Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

CONservatizmmmmmunist....

Political commentator and American Spectator editor Daniel Flynn’s excellent biography of the late Frank S. Meyer arrives at an opportune time for conservatives. The movement is embroiled in internal disputes and has splintered into multiple factions holding many mutually exclusive positions. Today’s right must find agreement on fundamental principles, and those are exactly what Meyer, a longtime senior editor of National Review and founder or cofounder of multiple still-important conservative institutions, provided in the 1950s and ’60s.

[GUSNOTE: WAR IS STILL PART OF THE MIX OF AMERICAN CONSERVATISM IDEOLOGIES... PRESENTLY THE GLOBAL SOUTH IS REJECTING THE ONE-WAY TRAFFIC OF AMERICAN "INTERNATIONALISM" (GLOBALISM) — DUMPING THE AMERICAN RULES-BASED ORDER AND ITS FINANCIAL CONTROL — AND AMERICAN TRADITIONAL VALUES ARE STILL BASED ON RELIGIOUS DELUSIONS... THE NEO-CONS HAVE BEEN A CREATION OF ANOTHER JEW: LEO STRAUSS...]

As Flynn argues in The Man Who Invented Conservatism, Meyer really did lay the foundations for modern American conservatism, and his vision for the movement is still the best course for the American right. Meyer’s design for a politically, culturally, and intellectually viable American conservatism was called fusionism, which he developed and publicized widely through National Review magazine and individual conversations, especially by telephone, with others throughout the conservative movement, from the greats to the foot soldiers, plus his skill and delight in public meetings and debates.

Fusionism is commonly thought of as defining a political coalition comprising free-market economics, internationalism (initially anti-Communism), and traditional values. Although Meyer was the central figure in assembling that coalition, his idea of fusionism was first and foremost philosophical, arising from an analysis of the ideas of the American founding, which he undertook for a Communist organization in the 1940s. “Yes, a fervent Communist became the man who invented conservatism,” Flynn writes.

Flynn explores Meyer’s early life and Communist years at length to establish the unique mix of aptitudes and experiences that led Meyer to redefine conservatism. The biography breaks much new ground: Flynn found fifteen boxes of Meyer’s papers, including tens of thousands of letters, in a warehouse in Altoona, Pennsylvania, which had never been examined before.

Meyer, Flynn writes, grew up in a wealthy, bourgeois, liberal Jewish family in Newark, New Jersey. He emerged into adulthood as an atheist and a Communist. Egotistical, intellectually arrogant, and pugnacious, Meyer washed out of Princeton University in the late 1920s because of inattention to his studies and an apparent boost from institutional antisemitism. Meyer eventually got admitted to Oxford University, where he became a full-fledged Marxist and worked intensively for the Communist Party of Great Britain, “an instrument of the Soviet Union,” Flynn writes.

Meyer’s organizational, persuasive, and coalition-building skills were top-notch. “When Meyer entered Oxford, no Communist presence existed among students,” writes Flynn. “Now the oldest university in the world overflowed with Communists to a degree that caused notice in Parliament.” Meyer was equally successful in his other positions in the movement.

Meyer dutifully opposed the Nazis, embraced them, and rejected them as Moscow directed. In fact, Meyer took the Soviet Union’s fight against the Axis powers all too seriously: he joined the U.S. Army during World War II over his Communist superiors’ strenuous objections and interference. Inspired by his experiences with ordinary Americans in the Army, Meyer began to search for validation of Communism in the nation’s founding, “as the fusing of the ideas of the American leaders with the ideas of Marx, Engels, and Lenin,” he wrote to the head of the Communist Party of the USA (CPUSA) in 1943. “There was that word again: fuse,” Flynn writes.

After initial positive interest in his plan, the CPUSA ejected Meyer from the party. In addition, Meyer’s intensive engagement with the nation’s founding documents rapidly undermined his faith in Communism. Having married fellow American Communist worker Elsie Brown in 1935, Meyer moved the family to Woodstock, New York, always keeping a handgun nearby, even when sleeping. He supported Harry Truman in 1948 and began testifying against CPUSA leaders in criminal trials and congressional hearings a year later. “Frank, by now recognizing his past enterprise as profoundly evil, felt it his civic duty to tell the justice system what he knew,” writes Flynn.

Meyer began a career of public speaking, debates, writing in service of liberty, and attending to numerous friendships and rivalries within the conservative movement. In the wake of the Great Depression, the New Deal, and World War II, American conservatism was at a low point in the early 1950s, with the press and academia widely characterizing conservatives as a fringe outfit touting discarded ideas such as (“rapacious”) capitalism, (“dangerous”) “isolationism,” and (“ignorant and bigoted”) religious fundamentalism, all arising from the dreaded “authoritarian personality” type.

Meyer set about to counter those accusations by tying modern-day conservatism to America’s founding, as he had earlier set out to do for Communism. Although “the ex-Marxist initially tried to inventconservatism,” Meyer ultimately discovered it instead, Flynn writes. “An American conservatism, he argued, must conserve the American tradition, which is the ordered freedom inherent in the American Founding,” Flynn writes. “Thus he fused two disparate camps—traditionalists and libertarians—into one. This fusionism was his Big Idea.”

It was indeed. Meyer emerged as an important figure as a columnist and books editor at the new magazine National Review, which launched in 1955 and quickly became the flagship publication for the conservative movement. Meyer became the champion of the magazine’s libertarian wing, which was greatly outmanned by traditionalists such as Russell Kirk and liberal Republicans such as James Burnham. (All were strongly anticommunist.)

Meyer had inadvertently made an enemy of Kirk in 1953 by offering “a respectful if mixed review of The Conservative Mind, one of the seminal texts of the postwar conservative movement,” in The American Mercury. Once again mentioning fusion, Meyer wrote, “It is perhaps because of his implicit repudiation of the American fusion of individualism and conservatism that [Kirk] is more disappointing when he deals directly with contemporary men and situations.”

Through these internecine debates, Meyer arrived at a key insight into the relationship between liberty and virtue: “a person may act virtuously only when given the freedom to choose,” Flynn writes. Coercion is antithetical to virtue, Meyer found. “Freedom means freedom; not necessity, but choice between responsibility and irresponsibility; not duty but the choice between accepting and rejecting duty; not virtue, but the choice between virtue and vice,” Flynn writes.

That is a philosophical observation, not a political system, an ideology, or a strategy for acquisition of power. It was exactly what conservatism needed at that time: a coherent position on which to base a mass movement. “The most common misunderstanding regarded fusionism as a compromise of necessity to more easily obtain power,” Flynn writes. “That conservatives more easily obtained power after essentially adopting it as the movement’s default political philosophy served as this claim’s gravamen. This perspective necessarily conceives fusionism as not only a cynical calculation but an ideology — not developing organically but something syncretical invented by a theorist and therefore outside of conservatism.”

The Kirk-led conservative antipathy to rationalism and ideology obscured the importance of philosophical coherence in political thought. Fusionism, however, was not simply “the bromidic three-legged stool of social conservatism, smaller government, and a strong national defense,” Flynn writes. “Meyer did not petition traditionalists to give here and libertarians to give there.” On the contrary, fusionism was (and still is) an acknowledgment of the premises of the American founding — and, as Meyer argues in In Defense of Freedom, the liberal tradition which can trace its premises back at least two millennia and developed into America’s formula for ordered liberty.

Meyer argued for negative liberty, but in a new and characteristically American way. He (correctly) identified virtue as dependent on liberty instead of freedom being dependent on virtue. Also of immense importance, Meyer’s definition of the relationship between virtue and liberty undercuts leftism by removing the latter’s claimed monopoly on altruism and its characterization of government as reliably neutral and innately beneficial.

Fusionism also freed the right from the philosophical and political dead end of selfishness as a premise for liberty, as represented by Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, which has always been a political ball and chain. “Vote for us; we’re selfish!” is hardly an appealing campaign theme. For Meyer, individualism does not mean egocentrism; it means acknowledgment of the human condition, of the individual person as both “the central moral entity” and inherently social.

Meyer’s rethinking of conservatism implied a need for radical reforms, given how far the nation had drifted from its founding values and respect for individual rights. Meyer’s propensity for aggressive engagement, however, conflicted with traditionalists’ aversion to rapid change and libertarians’ antipathy toward government action. “The task of the American right involved not so much conserving as restoring,” Flynn writes. Meyer faced fierce opposition within National Review while receiving celebratory reviews of his magnum opus In Defense of Freedom, published in 1962.

Frustrated by his fellow National Review editors’ lack of enthusiasm for 1964 Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, Meyer set out to employ his great skill at organizing people around ideas and creating a mass movement. He helped found the American Conservative Union and successfully mentored leaders at Young Americans for Freedom, the Philadelphia Society, the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, and other organizations. “The former Stalinist organizer evangelized on the phone, from the lectern, and in his living room,” Flynn writes. “Meyer’s principles became what the conservative movement embraced, and his heresies became what it rejected. His most effective work increasingly took place outside of National Review.”

Meyer’s success became manifest in the election of Ronald Reagan as president in 1980. Unfortunately, Meyer did not live to see the political triumph of his vision, having died of cancer in 1972 at the age of 62, shortly after converting to Catholicism. “Ultimately, the Big Idea united the right,” Flynn writes. “The competing partisans, of freedom and individualism on the one hand and of order and virtue on the other, saw in fusion compelling reasons to reconcile their interests.” Reagan regularly praised Meyer and his ideas.

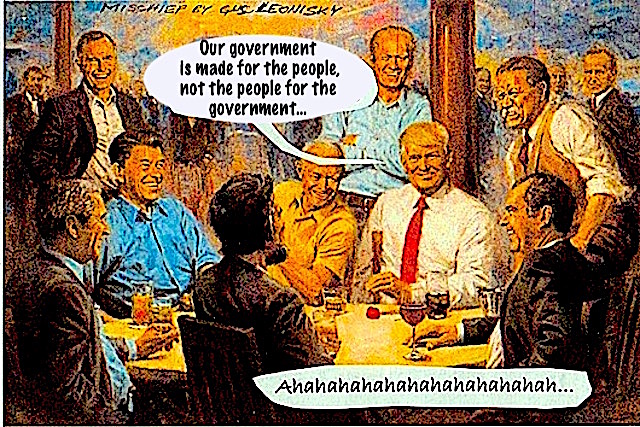

Though conservatism today is riven by intellectual and cultural divisions, its foundations, identified by Meyer, are still sound. Whereas leftism assumes that the individual exists to serve society, the United States is based on the recognition that government is made for the people, not the people for the government. Thus the right represents the real America, Meyer observed. With the progressive left having become openly anti-American in this century, the right’s response must be to embrace the nation’s founding principles, as Meyer did.

Meyer was an immensely important force on the intellectual right, giving American conservatism philosophical coherence and consistency and a historical pedigree that avoided turning the movement into an ideology. Meanwhile, Meyer strengthened conservatism’s ground game to implement policy based on those principles, not just talk about them, as Flynn’s book shows. The right can and should rally around Meyer’s formulation and judge its leaders today by the standards Meyer identified.

============

Meyer was born to a prominent business family of German Jewish descent[3][better source needed] in Newark, New Jersey, the son of Helene (Straus) and Jack F. Meyer.[3][4] He attended Princeton University for one year and then transferred to Balliol College at Oxford University, where he earned his B.A. in 1932 and his M.A. in 1934. He later studied at the London School of Economics and became the student union's president before he was expelled and deported in 1933 for his communist activism.[5]

Like a number of the founding senior editors of National Review magazine, Meyer was first a Communist Party USA apparatchik before he converted to political conservatism. His experiences as a communist are reported in his book The Moulding of Communists: The Training of the Communist Cadre in 1961. He began an "agonizing reappraisal of his communist beliefs" after he had read F. A. Hayek's The Road to Serfdom while he served in the US Army during World War II, and he made a complete break in 1945, after 14 years in active leadership service to the Communist Party and its cause.[6] Following the war, he contributed articles to the early free market periodical The Freeman, and he later joined the original staff of National Review in 1955.[citation needed]

After completing his turn to the right, Meyer became a close adviser to and confidant of William F. Buckley, Jr., the founder and editor of National Review, who, in the introduction to Buckley's book Did You Ever See a Dream Walking: American Conservative Thought in the 20th Century (1970), gave Meyer the credit for properly synthesizing the traditionalist and libertarian strains in conservatism, starting at the magazine itself.[7] Meyer wrote a column "Principles and Heresies", which appeared in each issue of the magazine; was its book review editor; and acted as a major spokesman for its principles.[citation needed]

Meyer married the former Elsie Bown. They had two sons, John Cornford Meyer, a lawyer, and then Eugene Bown Meyer, who became a president of the Federalist Society. Both sons hold international titles in chess. John is a FIDE Master, and Eugene holds the rank of International Master, just below Grandmaster.

Meyer converted to Catholicism just before he died of lung cancer in 1972.[8]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frank_Meyer_(political_philosopher)

GUSNOTE: THE LEFT AND THE RIGHT IN AMERICA FORM A "UNIPARTY"... TRUMP SEEMS TO BE INDEPENDENT FROM THIS, BUT HIS INTERNATIONAL (ERRATIC-CONTRADICTORY) ACTIONS ARE ON PAR WITH THIS UNIPARTY'S DESIRE TO RULE THE WORLD.

TRUMP'S DOMESTIC POLICIES ARE DESIGNED TO BRING CONSERVATISM TO THE HUGE AMERICAN MAJORITY WHICH PINES FOR "TRADITIONAL VALUES" AND FOR THE GOD DELUSION....

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

- By Gus Leonisky at 3 Sep 2025 - 9:08am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

6 min 55 sec ago

33 min 29 sec ago

2 hours 28 min ago

8 hours 25 min ago

9 hours 48 min ago

9 hours 56 min ago

20 hours 1 min ago

20 hours 45 min ago

21 hours 4 min ago

21 hours 11 min ago