Search

Recent comments

- figurehead....

2 hours 32 min ago - jewish blood....

3 hours 31 min ago - tickled royals....

3 hours 39 min ago - cow bells....

17 hours 31 min ago - exiled....

22 hours 33 min ago - whitewashing a turd....

23 hours 32 min ago - send him back....

1 day 1 hour ago - the original...

1 day 2 hours ago - NZ leaks....

1 day 12 hours ago - help?....

1 day 13 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

your premium is linked to carbon dioxide and methane emissions.....

The big news on house insurance this week was the response of the insurance industry’s peak body to a parliamentary committee’s extensive criticisms of its treatment of people claiming on their policies after the massive floods of 2022.

The outlook for house insurance is much worse than we’re being told By Ross Gittins

The Insurance Council of Australia accepted some of the committee’s recommendations, announced an “industry action plan” and generally promised to be good boys in future. But the consumer groups were unimpressed.

Drew MacRae, of the Financial Rights Legal Centre, said the insurers “have a long way to go to restore trust and confidence in a sector that systematically failed customers during the 2022 floods. Today’s announced plan to get there is welcomed, but ‘trust us’ just won’t cut it”.

Meanwhile, in their pre-election campaigning, Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton are as one in portraying our insurance problem as a matter of misbehaving insurance companies.

Asked if he accepted a journalist’s claim that the companies had doubled premiums in recent years, “had plenty of money” and “are ripping us off”, Albanese flatly agreed. “We will certainly hold the insurance companies to account,” he added.

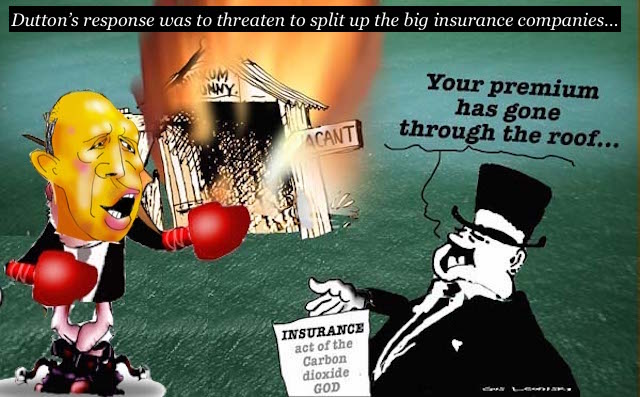

Dutton’s response was to threaten to split up the big insurance companies – until wiser heads in his team calmed him down.

Sorry, all this is delusional for some and, for others, a knowing attempt to mislead us on the seriousness of the problem. Have the insurance companies been behaving badly? Yes. Should they be forced to treat their customers fairly? Of course.

But will that fix the problem? No. Have the companies been ripping us off, putting up premiums just to increase their profits? No. They’ve been grappling with a problem they know they can’t solve: you can’t insure against climate change.

The cost of house insurance has been rising rapidly for several years because more bushfires, cyclones, storms and floods have led to more claims. We know that continuing climate change will cause extreme weather events to become more frequent and intense.

So the great likelihood is that house insurance premiums will just keep rising rapidly. The outfit that’s doing most to alert us to the deep trouble we have with insurance is the climate campaigning Australia Institute. Its recent national poll of 2000 people found that while 78% of home owners said their home was fully insured, 15% said they were underinsured and 4% said they were uninsured.

As house insurance premiums rise, more people will become underinsured — many with no insurance against flood damage, for instance — and more will be uninsured. Many of the latter will be people whose homes the companies have refused to insure.

The insurance companies know what’s coming, as do the banks and the government. They know what’s coming, but they don’t want to talk about it before it happens, mainly because they don’t know what to do about it.

Remember, insurance is an annual contract. So if I’m confident there’s little chance of your house being destroyed in the next 12 months, I’m happy to give you the assurance of insurance. But when, sometime in the future, I decide you’re a bigger risk, it will be a different story.

The point is, there’s no magic in insurance. It can do the possible, but not the impossible. The way insurance works is that, if I can gather a “pool” of many thousands of home owners, each with only the tiniest risk of having their house burn down, I can promise all of them that, in return for a modest premium, they’re all fully covered in the event of a major mishap.

A few of them will have such a mishap, but I can pay them out from the pool of premiums and still have enough left to make it worth my while being in the insurance business.

Once the risk of your home coming to grief becomes less than tiny, however, the game changes. When more than a few people in the pool make claims, I make no profit, or maybe a loss. So I can start by making owners with bigger risks pay more than those with low risks, but once your risk is too high, I can either charge you a premium that’s impossibly high, or just refuse you insurance.

Because of their ever-growing record of claims, the insurance companies are well-placed to make a reasonably accurate assessment of how risky it is to cover your house – even to the point of charging more in some parts of a suburb than others.

This means, of course, that home owners in some parts of the country will be charged far more than others. Premiums will be highest in northern Australia, where cyclone risk is higher, but also in areas where flooding or bushfires are likely. And even people living well away from harm in the inner city will be paying more to help out.

All this is why we should be doing more — and have been doing more this long time — as our part in the global effort to limit climate change. But what should we do to reduce the damage that’s arrived or is on its way?

Well, certainly not by having the government subsidise insurance. That would just encourage people to keep doing what they should stop doing. Taxpayers’ money should be used only to help people get away from the risk of fires and floods.

Just as fighting a fire is easier than fighting a flood, bushfires are less difficult to get away from than floods. We must start by preventing anyone else building in risky areas.

Then we need to move people off the flood plain. As for Lismore, the whole town needs to be moved to higher ground.

But here’s a tip. Don’t hold your breath waiting for Albanese or Dutton to raise these issues in the election campaign. That’s not the way losers behave.

https://johnmenadue.com/the-outlook-for-house-insurance-is-much-worse-than-were-being-told/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

SEE ALSO: https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/1048

SEE ALSO:

the lemming syndrome .....- By Gus Leonisky at 22 Mar 2025 - 6:44am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

of ppms...

Greenhouse gas emissions. Winning slowly or losing the battle?by David McEwen

With the election campaign already in full swing, what progress has Australia made towards emission reductions under Labor? Are we better informed and better prepared? David McEwen with some answers.

On an electricity grid-focused social media group, which is not generally frequented by the sort of brain-dead fossil trolls who will put a laughing emoji or inane comment on any post involving renewables or electric vehicles, I was recently accosted by a chap whose – apparently legit – profile identified him as a quality manager at an outdoor education provider.

His original post was a claim that delays in closing coal plants “do not lead to a negative climate impact.” He took objection to my assertion that winning slowly on climate is still losing, with a sarcastic sounding “ummmmm, no.” Five “m’s” – I counted.

Now, I’m right, and he (and the original poster) is flat-out wrong, but clearly, not enough people understand what should be basic physics and chemistry drummed into every high school student.

Here’s how it works.

A little goes a long wayCarbon dioxide is a trace gas in the atmosphere. About 0.04%, as Alan Jones was happy to remind us during the 2010s. Put another way, that’s 400 parts per million (ppm). If you’re thinking, like Alan, that there’s no way that a change in such a small concentration of carbon dioxide could make a difference, you might consider that it only takes about 1 milligram of arsenic per kilogram of body weight to kill someone. That’s just 1 ppm: food for thought, perhaps.

In 2024, the average was nearly 425 ppm and increasing at an accelerating rate.

When Charles Keeling first started taking measurements at Mauna Loa in Hawaii in 1958, the level was 311 ppm. Using tree-ring, ice-core and other data sources, scientists have demonstrated that the level at the start of the Industrial Revolution was about 280 ppm and had been relatively stable for the preceding several thousand years (as shown in Figure 1). This facilitated a reasonably consistent climate, allowing humans to learn agriculture and form increasingly complex societies.

That means that in the 66 years since direct observations began (a blink of an eye in the geological timescales these things normally take place over), the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has increased by 36%.

Over the last two hundred years, it’s up by over 50%. These are incredibly fast changes in climatic terms.

Carbon dioxide is one of a number of so-called greenhouse gases (GHGs) that re-radiate heat they receive from the sun. They work sort of like a blanket on a bed, trapping heat near the surface. Without these trace gases, it’s estimated that earth’s average temperature (i.e. all parts of earth over an entire year) would be about -18oC instead of the +15oC we are used to.

What’s happened as carbon dioxide has increased? Sure enough, observed average temperatures have increased, as shown below. Relative to when global temperature observations started in the mid-1800s, temperatures in 2024 were up over 1.5oC, with most of the rise ironically happening since the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, at which plans were made to do something about climate change.

To clarify, there is a logarithmic effect at play here. As carbon dioxide concentration increases, each additional unit has a smaller warming effect, which is why increasing the concentration of carbon dioxide by half has only increased temperatures by 1.5 degrees.

Scientists are in no doubt that the warming is due to humanity’s emissions of extra greenhouse gases, through digging up and burning enormous quantities of so-called fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – for our energy needs, clearing vast amounts of forest for our agricultural needs, exponentially increasing ruminant animal herds, and various chemical processes including making cement.

In the process, we’re also gravely threatening other planetary boundaries related to the preservation of the biodiverse ecosystems that underpin our economy and lives.

Urgency requiredAs concentrations of carbon dioxide (and other GHGs) have increased, so have global average temperatures, unleashing a range of deleterious impacts, including more frequent and severe extreme and destructive weather events, sea level rise, and ocean acidification leading to the collapse of marine ecosystems and food supplies.

Rising sea levels due to thermal expansion and melting land ice is already unstoppable, and we have locked in multi-metre rise over the coming centuries,

threatening a billion people living and farming in low-lying coastal areas.

Mr “outdoor education quality manager” might claim that these impacts won’t be catastrophic and, indeed, there could be positive outcomes. “CO2 is plant food,” he might post, omitting that you can have too much of a good thing, as those who have over-watered a house plant might attest.

However, recent research suggests that we reached “peak carbon sequestration” by plants over a decade ago. Meanwhile, many plant species thrive in a reasonably narrow band of optimal temperature and precipitation. More temperature extremes and less consistent rainfall – increasingly see-sawing abruptly from too much to too little – are far from conducive to high yields.

But aren’t we expecting global human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases like methane and nitrous oxide to peak soon and start declining? Hopefully, yes.

And given those graphs are all correlated, won’t that mean that as emissions start to reduce, then temperatures and carbon dioxide concentrations will also start to reduce? Unfortunately, in this case, correlation is not causation.

Because carbon dioxide, and almost every other greenhouse gas (except methane), are pretty stable molecules, they hang around in the atmosphere for a long time. Hundreds to many thousands of years. Because carbon dioxide is plant food and dissolves in water, about half of humanity’s excess emissions are removed from the atmosphere quite quickly.) But the other half persists for much longer, as you can see below.

Emissions are cumulativeThis means a lot of what we emitted into the atmosphere two hundred years ago is still there, still doing its warming trick, and,

a lot of the much greater annual amount we’re emitting today will still be around in another 200 years.

Back to our blanket on the bed example, it’s analogous to adding a new cover every year but not taking any away. In the 1800s, it was just a sheet added each year. Then it became a cotton throw, a woollen blanket, and now it’s a goose-down quilt. Emissions accumulate in the atmosphere.

Therefore, as emissions start to decrease, we’re still adding an extra cover to the bed each year; it’s just that they start to get thinner again. We’re still not taking any off. As such, the last ten years are simultaneously the coolest decade many adults will ever experience again and the hottest ten years on record.

If we make it to zero net emissions in a way the global climate system can respond to, rather than simply what it says on somebody’s offset spreadsheet), we can expect temperatures to stabilise at some ghastly new normal.

Even at zero net emissions, temperatures could keep rising due to arctic ice albedo, permafrost melting and releasing trapped methane. In addition, we also need to deal with a heating pulse associated with ditching our addiction to fossil fuels, given the current cooling effect benefit of some of the so-called aerosols released when we burn coal, oil and gas.

Your vote countsThe prognosis is grim, and global geopolitics are currently working against a safe future for humanity and the other species we cohabit with.

The only hope is for countries to elect governments committed to genuine, aggressive climate action.

And while Australia may seem to be an emissions minnow, we only account for about 1% of reported global emissions. In fact, our position as a major miner and exporter of both fossil fuels and metals such as iron ore, whose traditional processing produces vast amounts of emissions. According to ($) economist Adrian Blundell-Wignall,

Australia actually has influence over nearly 10% of global emissions.

Plus, we have the renewable resources (sun, wind, empty land and know-how) to significantly reduce our domestic and exported emissions while potentially growing the value of our exports, as explained in detail by economist Ross Garnaut. We just need the political focus and determination to make it happen.

https://michaelwest.com.au/greenhouse-gas-emissions-winning-slowly-or-losing-the-battle/

SEE ALSO: https://yourdemocracy.net/drupal/node/33287

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.