Search

Recent comments

- UK kills russians...

3 hours 49 min ago - fury shit....

3 hours 59 min ago - epic diarrhoea....

4 hours 25 min ago - deceit...

16 hours 56 min ago - MbS's trap....

21 hours 25 min ago - mooning.....

1 day 2 hours ago - EU gas storage....

1 day 6 hours ago - wrong trousers....

1 day 6 hours ago - failure.....

1 day 6 hours ago - remembering....

1 day 8 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

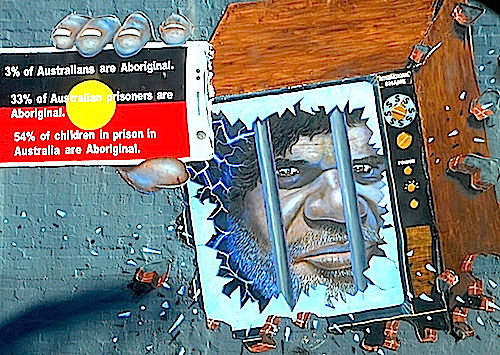

australia's shame...

shame

shame

- By Gus Leonisky at 29 May 2021 - 9:06pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

human rights...

Countries should unite against China's growing economic and geopolitical coercion or risk being singled out and punished by Beijing, former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd has told the BBC.

Mr Rudd said governments in the West should not be afraid to challenge China on issues such as human rights.

Around the world, countries are navigating a new geopolitical order framed by the rising dominance of China.

"If you are going to have a disagreement with Beijing, as many governments around the world are now doing, it's far better to arrive at that position conjointly with other countries rather than unilaterally, because it makes it easier for China to exert bilateral leverage against you," Mr Rudd told the BBC's Talking Business Asia programme.

His comments come as relations between Australia and China have deteriorated to their worst point in decades. The relationship has soured following a series of economic and diplomatic blows dealt by each side.

Australia has scrapped agreements tied to China's massive infrastructure project, the Belt and Road Initiative. It also banned Chinese telecommunications firm Huawei from building the country's 5G network.

But it was really Australia's call for an investigation into the origins of the coronavirus pandemic that set off a new storm between the two sides.

China retaliated by placing sanctions on Australian imports - including wine, beef, lobster and barley - and has hinted more may come.

Beijing has also suspended key economic dialogues with Canberra, which effectively means there is no high-level contact to smooth things out.

A new battlegroundMr Rudd, who led Australia twice between 2007 and 2013, has criticised the current government's approach to China, saying that it has been counterproductive at times.

"The conservative government's response to the Chinese has from time to time been measured - but other times, frankly, has been rhetorical and shrill," said Mr Rudd, who is now president of the Asia Society Policy Institute.

The former Labor party prime minister believes it could risk the fortunes of a key Australian export to China: iron ore.

"They [the Chinese leadership] will see Australia as an unreliable supplier of iron ore long term, because of the geopolitical conclusions that Beijing will make in relation to… the conservative government in Canberra.

Read more:

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-57264249

MEANWHILE:

Jacinda Ardern's government will come under increasing pressure to muscle up to China as relations with the superpower return to the fore.

Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison is sure to push the issue with New Zealand's leader when he visits Queenstown for talks with Ms Ardern on the weekend.

AAP can reveal dissent in Wellington, with MPs across the political spectrum dissatisfied with the government strong-arming a debate on Chinese human rights abuses.

This month, Labour used its majority in parliament to water down a proposed debate on whether atrocities committed against Uighurs in Xinjiang constituted genocide.

Instead, the parliament unanimously passed a motion condemning "severe human rights abuses".

One major party MP described that as "weak as water".

Another said the government was "totally beholden to China on trade".

"It's wholeheartedly ironic the debate was suppressed ... I think we will find that the parliament will have to revisit this issue again," another MP said.

Wellington is proud and protective of its relationship with Beijing, which produced China's first free trade agreement with a western nation, and which has not degraded in recent years as Sino-Australia relations have.

Still, China's embassy in Wellington "deplored" the parliamentary vote, saying it "will go nowhere but to harm the mutual trust between China and NZ".

Soon, Kiwi MPs may add their names to their dissent by joining the hawkish Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC).

IPAC is a growing group of MPs in western countries, including Australia, that want western governments to push China harder to admit abuses and change its behaviour.

NZ has just two members; co-chairs National MP Simon O'Connor and Labour MP Louisa Wall.

Read more:

https://au.sports.yahoo.com/zealand-braces-china-storm-014644022.html

And while you're on the subjects of human rights, FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW %%%% and contemplate the picture above...

deaths in custody

Last week, 43-year-old Frank Coleman became the ninth Aboriginal person to die in police or prison custody since March.

Key points:Warning: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that this article contains images of a person who has died.

His family say the regularity of such deaths is "incomprehensible" but they do not want the proud Ngemba man to be reduced to another statistic.

"He was an individual," said former partner Skye Hipwell.

"He deserves to be known as an individual, and this needs to be treated as an individual case."

Daughter Lakota Coleman wants to remember her father's infectious energy and his ability to win people over.

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-07-16/frank-coleman-family-aboriginal-deaths-in-custody/100296982

Read from top.

not closing yet...

Indigenous people are still far more likely to be jailed, die by suicide and have their children removed than non-Indigenous people a year after the new Closing the Gap agreement was signed, according to the Productivity Commission.

The Commission today released its first batch of annual data on the National Agreement on Closing the Gap.

But it can’t say how progress on ten of the 17 targets is going due to a lack of new figures to compare against the baseline data being used.

“The Agreement is now 12 months old, but the most recent available data for monitoring these socioeconomic outcomes are only just hitting the commencement date for the Agreement,” commissioner Romlie Mokak said.

“It is likely to be some years before we see the influence of this Agreement on these outcomes.”

The federal, and state governments - alongside 50 peak Indigenous organisations - reached a historic agreement to address the inequality faced by First Nations people last July.

The new National Agreement on Closing the Gap is intended to be a proper partnership, to move beyond what Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt described as a decade of failings.

Among its 17 ambitious targets, the Agreement is aiming to reduce the Indigenous incarceration rate by 15 per cent in the next decade.

But the Productivity Commission’s report said the rate of Indigenous prisoners rose from 2077.4 per 100,000 people in 2019, to 2081 in June 2020.

Read more:

https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/closing-the-gap-indigenous-suicide-and-incarceration-rates-rising-20210728-p58dkw.html

Read from top.

criminal? kids...

SPECIAL INVESTIGATION: Data from Australia’s criminal justice system shows clearly that we’re failing to rehabilitate children, while making them more likely to reoffend. And yet kids as young as 10 are still being charged with criminal offences. Warwick Jones investigates.

A 10-year-old Aboriginal girl wearing pigtails and a school uniform walks into the Geelong Children’s Court, dwarfed beside two welfare workers. It’s late autumn, 2015. The girl’s been taken out of her grade four class to come before the court charged with stealing a phone.

She’d been removed from her family home and placed into state care. On the day of the alleged offence she was found in a neighbour’s car trying to call her mum.

The girl’s lawyer, Mr Ali Besiroglu, is at the time a senior solicitor at the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service. He’s also a father to three kids not much younger than his client.

Besiroglu pleads with the police prosecutor to withdraw the case, but he refuses. So while they’re waiting for the magistrate, Besiroglu walks his client over to the prosecutor’s table and introduces him to the young girl he has up until this point only read about.

“This man is the prosecutor,” Besiroglu tells her. “He’ll be talking to the magistrate. The magistrate will sit up there,” Besiroglu points to the bench, “he’ll decide what happens here today. We’ll sit over there, and I’ll be telling the magistrate your side of the story.”

The prosecutor is polite to the girl. But he is angry at Besiroglu. “Why’d you have to pull that stunt?” he asks once the girl left. But it’s not a trick. The decision to prosecute a 10-year-old child shouldn’t be easy.

“Her case clearly highlighted to me that there needs to be reform,” Besiroglu said. “She was so small, she was scared, she was confused, and it was clear to me that whatever conduct she had engaged in, it wasn’t criminal.”

And Besiroglu is far from alone. In courthouses and legal chambers around the country the conversations are the same. Young children should not be in the criminal justice system.

Get them while they’re young

IN VICTORIA, the law allows for children as young as 10 to be charged with a crime, brought before the court, and locked up. The age a child can be held criminally responsible in every Australian state and territory is 10 — one of the lowest in the Western world and in breach of international human rights law.

In May, Victoria’s Youth Justice Minister, Ben Carroll, released a strategic plan outlining the state government’s 10-year vision for the youth justice system. The plan aims to reduce the number of young people in the system and improve community safety.

But the 53-page document makes no commitment to raise the age of criminal responsibility, instead abdicating the decision to the Council of Attorneys-General who are currently reviewing the age.

Yet there is a unified voice amongst experts calling for the government to raise the age of criminal responsibility. Smart Justice for Young People — which represents more than 40 legal, social, and health organisations in Victoria — is calling for the age to be raised to at least 14. As are academics, child’s rights groups, and Children’s Commissioners around the country.

Today, kids under 14 who are brought before the courts are presumed to be ‘doli incapax‘ — that is, they don’t have the capacity to commit crime because they lack a guilty mind. It’s up to the prosecution to prove that the child knew that what they were doing was seriously wrong.

Read more:

https://newmatilda.com/2020/06/28/the-child-inside-in-australia-we-prosecute-10-year-olds-especially-if-theyre-black/

Read from top.

not only in australia...

This spring, the Biden administration announced it would seek public comment on student race and school climate, which was roundly viewed as a precursor to restoring an Obama-era directive to reduce racial disparities in discipline practices. Those guidelines, which were rescinded by former Secretary Betsy DeVos, have been variously described as a critical means of protecting students’ civil rights and a dangerous overreach by the federal government that prevented schools from keeping students safe.

At issue is the school-to-prison pipeline—a term often used to describe the connection between exclusionary punishments like suspensions and expulsions and involvement in the criminal justice system. Black and Hispanic students are far more likely than white students to be suspended or expelled, and Black and Hispanic Americans are disproportionately represented in the nation’s prisons.

Is there a causal link between experiencing strict school discipline as a student and being arrested or incarcerated as an adult? Research shows that completing more years of school reduces subsequent criminal activity, as does enrolling in a higher-quality school and graduating from high school. Yet there is little evidence on the mechanisms by which a school can have a long-run influence on criminal activity.

To address this, we examine middle-school suspension rates in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, where a large and sudden change in school-enrollment boundary lines resulted in half of all students changing schools in a single year. We estimate a school’s disciplinary strictness based on its suspension rates before the change and use this natural experiment to identify how attending a stricter school influences criminal activity in adulthood.

Our analysis shows that young adolescents who attend schools with high suspension rates are substantially more likely to be arrested and jailed as adults. These long-term, negative impacts in adulthood apply across a school’s population, not just to students who are suspended during their school years.

Students assigned to middle schools that are one standard deviation stricter—equivalent to being at the 84th percentile of strictness versus the mean—are 3.2 percentage points more likely to have ever been arrested and 2.5 percentage points more likely to have ever been incarcerated as adults. They also are 1.7 percentage points more likely to drop out of high school and 2.4 percentage points less likely to attend a 4-year college. These impacts are much larger for Black and Hispanic male students.

We also find that principals, who have considerable discretion in meting out school discipline, are the major driver of differences in the number of suspensions from one school to the next. In tracking the movements of principals across schools, we see that principals’ effects on suspensions in one school predicts their effects on suspensions at another.

Our findings show that early censure of school misbehavior causes increases in adult crime—that there is, in fact, a school-to-prison pipeline. Further, we find that the negative impacts from strict disciplinary environments are largest for minorities and males, suggesting that suspension policies expand preexisting gaps in educational attainment and incarceration. We do see some limited evidence of positive effects on the academic achievement of white male students, which highlights the potential to increase the achievement of some subgroups by removing disruptive peers. However, any effort to maintain safe and orderly school climates must take into account the clear and negative consequences of exclusionary discipline practices for young students, and especially young students of color, which last well into adulthood.

Read more:

https://www.educationnext.org/proving-school-to-prison-pipeline-stricter-middle-schools-raise-risk-of-adult-arrests/

Read from top.

SEE ALSO:

imprisonment...FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!

lack of care....

Lucy* was scrolling through Facebook when she suddenly discovered her daughter had died by suicide.

WARNING: This story contains details that readers will find distressing.

"I read that my daughter was deceased and I screamed and I couldn't breathe," she said.

"I tried to get hold of people and I couldn't get hold of anybody and it was just sitting and waiting … all night, to find out whether it was the truth and what had happened to my baby."

Lucy's teenaged daughter, Courtney*, was in Victoria's residential care system at the time, having been taken from Lucy several years ago by authorities due to safety concerns.

Lucy, an Aboriginal woman, said she had been in an abusive relationship back then, one which she had since managed to escape.

The ABC understands Courtney's primary family contact during her time in care was a different relative to Lucy.

Lucy is angry her daughter died in the care of a department that she feels failed to offer "proper care", and is hoping a coronial inquiry into Courtney's death will ensure other families don't experience the same grief she now carries.

It's a grief that was compounded by the fact that she first discovered the death after Victoria Police amended a missing persons alert about her daughter, before officers had visited her home to break the news.

The ABC understands Victoria Police Chief Commissioner Shane Patton apologised over the matter to the state's Aboriginal Justice Caucus.

Lucy said the Department of Fairness, Families and Housing later reached out to her.

"They apologised and I was very angry that my daughter had lost her life in their care and [the representative] had no understanding," she said.

"And then they sent flowers ... that I threw in the bin."

Another shock lay in wait for Lucy, as she discovered her daughter had been battling severe mental health issues for months, including a previous suicide attempt.

"I had no idea that [Courtney] had tried to take her life before. If I'd known so I would have tried to be in her life more and I would have checked on her more," Lucy said.

"That's their role, that's why I thought she was OK.

"Their care of duty as adults and people who took her from me is to look after her."

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-20/aboriginal-girl-suicide-residential-care-victoria/100380604

Read from top.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW...

under the guise of protection...

Indigenous Australians are controlled by the criminal system under the guise of protection

Carly Stanley for IndigenousX

Policies that continue to disproportionately inflict violence and disruption on First Nations people show we are still a penal colony

First Nations people and communities are the most legislated group within Australia. From the time the first fleet arrived, our mob has been controlled under the guise of protection. Australia was invaded and utilised as a penal colony, and we continue to be a penal colony to this day.

Policies of “protection” were enacted across Australia which demanded complete government control over all aspects of the lives of Aboriginal people including the removal of First Peoples from their homelands and Country on to missions and reserves. While Indigenous people were being controlled under the facade of protection, our mob were not yet intimately acquainted with criminal systems. Police played a key role in enforcing protection legislation. The policies and practices of protection, assimilation and child removal were deeply rooted in racist beliefs and left a legacy of grief, loss and trauma that continues to impact on First Nations people, families and communities today.

While the historical era of “protection” has dissipated, such controls have manifested in new forms through our legal systems. The racially driven and carceral nature of missions and reserves was gradually superseded by the institutional growth of the child protection, youth and adult “injustice” systems. Systems that continue to disproportionately inflict violence, disruption and devastation for First Nations people, families and communities.

Currently, First Nations people are 17 times more likely to be under child protection supervision than non-Aboriginal families and the numbers of Aboriginal children in out of home care is projected to double in size by 2028. Not only are First Nations people arrested at unacceptably high rates, we are imprisoned at the highest rate in the world.

Although First Nations adults consist of around 3% of the national population, our people constitute 27% of Australia’s national prison population. Disproportionate rates of imprisonment have continued to rise despite declining rates of crime.

While the primary drivers for mass incarceration are often external to the criminal legal system, where extreme levels of poverty, disadvantage and trauma contribute to the elevated levels of justice system involvement for First Nations people and communities, the system is also to blame. Structural racism and bias is evident at every facet of the legal system and disproportionately affects First Nations people. Every single step taken by a First Nations person through the criminal legal system is unjust. Aboriginal people are much more likely to be questioned by police, more likely to come to the attention of police, more likely to be arrested rather than proceeded against by summons. If arrested, we are more likely to be remanded in custody than given bail and more likely to plead guilty than go to trial, and if we go to trial, we are more likely to be convicted. If convicted, we are more likely to be imprisoned, and at the end of the term of imprisonment we are less likely to get parole.

Understanding and truth telling about the nexus between racism, structured segregation, government modes of control and regulation is critical to addressing the hyper incarceration of First Peoples of Australia in the current criminal legal system.

The culmination of lived and professional experience of my husband Keenan Mundine and me, coupled with the ineffectiveness of the current colonial systems that are in place and the ongoing harm and violence experienced by our communities, inspired us to establish an organisation that addresses the effects of systemic racism, trauma, disadvantage, and poverty on the mass incarceration and over-representation of First Nations people in the justice and child protection systems.

Deadly Connections was established to provide culturally safe advocacy, support, information, referrals and programs for First Nations people, families and communities. In Aboriginal English, “deadly” means excellent or really good. Deadly Connections focuses on promoting healing and justice by implementing alternative justice solutions that focus on transformative justice and community driven initiatives. Our work aims to positively disrupt the intergenerational disadvantage, grief, loss, and trauma of First Nations people by providing holistic and culturally responsive services.

Being a part of the UNHEARD campaign is a critical step in highlighting the needs for organisations like Deadly Connections, addressing racism, inequity and social justice issues, into the wider domain for the public to see and understand. By engaging in an initiative like this we can amplify our voices and the voices of other mob, to raise awareness and support for much needed changes to the system/s that continue to harm, oppress, marginalise and disenfranchise our people, families and communities.

Carly Stanley is CEO and co-founder of Deadly Connections. She is a proud Wiradjuri Woman, born and raised on Gadigal land.

Read more: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/nov/04/indigenous-australians-are-controlled-by-the-criminal-system-under-the-guise-of-protection

Read from top.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

trailblazing...

At just 17 years old, when David Dalaithngu first touched down in Europe, he was the toast of the town — a young, handsome Aboriginal film actor from the remote Northern Territory who could hardly speak English.

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains an image of a person who has died.

The cameras adored him and the fans flocked to catch sight of this new star.

Nearly five decades later, the world now bids farewell to a prolific trailblazer who walked tall in two cultures and starred in landmark Australian films Crocodile Dundee, Rabbit Proof Fence, Storm Boy, Walkabout, The Tracker and many more.

Dalaithngu was better known by a different surname at the height of his stardom, but the ABC has been advised that for Indigenous cultural reasons that name can't be used.

The Yolngu actor, dancer and painter from Arnhem Land died at the age of 68.

Several years ago, Dalaithngu had been diagnosed with lung cancer. He was a resident of Murray Bridge in South Australia.

In a rollercoaster career spanning from 1971 to 2018, Dalaithngu transformed Australian cinema.

He opened the eyes of audiences across the Western world to strong, positive depictions of Aboriginal Australia and eventually became, as Rabbit Proof Fence director Phillip Noyce once dubbed him, "arguably the most experienced and accomplished film actor in Australia".

Read more:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-11-30/aboriginal-actor-yolngu-david-dalaithngu-crocodile-dundee-dies/8468524

I had the privilege of seeing David Dalaithngu's one-man show at the Belvoir Theatre. A treat of honesty, comedy, very enlightened social comments and tragedy.

Read from top.