Search

Recent comments

- economy 101....

5 hours 44 min ago - peace....

6 hours 33 min ago - making sense....

9 hours 11 min ago - balls....

9 hours 14 min ago - university semites....

10 hours 3 min ago - by the balls....

10 hours 17 min ago - furphy....

15 hours 32 min ago - nothing new....

16 hours 4 min ago - blood brothers....

17 hours 1 min ago - germanic merde....

17 hours 5 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

summers of discontent…...

LONDON, June 21 (Reuters) - Tens of thousands of workers walked out on the first day of Britain's biggest rail strike in 30 years on Tuesday, with millions of passengers facing days of chaos as both the unions and government vowed to stick to their guns in a row over pay.

The strike by more than 40,000 rail staff, which is due to be replicated on Thursday and Saturday, caused major disruption across the network, bringing most services to a standstill and leaving major stations deserted. The London Underground metro was also mostly closed due to a separate strike.

READ MORE:

https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/biggest-rail-strike-30-years-brings-uk-standstill-2022-06-21/

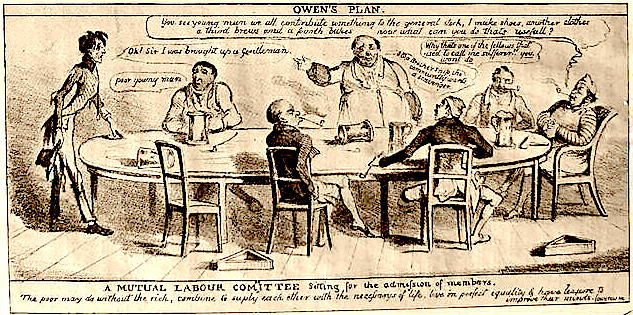

REMEMBERING THE GNCTU.....

The Grand National Consolidated Trades Union of 1834 was an early attempt to form a national union confederation in the United Kingdom.[1]

There had been several attempts to form national general unions in the 1820s, culminating with the National Association for the Protection of Labour, established in 1830. However, this had soon failed, and by the early 1830s the most influential labour organization was the Operative Builders' Union.[2]

In 1833, Robert Owen returned from the United States, and declared the need for a guild-based system of co-operative production. He was able to gain the support of the Builders' Union, which called for a Grand National Guild to take over the entire building trade.[2] In February 1834, a conference was held in London which founded the Grand National Consolidated Trades Union.[3]

The new body, unlike other organisations founded by Owen, was open only to trade unionists and, as a result, initially Owen did not join it.[2] Its foundation coincided with a period of industrial unrest, and strikes broke out in Derby, Leeds and Oldham. These were discouraged by the new union, which unsuccessfully tried to persuade workers to adopt co-operative solutions.[3] Six labourers in Tolpuddle, Dorset, attempted to found a friendly society and to seek to affiliate with the Grand National. This was discovered, and in 1834 they were convicted of swearing unlawful oaths, and they were sentenced to transportation for seven years. They became known as the Tolpuddle Martyrs and there was a large and successful campaign led by William Lovett to reduce their sentence.[2] They were issued with a free pardon in March 1836.

The organisation was riven by disagreement over the approach to take, given that many strikes had been lost, the Tolpuddle case had discouraged workers from joining unions, and several new unions had collapsed.[3] The initial reaction was to rename itself the British and Foreign Consolidated Association of Industry, Humanity and Knowledge, focus increasingly on common interests of workers and employers, and attempt to regain prestige by appointing Owen as Grand Master.[4] The organisation began to break up in the summer of 1834[5] and by November,[6] it had ceased to function:[3] Owen called a congress in London which reconstituted[7] it as the Friendly Association of the Unionists of All Classes of All Nations[8] with himself as Grand Master,[5][9] but it was defunct by the end of 1834.[7] Meanwhile, the Builders' Union broke up into smaller trade-based unions.[2]

Owen persevered, holding a congress on 1 May 1835 to constitute a new Association of All Classes of All Nations,[10] with himself as Preliminary Father.[11] This was essentially a propaganda organisation, with little popular support, which attempted to gain the ear of influential individuals to propose a more rational society. In 1837, it registered as a friendly society, but was initially overshadowed by Owen's similar National Community Friendly Society.[8] In 1838, it was able to expand significantly by sending out "social missionaries", setting up fifty branches, most in Cheshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire.[12] In 1839, the National Community and the Association of All Classes merged to form the Universal Community Society of Rational Religionists.[13]

Despite its name, the Grand National was never able to gain significant support outside London[14] and, as a result, Lovett's London Working Men's Association was its most important successor.[3] The next attempt to form a national union confederation was the National Association of United Trades for the Protection of Labour.

READ MORE:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grand_National_Consolidated_Trades_Union

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW................

- By Gus Leonisky at 22 Jun 2022 - 7:27am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

troc…….

The Owen plan was to work a system of exchange of goods between workers — that excluded bosses, investors and governments — like I give you two carrots and you give me three potatoes...

remembering 1926......

From part 2 — A SHORT ECONOMIC HISTORY OF BRITAIN — BRITAIN SINCE 1750. Page 190... From Oxford University Press 1965.

Ernest Bevin (9 March 1881 – 14 April 1951) was a British statesman, trade union leader, and Labour politician. He co-founded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union in the years 1922–1940, and served as Minister of Labour and National Service in the war-time coalition government. He succeeded in maximising the British labour supply, for both the armed services and domestic industrial production, with a minimum of strikes and disruption.

His most important role came as Foreign Secretary in the post-war Labour government, 1945–1951. He gained American financial support, strongly opposed communism, and aided in the creation of NATO. Bevin was also instrumental to the founding of the Information Research Department (IRD), a secret propaganda wing of the UK Foreign Office which specialised in disinformation, anti-communism, and pro-colonial propaganda. Bevin's tenure also saw the end of British rule in India and the independence of India and Pakistan, as well as the end of the Mandate of Palestine and the creation of the State of Israel. His biographer Alan Bullock said that Bevin "stands as the last of the line of foreign secretaries in the tradition created by Castlereagh, Canning and Palmerston in the first half of the 19th century".[1]

READ MORE:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernest_Bevin

Note that the King made a public comment about Churchill's provocative announcement....

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..................

capital vs labor…..

As British rail workers continue their strike, Tories are trying to force scabs to replace strikers. They only reason they might be able to get with it: Britain’s many laws that are rigged against workers and organized labor.

As the RMT strike began, and viewers could see for themselves how effective the union has been in mobilizing its members, the government responded with news that it would change the law in order to make it harder for unions to win. At present, it is unlawful for agency employers to supply workers to take over the duties of striking workers. The agencies do not want to be used as strikebreakers, but the government insists that they can and will be.

It is remarkable how easily this government changes the law to help bosses, and yet how hard they find it to change the law to help workers, even where they have promised to do just that. As long ago as December 2019, the government pledged in the Queen’s Speech to introduce a bill which would “enhance workers’ rights, supporting flexible working, extending unpaid carers’ entitlement to leave and ensure workers keep their hard-earned tips.”

The bill was supposed to implement the findings of of the government-commissioned Taylor Report, which held, for example, that agency workers should have the right to request direct employment with their employer. That was never a generous policy; all that workers were promised was a right to ask. Even if it had been granted, employers would still have been free to say that it suited them to keep workers at arms’ length, and to deprive them of their rights. That promise was, however, widely reported in the press, earning the government favorable publicity, and was presented as a pillar of the Conservatives’ plans to “level up” Britain. Two and a half years later, it has been quietly dropped.

The reason why there had been a policy consensus at the top of British society in favor of offering agency workers something is that they are some of the clearest victims of the skewed nature of our employment law, which serves in all sorts of subtle ways to protect the interests of the rich. Up until 2006, it was the understanding of every lawyer in Britain that agency workers were (as their names suggests) “workers” in employment law, meaning that they could claim unpaid wages, etc., from the employer where they worked.

That year, however, the Employment Appeal Tribunal held that agency workers were not in fact workers in the normal sense. It held that agency workers have no rights in relation to businesses where they worked. If the employer does not pay them, they can sue their agency — they cannot sue the business where they are based. If they are unfairly dismissed, they have no rights at all.

It is grotesque that the government should expect agency workers to be used as a stage army to defeat striking workers, and doubly so when we think how the government has promised agency workers merely the weakest of all possible rights and failed to deliver even that.

But this pattern, in which rights are typically promised at exactly the same time that trade unions are attacked, is not a new one. It is in fact typical of how individual employment law has developed in this country, at every point, over the past fifty years.

This process goes back to the very establishment of the Industrial Tribunal (the forerunner of today’s Employment Tribunal). The tribunal was introduced by the Industrial Relations Act 1971, which gave them the power to hear unfair dismissal claims. The act was introduced by the Conservatives, not Labour. It was opposed by the trade unions. It was not passed as a result of workers raising their demands in ever increased volume until the state was obliged to recognize them. Rather, politicians sought to defeat a rising workers’ movement, and use the expansion of the law as one of a package of measures all intended to weaken that cause.

The act was intended to legalize disputes between workers and employers, requiring unions to register, giving registered trade unions and them alone immunity from being sued, and banning unofficial strikes. The act also established a National Industrial Relations Court (NIRC), which was empowered to grant injunctions to prevent strikes.

Opposition to the act motivated unofficial strikes, including those which led five dockworkers to be jailed at Pentonville prison for contempt of court. While the power of tribunals to hear claims of unfair dismissal was a subordinate concern for critics of the act, it was part of the story. As part of its opposition to the act, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) instructed affiliated unions to withdraw their representatives from tribunal panels.

Part of the reason for union hostility to tribunals was the way in which they were promoted as an alternative to strikes. Advocates of trade union power grasped that making the fairness of dismissals a test of legal power would disadvantage workers. Managers had deeper pockets than any union, would be able to afford more expensive representation, and could expect to receive greater respect from the tribunal than any employee ever would.

The period when tribunals grew fastest — between 1980 and 1999 — was a period of neoliberal breakthrough. Government policies to reduce subsidies to the manufacturing industry, relocate employment from northern to southern England, and restructure the economy toward services all made redundancies commonplace.

Tribunals became a popular means to raise employee complaints since the alternative — strikes to prevent dismissals — seemed impossible after the defeat of the steelworkers in 1981 and the miners in 1984–85, and, crucially, as a consequence of anti-union laws which introduced measures like compulsory balloting and which put practical barriers in the way of striking.

Between 1980 and 1993, Conservative governments passed six Acts of Parliament, starting with the Employment Act 1980, to restrict unions’ power to go on strike. Picketing was restricted. Solidarity strikes were outlawed.

The United Kingdom has, in consequence of those laws, the most restrictive anti-union laws in Europe. Under them, the law provides only limited protection for a union against being sued by the employer for breach of contract, and even this protection is heavily circumscribed. The workers involved in industrial action are protected only if the purpose of the strike is industrial and not political, and if the union ballots its members and notifies the employer both in advance of the ballot and afterward of its result.

Workers chose to take their cases to tribunals reluctantly, on the calculation that other and better routes to protect their conditions had been closed. It is possible to measure on a graph of the collapse of days lost to strikes between 1980 and 1999, and to draw alongside it the rise of the number of employment tribunal cases. The two lines intersect in 1989; before that year strikes were more common, and afterward, individual employment claims predominate.

Depressingly, the same pattern continued under a right-wing Labour government from 1997 onward. Despite Labour’s huge majority, and despite the party’s continued dependence on union funds, Tony Blair refused to repeal the Conservatives’ anti-union laws. Almost all the things which socialists find contemptible about contemporary Britain — the ever-accelerating disparity of wealth between rich and poor, the power of the police, the powerlessness inability of protesters to successfully challenge the state — can be traced back to the industrial and political defeats of the 1980s, and our side’s adaptation to our own seeming weakness.

For all these reasons, the importance of this week’s rail strike goes beyond the conflict with the government. What we are seeing is the RMT overstepping the bounds of what has been considered for forty years the absolute limits of what any union can achieve. As an astonishing 89 percent of its members having voted for strike, the union has mobilized and closed the railways. Unsurprisingly, the union’s representatives come across well in interviews; they do so not because they are better briefed than other trade union leaders or wittier (although they are both of those things), but because they have behind them the mandate of the solid support of ordinary rail workers. For decades, British unions have been corrupted by weakness: we are seeing the first hints of the regrowth of collective strength.

This strike opens up the possibility of a different relationship not just been capital and labor but also between protest movements (including but not limited to unions) and the law. After all, if any worker wants to achieve a wage rise that keeps their wages in line with inflation, that cannot be achieved through the law, which offers workers no guarantee of any wage rise, still less one consistent with inflation. And what is true of wages, is true of life, more generally. Movements of the poor and the oppressed win victories because of our ability to mobilize our own numbers, not because the state has any long-term interest in helping us.

READ MORE:

https://jacobin.com/2022/06/britain-anti-trade-union-laws-used-against-strike-rail-workers

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..................