Search

Recent comments

- MbS's trap....

3 hours 19 min ago - mooning.....

8 hours 23 min ago - EU gas storage....

12 hours 20 min ago - wrong trousers....

12 hours 32 min ago - failure.....

12 hours 52 min ago - remembering....

14 hours 46 min ago - wrong target....

1 day 4 min ago - aerosols....

1 day 23 min ago - middle powers....

1 day 44 min ago - disgraceful....

1 day 1 hour ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

fear in the backwater of downunder…….

An early Australian leader said: “the doctrine of the equality of man was never intended to apply to the equality of the Englishman and the Chinaman”.

Inter-group violence and “yellow peril” fears were a key factor motivating the setting up of Australia’s political map.

Fear of China is still so entrenched that it’s no surprise that many Australians today carry the absurd fear that an invasion of their country is imminent.

BY Laurie Pearcey

“AUSTRALIA HAS NOT CHANGED – China has changed.” That is a phrase often used by Australia’s new prime minister Anthony Albanese (left) to describe the structural deterioration in relations between Canberra and Beijing. It is not often I agree with an Australian prime minister these days, but in this case, Albanese is bang on the money.

China has indeed changed – it has eradicated absolute poverty, presided over the single largest leap in economic mobility in human history, and enters the next quarter of this century as the world’s second largest economy, arguably destined to overtake the United States as the planet’s largest before too long.

Australia on the other hand, has not changed at all. According to a poll released by the Australia Institute this week, a staggering 10 percent, or 2.5 million Australians, believe China will launch an armed attack on Australia “soon”. This is double the number of Taiwanese who believe Beijing will strike the renegade Chinese province despite the island being recently surrounded by People’s Liberation Army wargames and Taiwanese residents seeing missiles literally flying over their skies after US Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s provocative visit to Taipei earlier this month.

So, what is behind Australia’s fear of an imminent Beijing attack on the great southern land? Is it anxiety produced by a more belligerent Chinese foreign policy and defence posture? Is it down to growing strategic rivalry in the Asia-Pacific? Or is it attributable to something more entrenched in the island nation’s psyche?

Answer lies in history

The answer is intriguing and spans nearly two centuries of Australia’s history, and the very foundation and establishment of our definition of the modern Australian nation.

In 1901, the six colonies of New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Tasmania, South Australia and Western Australia came together as a federation and established the Commonwealth of Australia.

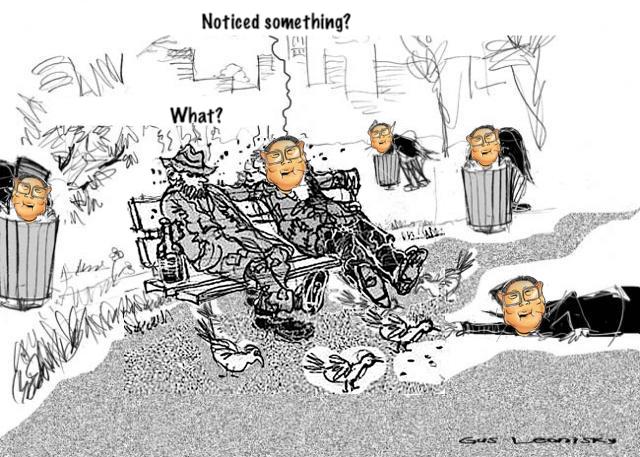

Political cartoons from the period leading up to Australia’s federation portray an evil Chinese invader preparing to take the British colony by force. In one particularly iconic, yet disturbing example, China is depicted as an overweight, bucktoothed menacing mandarin sporting a Qing Dynasty era queue creeping up on Australia’s colonies who are portrayed as young women with snow white skin. Our heroines are seen bravely fending off the frightening Chinese invader with a big stick emblazoned with the word “FEDERATION”.

The federation era saw a proliferation of xenophobic Australian literature with titles such as The Yellow Wave: A Romance of the Asiatic Invasion of Australia, The Coloured Conquest and The Awakening to China appearing on bookshelves Down Under.

Anti-Chinese Riots

Violent anti-Chinese riots appeared in Australia in the second half of the 19th century. By the mid-1850s, there were reportedly 17,000 Chinese working on Australia’s goldmines. Riots were reported as early as 1854, and a particularly nasty one was reported in 1861 when a brass band playing Rule Britannia provided the soundtrack to a few thousand white miners who attacked and set fire to a Chinese camp site and injured more than 500.

Anti-Chinese aggression from these miners was a key ingredient in the formation of the Australian labour movement, which itself is the ancestral forebear of Albanese’s Australian Labor Party.

A version of the famed Eureka Flag painted with the words “No Chinese” was used with a mob of more than 2,000 men who brutally attacked 2,000 Chinese miners. The main Eureka Flag is still trotted out at union rallies in Australia with its depiction of the Southern Cross synonymous with the nation’s labour movement.

White Australia Policy

The first Australian government elected as part of federation was led by Protectionist Party leader Edmund Barton with the support of the Australian Labor Party, and the new government moved decisively to appease the labour movement and cement the young nation’s resistance to the yellow peril.

One of the first acts of parliament passed by the new nation was the Immigration Restriction Act with Hansard records showing the new prime minister saying “the doctrine of the equality of man was never intended to apply to the equality of the Englishman and the Chinaman”.

The new legislation became known as the “White Australia Policy” and restricted immigration to non-whites and was the law of the land until being formally dismantled some seven decades later.

Fear is a national sport

Forget about cricket, this fear of China has almost been a national sport since the formation of modern Australia as we know it. In his seminal work on Australia’s fears first published in 2001, Professor Anthony Burke’s book In Fear of Security: Australia’s Invasion Anxiety contends the nation’s “anxieties about security from the strategic and racial threat posed by Asia” has “permeated the entire society as a powerful form of politics and set of fears”. It has been woven so deeply into the nation’s fabric, that Burke contends “security has been a potent, driving imperative throughout Australian history”.

When you consider this political and societal obsession with a Chinese invasion which has been entrenched since the 1850s, it becomes easier to understand why then defence minister and now opposition leader Peter Dutton asked the nation to not discount the possibility of Australia’s military involvement with a war over Taiwan.

With nearly two centuries of beating the drums about a looming Chinese invasion, is it little wonder so many Australians fear a communist invasion from its north?

No, Prime Minister Albanese – Australia has not changed at all.

Laurie Pearcey is associate vice-president external engagement & outreach at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is a former pro vice-chancellor international at the University of New South Wales and a former chief executive of the Australia China Business Council. The views here are his own.

First published in Fridayeveryday AUGUST 23, 2022

READ MORE:

https://johnmenadue.com/laurie-pearcey-australias-yellow-peril-fear-is-rooted-in-history/

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..........................

- By Gus Leonisky at 31 Aug 2022 - 12:55pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

peace — not war again….

BY CAMERON LECKIEIt is time to take the path less travelled. The Defence Strategic Review must recommend an independent defence and foreign policy if Australia is to successfully navigate the emergence of a multi-polar world.

Through a combination of normal diplomacy and keeping its powder dry the future of the United States imperial system could have been one of almost imperceptible relative decline occurring over many decades. Instead, the maximalist position of the United States with regards to its two main competitors, China and Russia, has precipitated a rapid and ongoing collapse of its power. Whilst the evidence of decline has been mounting for many years, we are now in a period which future historians are likely to describe as the imperial climax of the United States. These same historians will also debate why the United States squandered its standing and position in the world over Ukraine and Taiwan? Entities that by no stretch of the imagination could be justified as being crucial to the security of the United States.

We should be clear what Ukraine and Taiwan represent to the United States imperial system. They represent an anti-Russia and an anti-China located in strategically vital locations. They are bulwarks, with great historic, cultural, economic and security importance to both Russia and China, against which significant leverage can and has been applied by the United States to, as described in the Wolfowitz doctrine, “prevent any hostile power from dominating a region whose resources would, under consolidated control, be sufficient to generate global power.”

The interests of the United States in these two regions has absolutely nothing to do with democracy, support to human rights, sovereignty or whatever the canard of the day is. It is rather more cynical than these lofty ideals. United States Senator Lindsey Graham summed it up recently when he stated:

“I like the path we are on. As long as we help Ukraine with the weapons it needs and economic support, it will fight to the last man.”

For as long as Ukraine and Taiwan can be used to ‘weaken’ Russia or China then the leadership of the United States does not care how many casualties result or how much damage is caused to their economies. The United States’ approach to foreign policy is at this point almost entirely nihilistic. It is focused, like a drowning person, on dragging others down regardless of whether they are an adversary (Russia and China) or an ally (Europe, Taiwan, Australia), in a vain attempt to regain its position as the global hegemon.

This is the background context in which the Defence Strategic Review has been announced.

Given the major changes to the global system currently underway, it is an opportune moment for Australia to conduct such a review. However, euphemisms used by some of the Review’s key players are a cause for concern.

The Defence Minister, Richard Marles, whilst visiting the United States in July stated that the alliance was important to “preserve the rules based global order that underpins our security and prosperity.” As noted by retired Commodore Richard Menhinick several years ago, the ‘rules based global order’ which Australian and allied nations speak of is not the order enshrined in the United Nation Charter. It is rather a euphemism for United States led Western hegemony. A fact which China, Russia and other nations are well aware of.

The second example is a comment by retired Chief of the Defence Force, Angus Houston, where he stated that “the deteriorating strategic environment facing Australia is the worst I have seen in my lifetime.” Whilst many would no doubt agree with Houston, reading between the lines suggests that the actual concern here is that Australia’s security blanket, our alliance with the United States, is no longer fit for purpose.

The concern rising from these statements is that the Review will be used to double down on the status quo, our alliance with the United States, rather than being a first principles consideration of how Australia can best maintain its security and prosperity as the balance of power within the global system continues its realignment from a unipolar to a multipolar system.

This realignment is the core issue of the rapidly changing strategic environment facing Australia. The primary loser in this reordering will be the United States led Western world (i.e. the rules based global order) whose power is and will continue to decline – hence the panic in Western capitals, Canberra included.

The majority of the world’s countries, with the majority of the global population, as well as a large proportion of its economic resources (and potential) are welcoming the emerging multi-polar world order.

The progress of multi-polarity has been grossly under reported in the Western media. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), of which some 139 countries have joined is probably the best known aspect. BRICS is expanding with both Iran and Argentina having submitted membership applications, and Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Egypt intending to follow suit.

The BRICS nations are developing a basket based reserve currency and national digital currencies. China is rapidly developing blockchain technology to support intensified cross-border economic interactions. Major trade deals are occurring via national currencies (e.g. Russia and Turkey, Russia and India, Russia and Iran). These and other financial initiatives will see the United States dollar, the centre of gravity its imperial system, and the Euro becoming increasingly less important in international trade.

Eurasian integration is steadily progressing. The first movement of cargo from Russia to India along the International North South Transportation Corridor (INSTC) being a recent milestone. For those Western strategists who subscribe to Halford Mackinder’s ‘Heartland’ theory, which argues that whoever controls the world island (Eurasia) controls the world, an integrated Eurasia is a nightmare.

The importance of the emerging multi-polar world cannot be overstated. At this stage the momentum of these initiatives is such that it appears highly improbable that it can be stopped. It will be an Asian (or Eurasian) 21st century!

In comparison, what the West has to offer the rest of the world is both insufficient for its development needs and increasingly unattractive, as demonstrated by the perhaps apocryphal story of a Kenyan official, who stated that ‘Every time China visits we get a hospital, every time Britain visits we get a lecture.’ Extra-territorial application of, or threat of, sanctions by the United States are being met with not only condemnation but also having little impact on the willingness of African and Middle East nations to trade and maintain relationships with Russia as highlighted by the warm welcome of its Foreign Minister in recent weeks. It is also increasingly clear that the Western world’s rhetoric about values does not resonate outside of the West. Not surprising given how selectively these values are applied both abroad and at home.

Meanwhile the largely self-inflicted demise of the Western world continues apace. In the UK, former Prime Minister Gordon Brown speaks of childhoods which ‘are starting to resemble shameful scenes from a Dickens novel.’ There are expectations of waves of protest and political dysfunction across Europe as people make the impossible choice between heating and eating and President Macron warns that France is reaching the ‘end of abundance.’

The Defence Strategic Review is occurring at a time when Australia finds itself at a fork in the road. The options are as stark as the potential consequences are serious. Our history, cultural ties and integration into the United States led Western system generates a lot of inertia that make any change from the status quo extremely difficult. Yet maintaining the status quo effectively boxes Australia into a lose – lose – lose situation. A continuing deteriorating relationship with our major trading partner China (where our trade interdependence is growing despite the decoupling rhetoric) as well as increasing isolation from regional countries is the best-case outcome. A best-case outcome that would still be highly detrimental to Australia’s prosperity and at the opportunity cost of dealing with the real existential risks Australia faces related to energy, water, soils, and climate.

And then there is the prospect of war with China – a conflict in which the decision-making centres would be in Washington DC and Beijing, not Canberra. In the unlikely event that the United States and its allies were to ‘win’ it would be a pyrrhic victory that undermines Australia’s prosperity for decades to come. And in the likely event that we lost Australia would have its own century of humiliation to look forward to. There are no good outcomes for Australia from maintaining the status quo, particularly when it is the alliance with the United States that is the greatest single risk factor for a conflict with China.

If maintaining the status quo results in a strategy that is an anachronism of times past that does not offer a viable path for Australia’s security, then there is a clear case for implementing an alternative defence strategy. A strategy which is relevant to the unfolding multi-polar world and the decline of Australia’s traditional and increasingly unreliable security partner and the broader Western world. How could the Review assist in the formulation of an alternative defence strategy?

The starting point must be a realistic appraisal of the threats that Australia faces. Those pushing the China as threat narrative have been very effective in influencing the perceptions of Australians. Many more Australians than Taiwanese think that China will attack Taiwan (or Australia). A result which, according to Allan Behm, shows how ‘popular opinion is detached from geopolitical and geostrategic reality.’ The disproportionate fear of China in Australia, and the resulting China obsession amongst many analysts and commentators, is an outlier in the region. ASEAN nations have a much more nuanced view on China, understanding that they must maintain balanced cooperation with all great powers and not be sucked into the rivalry between the United States and China. This helps to explain why the provocative Pelosi visit to Taiwan garnered little support amongst ASEAN nations. Whilst understanding the risks and concerns the citizens of ASEAN nations assess that the benefits of cooperation with China outweigh the negatives. An assessment that Australia would do well to follow.

The Review can look to other nations for inspiration as to how difficult strategic circumstances can be balanced. We have Singapore, a country which ‘will resolutely refuse to choose sides’ and ‘is not anyone’s vassal state and does not wish harm on any other state.’ We have Papua New Guinea whose foreign policy is based on the principle of ‘friends of all and enemies of none.’ And then we have Vietnam with its ‘three noes’ policy; no military alliances, no aligning with one country against another, and no foreign military bases on Vietnamese soil.

It is ironic that Australia, which is nearly the furthest country from China in our region is also the country that is the most agitated about China’s rise. If Vietnam, with its very difficult historical relationship with China over centuries, can maintain its security without relying upon alliances; there is no feasible reason why Australia, with its comparatively much more favourable circumstances, can not base its defence policy on a similar set of principles.

The Review must recommend that activities that antagonise China, such as air and naval activities in the South China Sea and publishing foreign government funded human rights ‘investigations,’ which have no tangible benefit for Australia be stopped.

Finally, the Review must highlight the awkward fact that the Australian economy would grind to a halt within weeks of a conflict with China as the majority of our liquid fuel supplies pass through the South China Sea. To put it bluntly, Australia is incapable of fighting a war with China and avoiding the complete devastation of our economy.

Which fork will the Review recommend? Whilst taking the path less travelled, an independent defence and foreign policy, may seem daunting it is the path Australia must take. To maintain our alliance with the United States at this stage is leading ourselves down a dead end from which we may never extract ourselves.

READ MORE:

https://johnmenadue.com/the-defence-strategic-review-and-the-decline-of-the-us-led-western-world/

READ FROM TOP.

THE SOLUTION IS SIMPLE. SHOULD CHINA DECIDE TO REUNITE WITH TAIWAN IN WHATEVER WAYS, AND SHOULD THE US DECIDE TO GO TO WAR OVER THIS, WE, AUSTRALIANS, SHOULD PASS THE OPPORTUNITY TO HELP THE USA create more MESS.

WE GOT OUR ARSE KICKED IN VIETNAM, IN AFGHANISTAN, AND POSSIBLY IN OTHER SECRET POOPOOLANDS BY MISUNDERSTANDING THE DYNAMICS OF THE PLACES. IT'S THE SAME WITH "STANDING WITH UKRAINE". STANDING IN SHIT IS NOT THE WAY TO GO. WE HAVE NOT — I MEAN OUR GOVERNMENTS HAVE NOT — UNDERSTOOD THE DYNAMICS OF THE PLACE WHICH IS DIVIDED ACROSS ETHNIC LINES LIKE THE IRISH AND THE UK. STOP SENDING WEAPONS.

SO THERE, BE BRAVE, BOLD AND REALISTIC. SAY NO TO JOINING YET ANOTHER WAR LAUNCHED BY THE USA.

FREEING JULIAN ASSANGE SHOULD BE OUR FIRST PRIORITY.