Search

Recent comments

- saint rube....

6 min 45 sec ago - patience....

2 hours 5 min ago - pretending....

3 hours 32 min ago - stenography.....

17 hours 49 min ago - black....

17 hours 47 min ago - concessions.....

18 hours 49 min ago - starmerring....

22 hours 54 min ago - unreal estates....

1 day 2 hours ago - nuke tests....

1 day 2 hours ago - negotiations....

1 day 2 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

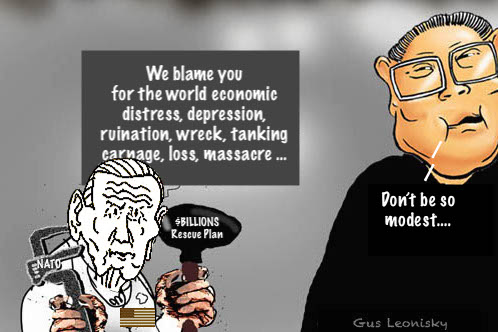

Joe the plumber was about to flush billions down the toilet….

In response to the Trump administration's trade war that began in 2018, at the same time that China was raising tariffs to retaliate against the United States, it was reducing its tariffs on imports from most of the rest of the world. China lowered its applied MFN tariffs from 8.0 percent at the kickoff of the trade war to 6.6 percent by the time the Phase One agreement was signed, in January 2020.

What happened next to those tariffs is worth investigating, however, especially as China subsequently bought none of the additional $200 billion of US exports promised in the Phase One agreement over 2020–21. In the deal, China did not agree to remove its tariffs on US exports to encourage purchases of US goods. (Beijing did establish an ad hoc exclusion process whereby Chinese firms could ask the Ministry of Finance to exclude tariffs from their purchases.) Nevertheless, China could have indirectly incentivized buying US exports—by, for example, raising its tariffs on imports from third countries that it had lowered during the trade war.

For the most part, China did not raise those tariffs. Its average applied MFN tariff held steady at 6.6 percent over 2020–21. And on January 2022, the suite of China's tariff changes—decreasing import duties on 347 products and increasing them on 21 others[4]—caused its average applied MFN tariff to fall slightly, from 6.6 to 6.5 percent.

Yet, focusing on average tariffs misses out on these important examples of China's very active use of trade policy to mitigate the effect of changing prices at home. Even with pork, China did not appear to break the rules in either 2020 or 2022, as its legal commitment at the WTO was not to raise its tariff above 12 percent.

For such a large country in the trading system, there is a better way. The rest of the world wants China to bind its tariffs for products like pork at a lower level. Then, when tough times emerge for either its consumers (as in 2020) or farmers (as in 2022), Beijing should turn to its domestic policies to help mitigate the effects. Relying on tariff changes to help those groups ends up shifting more of the policy's cost onto the rest of the world.

THE PROBLEM WITH IGNORING CHINA'S EXPORT POLICIESThe implications are similar for China's use of export policies. When China joined the WTO, in 2001, it committed to limit its use of export taxes. The steel export taxes it introduced in 2021 appear within those commitments and thus may not break any rules. (China faced legal challenges and lost formal WTO disputes over its export restrictions on raw materials and rare earths.) Yet, if China acting within the rules continues to hurt other countries, then the rules are a problem that the trading system must be modified to solve.

These other Chinese export restrictions are inconsistent with at least the spirit of trade rules. For example, China's failure to rebate steel product VATs that were rebated in the past (and continue to be rebated for other products) has the same immediate-term economic impact as a new export tax. Restricting fertilizer exports via unjustifiable inspections or government orders not to sell abroad is also problematic.

Irrespective of China, the fact that the WTO imposes fewer constraints on how and when countries restrict exports relative to imports is a historical flaw that needs to be fixed. In part, the loophole stems from the origins of the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). As the major economies at the time rarely used export taxes, trading partners did not bother negotiating rules to constrain them. (Indeed, export taxes are unconstitutional in the United States.[5])

On steel in particular, trade negotiators may need a further course correction. For nearly a decade, the United States, the European Union, and other economies have been increasingly worried about China's growing share of world production. Historically, however, the concern has been over the impact of China's export expansion on decreasing—not increasing—world steel prices. The United States responded with antidumping and countervailing duties to block most imports of Chinese steel by 2016. As steel is a commodity, however, China's exports went to third markets, third-country exports to the United States increased, and in 2018 the Trump administration imposed its infamous25 percent "national security" tariffs, which mostly affected direct imports from US military allies. (The Biden administration has not removed that protection; it has simply rearranged it into a set of import-limiting quotas so that firms from the European Union, Japan, and the United Kingdomsuffer less from tariffs and instead share in the benefit from higher prices in the US market.)

The worry is whether steel trade policymakers continue to focus exclusively on fighting the last war. The industry needs to be greener, as suggested, by the recent US and EU initiative to negotiate a "global arrangement to address carbon intensity and global overcapacity." Yet, China's switch to export restrictions helps keep prices lower at home at the expense of the rest of the world. If disproportionately aimed at early-stage steel products, they could even act as a subsidy that aids Chinese downstream and steel-using industries, much like the OECD found China had done with its selective export taxes and VAT rebates for the aluminum value chain (OECD 2019).[6]

THE NEED TO REENGAGE WITH CHINA ON TRADEDespite ever-shrinking political will, there is an ever-growing list of economic reasons to reengage with China on trade. Whether on steel, on adjustments to a greener economy, or even on global food security, attempts to regularize future trade relations must grapple with the reality that China has become extraordinarily large and continues to use policies that other major economies do not. To much of the rest of the world, what matters most is not containing China but constraining the size and suddenness of the costs that its policy choices impose on people outside its borders.[7]

READ MORE:

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW...............

- By Gus Leonisky at 9 May 2022 - 12:43pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

economic wobbles….

There’s a critical question that flows from last week’s turmoil in equity and bond markets. What if the Federal Reserve actually is determined to drive inflation down to its target of two per cent on average over time even if it induces a recession?

If it were to do that – and with US headline inflation at 8.5 per cent it is more than arguable that it should do that, even if it forces the US into recession – then the 13-year near-unbroken run of sharemarkets fuelled by central bank liquidity and ultra-low-to-negative policy rates would be in serious jeopardy.

It would seem that financial markets, which initially greeted the Fed’s 50 basis point increase in the federal funds rate last with near-euphoric relief on Wednesday – relieved that it wasn’t a 75 basis point rise and that Jerome Powell seemed to have ruled out future rises of that magnitude -- came to more sober conclusions only a day later.

Whether it is in 50 basis point increments rather than 75 basis points, US rates are destined to rise to whatever level is required to choke off inflation.

The market had bounced almost three per cent on the Fed’s announcement but slumped 3.6 per cent a day later in the worst day’s trading since the onset of the pandemic in 2020. In the bond market, the world’s most important bond yield, the 10-year Treasury bond yield, spiked through 3 per cent and held above that level for the first time since it spiked briefly through 3 per cent in 2018.

The US sharemarket has now fallen nearly 10 per cent since the end of March and about 13 per cent from its high point in January. The Nasdaq index, heavily weighted towards technology stocks, is down more than 23 per cent so far this year.

If, as investors seem to have concluded last Thursday, the Fed is determined to quash inflation even at the cost of a recession, there is no relief in sight and no floor under a market that has been propped up since the financial crisis (and turbocharged during the pandemic) by unprecedented central bank policies.

Quantitative easing – the buying of bonds and other securitised debt – and low-to-negative interest rates have encouraged investors into taking ever more risk in pursuit of positive returns since the 2008 financial crisis. Policies put in place to respond to a crisis were largely left in place even when the crisis had clearly passed.

What had been unconventional became the norm in the major economies – the US, Europe and Japan – because economic growth was, for most of the post-crisis period, anaemic and inflation, ironically, almost non-existent. The key banks, and their peers elsewhere, doubled down when the pandemic emerged.

Thus, since 2008, investors have had a rising floor and a safety net under markets underwritten by the central bankers.

Global supply chain shortages that the Fed thought last year would be transitory are, however (thanks to widespread lockdowns in China as it pursues its “zero COVID” strategy) continuing and, with the impact on energy prices of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, contributing to the highest inflation rates in 40 years.

If, as investors seem to have concluded last Thursday, the Fed is determined to quash inflation even at the cost of a recession, there is no relief in sight and no floor under a market that has been propped up since the financial crisis by unprecedented central bank policies.

While there is some expectation that this week’s US April CPI numbers will show a slight fall from the 8.5 per cent recorded in March, an inflation rate that remains above 8 per cent gives the Fed no room to finesse its monetary policies.

It will have to tighten financial conditions severely regardless of the consequences for the economy or investors. The last time it tried to raise rates and back out of its quantitative easing program the markets went into a tailspin and it backed off. Inflation during that episode in late 2018 was, however, only about two per cent.

READ MORE:

https://www.smh.com.au/business/markets/markets-are-wobbling-and-more-pain-could-be-on-the-horizon-20220509-p5ajn3.html

READ FROM TOP.

RAISING INTEREST RATES WON'T WORK AS inflation is presently driven by rarity of ESSENTIAL supplies rather than over-demand from the populace... "LET'S GIVE THEM CAKE" won't work.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW ######################