Search

Recent comments

- god's murders....

2 hours 28 min ago - the cliff.....

2 hours 42 min ago - qui bono?

3 hours 56 min ago - envious....

6 hours 18 min ago - crimea...

8 hours 25 min ago - bombing liberation....

9 hours 10 min ago - refrain....

10 hours 36 min ago - trust?....

11 hours 38 min ago - int'l law....

12 hours 4 min ago - more bombs....

21 hours 52 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

it's the planet, stupid…...

In the decade after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the history of Russian and Soviet labor and Social Democracy, once a subject of prodigious academic research, fell into a memory hole, as historians turned toward other topics. An engaged scholar and activist, Eric Blanc has not only revived exploration of a neglected subject but delved deeply into the history of Bolsheviks and Mensheviks and widened his lens to include the too often overlooked revolutionary Marxists of the borderlands of the tsarist empire.

Blanc writes simultaneously sympathetically to the aims and aspirations of the revolutionary socialists but critically as well — which, from a Marxist perspective, following in the tradition of the founder of that approach, ought to be the essential methodology of empirical and theoretical investigations. Revolutionary socialist movements were powerful, even dominant, emancipatory efforts in the non-Russian peripheries. In Georgia, Finland, Latvia, Poland, and elsewhere, they were the national liberation movements of the first two decades of the twentieth century.

As a historical sociologist, Blanc uses the natural experiment provided by the diversity of the tsarist political structure — in which the autonomy of the Grand Duchy of Finland allowed a legal labor movement and elections, a situation starkly different from the repression of independent politics in the rest of the empire — to argue that “successful insurrectionary movements [like the Bolsheviks] generally only arise under conditions of authoritarianism,” while “anti-capitalist rupture under parliamentary conditions [as in Finland] requires the prior election of a workers’ party to the state’s democratic institutions.”

He then contends that the usual view that parliamentarianism inevitably leads to socialist moderation is belied by the experience of the Finnish Social Democrats, who became more militant after the revolution of 1905. His book thus advances beyond the usual Russocentrism and credence in Bolshevik exceptionalism evident in much of earlier scholarship and uses the comparative cases of borderland socialists to explain strategic choices, as well as victory and defeat in insurrectionary moments.

Superbly equipped with linguistic skills in eight languages and dedicated to reading in archival and published sources, Blanc brings a passion and energy that enables him to mine diligently the documentary evidence for his exhaustive exploration of the prerevolutionary workers’ movements in Russia. In line with work by Lars Lih and Erik van Ree, he connects the politics of Tsarist Russia’s Social Democrats to Karl Kautsky, who he claims has been caricatured in Western liberal, and even Marxist, accounts as a reformist rather than revolutionary.

Kautsky’s commentary on the Erfurt Program was a foundational text, the window into Marxism for Latvian, Ukrainian, Jewish, and other young activists. In parliamentary regimes, socialists could exploit the opportunity to build a mass workers’ party and work through available institutions and, as occurred in Germany, win large representations, even a majority, in the legislature in order to be ready for the revolutionary rupture with capitalism.

Such a road to power did not exist in Russia proper. But it did in Finland, where the Social Democrats implemented Kautsky’s strategy. As Blanc puts it, “Both Kautsky and his peers under Tsarism insisted that Marxism was a method, not a dogma; tactics and strategy, therefore, always had to be based on a hard-nosed appraisal of a concrete situation.” Until the German Social Democrat appeared to take an equivocal position on his country’s entry into the Great War, Vladimir Lenin considered Kautsky the epitome of Marxist orthodoxy, after which he referred to him as a “renegade” who once had been a Marxist.

Basing his analysis in the social context of late tsarism rather than giving us a simple intellectual history, Blanc contends that it was not Kautsky’s moderation but the entrenched bureaucracy of the SPD that determined its accommodation to the imperial regime in Germany. In Russia, on the other hand, instead of the integrative pressures of bourgeois democracy to work with liberals and the middle classes, autocracy’s erasure of alternative political possibilities and the absence of political outlets and solidified labor organizations led socialist parties to adopt intransigent positions in relation to the regime. There was no other game in town. “At the turn of the century, political nationalism was extremely weak, Russian populism [peasant-oriented socialism] had virtually collapsed, and strong liberal-democratic currents were absent,” he writes.

While Bolsheviks maintained their antipathy to collaborating with the liberals, Mensheviks, Georgian and Ukrainian SDs, and more moderate Marxists after the failure of the 1905 revolution sought alliances with liberals and even, in some cases, with nationalists. This was the great strategic divide that would lead into the final fatal schism in 1917.

Borderland SocialismThe Finnish Social Democrats were in a unique position, given Finland’s autonomy within the empire and the relative freedom that they enjoyed. The Finnish Marxists had their share of conciliationists and intransigents but generally tended toward party unity rather than schism and often sought cooperation with other parties within Finland. Blanc maintains that after 1905, the party grew more militant.

While that is certainly true of important elements within Finnish Social Democracy, most historians of the movement, and Blanc’s own evidence, demonstrate that relative moderation characterized the party well into 1917. This posture conforms with Blanc’s principal argument that where parliamentarianism was possible, socialist parties tended to be more moderate, while in states where such institutions and possibilities for open organization did not exist, as in Russia proper, socialist parties were more militantly revolutionary. In my view, he overestimates the radicalism of the Finnish Social Democrats, who were deeply divided right up to their fateful (and fatal) decision in January 1918 to make an armed bid for power.

The first Marxist party in the empire, founded in 1882, was the Polish “Proletariat” Party, about which Norman Naimark produced a groundbreaking and comprehensive monographin 1979. Jewish parties organized before the Russian and most others, and by 1905 significant Marxist parties worked among Latvians, Finns, Georgians, Ukrainians, Poles, Lithuanians, and others. Muslims were late comers but joined other parties or set up committees and organizations like Hummet, founded by Caucasian Muslims.

The non-Russian parties, like Rosa Luxemburg’s Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPIL) and the Jewish Bund, were critical of Lenin’s notion of a centralized political party, and most non-Russian socialists did not accept his idea of a postrevolutionary Russian state with only regional rather than national cultural autonomy. Except for the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) of Józef Piłsudski and a few small parties, they were not for separation from Russia but wanted a federal structure that recognized ethnic nationality.

Only in January 1918, at a moment when Russia was splintering into separatist states, did Lenin come around and accept both territorial national cultural autonomy and federalism as the basis for the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) and, later, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Still, Bolsheviks were attractive to radical non-Russians, given Lenin’s uncompromising support for national self-determination to the point of separation and his party’s stance in 1917 as “the empire-wide political current most supportive of the demands of dominated national groups.”

Proletarian HegemonyBlanc’s touchstone for understanding revolutionary social democracy in Russia is the evolving strategy of proletarian hegemony — that is, the argument that, in the absence of a powerful liberal bourgeoisie in Tsarist Russia, the working class would have to exercise leadership in the expected bourgeois democratic revolution. This strategy was accepted by almost all Marxist leaders in Russia up to the winter of 1905, when the defeat of the December insurrection in Moscow led Mensheviks and others to contend that militance had led to the defection of the bourgeois liberals and that Social Democrats must moderate their tactics and seek an alliance with them.

Blanc shows that not only the Russian but the Georgian Mensheviks, along with the Jewish Bund, the PPS-Revolutionary Faction, the Ukrainian USDRP, to an extent, and other peripheral parties adopted this more moderate stance — to the chagrin of Lenin, who was appalled by class collaboration and banked on the peasantry instead of the bourgeoisie. The Bolsheviks were joined in their stance by the Latvian Social Democratic Workers’ Party (LSDSP), the SDKPIL, the PPS-Left, and many of the Finnish Social Democrats.

A distinction between the practice of historical sociologists and that of some overly empirical historians appears to be that the former tends to see the forest while the latter often gets lost in the trees. But heeding Marx’s formulation of the agency versus structure problem — “Men make their own history, but they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past” — Blanc’s analyses combine both structural and actor-centered factors.

“The divergent trajectories of socialist organizations across the empire after 1905,” he writes, “are hard to explain without taking into account the political choices made by party leaders, especially following the first Russian Revolution’s defeat.” Once those choices of strategy were made, however, they remained in place well into the next revolution and determined which side of the barricades a party would find itself during and after October 1917. As Blanc even more pointedly asserts:

The result of the revolutionary struggle was by no means preordained by the social structure. Deep social crisis, state collapse, and labour insurgency were necessary but insufficient conditions for anti-capitalist rupture in imperial Russia. At least one other factor was needed: socialist parties that were sufficiently influential, radical, and tactically flexible to help the working-class majority effectively unite to break with capitalist rule.

READ MORE:

https://jacobin.com/2022/06/eric-blanc-revolutionary-social-democracy-russia-finland

SEE ALSO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-LgswD4QveU

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW #########################

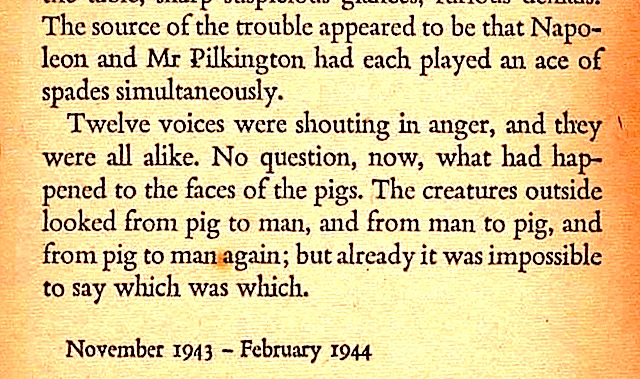

Picture at top: the last paragraph of ANIMAL FARM, by George Orwell.....

- By Gus Leonisky at 23 Jun 2022 - 6:35am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

not new, but worth revisiting…..

BY PAUL FRIJTERS, GIGI FOSTER, MICHAEL BAKERFor more than two years, the world has been swept up in covid mania. Ordinary people of almost every nationality have accepted the covid ‘story’, applauding as strong men and women have assumed dictatorial powers, suspended normal human rights and political processes, pretended that covid deaths were the only ones that mattered, closed schools, closed businesses, prevented people from earning livelihoods, and caused mass misery, poverty, and starvation.

The more these strong men and women did these things, the louder the applause, and the greater the disapprobation and abuse levelled at those who decried such actions. Police bullying of those speaking out against the covid story was cheered on by populations keen to see the naysayers brought to justice.

The past two years have proved that the Germans of the National Socialist period were really nothing special.

Lest we forgetThe West refused to learn, or by now has forgotten, the central lesson of the Nazi period (1930-1945) despite the plethora of eyewitness voices in post-WWII art and science that made it abundantly clear what had happened – from Hannah Arendt to the Milgram experiments to the fabulous play, ‘Rhinoceros’. The key point made by the top intellectuals writing about the Nazi period was that anyone could become a Nazi: there was absolutely nothing odd about the Germans who became Nazis.

They did not become Nazis because their mothers did not love them enough, or because they had rejected God in their life, or because of something inherent in German culture. They simply got seduced by a story and swept off their feet and out of their minds by the herd, making up their reasons as they went along. The brutal lesson that the intellectuals of that era wanted to pass on was that pretty much everyone would have done the same under the circumstances. Evil, in a word, is banal.

READ MORE:

https://brownstone.org/articles/we-can-all-be-evil-and-the-germans-were-nothing-special/

READ FROM TOP.

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW. KEEPING ASSANGE IN PRISON IS EVIL............