Search

Recent comments

- no angel....

4 min 46 sec ago - kompromat....

13 min 49 sec ago - no change....

44 min 6 sec ago - arrest that man.....

16 hours 43 min ago - monstrous...

19 hours 12 min ago - chomsky's advice....

21 hours 43 min ago - destroying america....

1 day 42 min ago - critic....

1 day 1 hour ago - talking....

1 day 2 hours ago - one nation's fairies....

1 day 3 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

the joker.....

Battle between death and night

The child was in front of this thing, silent, astonished, his eyes fixed.

For a man it would have been a gallows, for the child it was an apparition.

Where the man had seen the corpse, the child saw the ghost.

And then he didn't understand.

The attractions of the abyss are of all kinds; there was one at the top of this hill. The child took a step, then two. He went up, while wanting to go down, and approached, while wanting to go back.

He came very close, bold and trembling, to reconnoitre the ghost.

Arriving under the gallows, he raised his head and examined it.

The ghost was tarred. It glowed here and there. The child could see the face. It was coated with bitumen, and this mask which seemed viscous and sticky was modeled in the reflections of the night. The child saw the mouth which was a hole, the nose which was a hole, and the eyes which were holes. The body was wrapped and tied up in a large cloth soaked in naphtha. The canvas had become mouldy and broken. A knee went through. A crevasse revealed the ribs. Some parts were corpses, others skeletons. The face was the colour of earth; slugs, which had wandered over it, had left vague ribbons of silver. The canvas, stuck to the bones, offered reliefs, like the dress of a statue. The skull, cracked and split, had the gap of a rotten fruit. The teeth had remained human, they had preserved the laughter. A remnant of a cry seemed to rustle in the open mouth. There were a few stubble on his cheeks. The head, tilted, had an air of attention.

Repairs had recently been made. The face was freshly tarred, as well as the knee which stuck out from the canvas, and the ribs. Below the feet passed.

Just below, in the grass, we saw two shoes, rendered shapeless in the snow and rain. These shoes had fallen from this dead man.

The child, barefoot, looked at these shoes.

The wind, more and more worrying, had those interruptions which are part of the preparations for a storm; it had stopped altogether a few moments ago. The corpse no longer moved. The chain had the immobility of a plumb line. Like all newcomers in life, and taking into account the special pressure of his destiny, the child undoubtedly had within him that awakening of ideas specific to young years, which tries to open the brain and which resembles to the peck of the bird in the egg; but everything that was in his little consciousness at that moment was resolved into stupor. Excess sensation, it is the effect of too much oil, leads to the suffocation of thought. A man would have asked questions, the child did not; he looked.

The tar gave this face a wet appearance. Drops of bitumen frozen in what had been eyes looked like tears. Moreover, thanks to this bitumen, the damage caused by death was visibly slowed down, if not canceled out, and reduced to as little dilapidation as possible. What the child had in front of him was something that was taken care of. This man was obviously valuable. We did not want to keep him alive, but we wanted to keep him dead.

The gibbet was old, worm-eaten, although solid, and had been used for many years.

It was an immemorial custom in England to tar smugglers. They were hung on the seashore, coated with bitumen, and left hanging; the examples want the open air, and the tarmac examples keep better. This tar was of humanity. In this way we could renew the hanged men less often. We put gallows at intervals on the coast like street lamps today. The hanged man served as a lantern. In his own way, he enlightened his comrades, the smugglers. The smugglers, from afar, at sea, saw the gallows. Here's one, first warning; then another, second warning. This did not prevent smuggling; but the order is made up of these things. This fashion lasted in England until the beginning of this century. In 1822, three varnished hanged men could still be seen in front of Dover Castle. Moreover, the conservative process was not limited to smugglers. England took equal advantage of thieves, arsonists and murderers. John Painter, who set fire to the Portsmouth shipping stores, was hanged and tarred in 1776.

Abbot Coyer, who calls him Jean le Peintre, saw him again in 1777. John Painter was hanging and chained above the ruin he had made, and repainted from time to time. This corpse lasted, one could almost say lived, for almost fourteen years. He was still doing good service in 1788. In 1790, however, he had to be replaced. The Egyptians valued the mummy of a king; the people's mummy, it seems, can be useful too.

The wind, having a strong grip on the mound, had removed all the snow. The grass reappeared there, with a few thistles here and there. The hill was covered with this thick, short sea grass which makes the tops of the cliffs look like green cloth. Under the gallows, at the very point above which the tortured man's feet hung, there was a high and thick tuft, surprising on this thin ground. The corpses crumbled there for centuries explained this beauty of the grass. The earth feeds on man.

A lugubrious fascination held the child. He stood there, gaping. He only lowered his forehead for a moment for a nettle which stung his legs, and which made him feel like an animal. Then he stood up. He looked above him at this face that was looking at him. She looked at him all the more because she had no eyes. It was a widespread look, an indescribable fixity in which there was light and darkness, and which protruded from the skull and the teeth as well as from the empty eyebrows. The whole skull is watching, and it’s terrifying. No eyes, and you feel seen. Horror of larvae.

Little by little the child himself became terrible. He didn't move anymore. Torpor was taking over him. He did not realize that he was losing consciousness. He became numb and stiff. Winter delivered him silently to the night; there is a traitor in the winter. The child was almost a statue. The stone of cold entered his bones; the shadow, this reptile, crept into him. The drowsiness that emerges from the snow rises in man like a dark tide; the child was slowly overcome by an immobility resembling that of a corpse. He was going to fall asleep.

In the hand of sleep there is the finger of death. The child felt himself gripped by this hand. He was about to fall under the gallows. He already didn't know if he was standing anymore.

The end always imminent, no transition between being and no longer being, the return to the crucible, the slippage possible at any minute, it is this precipice which is creation. Law.

Another moment, and the child and the deceased, life in outline and life in ruins, would merge into the same erasure.

The spectre seemed to understand this and not want it. Suddenly he began to stir. It looked like he was warning the child. The wind was blowing again.

Nothing strange like this moving dead man.

The corpse at the end of the chain, pushed by the invisible breath, took an oblique attitude, rose to the left, then fell, rose to the right, and fell and rose again with the slow and funereal precision of a clapper. Fierce coming and going, We would have thought we saw in the darkness the pendulum of the clock of eternity.

It went on like this for some time. The child, faced with this agitation of the dead man, felt an awakening, and, through his cooling, was quite clearly afraid. The chain, with each oscillation, creaked with hideous regularity. She seemed to catch her breath, then start again. This squeak imitated a cicada song.

The approaches of a squall produce sudden surges of wind. Suddenly the breeze became a breeze. The oscillation of the corpse increased mournfully. It was no longer a rocking, it was a shaking. The squeaking chain screamed.

It seemed that this cry was heard. If it was a call, it was obeyed. From the depths of the horizon, a loud noise came running.

It was the sound of wings.

An incident occurred, the stormy incident of cemeteries and solitudes, the arrival of a troop of crows.

Flying black spots pricked the cloud, pierced the mist, grew larger, approached, merged, thickened, hurrying towards the hill, uttering cries. It was like the arrival of a legion. This winged vermin of darkness fell on the gallows.

The child, frightened, backed away.

Swarms obey commands. The crows had gathered on the gallows. Not one was on the body. They were talking to each other. The croaking is awful. Howling, whistling, roaring, that’s life; croaking is a satisfied acceptance of putrefaction. We seem to hear the sound that the silence of the sepulchre makes as it breaks. The croak is a voice in which there is night. The child was frozen.

Even more from terror than from the cold.

The crows fell silent. One of them jumped on the skeleton. It was a signal. Everyone rushed, there was a cloud of wings, then all the feathers closed, and the hanged man disappeared under a swarm of black bulbs moving in the darkness. At this moment the dead man shook himself.

Was it him? Was it the wind? He gave a frightful jump. The hurricane, which was rising, came to his aid. The ghost went into convulsion. It was the gust, already blowing at full force, which took hold of him, and which agitated him in all directions. It became horrible. He began to struggle. Terrible puppet, having for string the chain of a gibbet. Some shadow parodist had grabbed his thread and was playing with this mummy. She spun and jumped as if ready to fall apart. The birds, frightened, flew away. It was like a reflection of all these infamous beasts. Then they came back. Then a struggle began.

The dead man seemed taken by a monstrous life. The breaths lifted him as if they were going to carry him away; one would have said that he was struggling and making an effort to escape; his straitjacket held him back. The birds echoed his every movement, retreating, then rushing, frightened and fierce. On the one hand, a strange attempted escape; on the other, the pursuit of a chained person. The dead man, pushed by all the spasms of the kiss, had jolts, shocks, fits of anger, came, went, rose, fell, pushing back the scattered swarm. The dead man was a club, the swarm was dust. The fierce attacking volley did not let go and persisted. The dead man, as if seized by madness under this pack of beaks, multiplied his blind strikes in the void, similar to the blows of a stone linked to a sling. At times he had all the claws and all the wings on him, then nothing; there were fainting spells of the horde, immediately followed by furious returns. Frightening torment continuing after life. The birds seemed frantic. The vents of hell must give passage to such swarms. Nails, pecks, croaking, tearing of shreds that were no longer flesh, creaking of the gallows, crumpling of the skeleton, rattling of scrap metal, cries of the gust, tumult, no struggle more lugubrious. A lemur against demons. Sort of spectre combat.

Sometimes, as the wind increased, the hanged man turned on himself, faced the swarm from all sides at once, seemed to want to run after the birds, and it seemed as if his teeth were trying to bite. He had the wind on his side, and the chain against him, as if dark gods were involved. The hurricane was part of the battle. The dead man was writhing, the flock of birds were rolling over him in a spiral. It was a whirlwind within a whirlwind.

We could hear an immense roaring below, which was the sea.

The child saw this dream. Suddenly he began to tremble in all his limbs, a shiver ran down his body, he staggered, shuddered, almost fell, turned around, pressed his forehead with both hands, as if the forehead were a point of support, and, haggard, hair blowing in the wind, striding down the hill, eyes closed, almost a ghost himself, he fled, leaving this torment behind him in the night.

VICTOR HUGO

TRANSLATION BY JULES LETAMBOUR

---------------------------

The Man Who Laughs (also published under the title By Order of the King from its subtitle in French)[1] is a novel by Victor Hugo, originally published in April 1869 under the French title L'Homme qui rit. It takes place in England beginning in 1690 and extends into the early 18th century reign of Queen Anne. It depicts England's royalty and aristocracy of the time as cruel and power-hungry. Hugo intended parallels with the France of Louis-Philippe and the Régence.[2]

The novel concerns the life of a young nobleman, also known as Gwynplaine, disfigured as a child (on the orders of the king), who travels with his protector and companion, the vagabond philosopher Ursus, and Dea, the baby girl he rescues during a storm. The novel is famous for Gwynplaine's mutilated face, stuck in a permanent laugh. The book has inspired many artists, dramatists and film-makers.[3]

Background

Hugo wrote The Man Who Laughs over a period of 15 months while he was living in the Channel Islands, having been exiled from his native France because of the controversial political content of his previous novels. Hugo's working title for this book was By Order of the King, but a friend suggested The Man Who Laughs.[citation needed] Despite an initially negative reception upon publication,[4][5] The Man Who Laughs is argued to be one of Hugo's greatest works.[6]

In his speech to the Lords, Gwynplaine asserts:

Je suis un symbole. Ô tout-puissants imbéciles que vous êtes, ouvrez les yeux. J’incarne Tout. Je représente l’humanité telle que ses maîtres l’ont faite.

I am a symbol. Oh, you all-powerful fools, open your eyes. I represent all. I embody humanity as its masters have made it.

— Gwynplaine, in Part 2, Book 8, Chapter VII[7]

Making a parallel between the mutilation of one man and of human experience, Hugo touches on a recurrent theme in his work "la misère", and criticizes both the nobility which in boredom resorts to violence and oppression and the passivity of the people, who submit to it and prefer laughter to struggle.[8]

A few of Hugo's drawings can be linked with the book and its themes. For instance, the lighthouses of Eddystone and the Casquets in Book II, Chapter XI in the first part, where the author contrasts three types of beacon or lighthouse ('Le phare des Casquets' and 'Le phare d'Eddystone' – both 1866. Hugo also drew 'Le Lever ou la Duchesse Josiane' in quill and brown ink, for Book VII, Chapter IV (Satan) in part 2.[9]

Plot

The novel is divided into two parts: La mer et la nuit (The sea and the night) and Par ordre du roi (On the king's command).

In late 17th-century England, a homeless boy named Gwynplaine rescues an infant girl during a snowstorm, her mother having frozen to death. They meet an itinerant carnival vendor who calls himself Ursus, and his pet wolf, Homo (whose name is a pun on the Latin saying "Homo homini lupus"). Gwynplaine's mouth has been mutilated into a perpetual grin; Ursus is initially horrified, then moved to pity, and he takes them in. 15 years later, Gwynplaine has grown into a strong young man, attractive except for his distorted visage. The girl, now named Dea, is blind, and has grown into a beautiful and innocent young woman. By touching his face, Dea concludes that Gwynplaine is perpetually happy. They fall in love. Ursus and his surrogate children earn a meagre living in the fairs of southern England. Gwynplaine keeps the lower half of his face concealed. In each town, Gwynplaine gives a stage performance in which the crowds are provoked to laughter when Gwynplaine reveals his grotesque face.

The spoiled and jaded Duchess Josiana, the illegitimate daughter of King James II, is bored by the dull routine of court. Her fiancé, David Dirry-Moir, to whom she has been engaged since infancy, tells Josiana that the only cure for her boredom is Gwynplaine. She attends one of Gwynplaine's performances, and is aroused by the combination of his virile grace and his facial deformity.[10] Gwynplaine is aroused by Josiana's physical beauty and haughty demeanor. Later, an agent of the royal court, Barkilphedro, who wishes to humiliate and destroy Josiana by compelling her to marry the 'clown' Gwynplaine, arrives at the caravan and compels Gwynplaine to follow him. Gwynplaine is ushered to a dungeon in London, where a physician named Hardquannone is being tortured to death. Hardquannone recognizes Gwynplaine, and identifies him as the boy whose abduction and disfigurement Hardquannone arranged 23 years earlier. A flashback relates the doctor's story.

During the reign of the despotic King James II, in 1685–1688, one of the King's enemies was Lord Linnaeus Clancharlie, Marquis of Corleone, who had fled to Switzerland. Upon the lord's death, the King arranged the abduction of his two-year-old son and legitimate heir, Fermain. The King sold Fermain to a band of wanderers called "Comprachicos", criminals who mutilate and disfigure children, and then force them to beg for alms or be exhibited as carnival freaks.

Confirming the story is a message in a bottle recently brought to Queen Anne. The message is the final confession from the Comprachicos, written in the certainty that their ship was about to founder in a storm. It explains how they renamed the boy "Gwynplaine", and abandoned him in a snowstorm before setting to sea. David Dirry-Moir is the illegitimate son of Lord Linnaeus. Now that Fermain is known to be alive, the inheritance promised to David on the condition of his marriage to Josiana will instead go to Fermain.

Gwynplaine is arrested and Barkilphedro lies to Ursus that Gwynplaine is dead. The frail Dea becomes ill with grief. The authorities condemn them to exile for illegally using a wolf in their shows.

Josiana has Gwynplaine secretly brought to her so that she may seduce him. She is interrupted by the delivery of a pronouncement from the Queen, informing Josiana that David has been disinherited, and the Duchess is now commanded to marry Gwynplaine. Josiana rejects Gwynplaine as a lover, but dutifully agrees to marry him.

Gwynplaine is instated as Lord Fermain Clancharlie, Marquis of Corleone, and permitted to sit in the House of Lords. When he addresses the peerage with a fiery speech against the gross inequality of the age, the other lords are provoked to laughter by Gwynplaine's clownish grin. David defends him and challenges a dozen Lords to duels, but he also challenges Gwynplaine whose speech had inadvertently condemned David's mother, who abandoned David's father to become the mistress of Charles II.

Gwynplaine renounces his peerage and travels to find Ursus and Dea. He is nearly driven to suicide when he is unable to find them. Learning that they are to be deported, he locates their ship and reunites with them. Dea is ecstatic, but abruptly dies due to complications brought on by an already weak heart and her loss of Gwynplaine.[why?] Ursus faints. Gwynplaine, as though in a trance, walks across the deck while speaking to the dead Dea, and throws himself overboard. When Ursus recovers, he finds Homo sitting at the ship's rail, howling at the sea.

Critique

Hugo's romantic novel The Man Who Laughs places its narrative in 17th-century England, where the relationships between the bourgeoisie and aristocracy are complicated by continual distancing from the lower class.[11] According to Algernon Charles Swinburne, "it is a book to be rightly read, not by the lamplight of realism, but by the sunlight of his imagination reflected upon ours."[12][13] Hugo's protagonist, Gwynplaine (a physically transgressive figure, something of a monster), transgresses these societal spheres by being reinstated from the lower class into the aristocracy—a movement which enabled Hugo to critique construction of social identity based upon class status. Stallybrass and White's "The Sewer, the Gaze and the Contaminating Touch" addresses several of the class theories regarding narrative figures transgressing class boundaries. Gwynplaine specifically can be seen to be the supreme embodiment of Stallybrass and White's "rat" analysis, meaning Hugo's protagonist is, in essence, a sliding signifier.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Man_Who_Laughs

---------------------

.....

Heretofore, I have referred only to Bob Kane; yet he was but one of the many persons whose creative talent went to make up the Batman Legend. With The Batman appearing in Detective Comics, World's Finest Comics, and Batman, as well as a newspaper strip which started in 1943, he couldn’t even do all the artwork. Jerry Robinson, Mort Meskin, Dick Sprang, Carmine Infantino, Win Mortimer, and Jim Mooney were some of the many artists who drew The Batman from time to time-although Bob Kane, as the creator, always had his name on it.

And Kane did not write the stories, though he often had a hand in creating the characters in them. One of the chief writers of The Batman for many years-in fact, the chief one-was Bill Finger. One sure sign of a Finger script was the presence of gigantic working models of everyday objects. They might be outdoor signs or indoor displays, but they were exact replicas of their smaller originals. His giant sewing machines really sewed; his giant phonographs played; and his giant paint tubes were chock full of real paint, ready to squirt in the Joker's face.

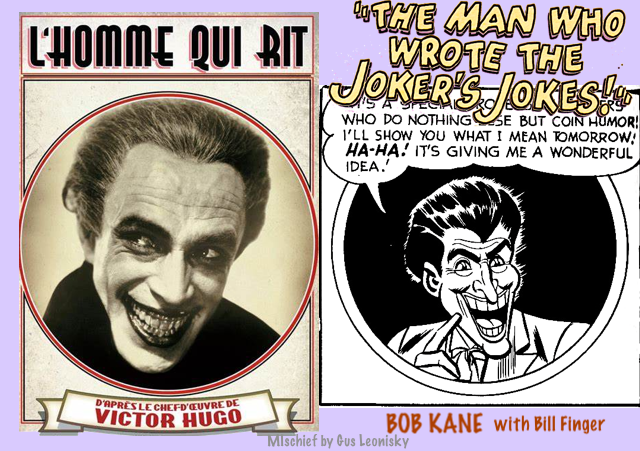

The Joker! Of all the villains The Batman has ever faced, this is the greatest. He is the perfect blend of clownish humor and malevolent evil. I have heard Bill Finger tell just how the character came to be created. It seems Bill got a call from Bob Kane. He had an idea for a villain Bill could use in the comics. He was a clownish-looking man, but a killer. However, when Bill saw Bob's sketch, he decided it looked too clownish. He happened to have a movie edition of Victor Hugo's The Man Who Laughs, with stills from the 1928 film starring Conrad Veidt. The story concerns Gwynplaine, an English nobleman stolen as an infant and turned into a carnival freak by having a perpetual laugh carved on his face. The makeup used by Veidt was perfect, and this inspired the Joker's grinning countenance.

Other villains quickly followed, including the Penguin, the Catwoman….

E. Nelson Bridwell (Editor and writer of Batman newspaper strip) — 1972

SEE ALSO:

harris and walz seize on joyful message in contrast to the biden/harris tanking economy......

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

- By Gus Leonisky at 12 Aug 2024 - 12:00pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

captain america....

Captain America is a fictional comic book character created by Jack Kirby and Joe Simon, first introduced to the world on March 1941 in 'Captain America #1'. Kirby and Simon created Captain America as propaganda, with the primary intent to promote America on entrance to WWII. A constant theme throughout the Captain America comics is the idea of war and Americas involvement in war. This forced Americans who read the comic book to be exposed to the pro-war propaganda. Real groups and people, such as Nazi's were portrayed as villains in these comics. The hate harboured towards these villains was then able to be translated to real life. Captain America comics also promoted the conceptualisation that a perfect American was created from entering war, through the main character, Captain America. Those opposing war initiatives (mothers, youth) were targeted by the medium of comics, as they were vastly popular amongst children and teenagers. Kirby and Simon, also directly benefited from Americas entry to war, giving them motive behind creating a propaganda icon. However, patriotism and war were popular culture during this time in America, making Captain America the perfect product to sell rather than a character with a hidden agenda. It can therefore be argued profit was the primary objective of Captain Americas creation. This use of hijacking pop culture to spread propaganda was far more beneficial in promoting ideals of war to a society in which the topic of war was controversial at the time, and made war easier for society to accept.

https://www.sace.sa.edu.au/documents/652891/3932077/Sample+2+-+Captain+America.pdf/c6d67f07-5f18-a520-b62e-d18be965dd6c?version=1.2#

COMICS SUCH AS SUPERMAN, SPIDERMAN, BATMAN (ABOVE) WERE CREATED TO EASILY CAPTURE THE ADVENTUROUS DEVELOPING (SIMPLE?) MINDS OF THE YOUTH INTO THE MOLD OF "MIGHT IS RIGHT" OF THE AMERICAN EMPIRE. THE FOES OF THESE HEROES RARELY DIED — OR WHEN THEY WENT TO PRISON THEY "ESCAPED" THROUGH CROOKERY AND CAME BACK FOR MORE "EVIL"... THE IDEA OF THE REOCCURRING VILLAINS MADE THE HEROES' "ESSENTIAL REPEATS" OF GREATER AND GREATER FEAT. THE PROPAGANDA WAS ASSURED....

READ FROM TOP

SEE ALSO: america wins...

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.