australia, News Corp already exercises undue influence over the way daily politics is interpreted and values shaped in this country. With the publication of Triumph and Demise, written by the Murdoch empire’s most authoritative Australian voice, there is a good chance that it will now exercise, in addition, undue influence over the interpretation of our recent past. For this reason if for no other, Paul Kelly’s superficially plausible but stridently partisan and ideologically loaded history of the Rudd and Gillard years must be vigorously contested.

Robert Manne is Emeritus Professor and Vice-Chancellor’s Fellow at La Trobe University and has twice been voted Australia’s leading public intellectual. He is the author of Left, Right, Left: Political Essays, 1977–2005 and Making Trouble.

- By John Richardson at 6 Oct 2014 - 3:22pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

5 hours 13 min ago

9 hours 32 min ago

14 hours 54 min ago

16 hours 48 min ago

18 hours 16 min ago

20 hours 11 min ago

20 hours 58 min ago

1 day 12 hours ago

1 day 12 hours ago

1 day 13 hours ago