Search

Recent comments

- destabilising....

41 min 40 sec ago - lowe blow....

1 hour 13 min ago - names....

1 hour 50 min ago - sad sy....

2 hours 15 min ago - terrible pollies....

2 hours 25 min ago - illegal....

3 hours 37 min ago - sinister....

5 hours 59 min ago - war council.....

15 hours 44 min ago - flying saucers....

15 hours 55 min ago - casualties....

16 hours 7 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

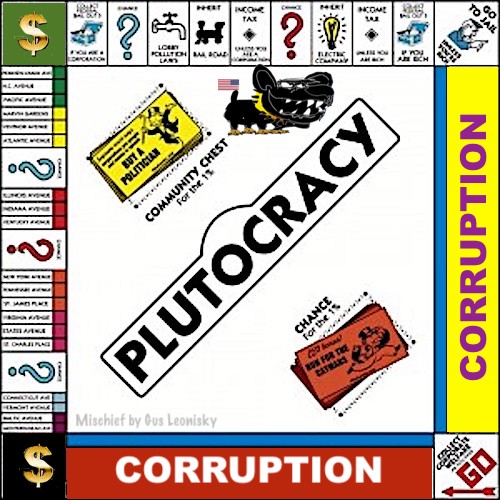

we get the crumbs on the floor just before the one per cent cleans up....

Since the global financial crisis, big banks have taken a backseat, and asset managers have become the – often self-appointed – new experts and administrators of capitalism. Yet, collectively they also own global housing and infrastructure assets, prioritising immediate profits over other considerations like community, locality, workers and the environment.

Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World

Reviewed by Thomas Klikauer and Thu Nguyen

This is the context for Brett Christophers’ [2023] book Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World, which discusses global asset managers, their dominance and the impact they have on society.

Christophers’ noteworthy book is an outstanding contribution for several reasons. It innovatively distinguishes between what the author calls an ‘asset manager society’ and neoliberal capitalism as we know it. According to Christophers, asset managers blur the boundaries between finance, society and capitalism. To fully understand their roles in a capitalist society, the macroeconomic context in which asset managers operate needs to be placed at the centre of any discussion on the role of asset managers. Inevitably, this raises the question of whether asset managers’ power over substantial financial resources can be challenged by policies that, ultimately, can lead to more humane and environmentally friendly investments.

The first two chapters offer a financial history that reaches well beyond the post-2008 macroeconomic conditions of the global financial crisis. Yet, Christophers does not shy away from a strong critique of a seemingly now dominant ‘asset manager society’. This includes the core elements of the ‘asset management industry’, namely that investment funds are central to the asset manager society. This is a society saturated in […] debt’ (71).

Christophers correctly outlines the political implications of debt and the complex relationships that underpin the functioning of asset managers within this societal framework. He points out that ‘[y]ou might find yourself living in an apartment owned by a corporation such as Avalonbay Communities […] and asset managers collectively might own 40, 50 per cent, [or even more], of Avalonbay’s shares’ (23). It is not the investment fund itself. Rather, that is ‘borrows money and subsequently shoulders the debt’ (67).

Appropriately, the author critiques the dominance of debt within an asset manager society and discusses how it intertwines with promises made on behalf of various stakeholders. Christophers examines the considerable growth of the asset manager society following the global financial crisis. He analyses broader social issues and the worldwide acting investment institutions of wealthy nations, foremost the US, Canada, Europe and Australia.

Christophers shows the extensive reach and impact of firms like Blackstone, Brookfield and Macquarie in the housing market as well as the lack of transparency and public visibility surrounding unlisted infrastructure and real-estate funds. He offers the critique that ‘[e]ver since it came into being, asset manager society has been controversial’ (115) and ‘the world of asset management is cloaked in secrecy’ (116). However, ‘[i]n mid 2019, [one] firm reported that it owned more than 300,000 residential units around the world’ (151). He argues that ‘who ultimately makes money from them, and in what exact proportions – is surely a political problem as much as it is an empirical one’ (117).

This offers fresh insights and significant updates to the common narrative of neoliberalism. Christophers distinguishes between asset manager society and asset manager capitalism. The book contains an insightful exploration of asset managers while, simultaneously, revealing the hidden structures that shape the sector.

The next chapter does an admirable job of addressing challenges and complexities associated with asset managers’ involvement in managing essential infrastructure, signified in ‘[t]he costs incurred by residents and by the state in Bayonne and Missoula because of their water-supply systems […] ranging from “skimped” investment to increased user rates and heightened risk – are the costs associated with asset manager society more generally’ (164).

Christophers ingeniously uses Utopia or Dystopia to reflect on living in such a society and that the real existing asset manager society is far from ideals propagated by the apostles of business and capitalism. Like capitalism and neoliberalism, the asset manager society too creates oppressive structures and global inequality seriously impacting individual rights. He emphasises that ‘[a]sset manager society for those living in it […] such as the tenants of Summer House on the island of Alameda, […] is much more akin to a dystopia’ (164). Particularly, ‘a financialised owner-operator treats housing or infrastructure like a financial asset, thus “financialising” it’ (180). In fact, ‘the real-asset management landscape is characterised by intense churn, [as managers] buy residential or infrastructural assets […] only to put them in the shop window and sell them on just a handful of years later – often to other asset managers’ (188).

He criticises managers of closed-end funds and glorified traders who intensely churn out work based on ‘the golden rules of asset manager society’ (192): they prioritise work over everything else and maximise profits above all.

This leads Christophers to the inescapable question: who gains? When G7 leaders introduced a programme called ‘Build Back Better World’ (255), they promised to use private-sector investment for infrastructure in poorer countries to meet global needs and counter China’s influence. These asset managers, however, only focus on generating returns for investors. The false promises of the G7 and the reality behind it lead to an even more unequal wealth distribution. Christophers describes this in the following way: ‘[a]sset managers are more single-minded […] to make money for those whose capital they manage’ (209), while with regard to the universe of workers such as teachers, nurses, and firefighters, ‘such workers do not have significant retirement savings’ (224). Devastatingly, rather than making the world better as promised, they focus on ‘sharing the spoils’ (212).

This raises concerns about equity, capital access and financial beneficiaries. In other words, when asset managers invest ever more of other people’s funds into societal infrastructure, the widening disparities of asset-based inequality and social stratification become prominent political concerns (Adkins et al. 2020). Consequently, Christophers introduces ‘Scenario Two’ (216) to explore a different set of circumstances related to the themes of asset management, infrastructure investment and economic dynamics.

The final chapter – ‘The Future’ – is a reminder of the unpredictable character of an asset manager society. By using alliteration, ‘Problems, Problems’ (245) and ‘Crisis After Crisis’ (255), Christophers emphasises the importance of addressing contradictions to make visible the promises and realities of socio-economic development and sustainability.

He argues that if the Covid-19 pandemic or any future pandemic were to become endemic, it would signal a shift where a crisis is no longer ‘a’ crisis but becomes ever-present. This view reframes crises as a persistent element highlighting the need for adaptability and resilience in navigating continued uncertainties. Consequently, Christophers suggests that there is ‘an age of deep-seated crisis both in the provision of shelter and in the maintenance of a habitable geophysical environment’ around the world (257). Finally, the author also engages with the question: how does the return of inflation influence asset manager society? Virtually all of this comprises ‘[t]he distribution of financial gains within asset manager society’, where ‘essential infrastructures will increasingly be held in private hands’ (283). Specifically, ‘[i]n 2020, the amount of money managed by the global asset-management sector passed $100 trillion for the first time’ (287).

This emphasises the significant financial power of asset managers, positioning them as major players in the global financial scene. In short, Christophers’ book outlines what type of asset manager society is likely to emerge and what actions will be taken to get there.

In conclusion, the book is most insightful but also has some still unanswered questions. Whether workers and their pension portfolios – once invested into infrastructural and housing assets – can ‘take back control’ (Gibson-Graham et al. 2013) of their pension and mutual fund investments for more ethical purposes.

Broadly, in the wake of an ever-increasing power of monopolistic corporations, contemporary trends foster a trajectory towards an asset manager society. Increasingly, this will shape our lives. In the end, Christophers’ Our Lives in Their Portfolios calls for strategic thinking and preparedness to fight an economic and political landscape defined by asset managers and their substantial infrastructure investments.

24 April 2024

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HcxlWFSQnnU

SHOCKING Video of the Top US Economic Advisor Reveals the Truth

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW..............

- By Gus Leonisky at 9 May 2024 - 6:17am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

caca cash....

A viral video of President Joe Biden's chief economic adviser, Jared Bernstein, appearing to struggle to explain how monetary policy works has raised new questions about the administration's handling of the economy.

Bernstein, who chairs the White House Council of Economic Advisers, was interviewed for a new film called, "Finding the Money," a documentary made by advocates of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) – a controversial line of economic thought. One of MMT's central tenets is that government budget deficits don't matter for countries like the U.S. that borrow money in their own currencies. Proponents argue this means the government should use tax and spending policies to manage the economy and address inflation instead of the central bank's monetary policies.

CLICK TO WATCH BIDEN ECON MAN STRUGGLE TO EXPLAIN MONETARY POLICY

"The U.S. government can't go bankrupt, because we can print our own money," Bernstein says in the video. He was then asked by the interviewer, "Like you said, they print the dollar, so why does the government even borrow?"

Bernstein's reply seems to indicate uncertainty – at best – about monetary policy.

"Again, some of this stuff gets – some of the language and concepts are just confusing. The government definitely prints money, and it definitely lends that money by selling bonds. Is that what they do? They sell bonds, yeah, they sell bonds. Right? Since they sell bonds, and people buy the bonds, and lend them the money," Bernstein replied.

IMF SOUNDS ALARM ON BALLOONING US NATIONAL DEBT: 'SOMETHING WILL HAVE TO GIVE'

Bernstein, who chairs the White House Council of Economic Advisers, was interviewed for a new film called, "Finding the Money," a documentary made by advocates of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) – a controversial line of economic thought. One of MMT's central tenets is that government budget deficits don't matter for countries like the U.S. that borrow money in their own currencies. Proponents argue this means the government should use tax and spending policies to manage the economy and address inflation instead of the central bank's monetary policies.

CLICK TO WATCH BIDEN ECON MAN STRUGGLE TO EXPLAIN MONETARY POLICY

"A lot of times, at least to my ear with MMT, the language and the concepts can be kind of unnecessarily confusing but there is no question that the government prints money and then it uses that money to um, uh … I guess I'm just, I can't really, I don't get it, I don't know what they're talking about. . . . It's like, the government clearly prints money, it does it all the time, and it clearly borrows, otherwise you wouldn't be having this debt and deficit conversation. So I don't think there's anything confusing there."

https://www.foxbusiness.com/politics/white-house-economic-adviser-struggles-with-question-on-monetary-policy

MEANWHILE IN SWEDEN, THE NEW NATO COUNTRY...:

Transparency International annual Corruption Perceptions Index shows that Sweden is falling behind its Nordic neighbours. With 84 points, Sweden still belongs to the top of the least corrupt countries in the world, but is lagging behind Denmark, Norway and Finland.

One explanation to the first question and Sweden´s deteriorating ranking may be individually confirmed or suspected corruption cases which have gained particular attention. For example, the large bribery case in Region Skåne which cost tax payers >800 million SEK, or the news before the last election that 5 of 7 political parties are prepared to receive covert funding. The impact of these and other cases tend to negatively influence the perception of corruption and the trust in society at large.

Another survey which also offers a current view on the state of corruption in Sweden is the Nordic Business Ethics Survey based on 5,000 respondents in the private sector. It shows that 50% of respondents have observed bribes being offered or requested during the last year in their own company.

As to the second question, it is often said that we are naive, that there is a lack of understanding of how corruption works. For sure, continuous awareness raising and communication is important. Most organizations today have a policy and offer training to staff.

But equally important or even more importantly, when discussing anti-corruption, one should ask oneself what kind of governance and controls that the organization has implemented to manage corruption risks. What the exposure can be must be considered broadly in relation to the business and operating model, organizational structure, type of staff, markets, customers. What this all looks like will inform a risk-based approach, internal controls and due diligence processes to be properly equipped.

A common pitfall is a pre-primed mindset that there are no risks, or to limit the risk assessment to representation and gifts. Many organizations need to strengthen their processes in this area, or in some cases there are no processes or procedures in place yet. Plus, equally important, internal audit.

Louise BrownAn anti-corruption program can very well be compared to and be integrated with an internal fraud prevention program. An important component is the preparedness to act and manage incidents and be able to drive corrective actions without fear. The role of senior management and the tone at the top with regards to potential disruptions and troubleshooting should not be underestimated, given that revealed non-conformities and incidents impact business continuity and generate costly damages in terms of forensic measures, legal costs, delays, brand and reputational damage. The opposite is coined Fear of Finding Out.

https://advisense.com/2023/02/01/corruption-on-the-rise-in-sweden/

READ FROM TOP

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....

dangerous debt.....

Drowning in debt: The paralysis at the heart of the US fiscal crisis

Washington is doing nothing about its deteriorating finances because there is nothing it can do without risking major upheaval

By Henry Johnston

It can appear puzzling why at certain times in history a government facing a looming crisis simply does not address it. The problems accumulate in plain view while little is done to actually solve them. The human imagination being what it is, this inaction is inevitably attributed to some mix of corruption, malfeasance, and incompetence. And certainly the road to any system-level crisis is strewn with missteps and short-sighted policies. But there comes a point when the horizon of possibility has closed and there is simply nothing a government can do without unleashing forces that could easily overwhelm it.

In the strange and torpid final years of Tsarist rule in Russia, the unfolding crisis that would eventually result in the Russian Revolution seemed immobilized in a state of suspension as the country’s major actors recoiled from taking decisive actions for fear of detonating the very cataclysm they had sought to avoid. Much has been made of the weakness and indecision of Nicholas II, but by those fateful last years the anachronistic Romanoff dynasty was collapsing and little could be done to stop it.

Although the circumstances and specific crises bear little in common, a similar paralysis seems to have infected the US government as it confronts several intractable problems. A glaring example of this is that Ukraine’s impending defeat at the hands of a superior Russian military has put Washington in an impossible situation: it has proven incapable of delivering on its promise of inflicting a strategic defeat upon Russia, but the path available to it – negotiating with Russia as equals or, heaven forbid, from a position of weakness – is simply incompatible with the paradigm in which Washington operates.

No longer believing in victory, the US is not in any meaningful way helping Ukraine – nobody believes the recent aid package will actually change much. But a diplomatic solution could have the effect of laying bare America’s waning global influence and possibly even destroying NATO as a credible institution. With no good options, Washington is merely staggering along until events overtake it.

But Ukraine is hardly the worst of it. A crisis shaping up to be far more potent and deep-rooted is America’s rapidly deteriorating fiscal standing. And here again, policymakers seem paralyzed by their lack of scope to address what JPMorgan CEO Jamie Dimon thinks is “the most predictable crisis we’ve ever had.”

The crux of the matter is that the US government and economy at large had been overly dependent on a factor that, until quite recently, was taken for granted as being permanent: low interest rates and its corollary of low inflation. However, when interest rates moved higher, deficits suddenly mattered again. But the highly financialized US economy cannot easily be subjected to austerity to rein in the spiraling deficits. It is technically fraught, as we will discuss, even if it were politically possible. Meanwhile, the spending cuts that are possible are either a political powder keg or simply inconceivable to the ruling class.

Taking away the proverbial punch bowlBroadly speaking, interest rates had been falling for essentially four decades, a state of affairs largely attributable to the effects of globalization and entrenchment of the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. The integration of global financial markets allowed countries with high savings rates to subsidize American borrowing by buying US debt, thus putting downward pressure on interest rates. Another way to think about this is that for a long time the US was able to maintain low rates because it could export much of its inflation through global use of the dollar as other countries sterilized the newly printed dollars.

Meanwhile, the near-zero-rate world prevailing after the financial crisis of 2008-09 was an even more exotic milieu for the economy. Not surprisingly, debt levels exploded. Just since 2007, federal debt held by the public has surged from $4.6 trillion to an astounding $27.4 trillion. Overall government debt has now surpassed $34 trillion. And yet, despite the surge in debt, calamity did not strike and the government had no problem borrowing.

This bred a certain dismissiveness about the debt and deficits and helped a bi-partisan consensus coalesce in Washington around higher government spending, while the old budget hawks in Congress went extinct. And economists were sanguine: as recently as 2018, Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman called the debt an “absolutely trivial” worry. Others, such as Larry Summers, Jason Furman, and Olivier Blanchard, waxed eloquent about how interest rates would remain historically low indefinitely.

But everything changed in 2021, when a phenomenon thought all but eradicated from Western economies returned with a vengeance: inflation. In order to tame the price growth, the Federal Reserve embarked on a series of interest rate hikes that saw 10-year Treasury yields – the rate the federal government pays to lenders – post their sharpest rise in four decades.

The higher rates caused the interest expense owed by the government to surge. And quite suddenly, the US found itself on an utterly unsustainable fiscal path. Despite there not being a recession, the federal budget deficit effectively doubled to a staggering $2 trillion in the fiscal year through last September. One would be forgiven for thinking the US was shifting to a war-time economy. And it hasn't stopped there: the debt is increasing at a staggering clip of $1 trillion nearly every 100 days.

The interest expense on the debt has already surpassed defense spending – no small feat since the US isn’t exactly frugal about protecting its hegemony – and is on pace to grow at a blistering 30% year-on-year pace this year to reach $870 billion.

So what had appeared to be an appetizing free lunch turned out to be a mirage. The US is now learning a basic point of economic theory the hard way: deficits don’t matter as long as interest rates are low, because the cost of carrying the debt is manageable. And interest rates, in turn, can be low as long as inflation is under control. But when inflation rises, interest rates go up, and deficits balloon. So all else being equal, higher inflation means higher interest rates – meaning ever deeper deficits.

We have now come to the vicious feedback loop that has emerged at the heart of the interplay of interest rates, inflation, and deficits. Whereas before we saw low inflation allowing for low interest rates and thus easy-to-carry deficits, now we have the deficits themselves becoming a significant driver of inflation.

The reason this is happening has to do with the massive interest expense. We tend to think of interest only as an expense for the government. But for the investors who own US debt, it represents income. And since roughly three-quarters of US public debt is held domestically, most of that interest income stays at home. Clearly a good portion of it doesn’t find its way into the broader economy – most investors don’t take the interest income generated from their Treasury holdings to the grocery store – but enough of it does enter circulation to move the needle.

So paradoxically, higher interest rates amid high debt levels can actually create more inflation, not less. Another way to think about this is that when deficits are large, the stimulus effect from the fiscal side ends up overshadowing the constricting effect on private-sector lending that the higher interest rates produces.

What a financialized economy cannot tolerateIf we are now dealing with structurally high inflation – which the latest inflation prints seem to confirm – it will mean structurally higher interest rates. And yet, all else equal, higher interest rates mean lower asset prices (stocks, bonds, derivatives, real estate, etc.) This is because: first, the higher rate of return on risk-free savings offered by banks pulls some money out of assets; second, as the risk-free rate of return increases, the risk-adjusted return from investing in an asset decreases, thus lowering the price that investors are willing to pay for an asset today.

But the prospect of lower asset prices is a particularly acute problem for the US economy, which is now so financialized – meaning a large portion of income in the country is tied to asset prices – that a drop in asset prices will reverberate far and wide and trigger various knock-on effects. One such effect is a reduction in the tax intake by the government. In fact, an interesting pattern has emerged that underscores just how much the US tax base is dependent on asset prices.

The so-called ‘everything bubble’ of 2021 – when record-high valuations were recorded in a wide range of asset classes – led to a large increase in tax receipts the following year (up 21% year-on-year) when taxes on the income generated came due. However, when the Fed hiked interest rates in 2022, financial markets responded very negatively and asset prices went down. Sure enough, tax receipts in 2023 declined, and the deficit blew back out.

We are seeing this dynamic play out right now before our very eyes: hotter than expected inflation is compelling the Fed to hold off on rate cuts, which has dampened stocks.

So any attempt at austerity will push asset prices lower and thus suppress tax receipts – therefore having the perverse effect of actually exacerbating the deficit as more money needs to be borrowed to cover the difference. This is a cycle that is very difficult to extricate an economy from. And there is another risk in trying to somehow put the brakes on: a highly financialized debt-fueled economy does not respond to austerity in the same way that a more conventionally structured one does, because it’s never known where the leverage is or how large it is. Lehman’s balance sheet in 2008 had only $680 billion in assets and yet managed to detonate a global meltdown.

So to summarize, the return of inflation upset a balance that had evolved over many years whereby the US could run up ever higher debts without consequence. But the high interest rates blew out the deficit, which has meant more borrowing and, eventually, more inflation because high levels of deficit spending are inherently inflationary. The predicament is that it won’t be easy to bring down the deficit through austerity or by the type of financial tightening that would reduce asset prices – not least because the tax base is so dependent on asset prices.

Après moi, le délugeThe warnings of an impending fiscal crisis are coming fast and furious now, and they sound very different than before. If in years past one might have heard a call for fiscal responsibility couched in idealistic rhetoric touting America’s strength and rectitude – “History will show you there’s no country in history that’s been strong and free and bankrupt,” an old-school former Congressman from Tennessee, John Tanner, once said – today’s warnings are stark, immediate, and specific.

They sound more like what Joao Gomes, the vice dean of research at the Wharton business school, told the US Senate Budget Committee in March: “the coming fiscal crisis will be triggered by a sudden loss of confidence by the general public in the federal government’s finances and on those tasked with managing them.” “Its consequences will be severe and leave lasting – probably irreversible – scars on our economy and society,” he concluded.

But very little is being done to actually avert this outcome because there is little room for maneuver. An enormous and complex system that evolved over decades in a world of low interest rates cannot be transferred to new footing overnight – and certainly not without a lot of pain and political risk. The approach so far has been to simply keep spending and throw liquidity at anything that breaks in the financial system due to the higher interest rates.

The spending is, at least superficially, working. The economy is being touted as strong – a view, by the way, that most voters don’t buy – and the impressive growth figures of the past year or so seem to back that up. But a lot of this growth is simply being fueled by the deficit spending ($1.6 trillion in fiscal year 2024). Give me a trillion and a half and I will show you a good time!

Meanwhile, any serious attempt to confront the deficits eventually runs into the brick wall of the entitlement programs. “If you want to deal with deficits, you’re going to have to deal with entitlements. That’s where the spending is,” said Rep. Tom Cole (R-Okla.), a senior member of the House Appropriations Committee, said a few years back. In other words, don’t bother coming to talk to his committee.

And in fact, Congress only debates 28 cents of every dollar it spends; the vast majority of federal spending is mandated by statute and takes place outside the budget appropriations process. These are primarily related to the major healthcare and benefits programs.

It has been understood for decades that the entitlement programs are unsustainable, and now the surge of retiring baby boomers is only adding to the strain. But the system has been left in its dysfunctional state indefinitely because as long as debt was cheap the government could borrow its way through. The dirty not-so secret behind Social Security, for example, is that payroll taxes collected in the past were not actually invested or saved to pay for future obligations but were spent immediately to finance other government needs. This means that there’s not actually a trust fund to draw down; there is only a government ledger to borrow against.

No politician has been willing to seriously consider major reforms to the entitlement programs. Such a foray would strike too close to the heart of America’s current social contract. But when rates were low, they didn’t have to: the day of reckoning could always be postponed.

Dialing back military spending would seem to be one possible avenue toward making some headway. At the very least, a prudent move would be to acknowledge that the cost of maintaining an empire and bankrolling the likes of Ukraine, Israel, Taiwan has suddenly become prohibitive and to back away from those commitments. But even this is inconceivable to the Washington establishment, as the recent Ukraine bill to string along a losing war demonstrates. Such a retreat would be too much at odds with what they see as the raison d’être of the American state.

Such an attitude is a bit reminiscent of when East Germany, against all common sense, rejected Gorbachev’s ‘glasnost’ and ‘perestroika’ reforms in the late 1980s, Otto Rheinhold, the leading theorist of the East German Communist Party posed the fundamental question with exceptional clarity: “What kind of right to exist would a capitalist GDR have alongside a capitalist Federal Republic?”

The leading theorists of the Washington establishment pose essentially the same question: what is America if not the globe’s indispensable state? Such rigidity only exacerbates the paralysis.

Swedish commentator Malcom Kyeyune observed that “the single most dangerous period for a political system is when it has ignored a looming crisis for years and decades, and then finally, backs snugly perched against a wall that cannot be moved, tries to apply wide-reaching reforms.”

Just as the French monarchy’s financial woes on the eve of the convening of the Estates General in 1789 had, after decades of mismanagement, become an issue that could not be addressed by purely technical means, the problem of the looming fiscal crisis has moved far beyond the realm of economic policy.

Those holding the reins of power of the US government seem to sense the truth of Kyeyune’s words: they are doing as little as possible, because there is nothing they can do without wading right into that most dangerous period.

https://www.rt.com/business/596899-us-fiscal-crisis-debt/

MEANWHILE:

Putin lauds ‘important center’ of emerging multipolar world

A summit of the Eurasian Economic Union in Moscow coincided with the tenth anniversary of the group’s founding

Russian President Vladimir Putin hailed the important role being played by the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) in the emerging multipolar world in comments delivered during a summit of the group on Wednesday in Moscow.

The gathering coincided with the tenth anniversary of the signing of the EAEU’s foundational treaty that brought five post-Soviet states – Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia – together in a single integrated market. The group also has three observer states: Cuba and two other ex-Soviet nations, Moldova and Uzbekistan.

Speaking ahead of the closed-doors part of the summit, Putin lauded the bloc’s development, stating the union has fared well over the past decade and established itself “as an independent and self-sufficient center of the emerging multipolar world.”

The union strongly adheres to its “main principles of integration cooperation,” namely “equality, mutual benefit, respect for and consideration of each other’s interests,” Putin noted.

The economic indicators speak for themselves: according to available estimates, over the ten years the joint GDP of the EAEU countries went from $1.6 to $2.5 trillion. Trade with third countries grew by 60% from $579 to $923 billion, while the volume of mutual trade almost doubled: from $45 to $89 billion, with over 90% of transactions already made in national currencies,” Putin stated, noting that positive macroeconomic trends have been observed within the union this year as well.

The EAEU has proven to be beneficial not only to its member states, but to the broader Eurasian region, the president stated. The union “helps ensure stable and sustainable development both of the five member countries and the Eurasian region as a whole, and results in improving the quality of life and wellbeing of our people,” he said.

The EAEU is effectively a successor to the Eurasian Economic Community, a now-defunct group that existed between 2000 and 2014 but was dissolved soon after the EAEU treaty was signed.

https://www.rt.com/russia/597252-putin-eurasian-economic-union/

READ FROM TOP

FREE JULIAN ASSANGE NOW....