Search

Recent comments

- sad sy....

6 min 52 sec ago - terrible pollies....

16 min 47 sec ago - illegal....

1 hour 28 min ago - sinister....

3 hours 50 min ago - war council.....

13 hours 35 min ago - flying saucers....

13 hours 46 min ago - casualties....

13 hours 58 min ago - dystopian....

14 hours 57 min ago - losses....

15 hours 47 min ago - board of war....

17 hours 9 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

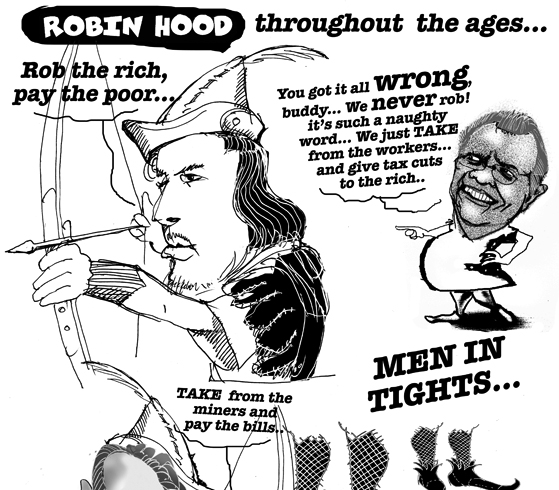

robbing the poor to pay croesus...

- By Gus Leonisky at 21 Mar 2017 - 6:43am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

money and happiness...

This is not a new philosophical debate...

According to Herodotus, Croesus encountered the Greek sage Solon and showed him his enormous wealth.[10] Croesus, secure in his own wealth and happiness, asked Solon who the happiest man in the world was, and was disappointed by Solon's response that three had been happier than Croesus: Tellus, who died fighting for his country, and the brothers Kleobis and Biton who died peacefully in their sleep after their mother prayed for their perfect happiness because they had demonstrated filial piety by drawing her to a festival in an oxcart themselves. Solon goes on to explain that Croesus cannot be the happiest man because the fickleness of fortune means that the happiness of a man's life cannot be judged until after his death. Sure enough, Croesus' hubristic happiness was reversed by the tragic deaths of his accidentally-killed son and, according to Critias, his wife's suicide at the fall of Sardis, not to mention his defeat at the hands of the Persians.

The interview is in the nature of a philosophical disquisition on the subject "Which man is happy?" It is legendary rather than historical. Thus the "happiness" of Croesus is presented as a moralistic exemplum of the fickleness of Tyche, a theme that gathered strength from the fourth century, revealing its late date. The story was later retold and elaborated by Ausonius in The Masque of the Seven Sages, in the Suda (entry "Μᾶλλον ὁ Φρύξ," which adds Aesop and the Seven Sages of Greece), and by Tolstoy in his short story Croesus and Fate.

read more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Croesus