Search

Recent comments

- hairy...

1 hour 17 min ago - beaudifool....

2 hours 25 min ago - escalationing....

12 hours 41 min ago - not happy, john....

17 hours 29 sec ago - corrupt....

22 hours 22 min ago - laughing....

1 day 15 min ago - meanwhile....

1 day 1 hour ago - a long day....

1 day 3 hours ago - pressure....

1 day 4 hours ago - peer pressure....

1 day 19 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

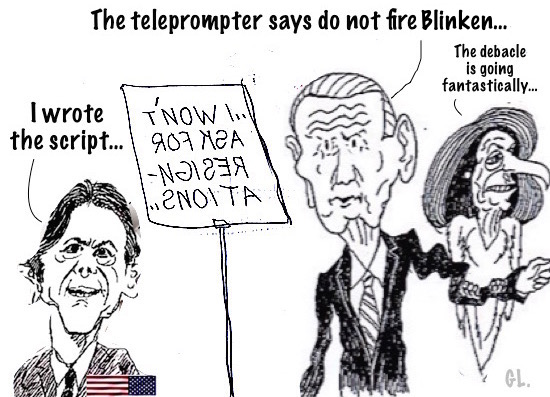

escape from the debacle...

blinken

blinken

Dozens of Australian nationals and visa holders stranded in Afghanistan were plucked from the suburbs of Kabul this week as part of a tense multinational extraction effort to get foreigners into the airport and on board evacuation flights, the ABC can reveal.

Key points:- Crowds and Taliban guards have prevented many in Afghanistan from entering Kabul's airport

- A multinational mission involving a convoy of buses collected Australian nationals and visa holders and brought them inside the terminal

- One man who boarded a bus said he did not know who was in charge of the mission, but he was "happy for his family" that they made an evacuation flight

On Tuesday, at least three buses went to various muster points around Kabul to pick up foreign nationals, including Australians, before making their way to the airport.

Similar missions to extract Australians and visa holders also operated in the following days, the ABC understands, before Australia's evacuation mission came to an end on Thursday.

The ABC has been in touch with two Australian families who took the long and tense bus journey with dozens of others.

They witnessed desperate Afghans plead for help from the side of the road, while Taliban fighters beat back other hopeful evacuees.

Like so many, those families were in deep despair after making several attempts to reach the airport for evacuation flights, only to be repeatedly repulsed by massive crowds and violent Taliban guards.

Since the Taliban swept into the Afghan capital, countries including the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, France and Germany have all conducted operations outside Kabul airport to retrieve stranded nationals.

But Australians, until this week, had to make their own way into the terminal.

The 12-hour bus ride to get to Kabul airportAfter making several appeals for help to Australian authorities, the families were told to wait at a designated pick-up point for a bus, which the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) said would be "facilitated by local authorities".

Read more:

Let's hope the friends of my friend can get out...

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW...

- By Gus Leonisky at 28 Aug 2021 - 8:39am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

bad advice for 20 years...

White House press secretary Jen Psaki rejected the idea that President Joe Biden would ask any of his top generals to resign.

The terrorist attack in Kabul Thursday killed 13 U.S. service members and dozens of Afghans, as evacuations have continued at the airport.

Psaki was asked Friday about members of the Marine Corps criticizing top generals on social media.

Al Jazeera English correspondent Kimberly Halkett asked, “Does [the president] believe he was given bad advice? And will he ask for any resignations of his generals given the high cost of American and Afghan lives?”

“No to both of those questions,” Psaki responded.

“I think that what the president looks at the events of yesterday as is a tragedy and one that was felt viscerally by the leaders of the military as well,” she continued. “Losing members of your men and women working for you from the service branches is devastating.”

“It is a reflection on all of them and the people on the ground that they are continuing to implement this mission even under difficult and risky circumstances.”

Read more:

https://www.mediaite.com/tv/psaki-says-biden-isnt-going-to-ask-for-resignations-of-top-generals-over-afghanistan/

till the next defeat...

By Dennis B. Ross

Mr. Ross is the counselor at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

This essay has been updated to reflect recent events.

The cascade of crises in Afghanistan has left many Americans wondering if our credibility on the world stage has suffered a mortal blow. Not since the fall of Saigon and the ignominious evacuation of the last Americans in 1975 has the United States been so vulnerable to fundamental questions about America’s reliability, about whether friends and allies will ever again be able to count on U.S. commitments.

Before we draw definitive conclusions, however, a little perspective is in order.

Vietnam, cited so often in recent days, was undoubtedly a debacle. But it did not spell the end of American leadership on the world stage, nor did it lead others to believe they could not depend on the United States. And since then, there have been many other geopolitical challenges and top-level decisions (or lack thereof) that have cast doubt on American credibility. They did not, however, lead to a waning of American influence.

During the Carter administration, the Iran hostage crisis — marked by a failed rescue mission — dragged on for more than a year as the rest of the world witnessed American impotence. Following the loss of 241 Marines in the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing, President Ronald Reagan vowed to make the perpetrators pay. Within a few months, however, Mr. Reagan withdrew all forces from Lebanon. The United States never retaliated for the bombing.

During the Clinton administration, terrorists bombed the Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia, killing 19 U.S. airmen. Despite tough talk and access to information that implicated Iran, the United States didn’t retaliate then, either.

President George W. Bush and the invasion of Iraq are a story unto themselves. The invasion lacked legitimate justification: There never were any weapons of mass destruction. The United States also failed to sufficiently fill the leadership vacuum following the removal of Saddam Hussein, contributing to a sectarian conflictand the subsequent creation of ISIS. President Barack Obama drew a red line on the use of chemical weapons in Syria and failed to react militarily when chemical weapons were, in fact, used against Syrian civilians.

And with President Donald Trump, the examples are almost too numerous to mention. A choice two include frequent threats to pull out of NATO and an impulsive decision to withdraw from Syria (that was partially walked back by his advisers).

Each of these examples damaged American credibility worldwide, although not necessarily to the same extent. But countries continued to ask for — and offer — support.

Despite the messy exit from Kabul and the devastating bombingsat the Kabul Airport, Afghanistan will be no different. Partners and allies will publicly decry American decisions for some time, as they continue to rely on the U.S. economy and military. The reality will remain: America is the most powerful country in the world, and its allies will need its help to combat direct threats and an array of new, growing national security dangers, including cyberwar and climate change.

That does not mean that the United States can dismiss the costs of its mistakes in Afghanistan. But it does show that America can recover.

President Biden declared: “America is back.” Going forward, it will be important to show that the United States is not walking away from its responsibilities, that it will not brook challenges. Instead, America needs to reaffirm its commitments.

To begin, the administration must start by completing the evacuation of Afghanistan. It’s important to succeed not only in evacuating all Americans but also in evacuating those Afghans who worked with us and are now at risk. We are morally obligatedto them.

As of now, President Biden plans to stick to the Aug. 31 withdrawal deadline, saying that each day of operations in Afghanistan “brings added risk to our troops.” The deaths of American Marines on Thursday prove he is right.

Still, the administration should consider extending the Aug. 31 deadline, despite the very real risks of staying longer. America’s duty is to oversee a safe withdrawal. An artificial deadline should not take precedence over that or hurry us into mistakes. The United States has the means to pressure the Taliban to accept a limited extension and to permit and safeguard continuing evacuations even after American forces leave. The United States can continue to politically isolate the Taliban and keep frozen the billions of dollars in Afghan assets that the Taliban want and need. Mr. Biden can make clear that the United States will get out but that it needs more time. It is in the Taliban’s interest to facilitate the U.S. exit.

Second, the administration must discuss a long-term plan for the greater Middle East with European allies and other regional stakeholders. This is not the time to shift forces out of the area, including those in Iraq and Syria. The United States cannot allow ISIS or other armed organizations to regroup. Instead, the United States must clearly explain American aims in the Middle East, what America will be prepared to do to fulfill them and the roles it needs its allies to play.

Third, the administration must respond to enemy attacks or challenges to international norms with strength and conviction. Its message to the world must be clear: U.S. forces and allies cannot be attacked with impunity. Mr. Biden’s retaliatory unmanned airstrike against an ISIS-K planner Friday to avenge the airport bombings was a good first step. More actions against those who attack or threaten the U.S. and its partners will be needed to drive home the point.

It’s easy to despair over the idea that the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan has forever doomed American credibility. Undeniably, the United States has paid and will likely continue to pay a high price in Afghanistan.

But it can recoup, just as it has before.

Dennis Ross is the counselor at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. He served in numerous senior national security positions in the Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Clinton and Obama administrations.

Read more:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/29/opinion/afghanistan-withdrawal-history.html

Read from top.

The US cannot recover a soupçon of dignity while Julian Assange is in prison.

not as debacled as it looks...

Antony Blinken on Afghanistan by Antony BlinkenGood afternoon. I’d like to give you all an update on the situation in Afghanistan and our ongoing efforts there, particularly as they relate to U.S. citizens, and then I’m very happy to take your questions.

Let me begin with my profound appreciation for our diplomats and service members who are working around the clock at the airport in Kabul and at a growing number of transit sites to facilitate the evacuation of Americans, their families, citizens of allied and partner nations, Afghans who have partnered with us over the last 20 years, and other Afghans at risk. They are undertaking this mission under extremely difficult circumstances, with incredible courage, skill, and humanity.

Since August 14th, more than 82,300 people have been safely flown out of Kabul. In the 24-hour period from Tuesday to Wednesday, approximately 19,000 people were evacuated on 90 U.S. military and coalition flights. Only the United States could organize and execute a mission of this scale and this complexity.

As the President has made clear, our first priority is the evacuation of American citizens. Since August 14th, we have evacuated at least 4,500 U.S. citizens and likely more. More than 500 of those Americans were evacuated in just the last day alone.

Now, many of you have asked how many U.S. citizens remain in Afghanistan who want to leave the country. Based on our analysis, starting on August 14 when our evacuation operations began, there was then a population of as many as 6,000 American citizens in Afghanistan who wanted to leave. Over the last 10 days, roughly 4,500 of these Americans have been safely evacuated along with immediate family members. Over the past 24 hours, we’ve been in direct contact with approximately 500 additional Americans and provided specific instructions on how to get to the airport safely. We will update you regularly on our progress in getting these 500 American citizens out of Afghanistan.

For the remaining roughly 1,000 contacts that we had who may be Americans seeking to leave Afghanistan, we are aggressively reaching out to them multiple times a day through multiple channels of communication – phone, email, text messaging – to determine whether they still want to leave and to get the most up-to-date information and instructions to them for how to do so. Some may no longer be in the country. Some may have claimed to be Americans but turn out not to be. Some may choose to stay. We’ll continue to try to identify the status and plans of these people in the coming days.

Thus, from this list of approximately 1,000, we believe the number of Americans actively seeking assistance to leave Afghanistan is lower, likely significantly lower.

Having said that, these are dynamic calculations that we are working hour by hour to refine for accuracy. And let me, if I can, just take a moment to explain why the numbers are difficult to pin down with absolute precision at any given moment. And let me start with Americans who are in Afghanistan and we believe want to leave.

First, as I think all of you know, the U.S. Government does not track Americans’ movements when they travel around the world. When Americans visit a foreign country or if they reside there, we encourage them to enroll with the U.S. embassy. Whether they do or not is up to them; it’s voluntary. And then, when Americans leave a foreign country, it’s also up to them to de-enroll. Again, that’s a choice, not a requirement.

Particularly given the security situation in Afghanistan, for many years we have urged Americans not to travel there. We’ve repeatedly asked Americans who are in Afghanistan to enroll. And since March of this year, we’ve sent 19 separate messages to Americans enrolled with the embassy in Kabul, encouraging and then urging them to leave the country. We’ve amplified those direct messages on the State Department website and on social media. We even made clear that we would help pay for their repatriation, and we’ve provided multiple communication channels for Americans to contact us if they’re in Afghanistan and want help in leaving.

The specific estimated number of Americans in Afghanistan who want to leave can go up as people respond to our outreach for the first time, and it can go down when we reach Americans we thought were in Afghanistan who tell us they’ve already left. There could be other Americans in Afghanistan who never enrolled with the embassy, who ignored public evacuation notices, and have not yet identified themselves to us.

We’ve also found that many people who contact us and identify themselves as American citizens, including by filling out and submitting repatriation assistance forms, are not, in fact, U.S. citizens – something that can take some time to verify. Some Americans may choose to stay in Afghanistan – some who are enrolled, and some who are not. Many of them are dual nationals who may consider Afghanistan their home, who’ve lived there for decades, or who want to stay close to extended family. And there are Americans who are still evaluating their decision to leave based on the situation on the ground that evolves daily – in fact, that evolves hourly.

Some are understandably very scared. Each has a set of personal priorities and considerations that they alone can weigh. They may even change their mind from one day to the next, as has happened and will likely continue to happen.

Finally, over the past 10 days we’ve been moving hundreds of American citizens out of Afghanistan every day, in most cases guided to the airport by us, in some cases getting there on their own, in other cases with the help of third countries or private initiatives. We cross-check our list against flight manifests, against arrival records, against other databases. There’s usually a lag of about 24 hours for us to verify their status. So when you take into account all of these inputs that we use to arrive at our assessment of the number of Americans still in Afghanistan and who want to leave, you start to understand why this is a hard number to pin down at any given moment and why we’re constantly refining it.

And that’s also why we continue to be relentless in our outreach. Since August 14th, we’ve reached out directly to every American enrolled with us in Afghanistan, often multiple times. Hundreds of consular officers, locally employed staff, here in Washington, at dozens of embassies and consulates around the world, are part of what has been an unprecedented operation. They’re phone banking, text banking, writing and responding to emails, working around the clock to communicate individually with Americans on the ground.

Since August 14th, we’ve sent more than 20,000 emails to enrolled individuals, initiated more than 45,000 phone calls, and used other means of communication, cycling through and updating our list repeatedly. We’re also integrating information in real time that’s provided to us by members of Congress, by nongovernmental organizations, and U.S. citizens about Americans who may be in Afghanistan and want to get out.

These contacts are how we determine the whereabouts of Americans who may be in Afghanistan, whether they want to leave, whether they need help, and then to give them specific, tailored instructions on how to leave with real-time emergency contact numbers to use should they need it.

Now, let me turn to the number of Americans who have been evacuated. As I said, we believe we’ve evacuated more than 4,500 U.S. passport holders as well as their families. That number is also a dynamic one. That’s because in this critical stretch, we’re focused on getting Americans and their families onto planes, out of Afghanistan as quickly as possible and then processing the total numbers when they’re safely out of the country. We also verify our numbers to make sure that we aren’t inadvertently undercounting or double counting.

So I wanted to lay all that out because I know it is a fundamental question that so many of you have had, and it really merits going through the information, the explanation so you see how we arrive at it.

While evacuating Americans is our top priority, we’re also committed to getting out as many Afghans at risk as we can before the 31st. That starts with our locally employed staff, the folks who’ve been working side by side in our embassy with our diplomatic team. And it includes Special Immigrant Visa program participants and also other Afghans at risk. It’s hard to overstate the complexity and the danger of this effort. We’re operating in a hostile environment in a city and country now controlled by the Taliban, with the very real possibility of an ISIS-K attack. We’re taking every precaution, but this is very high-risk.

As the President said yesterday, we’re on track to complete our mission by August 31st provided the Taliban continue to cooperate and there are no disruptions to this effort. The President has also asked for contingency plans in case he determines that we must remain in the country past that date. But let me be crystal-clear about this: There is no deadline on our work to help any remaining American citizens who decide they want to leave to do so, along with the many Afghans who have stood by us over these many years and want to leave and have been unable to do so. That effort will continue every day past August 31st.

The Taliban have made public and private commitments to provide and permit safe passage for Americans, for third-country nationals, and Afghans at risk going forward past August 31st. The United States, our allies and partners, and more than half of the world’s countries – 114 in all – issued a statement making it clear to the Taliban that they have a responsibility to hold to that commitment and provide safe passage for anyone who wishes to leave the country – not just for the duration of our evacuation and relocation mission, but for every day thereafter.

And we’re developing detailed plans for how we can continue to provide consular support and facilitate departures for whose who wish to leave after August 31st. Our expectation – the expectation of the international community – is that people who want to leave Afghanistan after the U.S. military departs should be able to do so. Together we will do everything we can to see that that expectation is met.

Let me just close with a note on the diplomatic front. In all, more than two dozen countries on four continents are contributing to the effort to transit, temporarily house, or resettle those who we are evacuating. That didn’t just happen. It’s the product of an intense diplomatic effort to secure, detail, and implement transit agreements and resettlement commitments. We are deeply grateful to those countries for their generous assistance.

This is one of the largest airlifts in history, a massive military, diplomatic, security, and humanitarian undertaking. It’s a testament both to U.S. leadership and to the strength of our alliances and partnerships. We’ll be relying and building upon that strength moving forward as we work with our allies and partners to forge a unified diplomatic approach to Afghanistan. That was a point the President underscored in yesterday’s G7 leaders’ meeting on Afghanistan and it’s one that I and other senior members of the State Department have made in our constant communication with allies and partners in recent days to ensure that we’re aligned and united as we move forward – not only when it comes to the immediate mission, but also on what happens after August 31st on counterterrorism, on humanitarian assistance, on our expectations of a future Afghan government. That intense diplomatic work is ongoing as we speak and it will continue in the days and weeks ahead.

So I talked a lot about numbers this afternoon, but even as we’re laser-focused on the mission, we know that this is about real people, many scared, many desperate. I’ve seen the images, I’ve read the stories, I’ve heard the voices, so much of that reported by you and your colleagues so courageously. Like many of you, I read the report of the Afghan translator whose two-year-old daughter was trampled to death on Saturday while waiting outside the airport. I’ve got two small kids of my own. Reading that story and others was like getting punched in the gut.

All of us at the State Department and across the U.S. Government feel that way. We know that lives and futures, starting with our fellow citizens – including the lives of children – hang in the balance during these critical days. And that’s why everyone on our team is putting everything they have into this effort. Thanks very much, and happy to take questions.

MR PRICE: Matt.

QUESTION: Thanks. Thanks, Mr. Secretary, for coming down and doing this. On your – two things really briefly. I’ll try to be as brief as possible. Two things. On your numbers of the American citizens, does that include green card holders, LPRs? And if it doesn’t or does —

SECRETARY BLINKEN: No, it does not. Let me clear, it does not.

QUESTION: Oh, it does not. Okay. Is there a way to get the number?

SECRETARY BLINKEN: These are blue passport holders.

QUESTION: Okay. But have LPRs also been contacted?

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Yep.

QUESTION: And what about SIV applicants, people who are eligible?

SECRETARY BLINKEN: We are in contact with —

QUESTION: So we can get numbers for those even if you don’t —

SECRETARY BLINKEN: — all of the different —

QUESTION: And then —

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Go ahead. I’m sorry, Matt.

QUESTION: It’s okay. I don’t expect you to have all of the numbers. But then since this whole thing began there’s been a lot of criticism of the administration over how it handled it, and there’s been a lot of pushback from people within the administration about the hand that you were basically dealt or what you say you were dealt by the previous administration in terms of the deal with the Taliban, in terms of the SIV program, in terms of the broader refugee program. But you guys have been in office for almost eight months. It’s been five months since the President’s decision was made. Is there anything about the shortcomings that have been so readily identified by all sorts of people that you guys are actually willing to take responsibility for yourselves?

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Thanks, Matt. Let me say two things. First, with regard to the numbers and these different categories, as you’ve seen by how I’ve laid out how we get to the numbers of Americans, this is both incredibly complicated and incredibly fluid. Any number I give you right now is likely to be out of date by the time we leave this briefing room. So what we’re doing is very carefully tabulating everything we have, cross-checking it, referencing it, using different databases. We will have numbers for all those different categories in the days ahead and after this initial phase of efforts to bring people out of Afghanistan ends.

And with regard to the second part of your question, about taking responsibility: I take responsibility, I know the President has said he takes responsibility, and I know all of my colleagues across government feel the same way. And I can tell you that there will be plenty of time to look back at the last six or seven months, to look back at the last 20 years, and to look to see what we might have done differently, what we might have done sooner, what we might have done more effectively. But I have to tell you that right now, my entire focus is on the mission at hand. And there’s going to be, as I said, plenty of time to do an accounting of this when we get through that mission.

MR PRICE: Lara.

QUESTION: Thank you, Mr. Secretary. Could you speak today about the future of the U.S. Embassy in Kabul, whether it will remain or American diplomats will remain in Kabul after the military withdrawal on the 31st? And also more broadly, we’re already seeing women being repressed in Afghanistan by the Taliban, people being attacked, intimidated, being kept from getting to the airport. I’m wondering if you can give us any concrete examples of steps that the United States is going to take to assure SIV applicants and other high-value – or I’m sorry, high-target, high-risk Afghans, that they’re not going to be forgotten when the United States military leaves.

SECRETARY BLINKEN: With regard to our diplomatic engagement, we’re looking at a series of options, and I’m sure we’ll have more on that in the coming days and weeks, but we’re looking at a variety of options. And as I said earlier, particularly because the effort to bring out of Afghanistan those who want to leave does not end with the military evacuation plan on the 31st, we are very focused on what we need to do to facilitate the further departure of people who wish to leave Afghanistan, and that is primarily going to be a diplomatic effort, a consular effort, an international effort because other countries feel exactly the same way.

And I’m sorry, the second part of your question?

QUESTION: Just if there are any concrete steps —

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Oh, yes, I’m sorry.

QUESTION: — that you can give to people who are very worried right now, understandably, about whether they’re just going to be forgotten, left behind, disappeared once the United States withdraws its military and can no longer protect their safe passage to the airport or their other livelihoods.

SECRETARY BLINKEN: The short answer is no, they will not be forgotten. And as I said, we will use every diplomatic, economic assistance tool at our disposal working hand-in-hand with the international community, first and foremost to ensure that those who want to leave Afghanistan after the 31st are able to do so, as well as to deal with other issues that we need to be focused on, including counterterrorism and humanitarian assistance, and expectations of a future Afghan government.

I mentioned a few moments ago that we got 114 countries around the world to make clear to the Taliban the international expectation that people will continue to be able to leave the country after the military evacuation effort ends. And we certainly have points of incentive and points of leverage with a future Afghan government to help make sure that that happens. But I can tell you again – from my perspective, from the President’s perspective – this effort does not end on August 31st. It will continue for as long as it takes to help get people out of Afghanistan who wish to leave.

QUESTION: What’s your level of confidence today that the Taliban will actually abide by some of these requirements and expectations that the international community has put on it?

SECRETARY BLINKEN: I’m not going to put a percentage on it. I can just tell you again that the Taliban has made their own commitments. They’ve made them publicly. They’ve made them privately. And again, I think they have a very strong self-interest in acting with a modicum of responsibility going forward. But they will make their own determinations.

MR PRICE: Andrea.

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Andrea.

QUESTION: Mr. Secretary, thank you. But the Taliban right now, focusing on the mission right now, are not living up to their commitments. People are being stopped trying to get into the airport. I’m talking about women, SIVs, others – Afghans, people with papers – and they’re being stopped outside the airport now. There are total bottlenecks which seem to rise to the level of what the President said were the contingency – contingencies if the Taliban is not complying, if the flow can’t continue. We’re loading planes, but some planes are leaving without – and some people are people who have private planes waiting for them with landing rights but can’t get into the airport. As well as beyond the SIVs there are lawyers, there are judges, women lawyers, judges, educators – we’ve told them for 20 years you can live up to your potential, and now they feel abandoned.

And then finally, I’d like to ask you about the local hires. We evacuated our embassy, and there have been cables back that I know you must be familiar with or your teams are of people who feel completely betrayed. And these are thousands of people that we rely on in embassies all – embassies around the world. The message is going forward that we will not be loyal. They were not told about the evacuation. They were not put on those choppers with our American staff. And they were forced – many of them – to find their own way through the Taliban checkpoints and then get turned away at the airport, and some even got turned away once they were inside.

So what is the message to people working for the U.S. Government? Veterans’ groups are angry about the SIVs, and then there are all the millions of Afghan women who have told their daughters and been raised under this promise of a future which the Taliban are already, according to Ambassador Verveer today, is – are denying. There are horrifying examples from provinces and from inside Kabul of people being targeted door to door, people in safe houses being sought out. And all this promise of you will be safe – the Taliban spokesman said stay in your homes because we haven’t told all of our people how to treat women, how to respect women. They also say you can go to school, you can work, as long as you comply with Sharia law, which, under their interpretation, is the most extreme example of the Islamic code that is seen anywhere in the world.

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Andrea, a few things. First, of the 82,000-plus people who so far have been evacuated, about 45, 46 percent have been women and children, and we’ve been intensely focused particularly on making sure that we can get women at risk out of harm’s way.

Second, with regard to women and other Afghans at risk going forward, we will use, I will use, every diplomatic, economic, political, and assistance tool at my disposal, working closely with allies and partners who feel very much the same way, to do everything possible to uphold their basic rights. And that’s going to be a relentless focus of our actions going forward.

Locally employed staff – along with American citizens, nothing is more important to me as Secretary of State than to do right by the people who have been working side-by-side with American diplomats in our embassy. And I can tell you, Andrea, that we are relentlessly focused on getting the locally employed staff out of Afghanistan and out of harm’s way. And let me leave it at that for now.

MR PRICE: Rosiland.

QUESTION: Mr. Secretary, thank you. I wanted to ask a more fundamental question about the Taliban. Your spokesperson indicated in recent days that de facto the Taliban are in charge in Kabul, but there is no legal recognized government by the United States at this moment. And it kind of begs the question: Why does the United States even have to pay attention to what the Taliban wants? It’s an SDGT; it’s sanctioned by many organizations. It’s already losing access to Afghan government resources because of its past and current behavior. Why should the United States even care what the Taliban wants to be done at the airport or, frankly, anywhere else in the country since they are not, in the U.S.’s eyes, a legally recognized government? Thank you.

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Thank you. Thank you. Our focus right now is on getting our citizens and getting other – our partners – Afghan partners, third-country partners who have been working in Afghanistan with us – out of the country and to safety. And for that purpose, first, the Taliban, whether we like it or not, is in control – largely in control of the country, certainly in control of the city of Kabul. And it’s been important to work with them to try to facilitate and ensure the departure of all those who want to leave, and that has actually been something that we’ve been focused on for – from the beginning of this operation, because as a practical matter it advances our interests.

Second, we’ve been engaged with the Taliban for some time diplomatically going back years in efforts, as you know, to try to advance a peaceful settlement of the conflict in Afghanistan. There’s still talks and conversations underway even now between the Taliban and former members of the Afghan government with regard, for example, to a transfer of power and some inclusivity in a future government. And I think it’s in our interest where possible to support those efforts.

Going forward, we will judge our engagement with any Taliban-led government in Afghanistan based on one simple proposition: our interests, and does it help us advance them or not. If engagement with the government can advance the enduring interests we will have in counterterrorism, the enduring interest we’ll have in trying to help the Afghan people who need humanitarian assistance, in the enduring interest we have in seeing that the rights of all Afghans, especially women and girls, are upheld, then we’ll do it.

But fundamentally, the nature of that engagement and the nature of any relationship depends entirely on the actions and conduct of the Taliban. If a future government upholds the basic rights of the Afghan people, if it makes good on its commitments to ensure that Afghanistan cannot be used as a launching pad for terrorist attacks directed against us and our allies and partners, and in the first instance, if it makes good on its commitments to allow people who want to leave Afghanistan to leave, that’s a government we can work with. If it doesn’t, we will make sure that we use every appropriate tool at our disposal to isolate that government, and as I said before, Afghanistan will be a pariah.

MR PRICE: Francesco.

QUESTION: Thank you, Mr. Secretary. What will happen on September 1st? Will the U.S. keep any diplomatic and/or any other kind of presence in Kabul at all, and who will run the airport? Is there any progress in the discussions with the Turks – who announced their withdrawal, their military withdrawal – with the Qataris, and with the Taliban on the airport?

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Thanks. There are very active efforts on the way – underway on the part of regional countries to see whether they can play a role in keeping the airport open once our military mission leaves or, as necessary, reopening it if it closes for some period of time. And that’s happening very actively right now. The Taliban have made clear that they have a strong interest in having a functioning airport. We and the rest of the international community certainly have a strong interest in that, primarily for the purpose of making sure that anyone who wants to leave can leave past the 31st using an airport. And so that’s a very active effort that’s underway as we speak. And again, with regard to our own potential presence going forward after the 31st, we’re looking at a number of options.

MR PRICE: Thank you very much, Mr. Secretary.

SECRETARY BLINKEN: Thank you all very much.

Antony Blinken

Read more:https://www.voltairenet.org/article213868.html Read from top.diminishing returns...

This Sept. 11, a diminished president will preside over a diminished nation.

We are a country that could not keep a demagogue from the White House; could not stop an insurrectionist mob from storming the Capitol; could not win (or at least avoid losing) a war against a morally and technologically retrograde enemy; cannot conquer a disease for which there are safe and effective vaccines; and cannot bring itself to trust the government, the news media, the scientific establishment, the police or any other institution meant to operate for the common good.

A civilization “is born stoic and dies epicurean,” wrote historian Will Durant about the Babylonians. Our civilization was born optimistic and enlightened, at least by the standards of the day. Now it feels as if it’s fading into paranoid senility.

Joe Biden was supposed to be the man of the hour: a calming presence exuding decency, moderation and trust. As a candidate, he sold himself as a transitional president, a fatherly figure in the mold of George H.W. Bush who would restore dignity and prudence to the Oval Office after the mendacity and chaos that came before. It’s why I voted for him, as did so many others who once tipped red.

Instead, Biden has become the emblem of the hour: headstrong but shaky, ambitious but inept. He seems to be the last person in America to realize that, whatever the theoretical merits of the decision to withdraw our remaining troops from Afghanistan, the military and intelligence assumptions on which it was built were deeply flawed, the manner in which it was executed was a national humiliation and a moral betrayal, and the timing was catastrophic.

We find ourselves commemorating the first great jihadist victory over America, in 2001, right after delivering the second great jihadist victory over America, in 2021. The 9/11 memorial at the World Trade Center — water cascading into one void, and then trickling, out of sight, into another — has never felt more fitting.

Now Biden proposes to follow this up with his $3.5 trillion budget reconciliation bill, which The Times’s Jonathan Weisman describesas “the most significant expansion of the nation’s safety net since the war on poverty in the 1960s.”

When Lyndon Johnson launched his war on poverty, its associated legislation — from food stamps to Medicare — passed with bipartisan majorities in a lopsidedly Democratic Congress. Biden has similar ambitions without the same political means. This is not going to turn out well.

Last week, Joe Manchin, Democrat from West Virginia, published an essay in The Wall Street Journal in which he said, “I, for one, won’t support a $3.5 trillion bill, or anywhere near that level of additional spending, without greater clarity about why Congress chooses to ignore the serious effects inflation and debt have on existing government programs.”

Is the White House paying any more attention to Manchin’s message than it did to classified intelligence briefs over the summer warning of the prospect of a swift Taliban victory?

Maybe Biden supposes that the legislation, if passed, will prove increasingly popular over time, like Obamacare. That’s the optimistic scenario. Alternatively, he could suffer a legislative calamity like Hillary Clinton’s health care reform in 1994, which would have ended Bill Clinton’s presidency save for his sharp swing to the center, including ending “welfare as we know it” two years later.

Even the optimistic precedent was followed by a Democratic rout in 2010, when the party lost 63 House seats. If history repeats itself at the 2022 midterms, I doubt that even Joe Biden’s closest aides think he has the stamina to fight his way back in 2024. Has Kamala Harris shown the political talent to pick up the pieces?

Perhaps what will save the Democrats is that Biden’s weakness will tempt Donald Trump to seek (and almost certainly gain) the Republican nomination. But then there’s the chance he’d win the election.

There’s a way back from this cliff’s edge. It begins with Biden finding a way to acknowledge publicly the gravity of his administration’s blunders. The most shameful aspect of the Afghanistan withdrawal was the incompetence of the State Department when it came to expediting visas for thousands of people eligible to come to the United States. Accountability could start with Antony Blinken’s resignation.

The president might also seize the “strategic pause” Manchin has proposed and push House Democrats to pass the $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill without holding it hostage to the $3.5 trillion reconciliation bill. Infrastructure is far more popular with middle-of-the-road voters than the Great Society reprise that was never supposed to be a part of the Biden brand.

My sense is that Biden will do neither. The last few months have told us something worrying about this president: He’s proud, inflexible, and thinks he’s much smarter than he really is. That’s bad news for the administration. It’s worse news for a country that desperately needs to avoid another failed presidency.

Read more:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/07/opinion/biden-failed-afghanistan.html

See toon at top.