Search

Recent comments

- abusing kids.....

28 min 37 sec ago - brainwashed tim....

4 hours 48 min ago - embezzlers.....

4 hours 54 min ago - epstein connect....

5 hours 6 min ago - 腐敗....

5 hours 25 min ago - multicultural....

5 hours 31 min ago - figurehead....

8 hours 39 min ago - jewish blood....

9 hours 38 min ago - tickled royals....

9 hours 46 min ago - cow bells....

23 hours 38 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

trump is muddling in his own yuckraine meddlings.....

The speakers discuss the ongoing Ukraine war, criticizing U.S. involvement and framing it as a geopolitical trap for former President Trump, who they argue should have immediately withdrawn all support to Ukraine upon taking office. They believe that doing so would have ended the war early, with Russia still achieving most of its goals. They argue that Russia was always willing to negotiate for a neutral, demilitarized, and "denazified" Ukraine, but the West ignored this.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tGXmXH1YdzE

Col Douglas Macgregor - Trump's "Bear Trap" in Ukraine

They interpret recent Russian military gains (like in the Kursk and Belgorod regions) as a sign Putin has shifted from seeking negotiation to aiming for the complete defeat of the Ukrainian regime. They claim the West is living in a delusion, still believing a peace deal can be made without territorial concessions or demilitarization. According to them, this path only leads to prolonged conflict and missed opportunities for strategic alignment with Russia.

The conversation also touches on North Korea’s involvement in the war, describing it as symbolic and motivated by Kim Jong-un's desire for his troops to gain combat experience and show loyalty to Russia. They note the North Korean tactics were outdated and ineffective, but the gesture was more political than tactical.

In conclusion, they criticize what they see as U.S. arrogance and short-sightedness in foreign policy, arguing it has caused strategic losses, wasted lives, and alienated global partners. They suggest it’s time to abandon the illusion of American moral supremacy and reassess strategic realities, particularly regarding Russia and China.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

SEE ALSO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XIZa1wktN3Q

- By Gus Leonisky at 5 May 2025 - 5:19pm

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

a success.....

ACCORDING TO THIS VIDEO, THE NORTH KOREAN "HELP" IN THE KURSK REGION — DESPITE A FEW LOSSES — WAS A SUCCESS....

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-ntWnnxavE

North Korea is Now Officially at War With UkraineMAKE A DEAL PRONTO BEFORE THE SHIT HITS THE FAN:

NO NATO IN "UKRAINE" (WHAT'S LEFT OF IT)

THE DONBASS REPUBLICS ARE NOW BACK IN THE RUSSIAN FOLD — AS THEY USED TO BE PRIOR 1922. THE RUSSIANS WON'T ABANDON THESE AGAIN.

THESE WILL ALSO INCLUDE ODESSA, KHERSON AND KHARKIV.....

CRIMEA IS RUSSIAN — AS IT USED TO BE PRIOR 1954

TRANSNISTRIA WILL BE PART OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION.

A MEMORANDUM OF NON-AGGRESSION BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE USA.

EASY.

THE WEST KNOWS IT.

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

wrong history...

Notes from a 1991 meeting prove that the US, UK, France, and Germany assured the Soviet Union that NATO would not expand east. It’s part of a growing body of evidence that the West broke its promise to Russia.

A newly discovered document provides more evidence that Western governments broke their promise not to expand NATO eastward after German reunification.

Notes from a 1991 meeting between top US, British, French, and German officials confirm that there was a “general agreement that membership of NATO and security guarantees [are] unacceptable” for Central and Eastern Europe.

Germany’s diplomatic representative emphasized that the Soviet Union was promised in 1990 that “we would not extend NATO beyond the Elbe” river, in eastern Germany.

The document, which was formerly classified as secret, comes from the British National Archives.

It was made widely known this February by the German newspaper Der Spiegel, but was actually first published by US political scientist Joshua Shifrinson in 2019.

https://geopoliticaleconomy.com/2022/02/20/us-uk-france-russia-expand-nato-east-germany/

==============================

UP TIL THEN, VENERATED HISTORIANS HAVE SAID THAT NO GARANTEES WERE EVEN MADE AND THAT WAS "TOUGH TITTIES" (OR "UP YOURS") TO RUSSIA... YET WE CAN SAY THAT RUSSIA'S MEMORY IS BETTER THAN THAT OF THE WEST... THE WEST LIKES TO SURVIVE ON DECEIT AND BULLSHIT...

WHAT FOLLOWS IS TWO ARTICLES BY VENERATED HISTORIANS AND A DIOLOMAT THAT DISMISS RUSSIA'S VIEWS BECAUSE "History is nowadays not only written by the victors, but by anybody who wants to use history for their own ends."— Rodric Braithwaite

PREAMBLE:

Christopher Clark and Kristina Spohr say correctly (Moscow’s false memory syndrome, 25 May) that no written or oral assurances about Nato enlargement were given during the negotiations for German reunification in 1990. Touching that hot potato could indeed have derailed the talks entirely.

But that was far from all. After Germany reunited, Václav Havel, the Czech president, called for Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary to enter Nato. The British prime minister and foreign secretary assured Soviet ministers that there was no such intention. Nato’s secretary general added that enlargement would damage relations with the Soviet Union. All that was true at the time. But then the intentions changed.

Russian officials lament that Mikhail Gorbachev, then Soviet president, failed to get these oral assurances in writing. Not surprisingly, the Russians nevertheless believe that they were misled: imagine our reaction if the position were reversed. Historians will argue for generations how far that accounts for the subsequent deterioration in Russia’s relations with the west.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/26/the-west-assurances-to-soviet-ministers-on-eastward-expansion-of-nato

THIS PREAMBLE IS BULLSHIT....

----------------------

ARTICLE ONE:

Moscow’s account of Nato expansion is a case of false memory syndrome

This article is more than 9 years old

Christopher Clark and Kristina Spohr

Russia’s grievances today rest on a narrative of past betrayals, slights and humiliations. It’s time for a reality check

In April 2009, Mikhail Gorbachev expressed his outrage at the way Russia had been hoodwinked by the west in the years following German unification in 1990. After all, he told the German tabloid Bild, the western powers had pledged that “Nato would not move a centimetre to the east”. The failure to honour this commitment had poisoned Russia’s post-cold war relations with the west. “They probably rubbed their hands, rejoicing at having played a trick on the Russians,” he said.

The Russian president, Vladimir Putin, agrees. At the Munich security conference in 2007, he pointed to the threat posed by Nato’s expansion and asked: “What happened to the assurances our western partners made after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact?” In March 2014 he repeated the accusation that “they [the west] have lied to us many times, made decisions behind our backs ... This has happened with Nato’s expansion to the east.”

Is there any truth in this charge? Did the Nato partners offer a binding commitment to abstain from expansion into eastern Europe, and then renege on it?

In recent years, the bitterness of the Russian political elite against the west has been anchored above all in a sense of having been cheated by an unscrupulous opponent prepared to break international guarantees. But the memory of Nato’s broken promises also matters because it touches on the legitimacy, in Russian eyes, of the international settlement established during the German unification process and the European order that emerged in its wake. It has become one of the Putin government’s central arguments in the current Ukrainian crisis.

To assess this, we can consider an earlier moment of international crisis when the Russian political leadership claimed to have been duped. In 1908 the Russian minister of foreign affairs, Alexander Izvolski, hoped to secure improved terms of access to the Turkish Straits for Russian shipping. Since he had just signed a convention with Britain in the previous year, he was confident that London would back his efforts. But Austria-Hungary, Russia’s rival on the Balkan peninsula, was another matter.

In order to win Vienna’s support, Izvolski proposed that Austria annex the provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Austria agreed. But the somewhat shady deal left open the question of when exactly the Austrians would take their share. Fearing that the British might not be keen on opening the Straits to the Russians, Austria moved faster than expected and announced the annexation. London refused to back Izvolski’s bid for the straits, and the Russians were left empty-handed. Izvolski had drastically miscalculated: he had handed Bosnia-Herzegovina to Austria but got nothing in return.

Rather than acknowledge his own part in this debacle, Izvolski simply denied that there had been any agreement at all. The Russians, he claimed, had been robbed by Vienna. A storm of outrage broke across the Russian media, intensified by Slavophile fury fuelled by solidarity with orthodox, South Slav “little brothers” in the annexed provinces. A prolonged international crisis followed, during which Europe appeared to teeter on the edge of war. The crisis only came to an end months later, when Germany intervened on behalf of its Austrian ally and Izvolski backed down.

But the sense of outrage and humiliation within the Russian political elite persisted. In the political crises of the last years before the outbreak of war in 1914, the determination not to let Austria inflict further “humiliations” became a powerful Russian argument against compromise.In recent years, the tendency to misremember past debacles as humiliations has emerged as one of the salient features of the Kremlin’s conduct of international affairs. Amid recriminations over US and western European interventions in Kosovo, Libya and Syria, the Russian leadership has begun to question the legitimacy of the international agreements on which the current European order is founded. Among these, the centrepiece is the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany of 12 September 1990, also known as the Two-plus-Four Treaty because it was signed by the two Germanys, plus the US, the Soviet Union, Britain and France.

Yet the claim that the negotiations towards this treaty included guarantees barring Nato from expansion into Eastern Europe is entirely unfounded. In the discussions leading to the treaty, the Russians never raised the question of Nato enlargement, other than in respect of the former East Germany. Regarding this territory, it was agreed that after Soviet troop withdrawals German forces assigned to Nato could be deployed there but foreign Nato forces and nuclear weapons systems could not. There was no commitment to abstain in future from eastern Nato enlargement.

Vladimir Putin sees the matter differently. Pledges were made and broken; the Russians were “lied to” by their western partners; security guarantees were breached. And this retrospective reframing of the foundational 1990 agreement has profound consequences for Moscow’s view of its obligations under the post-cold war order. In a landmark speech at the Munich security conference last month the Russian foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, cast doubt on the legitimacy of German unification, proposing – to the baffled amusement of his audience – that it was less “legal” than the “reunification” of the Crimea with Russia. His comments followed an instruction from Sergei Naryshkin, the Chairman of the State Duma, that Russia’s Parliamentary Committee on International Relations consider passing a resolution denouncing the “annexation of the German Democratic Republic by the Federal Republic of Germany”. Russia’s own role in fixing the terms of German unification was now erased from memory, replaced by a mythical sequence of unmediated aggressions whose ultimate purpose was to justify current Russian policy in the Ukraine.

Looking back on the turbulent history of the European system since 1990 and the subsequent and totally unforeseen implosion of the Soviet Union the following year, it is too easy to fault the Russians for failing to insure themselves against the possibility of eastern European states joining the Atlantic alliance. These developments belonged to a future that was not yet in sight.

In a recent interview, Gorbachev distanced himself from earlier statements to concede that no agreements had been breached. “The topic of Nato expansion was not discussed at all. It wasn’t brought up in those years.” And when the issue arose later, in the early 1990s, “Russia at first did not object.” Following the Duma allegations of “annexation” of East Germany by West Germany, Gorbachev protested, warning that “our appraisal of the past should not be based on today’s views”. Sadly, it seems likely that this warning and others like it will fall on deaf ears in the Kremlin.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union there have been challenges and power plays on both sides. But misframing the past as a narrative of deceptions, betrayals and humiliations is a profoundly dangerous move. Today, as in 1908, tales of Russian victimisation play potently to domestic opinion. But projected on to international politics, they place in question the entire fabric of treaties and settlements that make up the post-cold war order.

The miracle of 1990 is that one of the greatest transformations of the international system in human history was achieved without war, in a spirit of dialogue and cooperation. The then Soviet leadership played a crucial role in that peaceful transition. Let us hope that its Russian successors do not prove to be its undoing.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/may/24/russia-nato-expansion-memory-grievances

WE KNOW THE REST OF THIS HISTORY: THE WEST DID ITS UTMOST TO TRY AND RAPE RUSSIA.... THEN PUTIN CAME ALONG AND STOPPED THE ROT IN THE BEST WAY POSSIBLE AT THE TIME...

============================

SECOND ARTICLE:

The uses and abuses of historyRodric Braithwaite

Christopher Clark, the distinguished author of a bestselling account of the outbreak of the First World War, has come up with an ingenious explanation of why the Russians are currently behaving so badly: they are suffering from ‘false memory syndrome.’ In a piece which Mr Clark wrote with Kristina Spohr in the Guardian on 25 May, he picks on the way Mr Putin has justified his annexation of Crimea when the Russian President claims that the West ‘has lied to us many times, made decisions behind our backs… This has happened with NATO’s expansion to the east.’

But, says Mr Clark, the Russians never asked for any guarantees that NATO would not enlarge, and none were given. Putin’s wayward handling of history matters, he contends, because it calls into question the European settlement, which emerged after the dramatic reunification of Germany in the autumn of 1990.

Putin is indeed rewriting history to encourage and exploit Russians’ sense of humiliation and so fuel his current adventurous and aggressive policies. But Mr Clark’s own account omits important facts, evades difficult issues of interpretation, and leaves unanalysed the practical and political pressures that surrounded the German negotiations and the events that followed.

Mr Clark is quite right that the Western side gave no written guarantees about NATO enlargement during the reunification negotiations. No responsible Russians have claimed otherwise. But he fails to ask why it was that no one raised the issue.

The great prize for the West was the reunification of Germany and its inclusion in NATO.

The great prize for the West was the reunification of Germany and its inclusion in NATO. But when the negotiations began in early 1990, it was not at all clear that Gorbachev would or could agree to either. His negotiating position was weak. Even if he realised that he would in the end have to concede, he also feared that domestic opposition to a deal might become overwhelming. The Western negotiators were acutely aware of that, and were anxious to nail the deal down before things fell apart in Moscow.

For either side explicitly to have raised NATO enlargement in that context could have derailed the negotiations entirely. So both sides had a motive for keeping their mouths shut: the West because they might have lost the prize, Gorbachev because he might have made his domestic position impossible. The fears were justified. Anger over Germany was one reason for the coup against Gorbachev in August 1991. And it remains one reason why many Russians now regard him as a traitor.

The underlying emotions bubbled to the surface on the morning of the signature of the reunification treaty in Moscow in September 1990. The British were still arguing about the language governing the deployment of NATO troops to East Germany. The Soviet foreign minister Eduard Shevardnadze threatened to boycott the signature ceremony, and Genscher, his German opposite number, had a fit. It was indeed a very fraught moment, but it was successfully papered over.

But the story does not stop there. Vaclav Havel, the Czech President, then called for Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Hungary to enter NATO. In the spring of 1991, the British Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary privately assured Soviet ministers that there was no such intention. Manfred Woerner, NATO’s secretary general, added publicly that enlargement would damage relations with the Soviet Union.

One can argue that Woerner was not expressing a settled NATO policy, or that what British ministers told the Russians in private didn’t matter, or that oral assurances have no force, or that what was said in 1991 was overtaken by events and became irrelevant. But it is not surprising that Russians took seriously these statements by apparently responsible Western officials, or that they now believe they were misled. Mr Clark does not tackle these matters.

It is not surprising that Russians now believe they were misled.

In early 1991 the West had not yet thought seriously about enlarging NATO. Western spokesmen were not being deliberately misleading, though there is little doubt that they would not have wanted to tie their hands, and that they would have rebuffed any Russian request for something in writing. But then their intentions changed.

The East Europeans wanted guarantees against a Russia that, they believed, would one day resume its menacing behaviour. NATO gave those guarantees in a fit of wishful thinking, apparently in the belief that Russian objections could be ignored because Russia would be flat on its back for the foreseeable future. Western politicians nevertheless tried to soothe Russian feelings with a one-sided ‘partnership’ with NATO, and assurances that enlargement would bring stability to Europe and thus benefit Russia too. The Russians failed to believe it. NATO is now left scurrying around to make its guarantees to the East Europeans look credible against a Russia that is indeed resurgent.

All these things are an essential and documented part of the story. They need to be brought into the historical narrative. It is a mystery why good historians ignore them.

Mr Clark argues more grandly that Putin’s behaviour is all of a piece with what he sees as the Russians’ unique ‘tendency to misremember past debacles as humiliations’, going back at least as far as their misjudged attempts to recover from the defeat they suffered at the hands of the Japanese in 1905. But there is nothing particularly unusual in this Russian behaviour. Historical memory and myth significantly affect the behaviour of other countries too: think only of France after the humiliation of 1871 or Germany after 1918.

Whether we choose to recognise it or not, many, perhaps a majority, of Russians nevertheless did feel humiliated by the collapse of the Soviet Union, the loss of international prestige, the political and economic chaos of the 1990s, and the brush with famine. Putin has plenty of promising raw material to work with. To ignore or downplay these things also distorts the historical record. And it makes it harder to understand what is going on in Russia today, and to devise appropriate policies to deal with it.

https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/uses-and-abuses-of-history/

WHAT HAS BEEN EXPLORED HERE IS THE COMPLEXITY OF WRITTING HISTORY WITH A SLANT AND WITHOUT HAVING ALL THE DOCUMENTS AT HAND...

Rodric Braithwaite, Christopher Clark and Kristina Spohr HAVE BEEN THUS PROVEN WRONG AND PUTIN RIGHT.

MAKE A DEAL PRONTO BEFORE THE SHIT HITS THE FAN:

NO NATO IN "UKRAINE" (WHAT'S LEFT OF IT)

THE DONBASS REPUBLICS ARE NOW BACK IN THE RUSSIAN FOLD — AS THEY USED TO BE PRIOR 1922. THE RUSSIANS WON'T ABANDON THESE AGAIN.

THESE WILL ALSO INCLUDE ODESSA, KHERSON AND KHARKIV.....

CRIMEA IS RUSSIAN — AS IT USED TO BE PRIOR 1954

TRANSNISTRIA WILL BE PART OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION.

A MEMORANDUM OF NON-AGGRESSION BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE USA.

EASY.

THE WEST KNOWS IT.

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

bad memory....

Western Memory of WWII is basically fan fiction

Xi Jinping will visit Russia at the invitation of Vladimir Putin and will attend the celebrations marking victory in the Great Patriotic War

By Andrey Kortunov

Historians seldom completely agree with one another even on some of the most important events of the past. There are different views on various historical events, such as World War II (WWII). With new documents being declassified and new excavations at the sites of the main battles, we are likely to see new theories and hypotheses emerging that will feed more discussions and offer contrarian narratives of the most devastating military conflict in the history of humanity.

However, there is a clear red line between looking for new facts and deliberately trying to falsify history. The former is a noble quest for truth and understanding, while the latter is a deplorable attempt to revise past events in favor of political goals or personal ambitions.

An honest scholar entering a research project cannot be completely sure what will be found at the end of the road; an unscrupulous politician presenting a falsified version of history knows perfectly well what picture to present to the target audience. Truth is skillfully mixed with lies, while fabrications are dissolved in real facts to make the picture more credible and attractive.

The most graphic manifestation of the WWII falsifications is the now very popular assertion that Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union were jointly responsible for the beginning of the war.

The narrative equating Nazis and Soviets is nonsensical because it completely ignores the history of fascism in Europe and repeated attempts by Moscow to convince London, Paris and Warsaw to form an alliance against it. Only after the “Munich Betrayal” by the West, the 1938 pact among Germany, the United Kingdom, France and Italy that forced Czechoslovakia to cede territory to Germany without Czechoslovakian consent, did Moscow decide to go for a non-aggression treaty with Germany to buy itself time before invasion.

Likewise, the dominant Western narrative of WWII increasingly frames the conflict as a stark moral battle between good and evil. As a result, there is a growing reluctance to fully acknowledge the pivotal roles that Russia and China played in the defeat of Nazi Germany and militarist Japan.

Neither do they recognize the contributions of communist-led resistance movements in countries like France, Italy, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Greece. This is largely due to ideological biases that exclude these groups from the dominant narrative of “heroic liberal forces” in the fight against the Axis nations, the coalition led by Germany, Italy, and Japan.

Instead, the predominant view in most Western countries credits the US as the primary force behind victory, along with limited support from other allies. This reading of WWII has nothing to do with reality, but it nicely fits the now popular Manichean interpretation of world politics.

Another typical distortion of history is the selective portrayal of the victims of the war, often shaped by a distinctly Eurocentric perspective. Much attention is given to the atrocities endured by Europeans under Nazi occupation or by Europeans in Asia at the hands of the Japanese, while the immense suffering of non-European populations frequently receives far less recognition.

Every human life is of equal value, and all victims deserve empathy. Even those who served in the German and Japanese armed forces during WWII should not be indiscriminately labeled as criminals; the notion of “collective guilt” must not override the principle of individual responsibility for verifiable war crimes.

However, it is often overlooked in contemporary Western discourse that the Soviet Union and China suffered the heaviest human cost of WWII – with casualties reaching 27 million and 35 million, respectively. A significant portion of these losses were civilians, and the scale and brutality of wartime atrocities committed on Soviet and Chinese territories far exceeded those experienced in most other regions.

Contemporary politics inevitably shapes how we interpret the past, as people often seek historical narratives that align with their present-day beliefs and agendas. Yet history should be approached with integrity, not as a tool to justify current political positions. This is not about defending national pride or preserving comforting myths; every nation, regardless of size or wealth, carries both moments of honor and episodes of regret in its historical journey. A balanced national narrative includes both triumphs and failures.

But when history is deliberately manipulated to serve short-term political interests, we risk blurring our understanding of the present and undermining our vision for the future. Such willful distortion is not only intellectually dishonest but could also lead to grave consequences.

This article was first published by CGTN.

https://www.rt.com/news/616817-western-memory-of-wwii/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

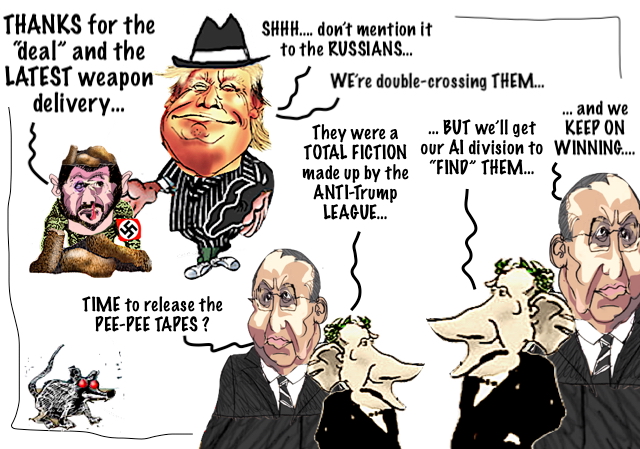

trump is double-dealing.....

Is Trump Selling Out to Zelensky and Neocons?

Donald Trump promised peace in 24 hours — but now he's arming Ukraine, just like Joe Biden, whom he blasted over the conflict.

Two Patriot Systems

A US Patriot air defense system from Israel will be heading to Ukraine, as Western allies weigh sending another, the NYT reported on May 4. Under US export laws, Patriot transfers need American approval — so the White House has given the nod.

F-16 Training and Equipment

Washington ok-ed a possible $310.5 million sale to Ukraine for F-16 training and support on May 2. It includes aircraft upgrades, personnel training, spare parts, software & hardware. Ukraine received its first F-16s from NATO last year.

$50M in Arms

The White House reportedly approved $50 million in arms exports to Ukraine through Direct Commercial Sales, the Ukrainian media wrote on May 1. The sale includes unspecified military hardware and services.

Mineral Deal Effect?

Trump's first weapons shipment to Ukraine followed the US signing of a 'mineral deal' with the Zelensky regime. Both sides call it a "win-win," but experts view it as a PR stunt, offering no immediate US profits or security guarantees for Ukraine.

Pentagon Arms Deliveries Continue

While Trump called for a ceasefire, the Pentagon continued arms deliveries to Ukraine from Biden-era packages after a brief pause in March. How does that align with ceasefire rhetoric? It's unclear.

MAGA is Starting to Suspect Something

Prominent MAGA lawmaker Marjorie Taylor Greene voiced frustration with Trump’s policies, questioning why the US would "occupy Ukraine," risk American lives, and spend billions defending its security and mining its minerals.

"I represent the base and when I’m frustrated and upset over the direction of things, you better be clear, the base is not happy. I campaigned for no more foreign wars," MTG tweeted on May 2.

https://sputnikglobe.com/20250505/is-trump-selling-out-to-zelensky-and-neocons-1121984537.html

FROM THE BEGINNING, TRUMP'S PLAN WAS TO DIDDLE THE RUSSIANS AND TO ROB THE UKRAINIANS... HE'S A MASTER OF DOUBLE DEALING....

TO THIS ADD "ROB THE PALESTINIANS" AND "BOMB YEMEN"... HE'S GENUINE LIKE A GANGSTER...

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.