Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

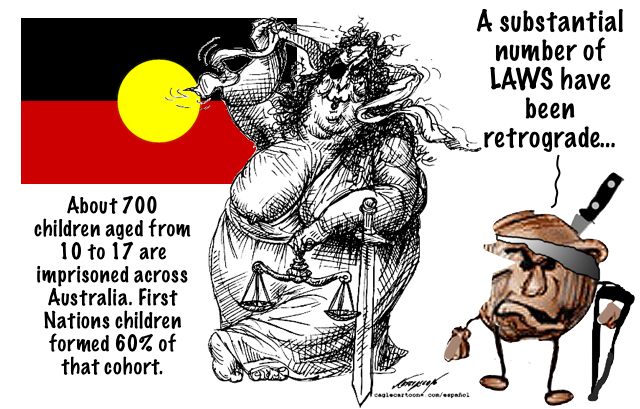

rough retrograde justice.....

In the last three years there has been a blizzard of new laws with respect to youth justice across Australia. While some laws have been welcome, a substantial number have been retrograde. In this category, laws with respect to young children have been the most controversial. This fact has attracted critical attention from a number of respected international and non-governmental human rights organisations.

Youth Justice: punishment or prevention? By Spencer Zifcak

Human Rights Watch in its 2025 Annual Survey, for example, wrote that Australia’s human rights record had been marred by State governments’ treatment of children in the criminal justice system. Authorities, it said, had subjected children to harsh conditions in detention including by imposing solitary confinement. It noted that in Queensland and Western Australia children had been incarcerated frequently in facilities designed for adults. On any given day about 700 children aged from 10 to 17 had been imprisoned across the country. First Nations children formed 60% of that cohort.

Of recent related measures, the one that has caused most alarm has been the lowering of the age limit at which children are regarded as assuming criminal responsibility for their actions. Currently New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, Western Australia and the Northern Territory have legislated to revise the age limit from 12 to 10. Very young children are now being imprisoned for a wide array of different offences.

In a General Comment on the implementation of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, the UN Committee on Children’s Rights recommends that the age at which children should be regarded as having an understanding of criminal behaviour and its consequences should be no lower than 14. Children below this age are still developing their frontal cortexes. This development affects their maturity and their capacity for abstract reasoning making them less likely to comprehend the consequences of their actions and to navigate criminal proceedings.

Children who encounter the criminal justice system are among the most vulnerable in the community. The Northern Territory’s Children’s Commissioner recently reported that 94% of children under 14 held in detention in 2022-23 had reported exposure to domestic or family violence.

Regrettably, law enforcement authorities in Queensland continue to detain children in police watch houses. This means that very young children may be incarcerated in close quarters to hardened adult prisoners. This is a clear breach of Article 37 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Article 37 that states unequivocally every child deprived of liberty shall be separated from adults.

In September 2024, an inspection report in Queensland revealed poor conditions in the Cairns and Murgon watch houses where children had been detained for weeks. The review highlighted overcrowding in Cairns watch house and a complete absence of natural light in cells and common areas. In Murgon children were deprived of fresh air with no outdoor exercise available.

In Western Australia, authorities detained a 17 year old boy in Unit 18, a wing of the maximum security Casuarina Prison. Last September, he committed suicide after having been transferred to the adjacent Banksia Hill Detention Centre. He had previously been held in Unit 18 where he had undergone an extended period of solitary confinement.

Last August the National Children’s Commissioner concluded in her report that children in the criminal justice system were experiencing the ‘most egregious breaches of human rights in Australia.’

Looked at generally Youth Detention should be governed by two fundamental principles. First, Article 3 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child provides that ‘in all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by welfare agencies…courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be the primary consideration.

It is difficult to reconcile this principle, for instance when ‘spithoods’ are mandated for children in their teens. Spithoods are total head coverings placed over prison children’s heads while they are handcuffed to a security chair.

Secondly, it is a key principle in Australian youth justice that young people should be kept in detention as a last resort and for the briefest period of time. The principle is contained in the legislation of every State and Territory. This principle is also embedded in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. Article 37(b) states that ‘No child shall be deprived of their liberty unlawfully. The arrest, detention or imprisonment of a child shall be in conformity with the law and shall be used only as a measure of last resort and for the shortest appropriate time.

As will be apparent, these two principles are all too often breached in practice in State jurisdictions, not least in circumstances where solitary confinement is prescribed.

Beyond the narrow sphere of children in detention for the commission of crimes, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, has also drawn the Australian government’s attention to the situation of asylum-seeker children. It has recommended that Australia prohibit the detention of asylum-seeking, refugee and migrant children.

Australia should enact legislation prohibiting the detention of children in regional processing countries. Furthermore, all relevant Australian authorities must ensure that the best interests of the child are a primary consideration in all decisions and agreements related to the relocation of asylum-seeking, refugee and migrant children within Australia.

There is no doubt that to some extent the intensification of harsh treatments of children in detention has been fanned by the recent trend amongst specific groups of children in major cities committing serious knife crimes. These offences have been more prevalent than in the past and the crimes committed by young perpetrators have become increasingly violent. But to react to violence with violence does not seem to be a strategy designed to succeed in either the medium or long term. Other rehabilitative reforms, offer the probability of greater success.

In this context therefore, State and Federal authorities should give serious consideration to the following recommendations.

- Australia should bring its laws, regulations and administrative practices fully in line with the terms of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

- The minimum age of criminal responsibility should be set at 14 years of age.

- Federal and State authorities should implement the 2018 recommendations of the Australian Law Reform Commission to reduce the high rates of incarceration of indigenous peoples, especially indigenous children.

- The techniques of isolation and force, especially solitary confinement and physical restraint, as methods of coercion or discipline of children should be prohibited.

- Non-judicial measures such as diversion, mediation and counselling for children accused of criminal offences should be deployed wherever possible. In more serious cases, children could be sentenced to non-custodial terms such as probation or community service.

- Young children should be provided with legal aid prior to and during court proceedings.

- Young offenders should be provided with bail assistance to reduce unnecessary remand, particularly where a child has no access to accommodation.

- Intensive rehabilitation programs should be provided to children in the course of their detention in order to minimise and mitigate their offending behaviour.

- The infrastructure in children’s detention facilities should be upgraded and improved.

- Concerted pre-and post-release support should be provided to young children leaving custody particularly with respect to accommodation, and re-integration into the wider community.

https://johnmenadue.com/youth-justice-punishment-or-prevention/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

HYPOCRISY ISN’T ONE OF THE SINS OF THE TEN COMMANDMENTS.

HENCE ITS POPULARITY IN THE ABRAHAMIC TRADITIONS…

- By Gus Leonisky at 1 Feb 2025 - 6:18am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

1 hour 5 min ago

1 hour 28 min ago

1 hour 33 min ago

12 hours 1 min ago

14 hours 45 min ago

14 hours 53 min ago

15 hours 29 min ago

17 hours 2 min ago

21 hours 22 min ago

21 hours 28 min ago