Search

Recent comments

- midterms....

36 min 26 sec ago - stupidly....

55 min 3 sec ago - lucky not....

1 hour 28 min ago - training murderers....

1 hour 10 min ago - crafted in gaza.....

1 hour 30 min ago - beautiful murders....

3 hours 45 min ago - revisited....

7 hours 30 min ago - a major failure....

7 hours 58 min ago - minitel 2.0?

9 hours 7 min ago - running out....

9 hours 11 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

why trump was shut down by big tech...

pitin

pitin

Hey all, it’s Kurt. Donald Trump built his presidency on platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Google’s YouTube. But times have certainly changed. On Wednesday, Trump sued all three companies, and their respective chief executive officers, claiming they violated the First Amendment by banning or suspending his accounts following the Jan. 6 Capitol riots.

On the surface, a former U.S. president personally suing the CEOs of some of the country’s largest technology companies sounds like a huge deal. As with many things Trump, the reality is more subdued.

The lawsuits—there were technically three separate filings—were quickly dismissed by industry experts. The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University called the suits “a stunt.” Paul Barrett, a former Bloomberg journalist and the deputy director of the NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights, said the lawsuits were “DOA.”

“I’ll be filing a class action suit against Trump for unconstitutionally wasting everyone’s time,” tweeted Kate Klonick, who teaches law and technology at St. John’s University.

At their core, Trump is asking the court to reverse Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which shields tech platforms from lawsuits over the content their users post. Trump called the protections an “unconstitutional delegation of authority,” and said the companies infringed upon his right to free speech by removing his accounts.

But social media companies are not government agencies, and thus have their own First Amendment rights to run their platforms as they deem necessary, Barrett explained in an interview.

“The First Amendment regulates how the government can deal with free speech,” he said. “It does not regulate how private companies regulate free speech.” He predicted that the lawsuits will be thrown out at the “preliminary stage.”

So why is Trump suing Facebook Inc., Twitter Inc. and Google six months after he was first suspended from their platforms if he doesn’t have much chance of winning?

Reporters were quick to point out that Trump was using the lawsuits to help with fundraising as early as Wednesday morning, asking people to “contribute IMMEDIATELY” to help with his lawsuits against “UNFAIR CENSORSHIP.” It’s highly possible that Trump has further political ambitions, and a splashy, public lawsuit against the world’s largest tech companies is an easy way to rally his supporters and raise some money.

Then there’s a second Trump tactic at play, Barrett said, and that’s his ability to distract. It was just last week that the Trump Organization’s longtime chief financial officer pleaded not guilty to federal indictment charges.

“With Trump, timing is often relevant,” Barrett said. “With one controversy, [Trump] is trying to distract you from yesterday’s controversy.”

Which means that there are indeed a few good reasons for Trump to unveil some splashy lawsuits this week. A violation of the First Amendment just isn’t one of them. —Kurt Wagner

Read more:

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2021-07-08/what-s-behind-trump-s-big-tech-lawsuit

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

- By Gus Leonisky at 13 Jul 2021 - 2:09pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

ROLF...

rolling on the floor laughing...

In 2016, the German historian and political philosopher Jan-Werner Müller published “What Is Populism?,” a well-timed examination of rising political movements, from the United States to India. He also offered a new definition of the term, proposing that populist leaders are defined less by anti-élitist rhetoric than they are by their insistence that they represent an unheard majority of the people.

Müller has now followed this work with a new book, “Democracy Rules,” which looks at the ways democracy has been weakened over the past several decades, and offers solutions for insuring its survival. “This can be done without simply reinstating traditional gatekeepers,” he writes. “The people themselves are able to determine the ways in which intermediary institutions—parties and media, above all—should be refashioned.”

I recently spoke by phone with Müller, who is a professor of politics at Princeton. During our conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity, we discussed whether it makes sense to lay blame for populism’s rise at the feet of voters, the best ways to preserve democracy going forward, and whether right-wing populism can exist without bigotry.

Given the ways the world has changed over the past five years, has your conception of populism changed as well?

My understanding of populism has always deviated somewhat from the inherited American understanding of that term, which goes back to the late nineteenth century, and the sense that it is about Main Street versus Wall Street. Partly against the background of a European understanding of politics, I essentially want to argue that populism is really not just about criticizing élites or being somehow against the establishment. In fact, any old civics textbook would have told us up until recently that being critical of the powerful is actually a civic virtue, and now there’s much more of a sense that, well, this could actually somehow be dangerous for democracy.

So it isn’t as simple as that. It’s true that, when in opposition, populist politicians and parties criticize sitting governments and other parties, but for me what’s crucial is that they tend to allege that they and only they represent what they often call the “real people” or, also very typically, the “silent majority.” That might not sound so bad, that might not sound immediately like racism or fanatical hatred of the European Union or anything of that sort.

It doesn’t sound great.

No, it doesn’t sound great, but it’s not immediately obvious where the danger is. But it indeed does have two detrimental consequences for democracy. The obvious one is that populists are going to claim that all other contenders for power are fundamentally illegitimate. This is never just a disagreement about policies or even about values, which after all in a democracy is completely normal, ideally maybe even somewhat productive. No, populists always immediately make it personal and they make it entirely moral. This tendency to simply dismiss everybody else from the get-go as corrupt, as not working for the people, that’s always the pattern.

Then, second, and less obviously, populists will also suggest that anybody who doesn’t agree with their conception of the real people, and therefore also tends not to support them politically—that with all these citizens you can basically call into question whether they truly belong to the people in the first place. We’ve seen this with plenty of other politicians who are going to suggest that already vulnerable minorities, for instance, don’t truly belong to the people.

Long story short, for me populism isn’t about anti-élitism. Any of us can criticize élites. It doesn’t mean we’re right, but this is not in and of itself anything dangerous for democracy. What’s dangerous for democracy, and what I take to be critical to this phenomenon, is basically the tendency to exclude others. Some citizens don’t truly belong, and we see the consequence of that on the ground in India and Turkey and Hungary and in many other countries.

What about left-wing populism, which, as it’s generally understood, does not try to marginalize people by saying they’re not true members of the real people?

Again, I think it’s not about the criticism of élites as such. This is something that’s completely normal and completely fine within a democracy for left-wing actors. The crucial thing is, How do they talk about people who disagree with them? Do they argue with them, argue against them, but accept them as legitimate players in the democratic game, or do they essentially argue, No, these people shouldn’t be in the game in the first place? Lots of movements and parties which are today labelled as left-wing populism, let’s say Podemos, in Spain, or Syriza, in Greece, one doesn’t necessarily have to like their policies, but for me to put them in the same category as Marine Le Pen or for that matter in the same category as Chávez and Maduro, for whom it was clear after a certain point, there cannot be anything like a legitimate opposition—I know that these distinctions can be hard to pin down, there might be hard cases, but I think in many, many instances, you can tell whether somebody is essentially simply trying to discredit their adversaries completely.

You write that one response people have had to elections over the past five years is to blame the people who voted in Trump or Modi or Bolsonaro. You say that that’s the wrong way to go about this. I understand that if you’re a politician you don’t want to say that the people whose votes you need are stupid, but why is it wrong for people to blame voters for the choices they make, and isn’t that in a way respecting their choices?

Any of us can criticize the decisions of voters and, with regard to some of the leaders you just mentioned, there’s obviously plenty to criticize. My concern is that—how to put this politely—for a certain type of liberal, this has sort of opened the floodgates for basically indulging a lot of clichés from late-nineteenth-century mass psychology in terms of, oh, of course we always knew the people are so irrational, they’re always waiting for the great demagogue to seduce them. We need more professionalism, we need more gatekeepers, and so on.

I think that’s politically problematic because it violates a basic intuition about democratic equality, but then obviously I think it misunderstands how a lot of these outcomes came about. People, in some cases, at least, tend to project what happens later on back to the origins. One example, people say, Oh, in Eastern Europe, we all know that these people are probably more illiberal and they never understood multiculturalism. But if you look back on what actually happened about a decade ago, it’s not that Orbán stood there and said, Hey, vote for me, I’m going to disable the rule of law, I’m going to abolish media pluralism, I’m going to erect a plutocracy. He didn’t mention anything remotely radical in his election campaign that brought him to power for the second time. He didn’t even say he was going to change the constitution. Once he was in power, of course, many, many things happened, but then, in the next election, it’s already much harder for voters to come to truly informed judgments about some of what happens, plus many people are basically prevented from taking part in the first place. So I’m not saying voters are never to blame, but I think we need to be more careful in how we construct these stories.

One important point you make in the book is that many of these leaders have trouble winning majorities, and one of the reasons they make it harder for people to vote is that they’re afraid a majority in a fair election would not vote them back in. That’s not true in India right now, but it’s certainly true of many places.

That’s why the rhetoric you sometimes hear from these figures, that they’ve given power back to the people, that they have somehow reëstablished direct democracy, is false advertising. Yes, some of them engage in more or less fake national consultations—again, Orbán is a good example. You have completely manipulated questionnaires; it’s nothing like a free and open democratic process. Less obviously, when they have the chance to change the whole system of the constitution, they entrench their own preferences, making it more difficult for future majorities to change the course of a policy. They may well know that a lot of what they do isn’t genuinely popular, so all they can do is basically manipulate the system in their own favor.

What you said about Orbán and how he came to power is interesting, but maybe Trump is a good counter-example. Trump ran a reëlection campaign where he made very clear that he did not care about the fact that hundreds of thousands of people were dying, and he couldn’t be bothered by that. So it does seem to me that sometimes these figures are able to engage in a type of politics that is contemptuous of their voters or of the people and get away with it, or at least get forty-seven per cent of the vote.

I think one of the things that we perhaps by now should have learned is that the political business model of these figures is dividing the people as much as possible. So they create situations of extreme polarization, where at least some citizens feel they’re in a position where, even though they have some problems with the person who they think defends their interests, advances their ideas or even identity, to some degree, nevertheless the choice is still stark; they have to go with one side. Once the political field looks like that, yes, it’s much more likely that democracy in general is in danger, that people get reëlected even though plenty of people actually feel queasy about these figures.

Now, ultimately, once you’ve reached that point, what I just said isn’t very helpful because you’re already there. But if earlier on there are ways of saying, Wait a minute, if there’s a move in that direction, we must do absolutely everything to prevent these outcomes, because that’s what the Chávezes and Orbáns and Modis and Trumps of this world have proven to us. So this is obviously why we’ve got to prevent these figures from implementing their full business model, which then results in this total division.

And this isn’t just about the cases of the individual leaders. It has a lot to do with what I try to analyze in the book as the larger infrastructure of democracy—the health and state of political parties, the health and state of professional news organizations, all those play a role. It’s not just about the psychology of either the leader or individual citizens. There are a lot of institutions and a lot that happens in between, and if you look most obviously at the state of the Republican Party, it didn’t just all start with Trump. But the fact that he was basically able to reshape the Party into a kind of personality cult, where no such thing as legitimate internal opposition or anything like critical loyalty was possible anymore, massively contributed to the kind of over-all polarization.

There was a big debate during the Trump years about whether his appeal was more about economic issues or racism in the electorate. Do you perceive there to be in existence right-wing populism that does not appeal in part to racial or ethnic or religious grievances?

I would say that nationalism and right-wing populism are still different phenomena, but it’s not an accident that, as you say, virtually all right-wing populists today happen to be basically far-right nationalists. You can be a nationalist without ever making this anti-pluralist claim in politics, that only you represent the people. That’s still a different thing. By the same token, in theory, you could be a populist who doesn’t draw on the nation as the most obvious source of describing the people, but it’s the one that’s most readily available, and that’s why most right-wing populists go for it at this point.

Furthermore, all populists, in my view, they’re all going to be anti-pluralists, but not all anti-pluralists are populists. So, if you are a theocrat or if you’re a Leninist, you’re also going to be pretty anti-pluralistic. It’s not like you’re going to have a very tolerant, open mind-set. But at the same time, what you don’t do is say anything positive about the people. So a populist, on one level, is still going to bring in the argument that the people are a source of wisdom, they can’t really go wrong, we are just implementing what they truly want. All the other crap politicians are not really following the lead of the people. If you’re a theocrat, you’re probably going to say, No, the people are sinful and fallen, and we as an élite of sorts have to rescue them. Or if you’re a Leninist you’re going to say, Look, the workers by themselves, all they’re going to ever get to is trade-union consciousness. They don’t understand how world history works, they don’t understand how to make a proper revolution, so we as a tiny vanguard that is unashamedly élitist are going to show them the way. So all that is anti-pluralism, but it’s by no means anywhere near populism.

You mentioned Trump and nationalism, but this was a guy who said that we’re no better than Russia, who repeatedly praised the Chinese Communist Party. It was this weird nationalism where he could basically say America was shit and get away with it.

I would say two things about this. A strategy to prove that you really are completely different from all the other career politicians is to break the occasional taboo or to say something that is really going to make people listen because all of a sudden you might say, Oh, that might actually be true, but nobody ever really said that to us. But think about the fact that even Democrats on all possible occasions underline that we have the greatest nation on earth, the greatest democracy, and so on. It’s always strange that you say that and in the next breath you say, But actually our infrastructure is horrible and we have all these problems. I think that actually has always been a strange combination for a party that nominally is on the center-left. But it can also, to many people, sound very sanctimonious. If somebody pricks this bubble and talks in a very different way, I think for some people it may have been genuinely refreshing. Obviously, it’s more complicated, because the same people ultimately still also believe in the superiority of the U.S.

How do you think this populism we are talking about can be combatted? It seemed to me that you have a certain frustration with people who see the solution as lying with existing institutions and gatekeepers. Is that fair?

Yes and no. We certainly do need to strengthen institutions, but not just the obvious textbook institutions of democracy. We also need to strengthen those which, I think it’s fair to say, ever since the nineteenth century, proved to be indispensable to actually make representative democracy as we know it work. So political parties and professional news organizations. It’s conventional wisdom that especially the latter are in crisis and that there are big transformations happening and that this somehow might have something to do with broader political pathologies, but too rarely do we actually think about how these institutions might have to look different, what standards they should fulfill to play a positive role in democracy as a whole. So I’m not dismissing institutions, but I think what I have less patience for is the hope that, Oh, if we have wise judges they will save us, or if we have other élites who will magically step in at the last minute, we can rely on them. I think that’s a much more problematic view.

Beyond that, yes, it does matter to mobilize majorities against right-wing populists in particular. There’s been great difficulty in this for many political parties, many of which—I mean not so much in Europe but in many other countries—became subject to a divide-and-rule strategy from populist leaders. Many of them took a long time to learn that you certainly have to criticize right-wing populists in power, especially the ones who are taking their countries down the path of autocracy, but you also somehow need to find a way to communicate to citizens that there’s a distinction between conduct that truly endangers democracy and run-of-the-mill policy disagreement.

Explain in practice how you view that distinction.

To say that the abolition of the Affordable Care Act somehow equals the end of democracy is the wrong way of framing things. Obviously, there are many good reasons to oppose what Republicans have been trying to do for many years, but to basically say that anything that a particular government does is in and of itself a full-scale attack on democracy only leads to an outcome where citizens say, Oh, whatever the government does, they’re always criticizing it; I’m not really listening anymore. I don’t really see the difference between what they now again find fault with and this other fault which they also constantly criticize.

This is also an issue for plenty of American journalists. They clearly saw that something was deeply troubling about Trump, but it would have been very helpful if they had made a clearer distinction between stuff that basically any Republican President would have tried and things that a more or less normal Republican President simply wouldn’t have done—to use a relatively mild example, trying to get rid of all inspectors general, basically trying to enable a certain kind of corruption in the Administration. Again, it’s not a hard-and-fast distinction. It’s not a science. But my worry is, if you don’t try to do that, you basically lose the attention of citizens, and eventually they don’t get the actual level of threat because the level of alarmism always seems to be the same.

I don’t disagree with that, but it seems slightly in tension with something you said earlier, namely that democracy in a place like the United States has weakened to the point where it’s vulnerable to someone like Trump, in part because of typical Republican Party policies and their long-term effects.

Of course Trump had a pre-history. This image was sometimes deployed that here was this stable ship that was nicely sailing on the calm seas of governance, and then this pirate shows up and hijacks the vessel and leads it into choppy waters. Obviously that’s very misleading, because at least since the nineteen-nineties, at least since Newt Gingrich basically handed out his list of words which always had to be used when describing Democrats—things like “betray,” not your run-of-the-mill democratic rhetoric when you disagree with your adversaries—all that paved the way.

Read more:

https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/redefining-populism

"Deplorables" comes to mind...

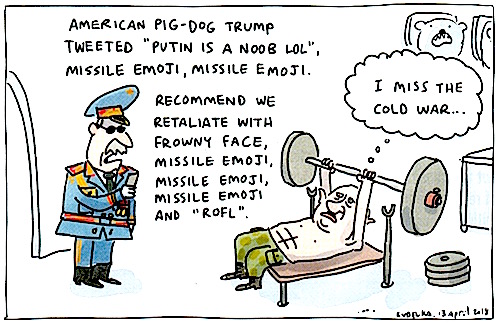

NOTE: I don't know who did the cartoon at top... I found it in a garbage bin and I thought it was funny. I rescued it and cleaned it... Emoji smile...

the good reasons why the "deplorables" still support trump...

From Glenn Greenwald.

NOTE FROM GLENN GREENWALD: On Friday, a relatively obscure Twitter user with fewer than 7,000 followers — posting under the pseudonym MartyrMade — posted one of the most mega-viral threads of the year. Over the course of thirty-five tweets, the writer, a podcast host whose real name is Darryl Cooper, set out to explain the mindset that has led so many Trump supporters to believe that the 2020 election was fraudulent and, more generally, to lose faith and trust in most U.S. institutions of authority.

Numerous journalists, including me, promoted the thread as one of the most insightful analyses yet published explaining the animating convictions underlying the MAGA movement. That night, Fox News host Tucker Carlson devoted a seven-minute segment to doing nothing more than reading Cooper’s thread. At the CPAC conference on Sunday, former President Donald Trump explicitly recommended the thread using Cooper’s name. In the last four days, Cooper’s Twitter account has gained more than 70,000 followers. Clearly, this thread resonated strongly with that political faction as a true and important explanation of how many MAGA voters have come to understand the world.

For our Outside Voices freelance section, we asked Cooper to elaborate on his influential thread, with a focus on what led him to these observations about prevailing MAGA sentiments and why he believes they are important for people to understand. As Cooper notes, he does not share all of the perceptions and beliefs he is conveying, although he shares many of them. Instead, based on the recognition that most media outlets are incapable of understanding let alone accurately describing the views of a group of people they view with little more than unmitigated contempt, condescension and scorn, he believes it is imperative that people understand the actual reality of what is motivating so many Trump voters in their views, perceptions and beliefs — regardless of whether each particular belief is accurate or not.

We also believe this understanding is vital, which is why we are happy to publish Cooper’s essay. It should go without saying that, as it true of all of our articles published on Outside Voices -- which we treat as an op-ed page -- our publishing of this article does not signify agreement with all of its claims, but only our belief that it is a viewpoint worth airing.

-----------------------

By Darryl Cooper

I quit Twitter last August. Quit for good. Other than posting links to two new episodes of my podcast, I stayed away for eight months and didn’t regret a thing. Around mid-June I let myself be persuaded that social media engagement was part of having a podcast, so I dipped back in, promising myself I’d avoid being pulled into politics. Things haven’t gone as planned.

The temptation was disguised cleverly as a conversation with a friend’s mother. She was visiting from upstate New York and we got to talking while my buddy was in the house tending to my goddaughter. She’s a hardcore Trumper from a less cynical generation that believes what she hears from sources she trusts. She’d been hounding her son about the stolen election all week, and he’d been trying to disabuse her of various theories involving trucked-in ballots and hacked counting machines. Now she had me cornered and put the question to me: “Do YOU think the election was legit?” So I told her the truth: I don’t know.

By the time my friend had put the baby to bed and rejoined us, we were waist-deep in a discussion about what happened last year, and she was satisfied that I was on her side. “See?!? He (she meant me) knows what’s going on! I’m not crazy. He’s smart, and HE knows!” My friend pulled the Captain Picard facepalm, and said, “Darryl, what the f*ck are you telling her?”

What I told her was some version of the Twitter thread Tucker Carlson read on air Friday night and which President Trump, using my name, then explicitly promoted in his speech to CPAC on Sunday, which has blown my inbox, and my promise to stay away from politics, to smithereens.

I told her I didn’t know much about the ballots, or the voting machines, or some company that she’d heard had ties to Venezuela. I didn’t follow Sidney Powell, or Lin Wood, or the details of the cases proceeding through the system. I think it was around the time Rudy Giuliani chose a landscape and gardening emporium as the location for a press conference on what would have been the greatest political scandal in American history that I made the conscious decision to stop paying attention. Or maybe it was the dripping hair dye, or something about a kraken — it’s all sort of blended together these days.

But I felt for her. She wasn’t the first person with whom I’d had the discussion, and I felt for all of them. I’ve had the discussion often enough that I feel comfortable extracting a general theory about where these people are coming from.

RUSSIAGATE: THE ORIGINAL SINLike my friend’s mother, most of them believe some or all of the theories involving fraudulent ballots, voting machines, and the rest. Scratch the surface and you’ll find that they’re not particularly attached to any one of them. The specific theories were almost a kind of synecdoche, a concrete symbol representing a deeply felt, but difficult to describe, sense that whatever happened in 2020, it was not a meaningfully democratic presidential election. The counting delays, the last-minute changes to election procedures, the unprecedented coordinated censorship campaign by Big Tech in defense of Biden were all understood as the culmination of the pan-institutional anti-Trump campaign they’d watched unfold for over four years.

Many of them deny it now, but a lot of 2016 Trump voters were worried during the early stages of the Russia collusion investigation. True, the evidence seemed thin, and the very idea that the US and allied security apparatus would allow Trump to take office if they really thought he might be under Russian blackmail seemed a bit preposterous on its face. But to many conservatives in 2016 and early 2017, it seemed equally preposterous that the institutions they trusted, and even the ones they didn’t, would go all-in on a story if there wasn’t at least something to it. Imagine the consequences for these institutions if it turned out there was nothing to it.

We now know that the FBI and other intelligence agencies conducted covert surveillance against members of the Trump campaign based on evidence manufactured by political operatives working for the Clinton campaign, both before and after the election. We know that those involved with the investigation knew the accusations of collusion were part of a campaign “approved by Hillary Clinton… to vilify Donald Trump by stirring up a scandal claiming interference by the Russian security service.” They might have expected such behavior from the Clintons — politics is a violent game and Hillary’s got a lot of scalps on her wall. But many of the people watching this happen were Tea Party types, in spirit if not in actual fact. They give their kids a pocket Constitution for their birthday. They have Yellow Ribbon bumper stickers, and fly the POW/MIA flag under the front-porch Stars and Stripes, and curl their lip at people who talk during the National Anthem at ballgames. They’re the people who believed their institutions when they were told Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. To them, the intel community using fake evidence (including falsified documents) to spy on a presidential campaign is a big deal.

It may surprise many liberals, but most conservative normies actually know the Russia collusion case front and back. A whole ecosystem sprouted up to pore over every new development, and conservatives followed the details as avidly as any follower of liberal conspiracy theorists Seth Abramson or Marcy Wheeler. When the world learned of the infamous meeting between Trump campaign officials and Russian lawyer Natalia Veselnitskaya, it seemed like a problem and many Trump supporters took it seriously. Deep down, even those who rejected the possibility of open collusion worried that one of Trump’s inexperienced family members, or else a sketchy operative glomming onto the campaign, might have done something that, whatever its real gravity, could be successfully framed in a manner to sway a dozen of John McCain’s friends in the Senate.

Then, Trump supporters learned that Veselnitskaya was working with Fusion GPS, the political research and PR firm used by the Clinton campaign to formulate and spread the collusion accusations. They learned that the anti-Clinton information that was supposed to be the subject of the notorious meeting was provided by the same firm. They learned that she’d had dinner with Glenn Simpson, the owner of Fusion GPS, both the day before, and the day after the meeting. Needless to say, Trump supporters were skeptical of Simpson’s claim that Veselnitskaya’s meeting with Trump campaign officials never came up during either of their dinner dates, given that the content of the meeting was alleged to be the very treasonous, impeachable crime his firm was being paid to investigate and publicize.

There’s no need to relive all the details of the Russia collusion scam. The point is that conservatives were following it all very closely, in real time, and they noticed when things didn’t add up. After James Comey told Fox News’ Bret Baier that, even at the time of their interview in April 2018, he didn’t know who had funded the Steele dossier, conservatives noticed when the December 2019 DOJ Inspector General’s report showed that he had been informed of the dossier’s provenance in October 2016. And they asked themselves: Why would he lie? Lying to investigators about one’s knowledge of or involvement in a potentially criminal act is often taken as consciousness of guilt.

This was the bone that stuck in conservatives’ craw throughout the two years of hysteria over Russia. Why would Comey lie about knowing where the dossier came from? Why would the people involved claim to have seen evidence that never seemed to materialize? If the point of the Special Counsel is to take the investigation out of the hands of line investigators to avoid the appearance of political influence, why staff the office with known partisans and the same FBI personnel who originated and oversaw the case? Why was the relationship between Russian lawyer Veselnitskaya and Fusion GPS being dismissed as irrelevant? Why were people who must know better continuing to insist that the Steele dossier was originally funded by Republicans long after the claim had been debunked? Why wasn’t the media asking even these most obvious questions? And why were they giving themselves awards for refusing to ask those questions, and viciously attacking journalists who did ask them? These journalists are intelligent people — at least they present that way on television. Is it possible that these questions simply had not occurred to them? It seemed unlikely.

Many Trump supporters reasoned that it was simply not possible to carry on this campaign without some degree of coordination. That coordination perhaps did not take place in smoke-filled rooms (though they weren’t ruling it out), but at least through incentives, pressure, and vague but certain threats all well-understood by people who moved about in the same professional and social class, and who complained that they could “smell the Trump support” when they were unfortunate enough to have to patronize a Wal-Mart.

If there was a time when Trump supporters feared Robert Mueller’s goon squad, that time had passed by the 2018 midterm elections. Conservatives knew by then the whole case was bunk, and they were salivating at the prospect of watching him get chopped up by the likes of Jim Jordan and Devin Nunes. And he did.

The collusion case wasn’t only used to damage Trump in the polls or distract from his political agenda. It was used as an open threat to keep people from working in the administration. Taking a job in the Trump administration meant having one’s entire life investigated for anything that could fill CNN’s anti-Trump content requirement for another few days, whether or not it held up to scrutiny. Many administration employees quit because they were being bankrupted by legal fees due to an investigation that was known by its progenitors to be a political operation. The Department of Justice, press, and government used falsehoods to destroy lives and actively subvert an elected administration almost from the start. Perhaps worst of all, some portion of the American population was driven to the edge of madness by two years of being told that American politics had become a real-life version of The Manchurian Candidate. And not by Alex Jones, but by intelligence chiefs and politicians, amplified by media organizations which threw every ounce of their accumulated credibility behind the insanity.

For two years, Trump supporters had been called traitors and Russian bots for casting ballots for “Vladimir Putin’s c*ck holster.” They’d been subjected to a two-year gaslighting campaign by politicians, government agencies, and elite media. It took real fortitude to stand up to the unanimous mockery and scorn of these powerful institutions. But those institutions had gambled their power and credibility, and they’d lost, and now Trump supporters expected a reckoning. When no reckoning was forthcoming - when the Greenwalds, and Taibbis, and Matés of the world were not handed the New York Times’ revoked Pulitzers for correctly and courageously standing against the tsunami on the biggest political story in years - these people shed many illusions about how power really operates in their country.

Trump supporters know - I think everyone knows - that Donald Trump would have been impeached and probably indicted if Robert Mueller had proven that he’d paid a foreign spy to gather damaging information on Hillary Clinton from sources connected to Russian intelligence and disseminate that information in the press. Many of Trump’s own supporters wouldn’t have objected to his removal if that had happened. Of course that is exactly what the Clinton campaign actually did, yet there were no consequences for it. Indeed, there has been almost no criticism of it.

Trump supporters had gone from worrying the collusion might be real, to suspecting it might be fake, to seeing proof that it was all a scam. Then they watched as every institution - government agencies, the press, Congressional committees, academia - blew right past it and gaslit them for another year. To this day, something like half the country still believes that Trump was caught red-handed engaging in treason with Russia, and only escaped a public hanging because of a DOJ technicality regarding the indictment of sitting presidents. Most galling, conservatives suspect that within a few decades liberals will use their command over the culture to ensure that virtually everyone believes it. This is where people whose political identities have for decades been largely defined by a naive belief in what they learned in civics class began to see the outline of a Regime that crossed not only partisan, but all institutional boundaries. They'd been taught that America didn't have Regimes, but what else was this thing they'd seen step out from the shadows to unite against their interloper president?

THE ESTABLISHMENT UNITESGOP propaganda still has many conservatives thinking in terms of partisan binaries. Even the dreaded RINO (Republican-In-Name-Only) slur serves the purposes of the party, because it implies that the Democrats represent an irreconcilable opposition. But many Trump supporters see clearly that the Regime is not partisan. They know that the same institutions would have taken opposite sides if it had been a Tulsi Gabbard vs. Jeb Bush election. It’s hard to describe to people on the Left, who are used to thinking of American government as a conspiracy and are weaned on stories about Watergate, COINTELPRO, and Saddam’s WMD, how shocking and disillusioning this was for people who encouraged their sons and daughters to go fight for their country when George W. Bush declared war on Iraq.

They could have managed the shock if it only involved the government. But the behavior of the press is what radicalized them. Trump supporters have more contempt for journalists than they have for any politician or government official, because they feel most betrayed by them. The idea that the corporate press is driven by ratings and sensationalism has become untenable over the last several years. If that were true, there’d be a microphone in the face of every executive branch official demanding to know what the former Secretary of Labor meant when he said that Jeffrey Epstein “belonged to intelligence.” The corporate press is the propaganda arm of the Regime these people are now seeing in outline. Nothing anyone says will ever make them unsee that, period.

This is profoundly disorienting. Again, we’re not talking about pre-2016 Greenwald readers or even Ron Paul libertarians, who swallowed half a bottle of red pills long ago. These are people who attacked Edward Snowden for “betraying his country,” and who only now are beginning to see that they might have been wrong. It’s not because the parties have been reversed, and it’s not because they’re bitter over losing. They just didn’t know. If any country is going to function over the long-term, not everyone can be a revolutionary. Most people have to believe what they’re told and go with the flow most of the time. These were those people. I’m pretty conservative by temperament, but most of my political friends are on the Left. I spend a good deal of our conversations simply trying to convince them that these people are not demons, and that this political moment is pregnant with opportunity.

Many Trump supporters don’t know for certain whether ballots were faked in November 2020, but they know with apodictic certainty that the press, the FBI, and even the courts would lie to them if they were. They have every reason to believe that, and it’s probably true. They watched the corporate press behave like animals for four years. Tens of millions of people will always see Brett Kavanaugh as a gang rapist, based on an unproven accusation, because of CNN. And CNN seems proud of that. They helped lead a lynch mob against a high school kid. They cheered on the most deadly and destructive riots in decades.

Conservatives have always complained that the media had a liberal bias. Fine, whatever: they still thought the press would admit the truth if they were cornered. They don’t believe that anymore. What they’ve witnessed in recent years has shown them that the corporate press will say anything, do anything, to achieve a political objective, or simply to ruin someone they perceive as an opponent. Since my casual Twitter thread ended up in the mouths of Tucker Carlson and Donald Trump, I’ve received hundreds of messages from people saying that I should prepare to be targeted. Others don’t think that will happen, but even most of them don’t think it’s an irrational concern. We’ve seen an elderly lady receive physical threats after a CNN reporter accosted her at home to accuse her of aiding Kremlin disinformation ops. We’ve seen them threaten to dox someone for making a humorous meme.

Throughout 2020, the corporate press used its platform to excuse and encourage political violence. Time Magazine told us that during the 2020 riots, there were weekly conference calls involving - among others - leaders of the protests, local officials responsible for managing them, and members of the media charged with reporting on the events. They worked together with Silicon Valley to control the messaging about the ongoing crisis for maximum political effect. In case of a Trump victory, the same organization had protesters ready to be activated by text message in 400 cities the day after the election. Every town with a population over 50,000 would have been in for some pre-planned, centrally-controlled mayhem. In other countries we call that a color revolution.

Throughout the summer, establishment governors took advantage of COVID to change voting procedures, often over the protests of the state legislatures. It wasn’t only the mass mailing of live ballots: they also lowered signature matching standards, axed existing voter ID and notarization requirements, and more. Many people reading this might think those were necessary changes, either due to the virus or to prevent potential voter suppression. I won’t argue the point, but the fact is that the US Constitution states plainly that “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections... shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.” As far as conservatives were concerned, state governors used COVID to unconstitutionally usurp their legislatures’ authority to unilaterally alter voting procedures just months before an election in order to help Biden make up for a massive enthusiasm gap by gaming the mail-in ballot system. Lawyers can argue over the legitimacy of the procedural modifications; the point is that conservatives believe in their bones - and I think they’re probably right - that the cases would have been treated differently, in both the media and in court, if the parties were reversed.

And then came the Hunter Biden laptop scandal. Liberals dismiss the incident because, after four years of obsessing over the activities of the Trump children, they insist they’re not interested in the behavior of the candidate’s family members. But this misses the point entirely. Big Tech ran a coordinated censorship campaign against a major American newspaper while the rest of the media spread base propaganda to protect a political candidate. And once again, the campaign crossed institutional boundaries, with dozens of former intelligence officials throwing their weight behind the baseless and now-discredited claim that the laptop was part of a Russian disinformation campaign. That lie was promoted by Big Tech companies, while the true information being reported by The New York Post about the laptop’s contents was suppressed. That is what happened.

Even the tech companies themselves now admit it was a “mistake” - Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey said it was an error and apologized - but the election is over, Joe Biden has appointed Facebook’s government regulations executive as his ethics arbiter, so who cares, right? It hardly needs saying that if The New York Times had Donald Trump Jr.’s laptop, full of pictures of him smoking crack and engaging in group sex, lots of lurid family drama, and emails with pretty direct discussions of political corruption, the Paper of Record would not have had its accounts suspended for reporting on it. Let’s remember that stories of Trump being pissed on by Russian prostitutes and blackmailed by Putin were promoted as fact across the media spectrum and used as the basis for a multi-year criminal investigation, when the only evidence was a document paid for by his opposition and disavowed by its primary source.

The reaction of Trump supporters to all this was not, “no fair!” That was how they felt about Romney’s “binders of women” in 2012 or Harry Reid’s lie that Romney paid no federal taxes. This is different. Now they were beginning to see, accurately, that the institutions of their country — all of them — had been captured by people prepared to use any means to exclude them from the political process. And yet they showed up in record numbers to vote. Trump got 13 million more votes than in 2016 - 10 million more than Hillary Clinton had gotten.

As election day became election night and the tallies rolled in, Trump supporters allowed themselves some hope. But when the four critical swing states (and only those states) went dark around midnight, they knew.

Over the following weeks, they were shuffled around between honest critics, online grifters, and media scam artists selling them conspiracy theories. They latched onto one then another increasingly outlandish theory as they tried to put a concrete name on something very real, of which election day was only the culmination. Media and Big Tech did all they could to make things worse. Everything about the election was strange, confusing, and unprecedented - the changes to procedure, unprecedented mail-in voting, counting delays, etc - but rather than admit that and bring everything into the open, they banned discussion of it (even in private messages!), and launched an absurd propaganda campaign telling us that it was - I’m not making this up - the most well-run and secure election in American history.

Conservatives know - again, I think probably everyone knows - that just as Don Jr.’s laptop would have been the story of the century, if everything about the election dispute was the same, except the parties were reversed, suspicions about the outcome would have been taken very seriously. See 2016 for proof.

Even the judiciary had forfeited its credibility with these voters because of the opposition’s embrace of political violence. Trump supporters say, with good reason: What judge will stick his neck out for Trump knowing he’ll be destroyed in the media as a violent mob burns down his house? Maybe most judges would do their jobs, but given the events of the last four years it’s not an unreasonable concern, and the concern itself is enough to cast the whole system in doubt. Again, we know, thanks to Time Magazine, that riots were planned in cities across the country if Trump had won. Sure, they were “protests”, but they were planned by the same people as during the summer, and everyone knows what it would have meant. The Chamber of Commerce took the threat of a second round of destruction of its members’ property seriously enough to offer its assistance to the “well-funded cabal of powerful people, ranging across industries and ideologies, working together behind the scenes to influence perceptions, change rules and laws, steer media coverage and control the flow of information” - Time’s words, not mine.

Trump voters were adamant that the governors’ changes to election procedures were unconstitutional. Everything in law is open to interpretation, but it doesn’t require a Harvard Law degree to read Article 1, Section 4 (quoted above) and come to that conclusion. But they also knew the cases wouldn’t see a courtroom until after the election, and what judge was going to make a ruling that would be framed as a judicial coup d’etat just because some governors didn’t go through the proper channels? Even a judge willing to accept the personal risk would have also to be willing to inflict the chaos that would follow on the country. Even a well-intentioned judge could convince himself that, whatever happened or didn’t happen, as a public servant he had no right to impose an opinion guaranteed to lead to mass violence - because the threat was not implied, it was direct. Some Trump supporters, unfortunately, thought the license for political violence applied to everyone; the hundreds of them now sitting in federal jails learned the hard way that it wasn’t true.

From the perspective of Trump’s supporters, the entrenched bureaucracy and security state subverted their populist president from day one. The natural guardrails of the Fourth Estate were removed because the press was part of the operation. Election rules were changed in an unconstitutional manner that could only be challenged after the deed was done, when judges and officials would be playing chicken with a direct threat of burning cities. Political violence was legitimized and encouraged. Major newspapers and sitting presidents were banned from social media, while the opposition enjoyed free rein to promote stories that were discredited once it was too late to matter. Conservatives put these things together and concluded that, whatever happened on November 3, 2020, it was not a free and fair democratic election in any sense that would have had meaning before Donald J. Trump was a candidate.

Trump supporters were led down some rabbit holes. But they are absolutely right that the institutions and power centers of this country have been monopolized by a Regime that believes they are beneath representation, and will observe no limits to prevent them getting it. I encourage people on the Left to recognize the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity in front of them. You’re not going to agree with the conservatives on everything. But if in 2004 I had told you that the majority of the GOP voter base would soon be seeing the folly of the Iraq War, becoming skeptical of state surveillance, and beginning to see the need for action to help the poor and working classes, you’d have told me such a thing would transform the country. Take the opportunity. These people are not demons, and they are ready to listen in a way they haven’t in a long, long time.

Darryl Cooper is the host of The MartyrMade Podcast, Co-host of The Unraveling w/Jocko Willink, and author of "that" Twitter thread.

Read more:

https://outsidevoices.substack.com/p/author-of-the-mega-viral-thread-on

See also (Vladimir Putin’s c*ck holster): https://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/33508

See also:

dishonest stories...https://yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/32971

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!