Search

Recent comments

- beaudifool....

23 min 43 sec ago - escalationing....

10 hours 39 min ago - not happy, john....

14 hours 59 min ago - corrupt....

20 hours 20 min ago - laughing....

22 hours 14 min ago - meanwhile....

23 hours 43 min ago - a long day....

1 day 1 hour ago - pressure....

1 day 2 hours ago - peer pressure....

1 day 17 hours ago - strike back....

1 day 17 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the industry of anzac days — no disrespect to the fallen but...

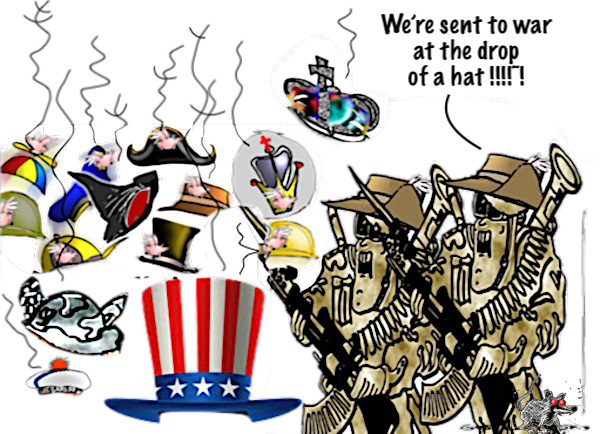

According to the fantasy, there is a ‘moral obligation’ toward dead Anzacs – but not to democratise the decisions that would throw live Anzacs into war.

There is no doubting the sincerity of the grief felt by the bereaved, those who will gather at the myriad sites of memory and mourning across Australia on Anzac Day. Let us acknowledge that sincerity at the outset, and pause respectfully.

But there is a fantasy that haunts our cult of the fallen. The fantasy is this: that our political leaders so love the serving men and women that they would never recklessly commit them to war.

Let us consider the high-profile official ceremonies. They come with lashings of vice-regal pomp, gilded functionaries, and perfect parades. Often clergymen are on hand, like God’s ushers, to mix military and religious ritual. Ancient hymns are sung, suggesting that those who enlisted are those ‘who had heard God’s message from afar’.

At such ceremonies, the leaders of the political class are often very prominent. In solemn addresses, they exalt the example of the Anzacs’ sacrifice, service, and comradeship. The rest of the year, in ordinary parliamentary speechifying and media commentary, they compete in offering tokens of their devotion to the dead, committing fantastic sums to promote the cult of the fallen, and denouncing any history that dares to veer away from a simple ‘take a bow, Australia’ spirit.

Consider the lavishness of the spending on remembrance. The latest example of extravagance is the $498 million to be spent converting the dignified Australian War Memorial into a giant museum of combat experience, filled with contemporary military hardware under vast canopies of glass.

Supposedly, big money is required to boost respect. For example, much is spent identifying and reburying the remains of the thousands of Australians who were lost or identifiable in the chaos of war. Our political leaders describe this as a ‘moral obligation’ owed by those who send our troops away. Every Anzac is sacred. Whether surviving veterans today share in this largesse is a hot issue.

Consider commercial ‘Anzac’ products. Some are bizarre parodies of respect. For instance, a famous photograph of the 11th Battalion on the Cheops Pyramid in 1915 just before their catastrophic deployment to Gallipoli has been turned into a poster for a trophy room. It is endorsed with the words ‘Fall an Anzac – Rise a Legend’. The message is clear: every lost Anzac is truly immortal.

What is all this meant to prove? Presumably, that in the eyes of our nation and its leaders, every serving soldier, sailor and aviator, past and present, is cherished. Supposedly, the political class, the ultimate decision makers upon war and peace, so love our men and women in uniform that they count every hair on every head, then and now.

Let’s explore the fantasy. Supposedly, so cherished are our warriors, that those in the corridors of power would never choose war for reasons of low political calculation. They would never be wasteful in prolonging conflicts that might be ended by diplomatic means. They would never choose war rashly, but only when it is incontrovertibly in the nation’s direct interest, and only when the very last resources of diplomacy had been exhausted.

Supposedly, so deep is the love of our Anzacs that those who sit in the cabinet rooms would never be dishonest in describing the need for deployment, and never mislead the families of those sent to fight. They would never lose strategic control over our forces, never embark upon war for sordid purposes, and never see our war aims escalated to serve the interests of others.

In short, the decision makers – generally the older generation, with their families, careers, and wealth all secure – would never imperil the lives of the generally much younger and working-class men and women by wantonly launching them into war. Would they? If they did, surely the ghosts of the dead would haunt them, and our war-making leaders, traumatised by the responsibility, would abandon their careers and slink away into obscurity. Wouldn’t they?

Is any element of this elaborate fantasy true? Let us skim across just three intensely controversial deployments.

In August 1914, with a federal election imminent, the outgoing Liberal government of Joseph Cook offered Britain an expeditionary force of 20,000 men under British command, for any objective, at any cost. The Labor government of Andrew Fisher elected in September, and later the National government led by the Labor renegade Hughes, did no better. Australia exerted no pressure on London to restrain its own expansionist war aims or those of the Entente coalition. Australia never advised London that opportunities for a negotiated end to the catastrophe should be explored. War to the bitter end was insisted upon; critics were stamped upon. The result: protracted disaster.

Flash forward fifty years. In April 1965, just before Anzac Day, the US Special Ambassador Cabot Lodge visited Australia to brief the Menzies government on the situation in Vietnam. Just ten days later, on 29 April 1965, prime minister Menzies told a late-night session of parliament – there was no vote – that Australian forces were being sent to Vietnam. He falsely suggested that this followed from a South Vietnamese request for assistance, when in fact that request had been solicited through back-channels. Only a month later the government amended the Defence Act to enable the deployment of conscripted young men anywhere beyond Australia. The result: protracted disaster.

In March 2003, the Howard government authorised the already ‘pre-deployed’ Australian forces to join combat operations to disarm Iraq of its ‘weapons of mass destruction’. Later, prime minister Howard pleaded that he had not knowingly misled the Australian people at that time because he had truly believed the faulty intelligence. But in April 2013, on the tenth anniversary of the Iraq war, he revealed in a speech that, in any case, he had always believed that Australia had to fight as an ally of the USA, because the circumstances ‘necessitated a 100 per cent ally, not a 70 or 80 per cent one’. The result: protracted disaster.

Apparently, this historical record of duplicity, deceit, and recklessness scarcely troubles the political class. For example, in November last year, the two major political parties combined in a Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Committee Inquiry to deflect the latest attempt to reform the ‘war powers’. The power to choose war remains, by a quirk of history, under the ‘royal prerogative’, reserved absolutely to the executive. Our political leaders’ cherishing of each and every Anzac is revealed as pure fantasy.

So, according to the fantasy, there is a ‘moral obligation’ toward dead Anzacs – but not to democratise the decisions that would throw live Anzacs into war. That is the true measure of our political leaders’ love and respect for those in uniform...

READ MORE:

https://johnmenadue.com/the-fantasy-that-haunts-our-cult-of-the-fallen/

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW. HE'S WORTH A MILLION SOLDIERS FOR PEACE....

- By Gus Leonisky at 25 Apr 2022 - 9:22am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

time to revisit WW1….

As we now know, the motorcade was a death trap. Six assassins lined the royal couple’s route that morning, armed with bombs and pistols. The first two failed to act, but the third, Nedeljko Čabrinović, panicked and threw his bomb onto the folded back cover of the Archduke’s convertible. It bounced off onto the street, exploding under the next car in the convoy. Franz Ferdinand and his wife, unscathed, were rushed on to the Town Hall, passing the other assassins along the route too quickly for them to act.

Having narrowly escaped death, the Archduke called off the rest of his scheduled itinerary to visit the wounded from the bombing at the hospital. By a remarkable twist of fate, the driver took the couple down the wrong route, and, when ordered to reverse, stopped the car directly in front of the delicatessen where would-be assassin Gavrilo Princip had gone after having failing in his mission along the motorcade. There, one and a half metres in front of Princip, were the Archduke and his wife. He took two shots, killing both of them.

Yes, even the official history books—the books written and published by the “winners”—record that the First World War started as the result of a conspiracy. After all, it was—as all freshman history students are taught—the conspiracy to assassinate the Archduke Franz Ferdinand that led to the outbreak of war.

That story, the official story of the origins of World War I, is familiar enough by now: In 1914, Europe was an interlocking clockwork of alliances and military mobilization plans that, once set in motion, ticked inevitably toward all out warfare. The assassination of the Archduke was merely the excuse to set that clockwork in motion, and the resulting “July crisis” of diplomatic and military escalations led with perfect predictability to continental and, eventually, global war. In this carefully sanitized version of history, World War I starts in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914.

But this official history leaves out so much of the real story about the build up to war that it amounts to a lie. But it does get one thing right: The First World War was the result of a conspiracy.

To understand this conspiracy we must turn not to Sarajevo and the conclave of Serbian nationalists plotting their assassination in the summer of 1914, but to a chilly drawing room in London in the winter of 1891. There, three of the most important men of the age—men whose names are but dimly remembered today—are taking the first concrete steps toward forming a secret society that they have been discussing amongst themselves for years. The group that springs from this meeting will go on to leverage the wealth and power of its members to shape the course of history and, 23 years later, will drive the world into the first truly global war.

Their plan reads like outlandish historical fiction. They will form a secret organization dedicated to the “extension of British rule throughout the world” and “the ultimate recovery of the United States of America as an integral part of a British Empire.” The group is to be structured along the lines of a religious brotherhood (the Jesuit order is repeatedly invoked as a model) divided into two circles: an inner circle, called “The Society of the Elect,” who are to direct the activity of the larger, outer circle, dubbed “The Association of Helpers” who are not to know of the inner circle’s existence.

“British rule” and “inner circles” and “secret societies.” If presented with this plan today, many would say it was the work of an imaginative comic book writer. But the three men who gathered in London that winter afternoon in 1891 were no mere comic book writers; they were among the wealthiest and most influential men in British society, and they had access to the resources and the contacts to make that dream into a reality.

Present at the meeting that day: William T. Stead, famed newspaper editor whose Pall Mall Gazette broke ground as a pioneer of tabloid journalism and whose Review of Reviews was enormously influential throughout the English-speaking world; Reginald Brett, later known as Lord Esher, an historian and politician who became friend, confidant and advisor to Queen Victoria, King Edward VII, and King George V, and who was known as one of the primary powers-behind-the-throne of his era; and Cecil Rhodes, the enormously wealthy diamond magnate whose exploits in South Africa and ambition to transform the African continent would earn him the nickname of “Colossus” by the satirists of the day.

But Rhodes’ ambition was no laughing matter. If anyone in the world had the power and ability to form such a group at the time, it was Cecil Rhodes.

READ MORE:

https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/35884

READ FROM TOP.

SEE ALSO:

the west's modern crusades, or what is yours is mine.....FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW >>>>>>>>>>>