Search

Recent comments

- dumb blonde....

2 hours 3 min ago - unhealthy USA....

2 hours 36 min ago - it's time....

2 hours 58 min ago - pissing dick....

3 hours 17 min ago - landings.....

3 hours 29 min ago - sicko....

16 hours 17 min ago - brink...

16 hours 33 min ago - gigafactory.....

18 hours 20 min ago - military heat....

19 hours 3 min ago - arseholic....

23 hours 46 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

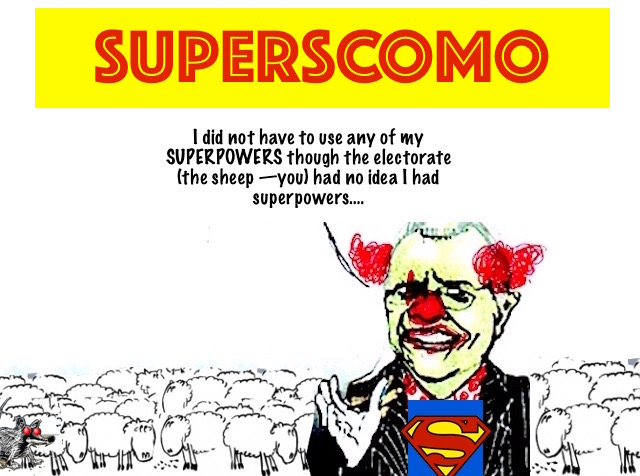

his contempt of public service advice to bypass reality......

Morrison’s self-appointment to six portfolios says a lot about his contempt for the quality and integrity of decision making under his government. The response by PM&C officers, who were in the know, also raises questions about how adequately they exercised their responsibility for good government.

The report by former High Court Judge, Virginia Bell, into Morrison’s self-appointment to administer six departments was released last Friday and was immediately headline news.

A key feature of these appointments was that they were made in secret, not disclosed to the parliament or the public, and in most cases even the responsible minister was not informed.

In brief, Bell found that:

- “The lack of disclosure of the appointments to the public was apt to undermine public confidence in government … and the secrecy with which they had been surrounded was corrosive of trust in government.”

- “There was no delineation of responsibilities between Mr. Morrison and the other minister or ministers appointed to administer the department. In the absence of such delineation, there was a risk of conflict had Mr. Morrison decided to exercise a statutory power inconsistently with exercise of the power by another minister administering the department.”

These findings about the damage Morrison did to accountability and trust in government have received adequate publicity elsewhere. There is, however, another aspect of Morrison’s appointment to administer multiple departments which has received less attention and that is the risks for the integrity of statutory decision making and the quality of government more generally.

Statutory decisions should be evidence-based

Where ministers or officers are granted the power to make decisions as prescribed in the relevant legislation they have a legal responsibility to collect and consider the “evidence or other material to justify the making of the decision”. Equally under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability (PGPA) Act, and its associated rules and directions, the proper and accountable administration of public moneys requires that decisions are based on procedures to ensure:

- Achieving value with the relevant money

- Governance and accountability

- Probity and integrity.

It is difficult to see how a minister can fulfill these requirements for responsible decision making without being briefed by department officials who are expected to have both relevant expertise and best access to the necessary information. If, however, the relevant department officials did not know that Morrison had been appointed as their minister, they could not readily brief him and provide him with the necessary evidence and arguments on which he would then be able to properly base his decision.

But most probably that absence of briefing and information would not have worried Morrison. Indeed, he has been widely quoted for his contempt of public service advice. As Morrison memorably put it, ministers are elected to determine policy, and accordingly he wanted “a public service that is very focussed on implementation”. Equally, the Morrison Government’s administration of grants moneys seriously flouted the provisions of the PGPA Act, and he wasn’t the slightest bit worried.

Quality of government

The chief executive of any large organisation understands (or should understand) that he cannot do everything. The quality of decision making, and the efficiency and effectiveness of the organisation depends upon delegation to sub-ordinates with appropriate lines of accountability.

Those rules apply for a government just as much as for any other large organisation – or even more so, given the number, variety, and complexity of government decisions. That is why we have individual ministers each responsible for one of the main functions of government.

But it is also why the chief executive, or in this case the Prime Minister should never appoint himself as a line Minister. The Prime Minister has enough to do without taking on this additional responsibility which was always intended to be delegated. There is a real risk to the quality of government if, as is likely, the Prime Minister cannot give the time and attention needed to individual ministerial decisions.

In Morrison’s case he has stated that he sought to appoint himself as the minister to some departments because he wanted to be able to influence some particular decisions. However, he could still have sought to have the matter listed for cabinet consideration and had his say there without taking over full responsibility for the decision without any further consultation with the responsible minister.

Rejection of the Petroleum Export Permit 11

In fact, Bell found that Morrison only exercised a statutory power that he enjoyed by reason of his line appointments on one occasion – his decision to refuse the application concerning Petroleum Export Permit 11 (known as PEP-11).

Furthermore, at the initiative of PM&C officers, Morrison was briefed by the responsible department – the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DIESR) before Morrison formally made his decision to reject the PEP-11 application.

Nevertheless, the integrity of this decision-making process is questionable. This is because months before receiving that briefing and making the formal decision, Morrison had publicly made clear his opposition to the PEP-11 application, and had informed Minister Pitt and his department accordingly. Thus, it is questionable what difference the briefing made or how the Prime Minister’s known opposition might even have influenced the briefing.

The role of PM&C

I would contend that senior public servants have a responsibility to warn governments where they think decisions could be against the public interest.

PM&C did brief Morrison that appointing himself to line ministries was “somewhat unusual” – surely an understatement. As already noted PM&C also arranged for DIESR to brief Morrison before he formally took the decision to reject the application for PEP-11.

But in my view, PM&C should have been more on the front foot in pointing out to the Prime Minister the risks to the quality of decision making by substituting himself for the line minister, and the risks to accountability and trust by not announcing these appointments.

For nearly twenty years from 1978 to 1996 I worked closely with Geoff Yeend and Mike Codd when they were consecutively Secretary of PM&C, and I then took over myself from Mike Codd. During all those years I have no doubt that officers in the Government Division of PM&C would have insisted that their views should be conveyed to the Prime Minister as to why these most unusual appointments were not a good idea. Furthermore, if I as Secretary had not supported their message, I think I would have lost their respect and my authority.

The Bell report indicates, however, that the staff from PM&C basically were responding to directives from the Prime Minister’s Office and did what they were told. But even in the case of the contentious PEP-11 decision, the Bell report records that the then Secretary of PM&C “did not seek to speak with Mr. Morrison and to advise him in stronger terms than those used in the brief”, despite the risk of legal challenge.

In addition, Morrison claimed that he thought PM&C had arranged for the announcement of each of his appointments to the line ministries. Bell is sceptical about this claim, but it begs the question of why PM&C did not follow up with the Prime Minister and urge that the appointments be announced, consistent with past practice and good government.

Incidentally, the same point applies to the Governor General who must have been aware of non-announcement and should have asked why. Having worked with two of his predecessors, I am sure they would have.

Conclusion

As Bell found, Morrison’s secret appointment of himself to five other line ministries ignored the need for proper accountability and damaged trust in government. But that is not all. Beyond that there were significant risks to the integrity of the decision making process and the quality of government more generally.

And in that context, PM&C also failed in its duty to adequately warn about the risks these secret appointments posed.

Unfortunately, Morrison’s behaviour as Prime Minister is consistent with an exaggerated sense of entitlement. That by virtue of his election he was entitled to do what he liked and to ignore the checks and balances normally associated with a well-functioning democracy.

READ MORE:

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW.............

- By Gus Leonisky at 30 Nov 2022 - 5:02am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

AT LAST!......