Search

Recent comments

- military heat....

42 min 13 sec ago - arseholic....

5 hours 25 min ago - cruelty....

6 hours 42 min ago - japan's gas....

7 hours 22 min ago - peacemonger....

8 hours 19 min ago - see also:

17 hours 20 min ago - calculus....

17 hours 34 min ago - UNAC/UHCP...

22 hours 14 min ago - crafty lingo....

23 hours 38 min ago - off food....

23 hours 47 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

jules letambour translates more about the french revolution: we want bread!....

…. : on the 27th of Ventose [the sixth month of the French Republican calendar (1793–1805), originally running from 19 February to 20 March.] there was agitation because of the rations; on the 1st Germinal [the seventh month in the French Republican Calendar. The month was named after the Latin word germen 'germination'. Germinal was the first month of the spring quarter], because of the petition of the Quinze-Vingts, and on the 7th, because of an insufficient distribution of bread. There was fear of a general movement for the décadi (The tenth day in a ten-day week) in the French Republican Calendar, a day of idleness and assembly in the sections. To prevent the dangers of a night meeting, it was decided that section assemblies would be held from one to four [PM]. This was only a very insignificant measure, and one which could not prevent the fight. It was clear that the main cause of these uprisings was the accusation brought against the former members of the public safety committee and the incarceration of the patriots. Many deputies wanted to renounce prosecutions which, even if they were just, they were certainly dangerous. Rouzet imagined a means which did away with passing judgment on the accused, and which at the same time saved their heads: it was ostracism. When a citizen made his name a subject of contention, Rouzet proposed banishing this citizen for a time. His proposal was not listened to. Merlin (de Thionville), an ardent Thermidorian and intrepid citizen himself, began to think that it would perhaps be better to avoid the struggle. He therefore proposed to convene the primary assemblies, to immediately put the Constitution into force, and to postpone the judgment of the defendants to the next legislature. Merlin (de Douai) strongly supported this opinion. Guyton-Morreau opened more firmly. “The procedure we are carrying out,” he said, “is a scandal: where should we stop if we pursue all those who have made more bloodthirsty motions than the one with which the defendants are accused? We really don't know if we are completing or starting the revolution again.” We were rightly appalled by the idea of abandoning, at such a moment, authority to a new Assembly; we also did not want to give France a Constitution as absurd as that of 93; it was therefore declared that there was no need to deliberate on the proposal of the two Merlins. As the procedure begun, too many people wanted it to continue for it to be abandoned; only it was decided that the Assembly, in order to be able to attend to its other concerns, would only take care of the hearing of the accused every odd day.

Such a decision was not made to calm the patriots. The day of the decade was used to excite each other. The section assemblies were very tumultuous; However, the feared movement did not take place. In the Quinze-Vingts section, we read a new petition, bolder than the first, and which was to be presented the next day. It was read, in fact, at the bar of the Convention. “Why,” it said, “is Paris without a municipality? why are popular societies closed? what has become of our harvests? why are the a assignats more degraded every day? why can the young people of the Palais-Royal assemble alone? why are patriots alone in prisons? The people finally want to be free; he knows that, when he is oppressed, insurrection is the first of his duties.” The petition was listened to amid the murmurs of a large part of the Assembly and the applause of the Mountain. The president, Pelet (de la Lozère), received the petitioners very roughly and dismissed them. The only satisfaction granted was to send the sections the list of detained patriots, so that they could judge whether there were any who deserved to be sent back.

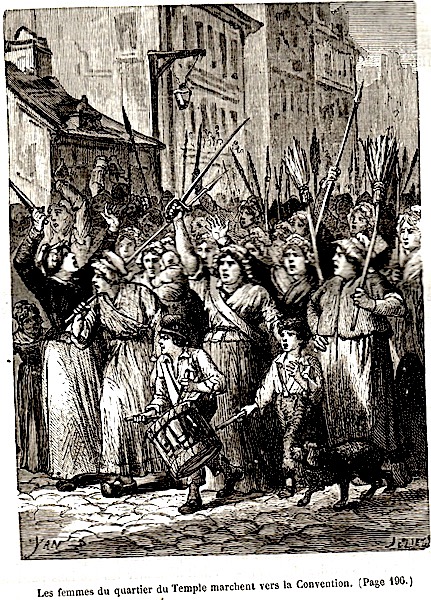

The rest of the day of the 11th was spent in unrest in the suburbs. It was said on all sides that it was necessary to go to the Convention the next day, to ask again for everything that we had not yet been able to obtain. This notice was transmitted from mouth to mouth in all the districts occupied by the patriots. The leaders of each section, without having a clearly defined goal, wanted to excite a universal gathering, and push the entire mass of the people towards the Convention. The next day, in fact, 12 Germinal (April 1), women and children rose up in the City section, and gathered at the bakers' doors, preventing those who were there from accepting rations, and trying to lead everyone towards the Tuileries. At the same time the leaders spread all kinds of rumours; they said that the Convention was going to leave for Châlons, and abandon the people of Paris to their misery: that the Gravilliers section had been disarmed during the night; that thirty thousand young people had gathered at the Champ de Mars, and that with their help the patriotic sections were going to be disarmed. They forced the authorities of the City section to give up their drums; they seized it, and began to beat the general call in all the streets. The fire spread quickly, the population of the Temple and the Faubourg Saint-Antoine rose up, and, following the quays and the boulevard, moved towards the Tuileries. Women, children, drunken men made up this formidable gathering; these later arrivals were armed with sticks, and wore these words written on their hats: Bread and the Constitution of 93. At that moment the Convention was listening to a report from Boissy-d'Anglas on the various systems adopted in matters of subsistence. It only had an ordinary guard behind hit: the gathering had reached her doors; it flooded the Carrousel, the Tuileries, and blocked all the avenues, so that the numerous patrols spread throughout Paris could not come to the aid of the national representation. The crowd entered the Liberty Room, which preceded the meeting room, and wanted to penetrate into the very heart of the Assembly. The bailiffs and the guard make an effort to stop them; men armed with sticks rush, disperse all who wanted to resist, rush against the doors, break them down, and finally overflow like a torrent into the middle of the assembly, uttering cries, waving their hats, and raising a cloud of dust. Bread! bread! The Constitution of 93! these are the words vociferated by this crowd. The deputies do not leave their seats, and show an imposing calm. Suddenly one of them gets up and shouts: Long live the republic! Everyone imitates him, and the crowd also utters the same cry, but it adds: Bread! the Constitution of 93! The single members on the left side burst out with some applause, and do not seem saddened to see the populace in their midst. This multitude, for whom no plan had been drawn up, whose leaders only wanted to use it to intimidate the Convention, spread among the deputies and sat down next to them. but without daring to allow any violence towards them. Legendre wants to speak. “If ever,” he said, “malice…” he won’t be let to continue. “Down! down! cries the multitude, we have no bread.” Merlin (from Thionville), still as courageous as in Mainz or the Vendée, leaves his place, goes down into the middle of the populace, speaks to these men, embraces them, is embraced by them, and urges them to respect the Convention. “Back to your place!” some mountain people shout to him. — My place, Merlin replies, is among the people. These men have just assured me that they have no bad intentions, that they do not want to impose their numbers on the Convention; - that, far from it, they will defend it, and that they are only here to make known the urgency of their needs, - Yes, yes, still cries the crowd, we want bread !"

TRANSLATION BY JULES LETAMBOUR.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

- By Gus Leonisky at 19 Aug 2024 - 7:28am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

rich kids.....

In Paris, a good deal of political violence was carried out by the so-called muscadins (‘perfume-wearers’) or jeunesse dorée (‘gilded youth’). Identifiable by their fashionable dress, their swagger and turns of phrase, most jeunesse dorée were young dandies from the bourgeoisie.

They came from the more affluent suburbs of central and western Paris; those that worked held professional positions in family businesses, law firms or the bureaucracy. The jeunesse dorée, through their wealth and connections, managed to avoid the bloodshed and military service of the revolution. The removal of Robespierre drew them out of hiding and onto the streets in defence of the new political order. Their politics were anti-Jacobin and moderate republican. They also tolerated royalists and some of their number were probably closet monarchists.

In late 1794 and 1795, the jeunesse dorée took to the streets like foppish, overdressed sans-culottes, condemning Jacobin policies, intimidating Jacobin sympathisers and destroying remnants of the old order. Much of this was minor or symbolic, however, gangs of jeunesse dorée went about armed with canes and clubs, beating Jacobin sympathisers and engaging in street battles with the sans-culottes. The jeunesse dorée were more likely to deliver a good thrashing than carry out political killings, however, their presence in Paris and some other cities was intimidating enough to contribute to the suppression of Jacobinism.

https://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/thermidorian-reaction/

The Jacobins were a late 18th-century political group organized during the French Revolution. The Jacobins organization, originally known as the Society of the Friends of the Constitution, operated under a radical left-wing republican ideology. What does "radical left-wing republican" mean?

Radical: as in extremist. Among all the political organizations formed around the French Revolution, the Jacobins desired massive socio-political upheaval through any means necessary (depending on the leadership at the time).

Left-wing: a political stance typically in support of socio-political change within an established hierarchical system. In this case, the Jacobins were against the established monarchy.

Republican: a somewhat broad term referring to a republican government, a sovereign state ruled by an elected minority that represents the citizen majority.

Under the foundational leadership of Maximilian Robespierre, the Jacobins became a violent and feared political group during the French Revolution.

https://www.studysmarter.co.uk/explanations/history/european-history/jacobins/

READ FROM TOP

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Picture above from Gus's collection...