Search

Recent comments

- whistleblow.....

2 hours 17 min ago - demosocialism....

11 hours 30 min ago - front cover up....

11 hours 44 min ago - the trick....

22 hours 30 min ago - bibi's wants.....

1 day 4 hours ago - gas snap....

1 day 7 hours ago - challenge....

1 day 8 hours ago - too late....

1 day 9 hours ago - spilling....

1 day 10 hours ago - US bullshit.....

1 day 10 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

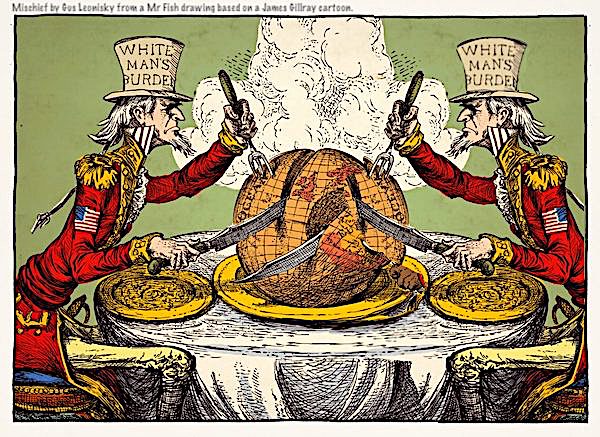

with friends like these….

THE USA SPY ON OUR [French/EU] COMPANIES AND WAGE AN ECONOMIC WAR on us - Ali Laïdi — May 7, 2022

Ali Laïdi is one of France's foremost specialists in economic warfare. He explains here how the United States ... abuse their dominant position, to economically tame the world. Between espionage and extraterritoriality, all means are good to ensure the monopoly of power. It would be very naive to believe, in this type of balance of power, that our allies are necessarily our friends!

SEE MORE:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Hnm-lLER-s

(Get Jules Letambour to translate for you)

See also: https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/36561

Meanwhile:

Very rarely, you read a book that inspires you to see a familiar story in an entirely different way. So it was with Adam Tooze’s astonishing economic history of World War II, The Wages of Destruction. And so it is again with his economic history of the First World War and its aftermath, The Deluge. They amount together to a new history of the 20th century: the American century, which according to Tooze began not in 1945 but in 1916, the year U.S. output overtook that of the entire British empire.

Yet Tooze's perspective is anything but narrowly American. His planetary history encompasses democratization in Japan and price inflation in Denmark; the birth of the Argentine far right as well as the Bolshevik seizure of power in Russia. The two books narrate the arc of American economic supremacy from its beginning to its apogee. It is both ominous and fitting that the second volume of the story was published in 2014, the year in which—at least by one economic measure—that supremacy came to an end.

“Britain has the earth, and Germany wants it.” Such was Woodrow Wilson’s analysis of the First World War in the summer of 1916, as recorded by one of his advisors. And what about the United States? Before the 1914 war, the great economic potential of the U.S. was suppressed by its ineffective political system, dysfunctional financial system, and uniquely violent racial and labor conflicts. “America was a byword for urban graft, mismanagement and greed-fuelled politics, as much as for growth, production, and profit,” Tooze writes.

The United States might claim a broader democracy than those that prevailed in Europe. On the other hand, European states mobilized their populations with an efficiency that dazzled some Americans (notably Theodore Roosevelt) and appalled others (notably Wilson). The magazine founded by pro-war intellectuals in 1914, The New Republic, took its title precisely because its editors regarded the existing American republic as anything but the hope of tomorrow.

Yet as World War I entered its third year—and the first year of Tooze’s story—the balance of power was visibly tilting from Europe to America. The belligerents could no longer sustain the costs of offensive war. Cut off from world trade, Germany hunkered into a defensive siege, concentrating its attacks on weak enemies like Romania. The Western allies, and especially Britain, outfitted their forces by placing larger and larger war orders with the United States. In 1916, Britain bought more than a quarter of the engines for its new air fleet, more than half of its shell casings, more than two-thirds of its grain, and nearly all of its oil from foreign suppliers, with the United States heading the list. Britain and France paid for these purchases by floating larger and larger bond issues to American buyers—denominated in dollars, not pounds or francs. “By the end of 1916, American investors had wagered two billion dollars on an Entente victory,” computes Tooze (relative to America’s estimated GDP of $50 billion in 1916, the equivalent of $560 billion in today’s money).

That staggering quantity of Allied purchases called forth something like a war mobilization in the United States. American factories switched from civilian to military production; American farmers planted food and fiber to feed and clothe the combatants of Europe. But unlike in 1940-41, the decision to commit so much to one side’s victory in a European war was not a political decision by the U.S. government. Quite the contrary: President Wilson wished to stay out of the war entirely. He famously preferred a “peace without victory.” The trouble was that by 1916, the U.S. commitment to Britain and France had grown—to borrow a phrase from the future—too big to fail.

Tooze's Wilson is no dreamy idealist. His animating idea was a startling vision of U.S. exceptionalism.

Tooze’s portrait of Woodrow Wilson is one of the most arresting novelties of his book. His Wilson is no dreamy idealist. The president’s animating idea was an American exceptionalism of a now-familiar but then-startling kind. His Republican opponents—men like Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and Elihu Root—wished to see America take its place among the powers of the earth. They wanted a navy, an army, a central bank, and all the other instrumentalities of power possessed by Britain, France, and Germany. These political rivals are commonly derided as “isolationists” because they mistrusted the Wilson’s League of Nations project. That’s a big mistake. They doubted the League because they feared it would encroach on American sovereignty. It was Wilson who wished to remain aloof from the Entente, who feared that too close an association with Britain and France would limit American options. This aloofness enraged Theodore Roosevelt, who complained that the Wilson-led United States was “sitting idle, uttering cheap platitudes, and picking up [European] trade, whilst they had poured out their blood like water in support of ideals in which, with all their hearts and souls, they believe.” Wilson was guided by a different vision: Rather than join the struggle of imperial rivalries, the United States could use its emerging power to suppress those rivalries altogether. Wilson was the first American statesman to perceive that the United States had grown, in Tooze’s words, into “a power unlike any other. It had emerged, quite suddenly, as a novel kind of ‘super-state,’ exercising a veto over the financial and security concerns of the other major states of the world.”

Wilson hoped to deploy this emerging super-power to enforce an enduring peace. His own mistakes and those of his successors doomed the project, setting in motion the disastrous events that would lead to the Great Depression, the rise of fascism, and a second and even more awful world war.

What went wrong? “When all is said and done,” Tooze writes, “the answer must be sought in the failure of the United States to cooperate with the efforts of the French, British, Germans and the Japanese [leaders of the early 1920s] to stabilize a viable world economy and to establish new institutions of collective security. … Given the violence they had already experienced and the risk of even greater future devastation, France, Germany, Japan, and Britain could all see this. But what was no less obvious was that only the US could anchor such a new order.” And that was what Americans of the 1920s and 1930s declined to do—because doing so implied too much change at home for them: “At the hub of the rapidly evolving, American-centered world system there was a polity wedded to a conservative vision of its own future.”

...

Grant rightly points out that wars are usually followed by economic downturns. Such a downturn occurred in late 1918-early 1919. “Within four weeks of the … Armistice, the [U.S.] War Department had canceled $2.5 billion of its then outstanding $6 billion in contracts; for perspective, $2.5 billion represented 3.3 percent of the 1918 gross national product,” he observes. Even this understates the shock, because it counts only Army contracts, not Navy ones. The postwar recession checked wartime inflation, and by March 1919, the U.S. economy was growing again.

As the economy revived, workers scrambled for wage increases to offset the price inflation they’d experienced during the war. Monetary authorities, worried that inflation would revive and accelerate, made the fateful decision to slam the credit brakes, hard. Unlike the 1918 recession, that of 1920 was deliberately engineered. There was nothing invisible about it. Nor did the depression “cure itself.” U.S. officials cut interest rates and relaxed credit, and the economy predictably recovered—just as it did after the similarly inflation-crushing recessions of 1974-75 and 1981-82.

...

Tooze’s story ends where our modern era starts: with the advent of a new European order—liberal, democratic, and under American protection. Yet nothing lasts forever. The foundation of this order was America’s rise to unique economic predominance a century ago. That predominance is now coming to an end as China does what the Soviet Union and Imperial Germany never could: rise toward economic parity with the United States. That parity has not, in fact, yet arrived, and the most realistic measures suggest that the moment of parity won’t arrive until the later 2020s. Perhaps some unforeseen disruption in the Chinese economy—or some unexpected acceleration of American prosperity—will postpone the moment even further. But it is coming, and when it does, the fundamental basis of world-power politics over the past 100 years will have been removed. Just how big and dangerous a change that will be is the deepest theme of Adam Tooze's profound and brilliant grand narrative.

READ MORE:

ONE MUST SEE THAT THE ONLY WAY THE USA CAN SUSTAIN THEIR "LIFESTYLE" is by robbing everyone else....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE ..... NOW.....

- By Gus Leonisky at 8 May 2022 - 9:03pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

from bad to worse…….

NEW YORK - With the worst start for the stock market in 80-plus years, the highest inflation in 40-plus years, the largest single interest rate hike in 20-plus years, as well as the dimmest public view of the US economy in 10-plus years, there is no surprise that a feeling of economic doom is going around in this country, CNN reported on Friday.

"And while he'll cheer stronger-than-expected new job growth data released (on) Friday, there's very little (US) President Joe Biden or anyone else can do but sit back and watch like the rest of us," said the report.

Energy prices are set by the OPEC, which isn't increasing oil production to anybody's liking quite yet; the interest rate hike announced on Wednesday by the Federal Reserve, which operates independently from the White House, will make it harder for home and car buyers and businesses to get access to cheap money, according to the report.

The Fed's most recent rate hike of half a percentage point is large, which helped push stocks lower on Thursday, but the Fed could raise its rates to at least 3 percent by the end of the year to combat inflation, said the report.

"Higher rates could be good for savers" and "challenge the stock market," which has "become accustomed to -- if not addicted to -- easy money," added CNN, noting that a majority of US adults in a new CNN poll said the president's policies have hurt the economy, and 8 in 10 said the government isn't doing enough to combat inflation.

READ MORE:

https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202205/07/WS6275cbe4a310fd2b29e5b2b1.html

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++