Search

Recent comments

- no shipping.....

8 hours 45 min ago - digging graves....

8 hours 57 min ago - BS draft...

9 hours 5 min ago - tankers ablaze....

9 hours 51 min ago - shoes....

11 hours 49 min ago - new map....

12 hours 24 min ago - weapongeddon....

12 hours 40 min ago - squirming....

12 hours 57 min ago - UK kills russians...

17 hours 38 min ago - fury shit....

17 hours 47 min ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

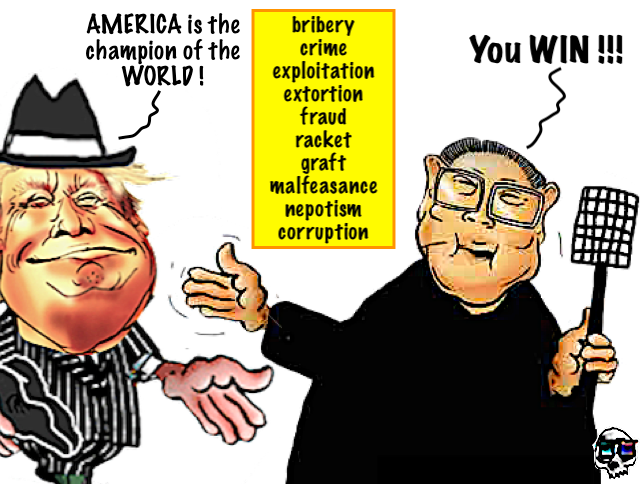

competitive corruption around the planet....

A key reason why China has, for decades, had the highest annual increases in per-capita GDP PPP (standard of living as experienced by the country’s population — as opposed to pure per-capita GDP, which reflects ONLY the investors) is the Chinese Communist Party’s relentless war against corruption.

China’s Constantly Intense Anti-Corruption Campaign

by Eric Zuesse. (All of my recent articles can be seen here.)

For example, on December 26th, the South China Morning Post headlined “Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign: China vows to keep up the fight” after record number of ‘tigers’ caught in corruption net: Politburo agrees to push forward campaign and calls for graft-busters to provide ‘guarantee’ for nation’s economic and social development”, and reported:

China’s ruling Communist Party has vowed to keep up efforts to fight corruption next year after a record 63 high-ranking officials – known as “tigers” – were placed under investigation on suspicion of graft in 2025.

During a meeting on Thursday, top decision-making body the Politburo also discussed a plan to improve conduct within the party, strengthen integrity and combat graft, official news agency Xinhua reported.

It said officials at the meeting had agreed to “resolutely push forward the fight against corruption, not stopping for a moment, not yielding an inch, and [to] deepen the comprehensive approach to addressing both the symptoms and root causes [of corruption]”.

The Politburo also called for the party’s discipline inspection and supervision bodies to push ahead next year with “higher standards and more effective measures” to provide a strong “guarantee” for China’s economic and social development in the five years to 2030. …

They heard a work report for 2025 from the top discipline and anti-corruption bodies, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection and the National Supervisory Commission, Xinhua said. …

The pledge to continue long-running efforts to combat corruption in China came a day after the CCDI announced that Wang Jun, a former deputy disciplinary chief in Tibet, had been detained.

Wang, who was also deputy director of Tibet’s regional legislature, became the 63rd tiger to be placed under investigation for corruption this year.

That is a new record since Xi launched the sweeping anti-corruption campaign in 2013. This year’s figure is about 9 per cent higher than the 58 senior officials caught in the corruption net last year, which was also a record high.

These “tigers” are among the country’s so-called centrally managed cadres that are usually ranked at the deputy ministerial level or above. Some hold slightly lower ranks but occupy key positions in important sectors.

They are directly managed by the party’s Central Organisation Department, its top personnel body, and face top-level investigation by the CCDI if they are suspected of any wrongdoing.

Dozens of top Chinese generals have also been removed this year in an ongoing crackdown on corruption in the military.

Among the most high-profile dismissals were He Weidong, a former Central Military Commission vice-chairman and a member of the Politburo, and Miao Hua, who was the ideology and personnel chief of the People’s Liberation Army.

Former Chinese senior banker Bai Tianhui executed for taking US$155 million in bribes

Separately, the CCDI on Wednesday released new guidelines for its investigators on obtaining and securing evidence.

A report on the CCDI website said the guidelines covered more than 20 types of corruption with a focus on “new and hidden forms” and they outlined key points for evidence collection and clarified evidentiary standards based on the elements of a crime.

The CCDI said it had sought feedback on the guidelines from legislative and judicial bodies.

In April, the graft-buster said corruption had become more sophisticated in recent years, with officials involved finding new ways to stay out of view.

That included waiting until after they had retired to receive bribes, and “revolving door” arrangements where officials used their knowledge for personal gain.

That same day, the American ‘news’-medium or propaganda agency Semafor headlined “China’s record graft crackdown” and opened with a seemingly informative graph marking each nation’s dot at its intersection between “GDP per capita” (the statistic that tells how good an economy is for investors) and the “Corruption perceptions index score” from Transparency International (TI). It showed China as being far more corrupt than the United States, and also being far lower GDP per capita than America is.

On 30 January 2024, I had headlined “Gallup Poll Confirms America’s Soaring Corruption”, and reported that,

Whereas the national corruption ratings of the various countries by the corrupt Transparency International organization, which was a spin-off from the U.S.-controlled World Bank in 1993 created by it so that countries whose leaders resist the demands by the U.S. Government will receive from TI poor corruption-ratings that scare away international investors and thereby starve their country of international capital and force up the interest-rates that those countries have to pay on their foreign debt, the people inside a given country — its own citizens there — have a much more realistic rating of their own country’s corruptness than do the hired outside ‘experts’ that TI selects to evaluate that in accord with TI’s vague criteria. Thus, the suite of Gallup polls that Gallup published on January 30th concerning Americans’ perceptions of “Honesty and Ethics” in America provides a far more accurate indication of the amount of corruptness in this country than TI’s score on this country does. So: here, I shall present the core from that Gallup article, and then will discuss it. …

Instead of the very opaque methodology of ranking that TI uses, which is based upon opinions by their selected panel of ‘experts’ to rate countries on their scale of countries’ transparency versus opaqueness, Gallup, on 18 October 2013, issued their polling-based study in which scientific random sampling of residents who were living in each country were asked to rate their own country, on the question “Is corruption widespread in your country, or not?” and that Gallup article was headlined “Government Corruption Viewed as Pervasive Worldwide”, and polled in and included 129 countries — but NOT China, perhaps because if China were to show as being the least corrupt, then Gallup’s income from the U.S.-and-allied billionaires’ corporations could plunge. Furthermore, only the data were being published by Gallup, no rankings that were based on them. That too would help protect Gallup from such possible blowback. In my article analysing those Gallup data, on 20 September 2020, I calculated and published the rankings based on those data, and my article on this was titled “Celebrating the Least Corrupt Country: Rwanda”. As I documented there, the Gallup rankings were extremely different from TI’s rankings, and the U.S. scored far better in the TI ranking than in the Gallup data. Of course, among other things, this means that the various nations’ bond-ratings, which depend largely upon TI’s ratings, significantly overstate the credit-worthiness of the U.S.Government.

On 5 August 09, I headlined “What is the world’s most corrupt country?”and opened:

Is it the country that corrupts the staff, the employees, of the U.N.? (No other country has the power to do that. This one does, and it takes full advantage of the opportunity, and carries out that corruption, ruthlessly.)

Is it the country that’s so corrupt at the very top, so that the model their aristocracy sets for their subjects to respect is so thoroughly rotten that this country has the world’s highest percentage of its people in prisons? If those prisoners are behind bars because they authentically should be, then that country is rotten at the bottom. But otherwise than that, there would have to be, above its bottom, at the level of the country’s entire criminal-justice system, a horrific amount of injustice, in order to place so many people behind bars, because this country’s having the world’s highest imprisonment-rate would then NOT reflect the prisoners’ extraordinary badness, but, instead, it would reflect the government’s extraordinary badness.

Though Gallup did not poll in China about this, two other major international polling organizations have polled there regarding closely related matters, and I wrote about this on 16 March 2023, headlining “How Nations’ Citizens Rate Their Own Government”. That presents the rankings from the international 2022 Edelman Trust Barometer, which scientifically sampled 36,000+ people in 27 countries, and 1,150+ people in each, concerning “Trust in Government,” on which the highest, where 91% said they trust their Government, was in China; then “Trust in Media,” on which the highest, where 80% said they trust their media, was in China; then “Trust in Business,” on which the highest, where 84% said they trust their businesses, was in China; then “Trust in National Health Authorities,” on which the highest, where 93% likewise did, was in China. The U.S. scored considerably below average on each of those measures. My article closed with:

Furthermore, the Edelman polls aren’t the only ones which show that China’s Government is extraordinarily good. On 22 August 2022, I headlined “NATO-Affiliated Poll in 53 Countries Finds Chinese the Most Think Their Country Is a Democracy” and reported that, “A poll in 53 countries by the NATO-affiliated “Alliance of Democracies” found that 83% of Chinese think that China is a democracy. That’s the highest percentage amongst all of the 53 countries surveyed.” And, the “U.S. was worse than average, and was tied at #s 40&41, out of the 53 nations, with Colombia, at 49%” — barely less than half of Americans think they live in a democracy.

Perhaps one of the major reasons why China’s economy performs far better than America’s does is that whereas China’s Government continuously fights extremely hard against corruption, America’s doesn’t really fight against it but instead FOR it (and America’s first-ever billionaire President, Trump, famously exemplifies this), and leads it — that’s American-style ‘freedom’. It’s a very different model. To the extent that there are ideological differences between the U.S. and China, that might be the biggest one of them all.

Investigative historian Eric Zuesse’s latest book, AMERICA’S EMPIRE OF EVIL: Hitler’s Posthumous Victory, and Why the Social Sciences Need to Change, is about how America took over the world after World War II in order to enslave it to U.S.-and-allied billionaires. Their cartels extract the world’s wealth by control of not only their ‘news’ media but the social ‘sciences’ — duping the public.

https://theduran.com/chinas-constantly-intense-anti-corruption-campaign/

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

SEE ALSO: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=17iKThi1eN0

Made In The USA: How America Built Its Own Destroyer (CHINA)

They call it the "Chinese Miracle," but history tells a different story: it was an American manufacturing job. In the 1970s, the U.S. government and corporate elites made a fatal calculation to open the doors to China in order to crush the Soviet Union. It worked—but at a devastating cost.

In this video, we expose the exact timeline of how American policy transferred wealth, technology, and industrial power to the East, accidentally creating the very rival they are now desperate to contain. From the Nixon shock to the WTO betrayal and the "Rare Earth" trap, discover how the U.S. didn't just lose the lead—they gave it away.

(WE KNEW.)

- By Gus Leonisky at 28 Dec 2025 - 4:44am

- Gus Leonisky's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the next geopolitical move: AI....

Jared Cohen is president of Global Affairs and co-head of the Goldman Sachs Global Institute.

George Lee is co-head of the Goldman Sachs Global Institute.

Executive summary- Next year will witness several key milestones for the future of generative AI. The world’s three largest democracies, and approximately 41% of the global population, will participate in national elections. AI will continue to accelerate and be adopted by state and commercial actors for everything from defense, to health care, to education, and more. At the end of 2024, we will have a better idea how AI will transform scientific discovery, labor, and the balance of power.

IntroductionEscalating competition between the US and China, wars in Europe and the Middle East, and shifting global alliances have ushered in the most unstable geopolitical period since the Cold War. At the same time, we are experiencing what may be the most significant innovation since the internet: the rise of generative artificial intelligence. With the public release of ChatGPT on November 30, 2022, the defining geopolitical and technological revolutions of our time collided.

Over the last 20 years, “traditional AI” has become pervasive, powering advertising algorithms, content recommendations, and social-media targeting. But its power and influence were largely shrouded and embedded within applications. Now, generative AI is front-and-center, with user interfaces that are commonplace, proficient, and clearly identifiable as machine-driven intelligence. Unlike previous technological revolutions, from the printing press to the internet, leaders in every capital and commercial center gained access to this tool at the same time, as ChatGPT became the fastest-adopted technology in history. While the technology’s future is uncertain, generative AI was nearly universally acknowledged as a paradigm-shifting innovation, not a fleeting trend or hype cycle. With widespread adoption and accelerating innovation, we have now entered a period we call the inter-AI years, when leaders in every sector are working to understand what generative AI will mean for them, and how they can take advantage of opportunities while mitigating risks.

This simultaneity does not imply parity. Different countries and companies have diverse histories, contexts, capabilities, and risk tolerance when it comes to AI. Notwithstanding these differences, leaders have the same window of maximum flexibility to shape an AI-enabled future. This window will be brief – a few years at most – then views and strategies will harden, and norms, values, and standards will be embedded within the technology. While the technology will continue to progress, decisions made today will determine what is possible in the future. Countries will have devised their approaches and formed likeminded blocs, competition will increase, the costs of changing course will rise, and the available paths for companies and countries will be more determined. What will emerge is a generative world order.

We are at the beginning of that order, and its future is uncertain. The long-term effects of technological revolutions are not made clear overnight – the Reformation did not immediately follow the invention of the printing press, and few could have predicted the positive and negative effects of social media in the early 2000s. But before long, the way we live and the nature of global politics will be shaped by generative AI. Which winners and losers will emerge? Will generative AI prove to be a zero-sum game, or create win-win scenarios? Will the problems that generative AI creates be solved by the very same technology, or will they prove to be intractable? Will companies or governments drive the future of AI? The relative nascency of this new node of AI innovation and the steep trajectory of improvement in generative AI models make these questions more momentous, and difficult to answer.

We believe that this is the time to take stock of where we are, and to identify some of the inflection points that will shape our AI future. This paper takes up the key changes in the generative AI field over the last year in the domains of geopolitics, technology, and markets. We discuss what trends are emerging, what debates remain unsettled, and how the generative world order is being defined.

AI and geopoliticsGeopolitical competition is a constant. But the technologies that animate that competition are not. And while the United States, China, and Russia do not agree on many things, they all acknowledge that AI could reshape the balance of power.

Today’s geopolitical rivals are putting AI at the center of their national strategies. In 2017, Russian President Vladimir Putin said, “Artificial intelligence is the future not only of Russia but of all of mankind.” Five years later, Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping declared, “We will focus on national strategic needs, gather strength to carry out indigenous and leading scientific and technological research, and resolutely win the battle in key core technologies.” And, in 2023, US President Joe Biden summarized what AI will mean for humanity: “We’re going to see more technological change in the next 10 – maybe the next 5 years – than we’ve seen in the last 50 years…Artificial intelligence is accelerating that change.”

Today, there are two AI superpowers, the United States and China. But they are not the only countries that will define the technology’s future. Earlier this year, we identified a category of geopolitical swing states – non-great powers with the capacity, agency, and increasingly the will to assert themselves on the global stage. Many of these states have the power to meaningfully shape the future of AI. There are also emerging economies that have the potential to reap the rewards of AI – if the right policies and institutions are established – and whose talent, resources, and voices are essential to ensure that the creation of a human-like intelligence benefits all of humanity.

The AI incumbents: The US & ChinaThe US and China are the world’s leading AI competitors, but they are also the most important AI collaborators. According to Stanford University’s 2023 Artificial Intelligence Index Report, despite increased geopolitical competition, the number of AI research collaborations between the two countries quadrupled between 2010 and 2021, though the rate of collaboration has slowed significantly since then, and will likely continue to do so. More so every day, AI is a critical domain in which the US and China cooperate, compete, and confront one another economically, technologically, politically, and militarily.

The great power AI competition focuses on hardware, data, software, and talent. Each country is pushing the technology further, developing AI champions, and finding the most relevant use cases and advantageous areas for AI adoption. The US and China are, in different ways, seeking to advance their absolute and relative positions, protect their interests, and secure leverage as they each follow distinct strategies.

The US is the world’s preeminent AI power, thanks to its world-leading universities and companies. Working alongside a global network of allies and partners on everything from research to export controls, Washington is concerned with keeping its advantages and accelerating the pace of domestic AI innovation. American industry leaders warn of the potential perils if the US were to “slow down American industry in such a way that China or somebody else makes faster progress.” Meanwhile, China will continue executing its long-term, state-led policies, including initiatives like “Made in China 2025” to increase self-reliance, bolster its domestic AI industry, and increase its leverage over competitors.

Today, large language models (LLMs) are the primary arena of AI innovation and competition, and countries are racing to develop more advanced and capable LLMs. In general, LLM performance improves with scale – more parameters, more and better training data, more training runs and more computation. While GPT2 boasted some 1.5 billion parameters, subsequent models have grown by orders of magnitude, with GPT4 reportedly incorporating 1 trillion such variables. The massive open data ecosystem of the internet has played a fundamental role in the development of these models. The amount of compute dedicated to training these models has also increased sharply, driven by advances in silicon innovation. Finally, breakthroughs in software and model architecture design drive and accelerate improvements.

While China had matched or exceeded the US’s historic lead in many fields of traditional AI research, the overwhelming majority of innovations in generative AI today are coming from the US, and China faces an uphill battle in training LLMs, for now.

As with past technological revolutions, the nature of different governance systems can enhance or impede progress. Open societies like the US worry about AI risks, including the accuracy of LLM outputs and hallucinations, a phenomenon wherein an LLM provides inaccurate information based on the perception of patterns that do not exist or are otherwise faulty. But they do not let those concerns halt progress. Meanwhile, closed societies, including China, have different worries, particularly about their ability to control domestic speech and content that may not be state-approved, and their capacity to advance what many analysts describe as Beijing’s “discourse power,” a way to shape global narratives. AI systems are unpredictable, and their black-box structure features inputs that are often invisible and outputs that cannot be determined by government officials and censors. These are particular concerns for closed societies, and have led the Chinese state to impose restrictions that may limit innovation, hold back incumbents, and deter new entrants and entrepreneurs from engaging with this technology.

For example, Beijing proposed new rules in April 2023 for developers and deployers of generative AI, including a requirement that “content generated using generative AI shall embody the Core Socialist Values and must not incite subversion of national sovereignty or the overturn of the socialist system.” The Party’s concern was therefore not about inaccurate information or hallucinations, but about potentially truthful outputs that may not conform to a Beijing-endorsed position. While the Chinese government has since issued somewhat less restrictive regulations, pushes for political control over technological developments highlight self-imposed challenges to AI development. As a result, Chinese LLMs are often trained on smaller, more restricted data sets than their Western counterparts. Censorship regimes may also compromise or bias access to and the production of data. And they pose even greater engineering challenges regarding moderation of non-deterministic outputs vs. democratic counterparts.

In addition to models, in recent years, the AI competition between the US and China has focused on hardware, as the clearest path to greater compute is via access to high-performance graphics processing units (GPUs). While China has a robust domestic semiconductor industry, China’s vulnerability in the “chip wars,” the competition over the microchip technologies that power AI, was exposed on October 7, 2022, by a set of US-led export controls on high-end semiconductors and related technologies, which the US coordinated with the Netherlands and Japan. These export controls follow a strategy described as “small yard, high fence,” wherein a limited number of national-security sensitive technologies are protected through strict measures.

While these US-led export controls have marked a clear turning point in US-China technology competition, there have been challenges to enforcement, including due to the need to coordinate with international partners over complex, global supply chains. To tighten enforcement, on October 17, 2023, the US released updated export controls on advanced semiconductor technology, specifically targeting chips and equipment essential for artificial intelligence development, including restrictions on high-performance chips and advanced lithography tools.

Beijing has responded to the US-led controls with its own export controls, including on critical minerals such as germanium, gallium, and more recently graphite, areas where China has a historic supply-chain advantage. More significantly, Beijing increased its focus on domestic technological development and self-reliance. As the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission reported, Chinese companies “surged their orders for foreign semiconductor manufacturing technology in 2023, capitalizing on the roughly eight-month lag between when the Dutch government announced its intent to place controls on exports to China and its implementation.”

Despite US-led export controls, China’s progress in hardware has continued, if at a slower pace. In September, the Chinese state-owned Semiconductor Manufacturing International Company (SMIC) and a Huawei subsidiary named HiSilicon demonstrated the capability to produce hardware comparable to Nvidia’s A100 chip, with the fabrication of a 7-nm chip using foreign-made equipment already present in-country. This chip is shipping in Huawei’s latest smartphone, the Mate 60 Pro, which scholar Chris Miller has described as “the most ‘Chinese’ advanced smartphone ever made” because “the phone’s primary 7-nm processor [and] many of the phone’s auxiliary chips are homegrown, including the Bluetooth, WiFi and power management chips.”

The Mate 60 Pro was a significant breakthrough that showed the shortfalls of existing export controls and the capabilities of China’s semiconductor sector. While China remains two generations behind the world’s most cutting-edge chips, its technology ecosystem is a world leader in many fields, partially due to its robust domestic industries, strengths in data, and significant domestic talent pipeline. However, serious questions remain about the depth of China’s technological ecosystem, its ability to achieve comparable results without further international imports, and its capacity to scale production at acceptable costs, given the challenges that export control impose.

The chip wars have significance not only for geopolitics, but also for global markets. They have reshaped the movement of goods and intellectual capital, and major chipmakers like Nvidia have attempted to operate within the new paradigm by releasing versions of their products targeted for Chinese markets that are as advanced as possible, given the restrictions. The results have been clear: US semiconductor exports to China dropped by 51%, from $6.4 billion to $3.1 billion, in the first eight months of 2023 compared to the same period in 2022.

Meanwhile, the US is working to friendshore and onshore semiconductor supply chains. The CHIPS and Science Act introduced $39 billion in incentives for domestic chip production, and this funding includes national-security conditions, such as restricting recipients of federal dollars from involvement in the “material expansion” of “semiconductor manufacturing capacity” in a “foreign country of concern” (e.g., China, Russia, Iran, or North Korea). Such programs aim to give the US a relative edge and, as White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan stated, “as large of a lead as possible” in critical technologies.

But leadership in AI does not come primarily from state-led initiatives. For countries to lead in AI, they need national strategies that foster and direct innovation, as well as world-leading AI companies and research institutions. The generative AI ecosystem will empower incumbent enterprises and also likely define the next generation of Big Tech companies. Private AI investment globally is considerable and growing, and is forecast to increase to more than $160 billion by 2025, according to Goldman Sachs Research. However, sustained growth and innovation requires a system that promotes property rights and entrepreneurship, and that provides predictable rules of the road to startups and mega-cap technology companies alike. China’s crackdown on technology companies, dating back to at least 2020, and dramatic shifts like the cancellation of a leading Chinese technology company’s IPO, increases uncertainty in the non-state sector, decreasing the dynamism of China’s technology ecosystem.

The US is the preeminent AI power today. But the US-China technology competition is far from settled. We will see evolving strategies of techno-economic statecraft from both sides. In the past, China has shown a remarkable ability to overcome economic, geopolitical, and structural challenges to its position, and Beijing will continue to strive do so, as the Mate 60 Pro demonstrated. There are also potential paths of chip research and development, including advanced packaging, that provide new trajectories for improvement. For AI models, it is possible that entirely novel architectures could emerge that are not as dependent on the chips the West dominates today. Even if China remains the world’s number-two AI power, China will remain a formidable competitor to the US and to the US-led technology ecosystem.

For the foreseeable future, we expect geopolitics to increasingly driving economic decision-making in Washington and Beijing, and in capitals around the world. The US, China, and other countries are using new and old tools to advance political objectives through economic means. The table below outlines a few of the most prominent techno-economic tools shaping technology competition.

READ MORE:

https://www.goldmansachs.com/insights/articles/the-generative-world-order-ai-geopolitics-and-power

READ FROM TOP.

YOURDEMOCRACY.NET RECORDS HISTORY AS IT SHOULD BE — NOT AS THE WESTERN MEDIA WRONGLY REPORTS IT — SINCE 2005.

Gus Leonisky

POLITICAL CARTOONIST SINCE 1951.

METHINKS THAT RUSSIA IS QUIETLY DOING ITS AI "BEHIND CLOSED DOORS"..... MEANWHILE EUROPE IS PEDALLING...