Search

Recent comments

- seriously....

1 hour 2 min ago - monsters.....

1 hour 9 min ago - people for the people....

1 hour 46 min ago - abusing kids.....

3 hours 19 min ago - brainwashed tim....

7 hours 39 min ago - embezzlers.....

7 hours 45 min ago - epstein connect....

7 hours 56 min ago - 腐敗....

8 hours 15 min ago - multicultural....

8 hours 22 min ago - figurehead....

11 hours 30 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

gesturing toward change without actually changing....

Cardinal Robert Prevost of the United States has been picked to be the new leader of the Roman Catholic Church; he will be known as Pope Leo XIV.

Attention now turns to what vision the first US pope will bring.

New pope faces limits on changes he can make to the Church

Change is hard to bring about in the Catholic Church. During his pontificate, Francis often gestured toward change without actually changing church doctrines. He permitted discussion of ordaining married men in remote regions where populations were greatly underserved due to a lack of priests, but he did not actually allow it. On his own initiative, he set up a commission to study the possibility of ordaining women as deacons, but he did not follow it through.

However, he did allow priests to offer the Eucharist, the most important Catholic sacrament of the body and blood of Christ, to Catholics who had divorced and remarried without being granted an annulment.

Likewise, Francis did not change the official teaching that a sacramental marriage is between a man and a woman, but he did allow for the blessing of gay couples, in a manner that did appear to be a sanctioning of gay marriage.

To what degree will the new pope stand or not stand in continuity with Francis? As a scholar who has studied the writings and actions of the popes since the time of the Second Vatican Council, a series of meetings held to modernise the church from 1962 to 1965, I am aware that every pope comes with his own vision and his own agenda for leading the church.

Still, the popes who immediately preceded them set practical limits on what changes could be made. There were limitations on Francis as well; however, the new pope, I argue, will have more leeway because of the signals Francis sent.

The process of synodality

Francis initiated a process called “synodality”, a term that combines the Greek words for “journey” and “together”. Synodality involves gathering Catholics of various ranks and points of view to share their faith and pray with each other as they address challenges faced by the church today.

One of Francis’ favourite themes was inclusion. He carried forward the teaching of the Second Vatican Council that the Holy Spirit — that is, the Spirit of God who inspired the prophets and is believed to be sent by Christ among Christians in a special way — is at work throughout the whole church; it includes not only the hierarchy, but all of the church members. This belief constituted the core principle underlying synodality.

Francis launched a two-year global consultation process in October 2022, culminating in a synod in Rome in October 2024. Catholics all over the world offered their insights and opinions during this process. The synod discussed many issues, some of which were controversial, such as clerical sexual abuse, the need for oversight of bishops, the role of women in general and the ordination of women as deacons.

The final synod document did not offer conclusions on these topics, but rather aimed more at promoting the transformation of the entire Catholic Church into a synodal church in which Catholics tackle together the many challenges of the modern world. Francis refrained from issuing his own document in response, in order that the synod’s statement could stand on its own.

The process of synodality, in one sense, places limits on bishops and the pope by emphasising their need to listen closely to all church members before making decisions. In another sense, though, in the long run the process opens up the possibility for needed developments to take place when, and if, lay Catholics overwhelmingly testify that they believe the church should move in a certain direction.

Change is hard in the church

A pope, however, cannot simply reverse official positions that his immediate predecessors have been emphasising. Practically speaking, there needs to be a papacy, or two, during which a pope will either remain silent on matters that call for change or at least limit himself to hints and signals on such issues.

In 1864, Pius IX condemned the proposition that “the Church ought to be separated from the State, and the State from the Church”. It wasn’t until 1965 — some 100 years later — that the Second Vatican Council, in The Declaration on Religious Freedom, would affirm that “a wrong is done when government imposes upon its people, by force or fear or other means, the profession or repudiation of any religion".

A second major reason why popes may refrain from making top-down changes is that they may not want to operate like dictators issuing executive orders in an authoritarian manner. Francis was accused by his critics of acting in this way with his positions on Eucharist for those remarried without a prior annulment and on blessings for gay couples. The major thrust of his papacy, however, with his emphasis on synodality, was actually in the opposite direction.

Notably, when the Amazon Synod — held in Rome in October 2019 — voted 128-41 to allow for married priests in the Brazilian Amazon region, Francis rejected it as not being the appropriate time for such a significant change.

Past doctrines

The belief that the pope should express the faith of the people, and not simply his own personal opinions, is not a new insight from Francis.

The doctrine of papal infallibility, declared at the First Vatican Council in 1870, held that the pope, under certain conditions, could express the faith of the church without error.

The limitations and qualifications of this power include that the pope be speaking not personally, but in his official capacity as the head of the church; he must not be in heresy; he must be free of coercion and of sound mind; he must be addressing a matter of faith and morals; and he must consult relevant documents and other Catholics so that what he teaches represents not simply his own opinions, but the faith of the Church.

The Marian doctrines of the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption offer examples of the importance of consultation. The Immaculate Conception, proclaimed by Pope Pius IX in 1854, is the teaching that Mary, the mother of Jesus, was herself preserved from original sin, a stain inherited from Adam that Catholics believe all other human beings are born with, from the moment of her conception. The Assumption, proclaimed by Pius XII in 1950, is the doctrine that Mary was taken body and soul into heaven at the end of her earthly life.

The documents in which these doctrines were proclaimed stressed that the bishops of the church had been consulted and that the faith of the lay people was being affirmed.

Unity, above all

One of the main duties of the pope is to protect the unity of the Catholic Church. On one hand, making many changes quickly can lead to schism, an actual split in the community.

In 2022, for example, the Global Methodist Church split from the United Methodist Church over same-sex marriage and the ordination of noncelibate gay bishops. There have also been various schisms within the Anglican communion in recent years. The Catholic Church faces similar challenges but, so far, has been able to avoid schisms by limiting the actual changes being made.

On the other hand, not making reasonable changes that acknowledge positive developments in culture regarding issues such as the full inclusion of women or the dignity of gays and lesbians can result in the large-scale exit of members.

Pope Leo XIV, I argue, needs to be a spiritual leader, a person of vision, who can build upon the legacy of his immediate predecessors in such a way as to meet the challenges of the present moment. He already stated that he wants a synodal church that is “ close to the people who suffer”, signalling a great deal about the direction he will take.

If the new pope is able to update church teachings on some hot-button issues, it will be precisely because Francis set the stage for him.

Republished from THE CONVERSATION, May 9, 2025

Disclosure statement Dennis Doyle does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/05/new-pope-faces-limits-on-changes-he-can-make-to-the-church/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

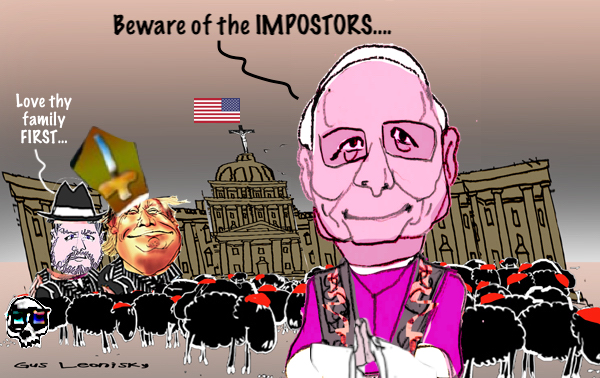

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

RABID ATHEIST.

- By Gus Leonisky at 10 May 2025 - 5:32am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

love thy.....

Prior to election, Pope Leo reposted articles criticising Trump and Vance

Prior to becoming pope, Leo XIV reposted social media articles criticising Vice President JD Vance's usage of Catholic doctrine to justify cancelling US foreign aid by arguing Christians should prioritise those close to them. "JD Vance is wrong: Jesus doesn't ask us to rank our love for others," read one headline shared by the then cardinal.

Pope Leo XIV shared articles criticising US President Donald Trump and Vice President JD Vance on social media months before his election as America's first pontiff, particularly on issues of migration.

In February, the then-Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost reposted on X a headline and a link to an essay saying Vance was "wrong" to quote Catholic doctrine to support Washington's cancellation of foreign aid.

The Vatican confirmed Thursday the account was genuine and belonged to the Chicago-born Prevost.

The article took issue with Vance, who converted to Catholicism in 2019 and argued that Christians should love their family first before prioritising the rest of the world.

"JD Vance is wrong: Jesus doesn't ask us to rank our love for others," said the headline reposted on Prevost's account, along with a link to the story by the National Catholic Reporter.

After becoming vice president, Vance justified the cancellation of nearly all US foreign assistance by quoting 12th-century theologian Thomas Aquinas's concept of "ordo amoris", or "order of love".

The late pope Francis, in a letter soon afterward to US bishops, said that "true ordo amoris" involved building "a fraternity open to all, without exception".

A few days later Prevost posted the headline and link of another article about Vance's doctrinal arguments, which referred to Francis's criticisms of Trump's mass deportations of migrants.

The future pope's last activity on X before his election on Thursday was to repost a comment by another user criticising the Trump administration's mistaken deportation of a migrant to El Salvador.

The post talked about "suffering" and asked, "Is your conscience not disturbed?"

The US president and vice president made no reference to the new pope's prior comments as they congratulated him on his election.

Vance, who met Francis briefly on Easter Sunday hours before the pontiff died, said: "May God bless him!"

"I'm sure millions of American Catholics and other Christians will pray for his successful work leading the Church," he said on X.

Trump, who had posted an AI-generated image of himself in papal clothes a few days earlier, said the election of the first pope from the United States was a "great honour for our country".

(FRANCE 24 with AFP)

https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20250508-first-us-pope-shared-articles-critical-of-trump-vance

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

betrayed....

‘We Were the First Christians’: Palestinian Believers Question American Evangelical Support for Israelby Timothy Shoemaker

Palestinian Christians in the West Bank are expressing a profound sense of betrayal as American evangelical leaders continue pushing for policies that directly harm their communities.

Nicholas Kristof recently traveled to Bethlehem to hear directly from Christians living under occupation – and their testimony stands in stark contrast to the narrative promoted by many American evangelical groups.

“Do we feel betrayed?” mused Mitri Raheb, a Lutheran Palestinian pastor who is President of Dar Al-Kalima University. “Yes, to some extent. Unfortunately, this is not new for us.”

The Roots of a Modern Movement

American evangelical support for the state of Israel didn’t emerge in a vacuum. It grew from seeds planted in the 1800s, when a theological idea called dispensationalism took root in Protestant circles.

A British preacher named John Nelson Darby first spread this teaching across America during speaking tours. Later, the Scofield Reference Bible – with its margin notes linking Old Testament prophecies to future events – carried these ideas into countless American churches.

Dispensationalism reads Bible prophecies about Israel with a rigid literalism. The ancient promises about land don’t belong to the Church, these teachers claim. They remain the property of ethnic Jews – waiting for fulfillment in our time.

This belief system found political opportunity after World War I. Christian voices helped push for the Balfour Declaration in 1917, which backed “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. When Israel declared statehood in 1948, many evangelicals saw divine prophecy unfolding before their eyes.

Cold War politics supercharged these religious convictions. As Israel aligned with America against Soviet influence, supporting Israel became both a spiritual and patriotic duty for many Christians.

Today, this theology drives concrete political action through organizations like Christians United for Israel – a group claiming 10 million members, dwarfing the better-known and politically-powerful AIPAC.

Lives Caught in the Crossfire

While American evangelical leaders urge President Trump to “reject all efforts” limiting Israeli control of the West Bank, flesh-and-blood Christians live under the policies these American churches champion.

They’re a minority twice over. Christians make up less than 2 percent of West Bank Palestinians today. But their small numbers can’t protect them from home demolitions, land seizures, and restricted movement – hardships they share with their Muslim neighbors in the shadow of expanding settlements.

In the Makhrour Valley near Bethlehem, Kristof met Alice Kisiya, 30, a member of an old Christian family. Kisiya said that she was physically attacked by Israeli settlers, that her family restaurant was torn down four times, and that she had been finally forced off her land last year by the Israeli government. She also pointed to where she said the Israeli authorities had knocked down a wooden church her family had built.

When asked about American Christian leaders who cite biblical authority for supporting these policies, Kisiya responded: “Let them come and live here so they can maybe deal with the settlers.”

When Ancient Text Collide With Modern Politics

The gap between biblical Israel and today’s nation-state spans nearly 2,000 years. They share a name but little else. One was an ancient kingdom; the other, a modern political entity established in 1948.

Many scholars who’ve devoted their lives to Scripture note a profound contradiction here. The New Testament repeatedly transforms promises about land into something broader – a covenant extending to all peoples through Christ (e.g., Galatians 3:28-29, Romans 9-11). Yet this nuance gets lost when ancient texts become modern political blueprints.

Daoud Kuttab has witnessed this contradiction firsthand. As a Palestinian Christian writer whose new book State of Palestine NOW examines the conflict, he sees the spiritual damage.

“When the Bible is used to justify land theft and war crimes against civilians, it puts the faithful in an awkward position,” he said.

The irony cuts deeper still. Prime Minister Netanyahu embraces support from evangelical leaders whose end-times theology often includes the belief that Jewish people who don’t convert to Christianity will face divine judgment when Jesus returns. Strange friends indeed.

Living the Gospel Under Occupation

One of the most poignant examples of Palestinian Christian resilience is the Tent of Nations, a community established on the Nassar family farm near Bethlehem. Their slogan, prominently displayed at the entrance, declares: “We refuse to be enemies.”

Despite this commitment to peace, the Nassars have documented years of hardship: regular assaults by settlers, destruction of their olive trees, denial of access to running water and electricity, and prohibition against building new structures on their own land.

Daoud Nassar, as he showed Kristof around the family farm, expressed deep disappointment that American Christian leaders remain silent about the repression of their fellow Christians in the holy land.

“Persecution is happening,” he said, noting for example that some Christians and Muslims alike have difficulties getting permission to pray at religious sites in Jerusalem. American Christians can easily visit the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, where Jesus is said to have been crucified, but it’s harder for West Bank Christians to get permission to worship there.

The First Followers vs. Modern Politics

“We were the first followers of Christ,” Nassar reminded Kristof. American pulpits rarely mention this uncomfortable truth: the Christians of Palestine descend from the earliest followers of Jesus in history. Their ancestors walked the land with Christ himself.

Instead, many evangelical teachings transform Bible verses about ancient Israel into political mandates supporting modern military occupation. Palestinian believers wonder: What happened to Jesus’ words about caring for the oppressed? When did land claims become more sacred than the people living on that land?

The disconnect between American evangelical politics and the reality for Palestinian Christians highlights a broader tension between human rights principles and religious nationalism.

Trump’s ambassador to Israel, Mike Huckabee, a Baptist minister and former Governor of Arkansas, has gone as far as saying “There is really no such thing as a Palestinian,” while favoring Israel’s annexation of the West Bank.

Meanwhile, some international Christians attempt to provide a protective presence for vulnerable Palestinian communities. During Kristof’s visit, a Dutch Christian volunteer named Riet Bons-Storm, a retired theology professor, was staying in a cave on the Nassar farm (since they aren’t permitted to build new structures) and celebrating her 92nd birthday.

“We are like human shields,” she explained.

‘We Are Also People‘

Nassar expressed a desire for more American Christians to visit and witness the inequalities of life under occupation firsthand.

“We need the U.S. Christians to understand what is happening,” he said. He sighed and added, “We are also people.”

Four simple words carrying the weight of decades of violence. To be forgotten by the world is one thing. To be rendered invisible by those who share your faith cuts deeper.

The theological confusion between ancient covenant and modern nation has real victims. When American churches envision the Holy Land, they often see prophecy charts and political movements – not the Christians who’ve worshipped there alongside Peter and the Apostles since Pentecost.

This theological framework didn’t emerge from careful Bible study. It grew from 19th-century innovations that skip over the New Testament’s expansion of God’s family beyond ethnic boundaries. The consequences aren’t theoretical debates for seminary classrooms. They translate into demolished homes, uprooted olive groves, and families separated by checkpoints.

As American evangelical voices help shape U.S. policy toward Israel, Palestinian believers wonder: will their spiritual siblings ever recognize their existence? Or will biblical prophecy continue to be wielded like a weapon against those living in the very land where Jesus taught love for neighbors?

https://ronpaulinstitute.org/we-were-the-first-christians-palestinian-believers-question-american-evangelical-support-for-israel/

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.