Search

Recent comments

- dumb blonde....

1 hour 30 min ago - unhealthy USA....

2 hours 3 min ago - it's time....

2 hours 25 min ago - pissing dick....

2 hours 44 min ago - landings.....

2 hours 55 min ago - sicko....

15 hours 44 min ago - brink...

16 hours 23 sec ago - gigafactory.....

17 hours 46 min ago - military heat....

18 hours 29 min ago - arseholic....

23 hours 12 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

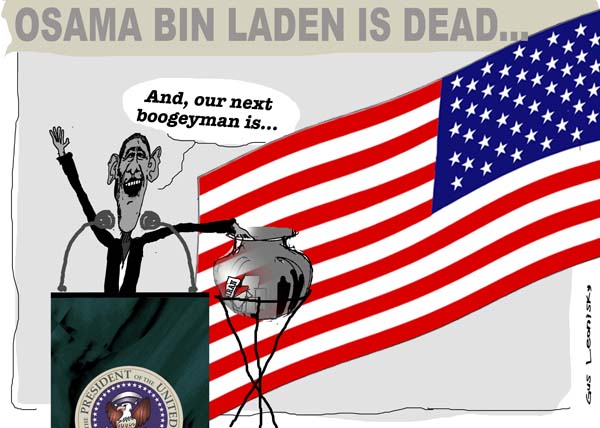

a conga line of foes, enemies and made-up demons to have an excuse for our butt cramp…...

Any government that is a national-security state needs big official enemies — scary ones, ones that will cause the citizenry to continue supporting not only the continued existence of a national-security state form of government but also ever-growing budgets for it and its army of voracious “defense” contractors.

That’s, of course, what the current brouhaha about Russia is all about. It’s really a replay of the Cold War decades, when Americans were made to believe that the Reds were coming to get them, take over the federal government and the public schools, and indoctrinate everyone into loving communism and socialism.

BY Jacob Hornberger

In those Cold War years, Americans citizens were so scared of the Reds that they were willing to ignore — or even support — the dark-side powers that were being wielded and exercised by the Pentagon, the CIA, and the NSA, which are the three principal components of the national-security establishment. The idea was that if the U..S. government failed to adopt the same dark-side totalitarian-type powers, such as assassination and torture, that the Soviet Union and Red China were wielding and exercising, the United States would end up falling to the Reds and becoming communist.

The Cold War notion was that there was an international communist conspiracy to take over the world that was supposedly based in Moscow — yes, the same Moscow that is now being used, once again, to scare the dickens out of the American people.

Ironically, however, the American right wing, which was the leader of America’s anti-communist crusade during the Cold War, was teaching that socialism was an inherently defective paradigm. They would cite free-market economists like Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, and Milton Friedman to show that socialism was doomed to fail.

Alas, American conservatives were never able to see the contradiction in their position. On the one hand, they were claiming that socialism was an inherently defective system that was doomed to fail. On the other hand, they were claiming that America and the rest of the world was in grave danger of falling to the supposed international communist/socialist conspiracy to take over the world that was supposedly based in Moscow.

The fact is that there was never any danger whatsoever of a Soviet or Chinese invasion and takeover of the United States. It was always an overblown threat designed to keep Americans afraid — and to keep the national-security establishment and its voracious army of “defense” contractors in power and in “high cotton.”

Oh sure, there was always the possibility of nuclear war, but that was the last thing that China or Russia wanted, especially given the vast superiority of America’s nuclear arsenal. It’s worth mentioning though that the Pentagon and the CIA constantly claimed, falsely, that the Soviet nuclear arsenal was vastly superior to that of the United States. Again, they had to keep Americans afraid as a way to maintain their power and their budgets.

When the Cold War was suddenly over, the Pentagon, the CIA, and the NSA freaked out. That was the last thing they expected or wanted. They needed the Cold War. How else could they keep Americans afraid? What if Americans began demanding the restoration of their founding governmental system of a limited-government republic, which would necessarily entail the dismantling of the national-security state form of governmental structure?

That’s when they turned on their old partner and ally, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. Throughout the 1990s, Saddam became the new official enemy. Day after day, it was “Saddam! Saddam! Saddam! He is the new Hitler! He is coming to get us with his WMDs!” And the vast majority of Americans bought into the new official scaremongering, no matter how ridiculous it was.

Meanwhile, however, the Pentagon and the CIA were going into the Middle East with a campaign of death and destruction, one that would end up producing another big scary official enemy — terrorism — and, to a certain extent, Islam. Even though commentators continually warned the Pentagon and the CIA that their deadly and destructive interventionist campaign would produce terrorist blowback, the Pentagon and the CIA continued pressing forward, with the result being the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center in 1993, the USS Cole, the U.S. embassies in East Africa, the 9/11 attacks, and the post-9/11 attacks. Americans now had a new official enemy — possibly one than was scarier than communism — and the national-security state was off to the races with more power and more money.

Then came the invasions and occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq as part of the Global War on Terrorism. They milked that for some 20 years, keeping Americans deathly afraid of the terrorists and the Muslims, who had supposedly been planning the takeover of America as part of a centuries-old conspiracy to establish a worldwide caliphate, one that would require every American citizen to live under Sharia law.

But throughout the entire war on terrorism and war on Islam, they never gave up on restoring China and Russia as big, scary official Cold War enemies. That’s what is going on today. The Pentagon, the CIA, and the NSA know that Americans are losing some of their fear of the terrorists and the Muslims, especially now that the Pentagon and the CIA are no longer killing people in Afghanistan.

Their big problem, however, is that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is proving that Russia is a second-rate military power, one that can’t even conquer a third-rate power like Ukraine. At the risk of belaboring the obvious, it’s hard to convince people that America is in grave danger of falling to the Reds — I mean, the Russians — when a crooked and corrupt third-rate regime in Ukraine isn’t even falling to the Russians.

Where do the Pentagon, the CIA, and the NSA go from here? They will undoubtedly continue indoctrinating Americans into living in deep fear of the Russkies and the Chinese Reds. Don’t be surprised if they gin up another crisis with North Korea, which is always a good-standby official enemy. There is always Iran, of course, or Cuba, Venezuela, or Nicaragua — maybe even (communist) Vietnam again — given that fear of the Reds is always a good one on which to rely. And since they are still killing people in Iraq and the rest of the Middle East, as well as in Africa, there is always the possibility of terrorist blowback that will reinvigorate the Global War on Terrorism and Islam.

The solution to all this official-enemy mayhem? Americans need to overcome the fear of official enemies that has been inculcated into them by the national-security establishment as part of their decades-old crooked and corrupt racket. Once that happens, it will be possible to restore America’s founding governmental system of a limited-government republic and get back on the road to liberty, peace, prosperity, and harmony with the people of the world.

Purchase Jacob Hornberger’s new book An Encounter with Evil: The Abraham Zapruder Story at Amazon: $9.95 Kindle version, $14.95 print version.

(Please note that we "borrow the good words" of people, say Hornberger's, and if they have more goos stories to "sell", may as well tell you where to find them).

READ MORE:

https://www.fff.org/2022/06/15/an-endless-stream-of-scary-official-enemies/

NOTE: WE'VE BEEN ON THE CASE SINCE 2011.... SEE:

https://www.yourdemocracy.net.au/drupal/node/12413

- By Gus Leonisky at 18 Jun 2022 - 8:29pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the explosive profits of wars….

back in September 23, 2021......

by William D. Hartung

The costs and consequences of America’s twenty-first-century wars have by now been well-documented — a staggering $8 trillion in expenditures and more than 380,000 civilian deaths, as calculated by Brown University’s Costs of War project. The question of who has benefited most from such an orgy of military spending has, unfortunately, received far less attention.

Corporations large and small have left the financial feast of that post-9/11 surge in military spending with genuinely staggering sums in hand. After all, Pentagon spending has totaled an almost unimaginable $14 trillion-plus since the start of the Afghan War in 2001, up to one-half of which (catch a breath here) went directly to defense contractors.

‘The Purse is Now Open’

The political climate created by the Global War on Terror, or GWOT, as Bush administration officials quickly dubbed it, set the stage for humongous increases in the Pentagon budget. In the first year after the 9/11 attacks and the invasion of Afghanistan, defense spending rose by more than 10% and that was just the beginning. It would, in fact, increase annually for the next decade, which was unprecedented in American history.

The Pentagon budget peaked in 2010 at the highest level since World War II — over $800 billion, substantially more than the country spent on its forces at the height of the Korean or Vietnam Wars or during President Ronald Reagan’s vaunted military buildup of the 1980s.

And in the new political climate sparked by the reaction to the 9/11 attacks, those increases reached well beyond expenditures specifically tied to fighting the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. As Harry Stonecipher, then vice president of Boeing, told the The Wall Street Journal in an October 2001 interview, “The purse is now open… [A]ny member of Congress who doesn’t vote for the funds we need to defend this country will be looking for a new job after next November.”

Stonecipher’s prophesy of rapidly rising Pentagon budgets proved correct. And it’s never ended. The Biden administration is anything but an exception. Its latest proposal for spending on the Pentagon and related defense work like nuclear warhead development at the Department of Energy topped $753 billion for FY2022. And not to be outdone, the House and Senate Armed Services Committees have already voted to add roughly $24 billion to that staggering sum.

Who Benefitted?

The benefits of the post-9/11 surge in Pentagon spending have been distributed in a highly concentrated fashion. More than one-third of all contracts now go to just five major weapons companies — Lockheed Martin, Boeing, General Dynamics, Raytheon, and Northrop Grumman. Those five received more than $166 billion in such contracts in fiscal year 2020 alone.

To put such a figure in perspective, the $75 billion in Pentagon contracts awarded to Lockheed Martin that year was significantly more than one and one-half times the entire 2020 budget for the State Department and the Agency for International Development, which together totaled $44 billion.

While it’s true that the biggest financial beneficiaries of the post-9/11 military spending surge were those five weapons contractors, they were anything but the only ones to cash in. Companies benefiting from the buildup of the past 20 years also included logistics and construction firms like Kellogg, Brown & Root (KBR) and Bechtel, as well as armed private security contractors like Blackwater and Dyncorp.

The Congressional Research Service estimates that in FY2020 the spending for contractors of all kinds had grown to $420 billion, or well over half of the total Pentagon budget. Companies in all three categories noted above took advantage of “wartime” conditions — in which both speed of delivery and less rigorous oversight came to be considered the norms — to overcharge the government or even engage in outright fraud.

The best-known reconstruction and logistics contractor in Iraq and Afghanistan was Halliburton, through its KBR subsidiary. At the start of both the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, Halliburton was the recipient of the Pentagon’s Logistics Civil Augmentation Program contracts.

Those open-ended arrangements involved coordinating support functions for troops in the field, including setting up military bases, maintaining equipment, and providing food and laundry services. By 2008, the company had received more than $30 billion for such work.

Halliburton’s role would prove controversial indeed, reeking as it did of self-dealing and blatant corruption. The notion of privatizing military-support services was first initiated in the early 1990s by Dick Cheney when he was secretary of defense in the George H.W. Bush administration and Halliburton got the contract to figure out how to do it.

I suspect you won’t be surprised to learn that Cheney then went on to serve as the CEO of Halliburton until he became vice president under George W. Bush in 2001. His journey was a (if not the) classic case of that revolving door between the Pentagon and the defense industry, now used by so many government officials and generals or admirals, with all the obvious conflicts-of-interest it entails.

Once it secured its billions for work in Iraq, Halliburton proceeded to vastly overcharge the Pentagon for basic services, even while doing shoddy work that put U.S. troops at risk — and it would prove to be anything but alone in such activities.

tarting in 2004, a year into the Iraq War, the Special Inspector General for Iraq Reconstruction, a congressionally mandated body designed to root out waste, fraud, and abuse, along with Congressional watchdogs like Rep. Henry Waxman (D-CA), exposed scores of examples of overcharging, faulty construction, and outright theft by contractors engaged in the “rebuilding” of that country.

Again, you undoubtedly won’t be surprised to find out that relatively few companies suffered significant financial or criminal consequences for what can only be described as striking war profiteering. The congressional Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan estimated that, as of 2011, waste, fraud, and abuse in the two war zones had already totaled $31 billion to $60 billion.

A case in point was the International Oil Trading Company, which received contracts worth $2.7 billion from the Pentagon’s Defense Logistics Agency to provide fuel for U.S. operations in Iraq. An investigation by Waxman, chair of the House Government Oversight and Reform Committee, found that the firm had routinely overcharged the Pentagon for the fuel it shipped into Iraq, making more than $200 million in profits on oil sales of $1.4 billion during the period from 2004 to 2008.

More than a third of those funds went to its owner, Harry Sargeant III, who also served as the finance chairman of the Florida Republican Party. Waxman summarized the situation this way: “The documents show that Mr. Sargeant’s company took advantage of U.S. taxpayers. His company had the only license to transport fuel through Jordan, so he could get away with charging exorbitant prices. I’ve never seen another situation like this.”

A particularly egregious case of shoddy work with tragic human consequences involved the electrocution of at least 18 military personnel at several bases in Iraq from 2004 on. This happened thanks to faulty electrical installations, some done by KBR and its subcontractors.

An investigation by the Pentagon’s Inspector General found that commanders in the field had “failed to ensure that renovations… had been properly done, the Army did not set standards for jobs or contractors, and KBR did not ground electrical equipment it installed at the facility.”

The Afghan “reconstruction” process was similarly replete with examples of fraud, waste, and abuse. These included a U.S.-appointed economic task force that spent $43 million constructing a gas station essentially in the middle of nowhere that would never be used, another $150 million on lavish living quarters for U.S. economic advisors, and $3 million for Afghan police patrol boats that would prove similarly useless.

Perhaps most disturbingly, a congressional investigation found that a significant portion of $2 billion worth of transportation contracts issued to U.S. and Afghan firms ended up as kickbacks to warlords and police officials or as payments to the Taliban to allow large convoys of trucks to pass through areas they controlled, sometimes as much as $1,500 per truck, or up to half a million dollars for each 300-truck convoy.

In 2009, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton stated that “one of the major sources of funding for the Taliban is the protection money” paid from just such transportation contracts.

A Two-Decade Explosion of Corporate Profits

A second stream of revenue for corporations tied to those wars went to private security contractors, some of which guarded U.S. facilities or critical infrastructure like Iraqi oil pipelines.

The most notorious of them was, of course, Blackwater, a number of whose employees were involved in a 2007 massacre of 17 Iraqis in Baghdad’s Nisour Square. They opened fire on civilians at a crowded intersection while guarding a U.S. Embassy convoy. The attack prompted ongoing legal and civil cases that continued into the Trump era, when several perpetrators of the massacre were pardoned by the president.

In the wake of those killings, Blackwater was rebranded several times, first as XE Services and then as Academii, before eventually merging with Triple Canopy, another private contracting firm.

Blackwater founder Erik Prince then separated from the company, but he has since recruited private mercenaries on behalf of the United Arab Emirates for deployment to the civil war in Libya in violation of a United Nations arms embargo. Prince also unsuccessfully proposed to the Trump administration that he recruit a force of private contractors meant to be the backbone of the U.S. war effort in Afghanistan.

Another task taken up by private firms Titan and CACI International was the interrogation of Iraqi prisoners. Both companies had interrogators and translators on the ground at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, a site where such prisoners were brutally tortured.

The number of personnel deployed and the revenues received by security and reconstruction contractors grew dramatically as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wore on. The Congressional Research Service estimated that by March 2011 there were more contractor employees in Iraq and Afghanistan (155,000) than American uniformed military personnel (145,000).

In its August 2011 final report, the Commission on Wartime Contracting in Iraq and Afghanistan put the figure even higher, stating that “contractors represent more than half of the U.S. presence in the contingency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, at times employing more than a quarter-million people.”

While an armed contractor who had served in the Marines could earn as much as $200,000 annually in Iraq, about three-quarters of the contractor work force there was made up of people from countries like Nepal or the Philippines, or Iraqi citizens. Poorly paid, at times they received as little as $3,000 per year.

A 2017 analysis by the Costs of War project documented “abysmal labor conditions” and major human rights abuses inflicted on foreign nationals working on U.S.-funded projects in Afghanistan, including false imprisonment, theft of wages, and deaths and injuries in areas of conflict.

With the U.S. military in Iraq reduced to a relatively modest number of armed “advisors” and no American forces left in Afghanistan, such contractors are now seeking foreign clients. For example, a U.S. firm — Tier 1 Group, which was founded by a former employee of Blackwater — trained four of the Saudi operatives involved in the murder of Saudi journalist and U.S. resident Jamal Khashoggi, an effort funded by the Saudi government.

As the The New York Times noted when it broke that story, “Such issues are likely to continue as American private military contractors increasingly look to foreign clients to shore up their business as the United States scales back overseas deployments after two decades of war.”

Add in one more factor to the two-decade “war on terror” explosion of corporate profits. Overseas arms sales also rose sharply in this era. The biggest and most controversial market for U.S. weaponry in recent years has been the Middle East, particularly sales to countries like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which have been involved in a devastating war in Yemen, as well as fueling conflicts elsewhere in the region.

Donald Trump made the most noise about Middle East arms sales and their benefits to the U.S. economy. However, the giant weapons-producing corporations actually sold more weaponry to Saudi Arabia, on average, during the Obama administration, including three major offers in 2010 that totaled more than $60 billion for combat aircraft, attack helicopters, armored vehicles, bombs, missiles, and guns — virtually an entire arsenal.

Many of those systems were used by the Saudis in their intervention in Yemen, which has involved the killing of thousands of civilians in indiscriminate air strikes and the imposition of a blockade that has contributed substantially to the deaths of nearly a quarter of a million people to date.

Forever War Profiteering?

Reining in the excess profits of weapons contractors and preventing waste, fraud, and abuse by private firms involved in supporting U.S. military operations will ultimately require reduced spending on war and on preparations for war. So far, unfortunately, Pentagon budgets only continue to rise and yet more money flows to the big five weapons firms.

To alter this remarkably unvarying pattern, a new strategy is needed, one that increases the role of American diplomacy, while focusing on emerging and persistent non-military security challenges. “National security” needs to be redefined not in terms of a new “cold war” with China, but to forefront crucial issues like pandemics and climate change.

It’s time to put a halt to the direct and indirect foreign military interventions the United States has carried out in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Somalia, Yemen, and so many other places in this century. Otherwise, we’re in for decades of more war profiteering by weapons contractors reaping massive profits with impunity.

Copyright 2021 William D. Hartung

William D. Hartung, a TomDispatch regular, is the director of the Arms and Security Program at the Center for International Policy. This piece is adapted from a new report he wrote for the Center for International Policy and the Costs of War Project at Brown University, “Profits of War: Corporate Beneficiaries of the post-9/11 Pentagon Spending Surge.”

READ MORE:

https://consortiumnews.com/2021/09/23/how-corporations-won-the-war-on-terror/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW.............

the heartland explained…...

REPEAT:

the heartland explained...https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14650040802578658

The US Grand Strategy and the Eurasian Heartland in the Twenty-First Century

Pages 26-46 | Published online: 21 Feb 2009

Emre İşeri

From an offensive realist theoretical approach, this paper assumes that great powers are always looking for opportunities to attain more power in order to feel more secure. This outlook has led me to assert that the main objective of the US grand strategy in the twenty-first century is primacy or global hegemony. I have considered the US grand strategy as a combination of wartime and peacetime strategies and argued that the Caspian region and its hinterland, where I call the Eurasian Heartland, to use the term of Sir Halford Mackinder, has several geo-strategic dimensions beyond its wide-rich non-OPEC untapped hydro-carbon reserves, particularly in Kazakhstan. For my purposes, I have relied on both wartime strategy (US-led Iraq war) and peacetime strategy of supporting costly Baku-Tbilis-Ceyhan (BTC) to integrate regional untapped oil reserves, in particular Kazakh, into the US-controlled energy market to a great extent. This pipeline's contribution to the US grand strategy is assessed in relation to potential Eurasian challengers, Russia and China. The article concludes with an evaluation of the prospects of the US grand strategy in the twenty-first century.

INTRODUCTION

From an offensive realist theoretical approach, this paper assumes that great powers, for my purposes the US, are always looking for opportunities to attain more power in order to feel more secure. In other words, great powers have a natural inclination to maximise their power. One of the main reasons for this analytical footing is based on my observation that this theory has a great deal of explanatory power for understanding US foreign policy in the post-9/11 period. This outlook has led me to assert that the main objective of US grand strategy is primacy or global hegemony.

Even though the region surrounding the Caspian Sea, where I call the Eurasian Heartland 1 , is not a target of the ‘war on terror’, political control of this region's hydrocarbon resources and their transportation routes has several geo-strategic dimensions beyond energy considerations. From the perspective of US policy-making elites 2 , the Caspian region's geo-strategic dimensions for the United States are not restricted to energy security issues; they have implications for the grand strategy of the United States in the twenty-first century. In that regard, the US not only aims to politically control regional energy resources, in particular Kazakh oil, but also check potential challengers to its grand strategy such as China and Russia. One should note that analysis of grand strategies of those states is beyond the scope of this article, therefore, they are treated as potential challengers, rather than great powers, and their positions in the Caspian energy game has been elaborated in that sense.

In the first part of the paper, I will talk about my offensive realist theoretical approach. In addition to its assumptions, its limitations will be noted. In the second part, I will define the concept of grand strategy as the combination of wartime and peacetime strategies and analyse US grand strategy in the twenty-first century in that respect. In the third part, geo-strategic dimensions of the Eurasian Heartland for the US grand strategy will be analysed in relation to Eurasian challengers. The significance of politically controlling Kazakh oil resources will also be underlined. In the fourth part, Russia's interests and policies on Caspian hydro-carbon resources will be analysed in relation to US interests. In the fifth part, China's energy needs and its Caspian pipeline politics will be analysed in relation to US-controlled international oil markets. It will be concluded by indicating the significance of ensuring stability of the international oil markets for the success of US grand strategy in the twenty-first century.

OFFENSIVE REALISM

The offensive realist point of view contends that the ultimate goal of states is to achieve a hegemonic position in the international order. Hence, offensive realism claims that states always look for opportunities to gain more power in order to gain more security for an uncertain future. Until and unless they become the global hegemon, their search for increased power will continue. Offensive realism has been based on five assumptions: (1) The system is anarchic; (2) All great powers have some offensive military capabilities; (3) States can never be certain about other states' intentions; (4) States seek to survive; and (5) Great powers are rational actors or strategic calculators.

My approach is closer to the offensive realist position mainly because of my supposition that, particularly after September 11, US behaviour conforms to the prognostications of offensive realist arguments. With the rhetoric of the ‘war on terror,’ the US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were apparent products of an offensive realist objective, namely to underpin the United States' sole super power status in the post−Cold War global order.

I assume that there is a direct link between the survival instincts of great powers and their aggressive behaviour. In that regard, we agree with Mearsheimer that “Great powers behave aggressively not because they want to or because they possess some inner drive to dominate, but because they have to seek more power if they maximize their odds of survival.” 3

One should be aware, however, that this power maximisation strategy has some limits. Structural limitations prevent states from expanding their hegemony to the entire globe. Hence, it is nearly impossible in today's world to become a true global hegemon. In order to make our point more tangible, we need to first take a look at the meaning of hegemon in relation to great powers:

A hegemon is a state that is so powerful that it dominates all other states in the system. No other state has the military wherewithal to put up a serious fight against it. In essence, a hegemon is the only great power in the system. A state that is substantially more powerful than the other great powers in the system is not a hegemon, because it faces, by definition, other great powers. 4

Pragmatically, it is nearly impossible for a great power to achieve global hegemony because there will always be competing great powers that have the potential to be the regional hegemon in a distinct geographical region. Clearly, geographical distance makes it more difficult for the potential global hegemon to exert its power on potential regional hegemons in other parts of the world. On the one hand, the ‘global hegemon’ must dominate the whole world. On the other hand, the ‘regional hegemon’ only dominates a distinct geographical area, a much easier task for a great power. For instance, the United States has been the regional hegemon in the Western hemisphere for about a century, but it has never become a true global hegemon because there have always been great powers in the Eastern hemisphere, such as Russia and China, which have potential to be regional hegemons in their geographical are. Since US policy-making elites have acknowledged that ‘stopping power of sea’ 5 restricts the US from projecting a sufficient amount of power in the distinct continent of Eurasia to become the global hegemon, they have been preparing their strategies to prevent emergence of regional hegemonies that have potential to challenge US grand strategy.

US GRAND STRATEGY IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Paul Kennedy's definition of ‘grand strategy’ that includes both wartime and peacetime objectives: “A true grand strategy was now to do with peace as much as (perhaps even more than) war. It was about the evolution and integration of policies that should operate for decades, or even for centuries. It did not cease at a war's end, nor commence at its beginning.” 6 Put simply, grand strategy is the synthesis of wartime and peacetime strategies. Even though they are separate, they interweave in many ways to serve the grand strategy.

Since the United States, which is the hegemonic power of capitalist core countries, has dominance over the global production structure, it is in its best interest to expand the global market for goods and services. For instance, free trade arrangements usually force developing (i.e., “third-world”) countries to export their raw materials without transforming them into completed products that can be sold in developed markets. Therefore, the global free market has long been the most viable strategy for acquiring raw materials in the eyes of the US policy-making elites. This is what Andrew J. Bacevich refers to when he talks about the US policy of imposing an ‘open world’ or ‘free world’ possessed with the knowledge and confidence that “technology endows the United States with a privileged position in that order, and the expectation that American military might will preserve order and enforce the rules.” 7 In other words, the principal interest of the US is the establishment of a secure global order in a context that enables the US-controlled capitalist modes of production to flourish throughout the globe without any obstacles or interruptions. This is also simply the case for the openness of oil trade. “In oil, as more generally, the forward deployment of military power to guarantee the general openness of international markets to the mutual benefit of all leading capitalist states remains at the core of US hegemony. An attempt to break this pattern, carve out protected spaces for the US economy and firms against other ‘national’ or ‘regional’ economies would undercut American leadership.” 8 Since the US imports energy resources from international energy markets, any serious threat to these markets is a clear threat to the interests of the United States. As Leon Fuerth indicates, “The grand strategy of the United States requires that it never lose the ability to respond effectively to any such threat.” 9

With the end of the presidency of Bill Clinton, George W. Bush took office in January 2001. People with backgrounds and experience in the oil industry dominated his cabinet's inner circle. Vice President Dick Cheney had served as the chief executive of the world's leading geophysics and oil services company, Halliburton, Inc. National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice (who later became the US Secretary of State) had served on the board of Chevron Corporation. As a Texan, George W. Bush himself had far-reaching oil experience, and Commerce Secretary Don Evans had served 16 years as the CEO of Tom Brown Inc., a large, independent energy company now based in Denver, after working for 10 years on its oil rigs. As William Engdahl has succinctly explained, “In short, the Bush administration which took office in January 2001, was steeped in oil and energy issues as no administration in recent US history had been. Oil and geopolitics were back at center stage in Washington.” 10

In the early days of the Bush administration, Vice President Dick Cheney was assigned the task of carrying out a comprehensive review of US energy policy. He presented the result, known as the National Energy Policy Report (NEPR) of May 2001, 11 to President Bush with the recommendation that energy security should immediately be made a priority of US foreign policy. In the NEPR, the growing dependency of the United States on oil imports for its energy needs was emphasised, and this was characterised as a significant problem. The National Energy Policy Report read, in part, “On our present course, America 20 years from now will import nearly two of every three barrels of oil – a condition of increased dependency on foreign powers that do not always have America's interests at heart.” 12 In other words, as William Engdahl sardonically observed, “A national government in control of its own ideas of national development might not share the agenda of ExxonMobil or ChevronTexaco or Dick Cheney.”13 In 2010, the United States will need an additional 50 million barrels of oil a day, 90 percent of which will be imported and thus under the control of foreign governments and foreign national oil companies. Therefore, given its strategic importance for a country's economy, it can be plausibly argued that oil (including its price, its flow, and its security) is more of a governmental matter than a private one. Despite the area's political and economic instabilities, the Middle East's untapped oil reserves are still the cheapest source of oil in the world; furthermore, they amount to two thirds of the world's remaining oil resources.

Thus, governmental intervention by the United States was required to secure the supply of Middle East oil to world markets. William Engdahl correctly notes that “with undeveloped oil reserves perhaps even larger than those of Saudi Arabia, Iraq had become an object of intense interest to Cheney and the Bush administration very early on.” 14 Iraq's authoritarian regime under Saddam Hussein was pursuing the idea of ‘national development,’ according to which state institutions would have full control over the extraction, production, and sale of oil. According to Michael Hirsh, “State control guarantees less efficiency in the exploration for oil, and in the extraction and refinement of fuel. Further, these state-owned companies do not divulge how much they really own, or what the production and exploration numbers are. These have become the new state secrets.” 15 From the perspective of US policy-making elites, the Iraqi oil reserves were too large and too valuable to be left to the control of Iraqi state-owned companies, hence, a regime change in Iraq was required.

“Several slogans have been offered to justify the Iraq War, but certainly one of the most peculiar is the idea proffered by Stanley Kurtz, Max Boot, and other neoconservative commentators who advocate military action and regime change as a part of their bold plan for democratic imperialism.”16 [Emphasis added.] However, it is dubious to what extent this neoconservative plan serves the purposes of American grand strategy. George Kennan, former head of policy planning in the US State Department, is often regarded as one of the key architects of US grand strategy in the post-war period. His candid advice to US leadership should be noted:

We have about 50 percent of the world's wealth, but only 6.3 percent of its population. In this situation, we cannot fail to be the object of envy and resentment. Our real task in the coming period is to devise a pattern of relationships, which will permit us to maintain this position of disparity. To do so, we will have to dispense with all sentimentality and daydreaming; and our attention will have to be concentrated everywhere on our immediate national objectives. We should cease to talk about vague and unreal objectives such as human rights, the raising of the living standards, and democratization. The day is not far off when we are going to have to deal in straight power concepts. The less we are then hampered by idealistic slogans, the better. 17 [Emphasis added.]

As Clark observes, “While the US has largely been able to avoid ‘straight power concepts’ for five decades, it has now become the only vehicle for which it can maintain its dominance. Indeed, Kennan's term ‘straight power’ is the appropriate description of current US geopolitical unilateralism.”18 Thus, the US's unilateral aggressive foreign policy in the post-9/11 period has led me to argue that the ultimate objective of US grand strategy is ‘primacy’ among competing visions 19 and what I understand from primacy is global hegemony or leadership. This aggressive strategy of the US to expand its hegemony to the globe was outlined in The National Security Strategy of the United States of America, published by the Bush Administration in September 2002, and it has come to be publicly known as the Bush Doctrine to form ‘coalitions of the willing’ under US leadership.

The United States has long maintained the option of pre-emptive actions to counter a sufficient threat to our national security … the case for taking anticipatory action to defend ourselves, even if uncertainty remains as the time and place of the enemy's attack. To forestall or prevent such hostile acts by our adversaries, the United States will, if necessary, act pre-emptively. 20

Those elements of the doctrine that scholars and analysts associated with empire-like tendencies were on full display in the build-up to the unilateral invasion of Iraq by the United States in 2003.

As Pepe Escobar notes, “The lexicon of the Bush doctrine of unilateral world domination is laid out in detail by the Project for a New American Century (PNAC), founded in Washington in 1997. The ideological, political, economic and military fundamentals of American foreign policy – and uncontested world hegemony – for the 21st century are there for all to see.” 21 The official credo of PNAC is to convene “the resolve to shape a new century favorable to American principles and interests”. 22 The origin of PNAC can be traced to a controversial defence policy paper drafted in February 1992 by then Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz and later softened by Vice President Dick Cheney which states that the US must be sure of “deterring any potential competitors from even aspiring to a larger regional or global role” 23 without mentioning the European Union, Russia, and China. Nevertheless, the document Rebuilding America's Defenses: Strategies, Forces and Resources for a New Century 24 released by PNAC gives a better understanding of the Bush administration's unilateral aggressive foreign policy and “this manifesto revolved around a geostrategy of US dominance – stating that no other nations will be allowed to ‘challenge’ US hegemony”. 25

From this perspective, it can be assumed that American wartime (the US-led wars in Afghanistan 26 , and Iraq) and peacetime (political support for costly Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline project) strategies all serve the US grand strategy in the twenty-first century. A careful eye will detect that all of these strategies have a common purpose of enhancing American political control over the Eurasian landmass and its hydrocarbon resources. As Fouskas and Gökay have observed,

As the only superpower remaining after the dismantling of the Soviet bloc, the United States is inserting itself into the strategic regions of Eurasia and anchoring US geopolitical influence in these areas to prevent all real and potential competitions from challenging its global hegemony. The ultimate goal of US strategy is to establish new spheres of influence and hence achieve a much firmer system of security and control that can eliminate any obstacles that stand in the way of protecting its imperial power. The intensified drive to use US military dominance to fortify and expand Washington's political and economic power over much of the world has required the reintegration of the post-Soviet space into the US-controlled world economy. The vast oil and natural gas resources of Eurasia are the fuel that is feeding this powerful drive, which may lead to new military operations by the United States and its allies against local opponents as well as major regional powers such as China and Russia. 27

At this point the question arises, what is the geo-strategic dimensions of the Eurasian Heartland and its energy resources for the US grand strategy in the twenty-first century?

GEO-STRATEGIC DIMENSIONS OF THE EURASIAN HEARTLAND

The Heartland Theory is probably the best-known geopolitical model that stresses the supremacy of land-based power to sea-based power. Sir Halford Mackinder, who was one of the most prominent geographers of his era, first articulated this theory with respect to ‘The Geographic Pivot of History’ in 1904, and it was later redefined in his paper entitled, Democratic Ideals and Reality(1919), in which “pivotal area” became “the Heartland.” According to Mackinder, the pivotal area or the Heartland is roughly Central Asia, from where horsemen spread out toward and dominated both the Asian and the European continents. While developing his ideas, Mackinder's main concern was to warn his compatriots about the declining naval power of the United Kingdom, which had been the dominant naval power since the age of the revolutionary maritime discoveries of the fifteenth century. He proceeded to expand on the possibility of consolidated land-based power that could allow a nation to control the Eurasian landmass between Germany and Central Siberia. If well served and supported by industry and by modern means of communication, a consolidated land power controlling the Heartland could exploit the region's rich natural resources and eventually ascend to global hegemony. Mackinder summed up his ideas with the following words: “Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland: Who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island (Europe, Arab Peninsula, Africa, South and East Asia), who rules the World-Island commands the World.” 28

The Heartland Theory provided the intellectual ground for the US Cold War foreign policy. Nicholas Spykman was among the most influential American political scientists in the 1940s. Spykman's Rimlands thesis was developed on the basis of Mackinder's Heartland concept. In contrast to Mackinder's emphasis on the Eurasian Heartland, Spykman offered the Rimlands of Eurasia – that is, Western Europe, the Pacific Rim and the Middle East. According to him, whoever controlled these regions would contain any emerging Heartland power. “Spykman was not the author of containment policy, that is credited to George Kennan, but Spykman's book, based on the Heartland thesis, helped prepare the US public for a post war world in which the Soviet Union would be restrained on the flanks.” 29 Hence, the US policy of containing the USSR dominated global geopolitics during the Cold War era under the guidance of ideas and theories first developed by Mackinder. In the 1988 edition of the annual report on US geopolitical and military policy entitled, The National Security Strategy of the United States of America, President Reagan summarised US foreign policy in the Cold War era with these words:

The first historical dimension of our strategy … is the conviction that the United States' most basic national security interests would be endangered if a hostile state or group of states were to dominate the Eurasian landmass – that part of the globe often referred to as the world's heartland … since 1945, we have sought to prevent the Soviet Union from capitalizing on its geostrategic advantage to dominate its neighbours in Western Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, and thereby fundamentally alter the global balance of power to our disadvantage. 30

From Reagan's assessment of US foreign policy during the Cold War, with its emphasis on the significance of the Eurasian landmass, we can draw some inferences about US policy in the post-Cold War era, albeit with a slight twist. During the Cold War era, it was the USSR that the United States had endeavoured to contain, but now it is China and to a lesser extent Russia. And, once again, the Eurasian landmass is the central focus of US policy-making elites.

The imprint of Mackinder on US foreign policy has also continued in the aftermath of the demise of the geopolitical pivot, the USSR. “Mackinder's ideas influenced the post-Cold War thesis – developed by prominent American political scientist Zbigniew Brzezinski – which called for the maintenance of ‘geopolitical pluralism’ in the post-Soviet space. This concept has served as the corner-stone of both the Clinton and Bush administration's policies towards the newly independent states of Central Eurasia.” 31

Extrapolating from Mackinder's Heartland theory, I consider the Caspian region and its surrounding area to be the Eurasian Heartland. In addition to its widespread and rich energy resources, the region's land-locked central positioning at the crossroads of the energy supply routes in the Eurasian landmass have caused it to receive a lot of attention from scholars and political strategists in recent times. Until the dissolution of the USSR in 1991, this region had been closed to interaction with the outside world, and therefore, to external interference. Since then, the huge natural resources of the region have opened it up to the influence of foreign powers, and the Caspian region has therefore become the focal point of strategic rivalries once again in history. This has led several scholars and journalists to call this struggle to acquire Caspian hydrocarbon resources the ‘New Great Game,’ 32 in reference to the quests of the Russian and British empires for dominance over the region in the nineteenth century.

Without a doubt, the growing global demand for energy has fostered strategic rivalries in the Caspian region. Oil's status as a vital strategic commodity has led various powerful states to use this vital resource and its supply to the world markets as a means to achieve their objectives in global politics. For our purposes, I shall focus on the geo-strategic interest of the United States in the Caspian region.

The United States, which politically controls the Gulf oil to a great extent, is not actually energy-dependent on oil from the Caspian region. Hence, US interests in the Caspian region go beyond the country's domestic energy needs. The political objective of the US government is to prevent energy transport unification among the industrial zones of Japan, Korea, China, Russia, and the EU in the Eurasian landmass and ensure the flow of regional energy resources to US-led international oil markets without any interruptions. A National Security Strategy document in 1998 clearly indicates the significance of regional stability and transportation of its energy resources to international markets. “A stable and prosperous Caucasus and Central Asia will help promote stability and security from the Mediterranean to China and facilitate rapid development and transport to international markets of the large Caspian oil and gas resources, with substantial U.S. commercial participation.” 33

In line with the acknowledgement of the increasing importance of the Caspian region, Silk Road Strategy Act 34 has put forward the main features of the US's policies towards Central Asia and the Caucasus. As Çağrı Erhan asserts, Silk Road Strategy Act has been grounded on the axis of favouring economic interests of the US and American entrepreneurs and this main line is supplemented with several components such as ensuring democracy and supporting human rights that conform to an American definition of globalisation. 35 As a matter fact, a 1999 National Security Strategy Paper emphasised economic issues and referred to the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Pipeline Project Agreement and Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline Declaration on November 19, 1999.

We are focusing particular attention on investment in Caspian energy resources and their export from the Caucasus region to world markets, thereby expanding and diversifying world energy supplies and promoting prosperity in the region. A stable and prosperous Caucasus and Central Asia will facilitate rapid development and transport to international markets of the large Caspian oil and gas resources, with substantial U.S. commercial participation. 36

In that context, the US finds it necessary to establish control over energy resources and their transportation routes in the Eurasian landmass. Therefore, from the US's point of view, the dependence of the Eurasian industrial economies on the security umbrella provided by the United States should be sustained. To put it clearly, US objectives and policies in the wider Caspian region are part of a larger “grand strategy” to underpin and strengthen its regional hegemony and thereby become the global hegemon in the twenty-first century.

Zbigniew Brzezinski, the former national security advisor to President Jimmy Carter, has repeatedly emphasised the geo-strategic importance of the Eurasia region. He claimed that the United States' primary objective should be the protection of its hegemonic superpower position in the twenty-first century. In order to achieve this goal, the United States must maintain its hegemonic position in the balance of power prevailing in the Eurasia region. He underscored the vital geo-strategic importance of the Eurasian landmass for the United States in his 1997 book entitled, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives:

Eurasia is the world's axial supercontinent. A power that dominated Eurasia would exercise decisive influence over two of the world's three most economically productive regions, Western Europe and East Asia. A glance at the map also suggests that a country dominant in Eurasia would almost automatically control the Middle East and Africa. With Eurasia now serving as the decisive geopolitical chessboard, it no longer suffices to fashion one policy for Europe and another for Asia. What happens with the distribution of power on the Eurasian landmass will be of decisive importance to America's global primacy and historical legacy. 37

Therefore, Brzezinski called for the implementation of a coordinated US drive to dominate both the eastern and western rimlands of Eurasia. Hence, he asserts that American foreign policy should be concerned, first and foremost, with the geo-strategic dimensions of Eurasia and employ its considerable clout and influence in the region. In that regard, Peter Gowan summarises the task of the US grand strategy in the twenty-first century with these words,

US Grand Strategy had the task of achieving nothing less than the shaping of new political and economic arrangements and linkages across the whole Eurasia. The goal was to ensure that every single major political centre in Eurasia understood that its relationship with the United States was more important than its relationship with any other political centre in Eurasia. If that could be achieved, each such centre would be attached separately by a spoke to the American hub: primacy would be secured. 38

In order to accomplish that task, the US has the requirement to politically control Eurasian energy resources, in particular oil.

Since the invention of Large Independent Mobile Machines (LIMMs) such as cars, planes and tractors, they have incrementally begun to shape our lives in many ways. LIMMs enable us to do what we do, they make us have jobs, they make the water flow, and they make supermarkets full of food. To put it simply, LIMMs have become the main elements of international economic activities. “For a society in which LIMMs play a central role no other energy resource is efficient as oil. It is compact and easy to use, in its natural state it is located in highly concentrated reservoirs, and it can be transformed into a usable energy product rapidly, cheaply and safely.” 39 To put it simply, oil is the lifeblood of modern economies and the US relies on the international energy market to ensure its security.

As Amineh and Houweling observe, “Oil and gas are not just commodities traded on international markets. Control over territory and its resources are strategic assets.” 40 This is particularly the case for the Caspian region, which is located at the centre of the Eurasian Heartland, and whose potential hydro-carbon resources has made it a playground for strategic rivalries throughout the twentieth century, and will likely continue to do so in the twenty-first century. As the Washington-based energy consultant, Julia Nanay, has observed, “New oil is being found in Mexico, Venezuela, West Africa and other places, but it isn't getting the same attention, because you don't have these huge strategic rivalries. There is no other place in the world where so many people and countries and companies are competing.” 41

The demise of the USSR marked the emergence of the Caspian region as a new energy producer. Until that time, the importance of the region as an energy source had not been appreciated with the exception of Baku, which enjoyed an oil boom for a few decades in the late nineteenth century. Even though there are disagreements on the extent and quantity of potential energy resources in the region, and thus on its geo-strategic significance, a consensus does exist on the fact that the region's economically feasible resources would make a significant contribution to the amount of energy resources available to world energy markets. The principal reason for this consensus emerges from Kazakhstan's rich oil reserves at the age of volatile high oil prices.

With its geopolitical positioning at the heart of Central Asia, Kazakhstan is one of the largest countries in Eurasia. It is sharing borders with two potential Eurasian great powers Russia and China. Apart from its significant geopolitical location, Kazakhstan has massive untapped oil fields in Kashagan (the largest oil discovery in the past 27 years) and Tengiz (discovered in 1979 to be comparable in size to the former), with its little domestic consumption and growing export capacity. “Its prospects for increasing oil production in the 2010–20 time frame are impressive, given the recognized potential offshore in the North Caspian. Production estimates for 2010 range upward of 1.6 mmbpd, and by 2002 Kazakhstan could be producing 3.6 mmbpd.” 42

Kazakhstan views the development of its hydrocarbon resources as a cornerstone to its economic prosperity. However, Kazakhstan is land-locked. In other words, Kazakhstan cannot ship its oil resources. Therefore, it is required to transport its oil through pipelines, which would cross multiple international boundaries. Thus, “one thing that is now confusing to foreign oil company producers in Kazakhstan is the ultimate US strategy there with regard to exit routes. If the goal is to have multiple pipelines bypassing Russia and Iran, any policy that would encourage additional oil shipments from the Caspian across Russia, beyond what an expanded CPC can carry and existing Transneft option, works against the multi-pipeline strategy and further solidifies Kazakh-Russia dependence.” 43 In addition to Russia, China also considers Kazakh oil resources as vital to its energy security as elaborated below.

“Therefore, the countries of Central Asian region represent a chess board, harkening back to Brzezinski's imagery, where geopolitical games are conducted by great powers, mainly the United States, Russia, and China. And Kazakhstan is at the center of this game.” 44 Hence, Kazakhstan has become the focal point of strategic rivalries in twenty-first century.

Since Kazakhstan's untapped oil reserves at the Eurasian Heartland have great potential to underpin stability of US controlled international energy market, these resources play a viable role for the US grand strategy. For the stability of a worldwide market space, Kazakh oil development and its flow to the international energy market, just like Iraqi oil, plays a viable role. In that regard, it is not a surprise to acknowledge that George W. Bush created the National Energy Policy Development Group (NEPD) commonly known as the Cheney Energy Task Force's report on May 2001, 45 which recommends initiatives that would pave the way for Kazak oil development. US Senator Conrad Burns indicates, “Kazakh oil can save the United States from energy crisis” and avert the US's long dependence on Middle East oil. 46 He also argues that Caspian oil could be very important both for strengthening world energy stability and providing international security by noting the importance of the Baku-Ceyhan pipeline project for the export of Kazakh oil. Hence, Kazakhstan could become a major supplier of oil in the international energy market, whereby it would alleviate the disastrous consequences of coming global peak oil to the US.

The non-OPEC character of Kazakh oil is also a fringe benefit to the US`s interests in diversifying the world`s supply of oil in order to underpin stability of its internal oil market. “Non-OPEC supplies serve as a market baseload, consistently delivering the full level of production of which those resources are capable. Clearly, diversifying and increasing these non-OPEC sources provides a more secure core of supplies for the United States and other consumers to rely upon.” 47 Thus, “the question is not OPEC versus non-OPEC. Rather, the issue to address is how to continue encouraging non-OPEC supply growth and diversity, preferably with the involvement of international oil companies (or IOCs, including US oil companies).” 48 Hence, non-OPEC Kazakh oil development and its secure flow to Western markets would enhance stability of the international energy market.

One should also note that US interests in Kazakh oil development and this secure export is not restricted to oil. It also provides political leverage to the US in the Eurasian landmass. The flow of landlocked Kazakh oil to the international energy market though BTC would not only bypass Russia and Iran`s influence in the region, but also shift Kazakhstan's security orientation towards the US and would open the channels of cooperation in the war on terror. Thus, joining Kazakh wide, rich oil reserves to the BTC will accelerate this pipelines' geo-strategic importance. Hence, BTC`s fringe benefit to the US will be “to project power into the Caspian/Central Asian arena in order to check Russian, Chinese and Islamist influences (Iran in particular).” 49

In that regard, rivalry over regional energy resources and their export routes are only a part of a multi-dimensional strategic game to politically control the Eurasian landmass. “Although new strategic developments might determine the choice, but the export options for Caspian oil in 2020 remain the same: the old North to Russia, South to Iran, West to South Caucasus and Turkey, East to China, or Southeast to India.” 50 For our purposes, we will analyse Russian, Chinese and European interests in Caspian hydrocarbon resources.

RUSSIA

Russia has been playing an important role in the Caspian region. It has a significant influence in the region as the largest trading partner for each newly independent state, and the principal export route for regional energy resources. Thus, analysis of Caspian energy and its development should take Russian policy dimension into consideration.

“Russian policy toward the development of the energy resources of the Caspian Basin is a complex subject for analysis because it nests within several broader sets of policy concerns.” 51 These policy concerns could be classified under three dimensions: First, Russia's relations with the US, which has been actively pursuing its interests in the region. Second, Russia's relations with former Soviet states or its so-called ‘near abroad’. Third, Russian policy toward its own domestic sector should be considered.

Before analysing Russian policy on Caspian energy resources, one should take a closer look at her monopoly over existing pipeline routes. Russia had provided the only transportation link through Baku-Novorossiysk pipeline and most of the rail transportation from the region until the opening of an ‘early oil’ pipeline from Baku, Azerbaijan to Supsa, Georgia in April 1999. Currently, the Russian route is the most viable option for Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to export their oil reserves to the world markets. With the completion of the Chechen bypass pipeline, Azerbaijan commenced exporting its oil reserves through Russian territory in the second half of 2000. Moreover, completion of the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) pipeline has led to the flow of Kazakh oil exports from the Tengiz oilfield to the Russian Black Sea port of Novorossiysk. Russia has been developing its own oil fields and expanding its existing pipeline system in the Caspian region. State owned oil company Lukoil, gas company Gazprom, and pipeline network operator Transneft were the principal tools at the hands of Russian diplomats. In June 2002, conclusion of a wide range of agreements with Kazakhstan marked a decisive victory for Russia over Kazak oil export channels. As indicated below, this set of agreements also opened the way for Kazakhstan to link its oil resources to the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline. Meanwhile, Russians have been looking for ways to increase their Caspian oil exports. In that regard, Moscow has ambitious plans to increase the total capacity of its pipeline network around the Caspian.

To make it straight, Moscow considers maintaining its monopoly over the flow of Caspian energy resources would lead Russia not only to gain political leverage over European countries with ever-increasing energy needs, but also regain its political dominance over the newly independent countries. In that regard, not only American physical presence but also US-origin oil companies' investments at the ‘back garden’ of Russia are perceived as a vital threat to Russian national security. This is simply the case for the US-sponsored Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline project. “The Russian government has always understood that this pipeline was part of the broader US strategy to cut all links with Moscow among the former Soviet states in the Caucasus, building a new economic infrastructure that would dissuade the Caucasus group from ever renewing these ties.” 52

Moscow anticipates that sooner or later the US will project Turkey as a regional energy hub for the export of hydrocarbon resources of the Middle East and Central Asia to Europe. Therefore, the US has supported an East-West energy corridor and pushed forward several pipeline projects bypassing Russia such as BTC, BTE, and NABUCCO. Moscow perceives the US's insistence on an East-West energy corridor as a strategy to isolate Russia strategically from the EU. At the end of the day, Russia graphed its famous energy weapon and developed an energy strategy to break this process. Thus, Russia has been pushing ahead the trans-Balkan project known as the Burgas-Alexandroupolis oil pipeline. The pipeline will be 280 kilometres long and carry oil from the Bulgarian port of Burgas on the Black Sea to Greece's Alexandroupolis on the Aegean. The $1 billion project has significant geo-political implications that go beyond exporting Caspian region hydrocarbon resources to Europe. First, the Russian project will undermine the US attempt to dictate the primacy of the BTC as the main Caspian export pipeline to Western markets. Second, Russia considers the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline as an extension of the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) that already connects the oilfields in western Kazakhstan with the oil terminal at Novorossiisk . Thus, Kazakhstan will continue to depend on Russia to export the bulk of its oil to the Western market, even if BTC will be linked to Astana. Finally, the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline will lessen the amount of Caspian oil required to be exported through the Odessa-Brody pipeline in Ukraine. Through the Odessa-Brody pipeline, Poland and Ukraine had been expecting to have direct access to the Caspian oil reserves; however, it looks like their hopes to bypass Russia will not be realised. Thus, Moscow has revealed to Washington that it will not let Ukraine gravitate towards the US orbit.

According to M. K. Bhadrakumar, former Indian ambassador to Turkey, “A spectacular chapter in the Great Game seems to be nearing its epitaph.”53 In that regard, Russia's influence over Kazakhstan has been enhanced with the signing of the Burgas-Alexandroupolis pipeline project on March 15, 2007 contrary to Western media reports speculating on Russia's declining influence on Kazakhstan.

Besides its pipeline initiatives, Russia prefers to play a zero-sum game through its national oil companies (NOCs) to produce Caspian hydrocarbon resources. In that regard, the US's initiatives to develop regional resources in a more efficient manner do not attract much attention from Russian diplomats who rely on ‘relative gains’ rather than ‘absolute gains’. 54 In order for cooperation to flourish between them, the US should find a way to convince Moscow that Russian NOCs do not have the technological and financial resources to develop hydrocarbon reserves, whereby Russia will need Western oil companies, preferably American-origin ones, to produce its hydrocarbon reserves. Apart from regional hydrocarbon resource development, the US needs Russian help to foster peace and stability in Eurasia. It looks like a modus vivendi can be reached only if Russia adopts free market principles and considers absolute rather than relative gains . However, there are no clear signals in that respect.

CHINA

China has incrementally given the Caspian region increasing geo-strategic importance since the end of the Cold War. According to Guo Xuetang, “As the US established a military presence in Central Asia and the United States carried out preventive military activities against China in East and South Asia by strengthening the US-Japan alliance, deploying more strategic submarines and other deterrent weapons, and ingratiating with the Indians to counterbalance China's rising power, China's leadership has faced tougher geopolitical competition over Central Asia.” 55

Since the mid-1990s, energy security has gradually become an important concern for China as domestic energy supplies have failed to meet domestic demand. China is the third largest coal producer and second largest consumer in the world. Thus, this shortfall arises from a shortage of energy in the forms required. Dramatic growth of the use of road transport in China has also accelerated the demand for oil products. Therefore, domestic oil production has failed to keep pace with the demand, whereby China became dependent on imported oil in 1995. With this trend of growing oil demand, domestic production will soon reach its peak point. Apparently, energy supply security, and the availability of oil in particular, has become an increasingly urgent concern for the ruling Chinese Communist Party. Despite the fact that there are several interrelated and independent variables to calculate China's future oil demands, “a consensus seems to exist that annual demand is likely to rise from a present level of around 230 million tonnes to 300 million tonnes by 2010 and at least 400 million tonnes by 2020, though unexpectedly low rates of economic growth would reduce demand to below these levels. Over this period China's share of world oil consumption will probably rise from its current level of about 6% to as high as 8–10%.” 56

Hence, China has been looking for ways to build pipeline routes to export Caspian oil reserves eastwards while the United States has been looking to export Caspian energy westwards. Dekmeijan and Simonian have observed that “as an emerging superpower with a rapidly expanding economy, China constitutes one of the potentially most important actors in Caspian affairs.” 57Its rapidly increasing energy demands and declining domestic energy supplies indicate that China is increasingly becoming dependent on energy imports. According to Dru C. Gladney, “Since 1993, China's own domestic energy supplies have become insufficient for supporting modernization, increasing its reliance upon foreign trading partners to enhance its economic and energy security leading toward the need to build what Chinese officials have described as a ‘strategic oil-supply security system’ through increased bilateral trade agreements.” 58 In that regard, China, as the second largest oil consumer after the United States, has defined its energy security policy objectives in a manner “to maximise domestic output of oil and gas; to diversify the sources of oil purchased through the international markets; to invest in overseas oil and gas resources through the Chinese national petroleum companies, focusing on Asia and the Middle East; and to construct the infrastructure to bring this oil and gas to market.” 59

For our purposes, China's objective to diversify the sources of imported oil from the Caspian region plays a vital role. As Speed, Liao, and Dannreuther have observed, “Since the mid-1990s official and academic documents in China have proclaimed the virtues of China's petroleum companies investing in overseas oil exploration and production in order to secure supplies of Chinese crude oil, which could then be refined in China.” 60 In that regard, China has begun to make generous commitments, the largest of which were in Kazakhstan. According to these scholars, “At the heart of this strategy lies the recognition that China is surrounded by a belt of untapped oil and gas reserves in Russia, Central Asia and the Middle East.” 61 In the Kazakh region, there is high potential for further hydrocarbon discoveries.

The target for China's oil industry is to secure supplies of 50 million tonnes per year from overseas production by 2010. The fulfilment of this objective is directly related to China's involvement in strategic rivalries over the Caspian basin energy resources. Due to the emergence of Japan as a competitor for Russian hydrocarbon resources and Russia's indecisiveness about the Siberian pipeline, which would export high amounts of Russian crude oil to China, former Soviet members, in particular Kazakhstan, have emerged as more viable options. 62

China made generous commitments through its state-owned oil company, CNPC, to actualise the West-East energy corridor. This is particularly the case for the commitments made in Kazakhstan to develop two oilfields in Aktunbinsk and an oil field in Uzen. One should note that this pipeline has crucial political dimensions that supersede the significance of its commercial returns. As William Engdahl indicates, “the pipeline will undercut the geopolitical significance of the Washington-backed Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline which opened amid big fanfare and support of Washington.” 63 Thus, it would be plausible to assert that, to use a similar phrase to the one of Mackinder's, who controls the export routes, controls the energy resources, who controls the energy resources, controls the Eurasian Heartland. However, these arguments are valid only to a certain extent.

One should also note that, as Dru C. Gladney has stated, “the pipeline is important for the United States but hardly a vital concern… . The United States is interested in the stability and economic development of the region and in ensuring that a mutually beneficial relationship is established with the Central Asian republics. Because the Central Asian region of the CIS shares borders with China, Russia, and Iran, these newly independent states are important to the United States with or without oil.” 64 Another point that should be kept in mind is that “alternate sources of hydrocarbons for China would mean decreasing reliance on the Middle East as a sole source, thus decreasing competition in the region and the potential for tensions in the Persian Gulf.” 65 One should be clear on the point that so far as pipeline initiatives would promote the establishment of free-market democracies, the United States would welcome them on the condition that the oil flow would not be in substantial amounts. Gladney concludes, “In this regard, a pipeline to China could help to bring Kazakhstan into the global economy, as well as to wean it from sole dependence on Russia.”66 Hence, it will contribute to the US grand strategy in the twenty-first century.

CONCLUSION

From an offensive realist perspective, I have argued that the principal objective of US grand strategy in the twenty-first century is global hegemony. I have underlined that a true grand strategy is a combination of wartime and peacetime strategies, therefore, I asserted that American wartime (the US-led wars in Afghanistan, and Iraq) and peacetime (political support for the costly BTC pipeline project) strategies all serve the US grand strategy in the twenty-first century. I have also argued that the region surrounding the Caspian basin plays a vital role the US grand strategy. In that regard, I preferred to call that area, to use term of Sir Halford Mackinder, the Eurasian Heartland. I have demonstrated that this area has significant untapped non-OPEC oil reserves, particularly in Kazakhstan, that will underpin stability of US-controlled international oil markets. Interests and policies of Russia and China, two main Eurasian challengers of US grand strategy in the twenty-first century, are also analysed. It is concluded by noting that as long as the Caspian region's untapped oil reserves are developed in a manner contributing to regional stability and economic development, there is not much cause for concern over the success of the US grand strategy in the Eurasian Heartland.

Nevertheless, one should bear in mind that unless the US finds a way to stabilise international oil markets and decrease the price of oil, the success of the US grand strategy in the twenty-first century is dubious. Volatile high oil prices not only hurt the proper functioning of US-controlled international economic structure, but also make it more difficult for the US to manipulate oil producers (i.e., Russia and Iran) and consumers (i.e., China and India) in order to serve its grand strategy.

READ FROM TOP.

PUT A STOP TO THE EMPIRE MADNESS. IT'S NOT GOING TO END WELL FOR ALL OF US.....

SEE ALSO:

bullshit from NATO, londoncrap and little zelenshittt-t…..FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....