Search

Recent comments

- crummy....

11 hours 58 min ago - RC into A....

13 hours 51 min ago - destabilising....

14 hours 55 min ago - lowe blow....

15 hours 27 min ago - names....

16 hours 4 min ago - sad sy....

16 hours 29 min ago - terrible pollies....

16 hours 39 min ago - illegal....

17 hours 51 min ago - sinister....

20 hours 13 min ago - war council.....

1 day 5 hours ago

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

upon my soul .....

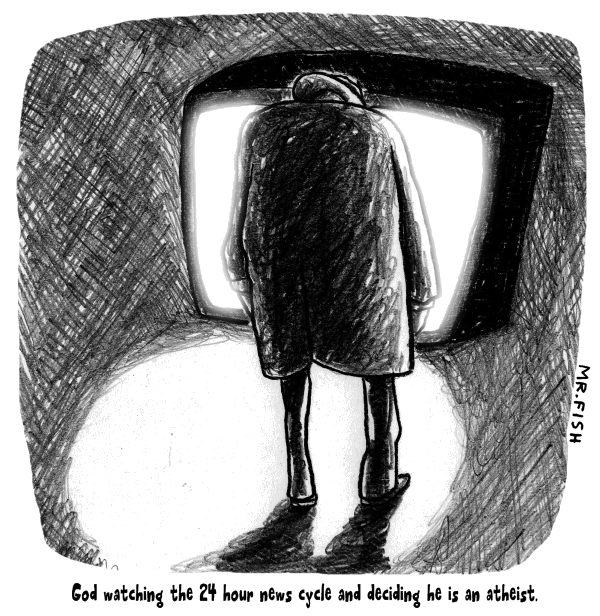

"Does God exist?" is a valid and relevant question. Here are my top reasons why the answer is a resounding, "No."

The following is an excerpt from Why Are You Atheists So Angry? 99 Things That Piss Off the Godless by Greta Christina. The book is available electronically on Kindle, Nook, and soon in print.

"But just because religion has done some harm -- that doesn't mean it's mistaken! Sure, people have done terrible things in God's name. That doesn't mean God doesn't exist!"

Yup. If you're arguing that -- you're absolutely right. And the question of whether religion is true or not is important. It's not the main point of this book: if you want more thorough arguments for why God doesn't exist, by me or other writers, check out the Resource Guide at the end of this book. But "Does God exist?" is a valid and relevant question. Here are my Top Ten reasons why the answer is a resounding, "No."

1: The consistent replacement of supernatural explanations of the world with natural ones.

When you look at the history of what we know about the world, you see a noticeable pattern. Natural explanations of things have been replacing supernatural explanations of them. Like a steamroller. Why the Sun rises and sets. Where thunder and lightning come from. Why people get sick. Why people look like their parents. How the complexity of life came into being. I could go on and on.

All these things were once explained by religion. But as we understood the world better, and learned to observe it more carefully, the explanations based on religion were replaced by ones based on physical cause and effect. Consistently. Thoroughly. Like a steamroller. The number of times that a supernatural explanation of a phenomenon has been replaced by a natural explanation? Thousands upon thousands upon thousands.

Now. The number of times that a natural explanation of a phenomenon has been replaced by a supernatural one? The number of times humankind has said, "We used to think (X) was caused by physical cause and effect, but now we understand that it's caused by God, or spirits, or demons, or the soul"?

Exactly zero.

Sure, people come up with new supernatural "explanations" for stuff all the time. But explanations with evidence? Replicable evidence? Carefully gathered, patiently tested, rigorously reviewed evidence? Internally consistent evidence? Large amounts of it, from many different sources? Again -- exactly zero.

Given that this is true, what are the chances that any given phenomenon for which we currently don't have a thorough explanation -- human consciousness, for instance, or the origin of the Universe -- will be best explained by the supernatural?

Given this pattern, it's clear that the chances of this are essentially zero. So close to zero that they might as well be zero. And the hypothesis of the supernatural is therefore a hypothesis we can discard. It is a hypothesis we came up with when we didn't understand the world as well as we do now... but that, on more careful examination, has never once been shown to be correct.

If I see any solid evidence to support God, or any supernatural explanation of any phenomenon, I'll reconsider my disbelief. Until then, I'll assume that the mind-bogglingly consistent pattern of natural explanations replacing supernatural ones is almost certain to continue.

(Oh -- for the sake of brevity, I'm generally going to say "God" in this chapter when I mean "God, or the soul, or metaphysical energy, or any sort of supernatural being or substance." I don't feel like getting into discussions about, "Well, I don't believe in an old man in the clouds with a white beard, but I believe..." It's not just the man in the white beard that I don't believe in. I don't believe in any sort of religion, any sort of soul or spirit or metaphysical guiding force, anything that isn't the physical world and its vast and astonishing manifestations.

2: The inconsistency of world religions.

If God (or any other metaphysical being or beings) were real, and people were really perceiving him/ her/ it/ them, why do these perceptions differ so wildly?

When different people look at, say, a tree, we more or less agree about what we're looking at: what size it is, what shape, whether it currently has leaves or not and what color those leaves are, etc. We may have disagreements regarding the tree -- what other plants it's most closely related to, where it stands in the evolutionary scheme, should it be cut down to make way for a new sports stadium, etc. But unless one of us is hallucinating or deranged or literally unable to see, we can all agree on the tree's basic existence, and the basic facts about it.

This is blatantly not the case for God. Even among people who do believe in God, there is no agreement about what God is, what God does, what God wants from us, how he acts or doesn't act on the world, whether he's a he, whether there's one or more of him, whether he's a personal being or a diffuse metaphysical substance. And this is among smart, thoughtful people. What's more, many smart, thoughtful people don't even think God exists.

And if God existed, he'd be a whole lot bigger, a whole lot more powerful, with a whole lot more effect in the world, than a tree. Why is it that we can all see a tree in more or less the same way, but we don't see God in even remotely the same way?

The explanation, of course, is that God does not exist. We disagree so radically over what he is because we aren't perceiving anything that's real. We're "perceiving" something we made up; something we were taught to believe; something that the part of our brain that's wired to see pattern and intention, even when none exists, is inclined to see and believe.

3: The weakness of religious arguments, explanations, and apologetics.

I have seen a lot of arguments for the existence of God. And they all boil down to one or more of the following: The argument from authority. (Example: "God exists because the Bible says God exists.") The argument from personal experience. (Example: "God exists because I feel in my heart that God exists.") The argument that religion shouldn't have to logically defend its claims. (Example: "God is an entity that cannot be proven by reason or evidence.") Or the redefining of God into an abstract principle... so abstract that it can't be argued against, but also so abstract that it scarcely deserves the name God. (Example: "God is love.")

And all these arguments are ridiculously weak.

Sacred books and authorities can be mistaken. I have yet to see a sacred book that doesn't have any mistakes. (The Bible, to give just one example, is shot full of them.) And the feelings in people's hearts can definitely be mistaken. They are mistaken, demonstrably so, much of the time. Instinct and intuition play an important part in human understanding and experience... but they should never be treated as the final word on a subject. I mean, if I told you, "The tree in front of my house is 500 feet tall with hot pink leaves," and I offered as a defense, "I know this is true because my mother/ preacher/ sacred book tells me so"... or "I know this is true because I feel it in my heart"... would you take me seriously?

Some people do try to prove God's existence by pointing to evidence in the world. But that evidence is inevitably terrible. Pointing to the perfection of the Bible as a historical and prophetic document, for instance... when it so blatantly is nothing of the kind. Or pointing to the fine-tuning of the Universe for life... even though this supposedly perfect fine-tuning is actually pretty crappy, and the conditions that allow for life on Earth have only existed for the tiniest fragment of the Universe's existence and are going to be boiled away by the Sun in about a billion years. Or pointing to the complexity of life and the world and insisting that it must have been designed... when the sciences of biology and geology and such have provided far, far better explanations for what seems, at first glance, like design.

As to the argument that "We don't have to show you any reason or evidence, it's unreasonable and intolerant for you to even expect that"... that's conceding the game before you've even begun. It's like saying, "I know I can't make my case -- therefore I'm going to concentrate my arguments on why I don't have to make my case in the first place." It's like a defense lawyer who knows their client is guilty, so they try to get the case thrown out on a technicality.

Ditto with the "redefining God out of existence" argument. If what you believe in isn't a supernatural being or substance that has, or at one time had, some sort of effect on the world... well, your philosophy might be an interesting one, but it is not, by any useful definition of the word, religion.

Again: If I tried to argue, "The tree in front of my house is 500 feet tall with hot pink leaves -- and the height and color of trees is a question that is best answered with personal faith and feeling, not with reason or evidence"... or, "I know this is true because I am defining '500 feet tall and hot pink' as the essential nature of tree-ness, regardless of its outward appearance"... would you take me seriously?

4: The increasing diminishment of God.

This is closely related to #1 (the consistent replacement of supernatural explanations of the world with natural ones). But it's different enough to deserve its own section.

When you look at the history of religion, you see that the perceived power of God has been diminishing. As our understanding of the physical world has increased -- and as our ability to test theories and claims has improved -- the domain of God's miracles and interventions, or other supposed supernatural phenomena, has consistently shrunk.

Examples: We stopped needing God to explain floods... but we still needed him to explain sickness and health. Then we didn't need him to explain sickness and health... but we still needed him to explain consciousness. Now we're beginning to get a grip on consciousness, so we'll soon need God to explain... what?

Or, as writer and blogger Adam Lee so eloquently put it in his Ebon Musings website, "Where the Bible tells us God once shaped worlds out of the void and parted great seas with the power of his word, today his most impressive acts seem to be shaping sticky buns into the likenesses of saints and conferring vaguely-defined warm feelings on his believers' hearts when they attend church."

This is what atheists call the "god of the gaps." Whatever gap there is in our understanding of the world, that's what God is supposedly responsible for. Wherever the empty spaces are in our coloring book, that's what gets filled in with the blue crayon called God.

But the blue crayon is worn down to a nub. And it's never turned out to be the right color. And over and over again, throughout history, we've had to go to great trouble to scrape the blue crayon out of people's minds and replace it with the right color. Given this pattern, doesn't it seem that we should stop reaching for the blue crayon every time we see an empty space in the coloring book?

5: The fact that religion runs in families.

The single strongest factor in determining what religion a person is? It's what religion they were brought up with. By far. Very few people carefully examine all the available religious beliefs -- or even some of those beliefs -- and select the one they think most accurately describes the world. Overwhelmingly, people believe whatever religion they were taught as children.

Now, we don't do this with, for instance, science. We don't hold on to the Steady State theory of the Universe, or geocentrism, or the four bodily humours theory of illness, simply because it's what we were taught as children. We believe whatever scientific understanding is best supported by the best available evidence at the time. And if the evidence changes, our understanding changes. (Unless, of course, it's a scientific understanding that our religion teaches is wrong...)

Even political opinions don't run in families as stubbornly as religion. Witness the opinion polls that show support of same-sex marriage increasing with each new generation. Political beliefs learned from youth can, and do, break down in the face of the reality that people see every day. And scientific theories do this, all the time, on a regular basis.

This is emphatically not the case with religion.

Which leads me to the conclusion that religion is not a perception of a real entity. If it were, people wouldn't just believe whatever religion they were taught as children, simply because it was what they were taught as children. The fact that religion runs so firmly in families strongly suggests that it is not a perception of a real phenomenon. It is a dogma, supported and perpetuated by tradition and social pressure -- and in many cases, by fear and intimidation. Not by reality.

6: The physical causes of everything we think of as the soul.

The sciences of neurology and neuropsychology are in their infancy. But they are advancing by astonishing leaps and bounds, even as we speak. And what they are finding -- consistently, thoroughly, across the board -- is that, whatever consciousness is, it is inextricably linked to the brain.

Everything we think of as the soul -- consciousness, identity, character, free will -- all of that is powerfully affected by physical changes to the brain and body. Changes in the brain result in changes in consciousness... sometimes so drastically, they make a personality unrecognizable. Changes in consciousness can be seen, with magnetic resonance imagery, as changes in the brain. Illness, injury, drugs and medicines, sleep deprivation, etc.... all of these can make changes to the supposed "soul," both subtle and dramatic. And death, of course, is a physical change that renders a person's personality and character, not only unrecognizable, but non-existent.

So the obvious conclusion is that consciousness and identity, character and free will, are products of the brain and the body. They're biological processes, governed by laws of physical cause and effect. With any other phenomenon, if we can show that physical forces and actions produce observable effects, we think of that as a physical phenomenon. Why should the "soul" be any different?

What's more, the evidence supporting this conclusion comes from rigorously-gathered, carefully-tested, thoroughly cross-checked, double-blinded, placebo- controlled, replicated, peer-reviewed research. The evidence has been gathered, and continues to be gathered, using the gold standard of scientific evidence: methods specifically designed to filter out biases and cognitive errors as much as humanly possible. And it's not just a little research. It's an enormous mountain of research... a mountain that's growing more mountainous every day.

The hypothesis of the soul, on the other hand, has not once in all of human history been supported by good, solid scientific evidence. That's pretty surprising when you think about it. For decades, and indeed centuries, most scientists had some sort of religious beliefs, and most of them believed in the soul. So a great deal of early science was dedicated to proving the soul's existence, and discovering and exploring its nature. It wasn't until after decades upon decades of fruitless research in this area that scientists finally gave it up as a bad job, and concluded, almost unanimously, that the reason they hadn't found a soul was that there was no such thing.

Are there unanswered questions about consciousness? Absolutely. Tons of them. No reputable neurologist or neuropsychologist would say otherwise. But think again about how the history of human knowledge is the history of supernatural explanations being replaced by natural ones... with relentless consistency, again, and again, and again. There hasn't been a single exception to this pattern. Why would we assume that the soul is going to be that exception? Why would we assume that this gap in our knowledge, alone among all the others, is eventually going to be filled with a supernatural explanation? The historical pattern doesn't support it. And the evidence doesn't support it. The increasingly clear conclusion of the science is that consciousness is a product of the brain. Period.

7: The complete failure of any sort of supernatural phenomenon to stand up to rigorous testing.

Not all religious and spiritual beliefs make testable claims. But some of them do. And in the face of actual testing, every one of those claims falls apart like Kleenex in a hurricane.

Whether it's the power of prayer, or faith healing, or astrology, or life after death: the same pattern is seen. Whenever religious and supernatural beliefs have made testable claims, and those claims have been tested -- not half-assedly tested, but really tested, using careful, rigorous, double-blind, placebo-controlled, replicated, etc. etc. etc. testing methods -- the claims have consistently fallen apart. Occasionally a scientific study has appeared that claimed to support something supernatural... but more thorough studies have always refuted them. Every time.

I'm not going to cite each one of these tests, or even most of them. This chapter is already long as it is. Instead, I'll encourage you to spend a little time on the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry and Skeptical Inquirer websites. You'll see a pattern so consistent it boggles the mind: Claimants insist that Supernatural Claim X is real. Supernatural Claim X is subjected to careful testing, applying the standard scientific methods used in research to screen out bias and fraud. Supernatural Claim X is found to hold about as much water as a sieve. (And claimants, having agreed beforehand that the testing method is valid, afterwards insist that it wasn't fair.)

And don't say, "Oh, the testers were biased." That's the great thing about the scientific method. It's designed to screen out bias, as much as is humanly possible. When done right, it will give you the right answer, regardless of the bias of the people doing the testing.

And I want to repeat an important point about the supposed anti-religion bias in science. In the early days of science and the scientific method, most scientists did believe in God, and the soul, and the metaphysical. In fact, many early science experiments were attempts to prove the existence of these things, and discover their true natures, and resolve the squabbles about them once and for all. It was only after decades of these experiments failing to turn up anything at all that the scientific community began -- gradually, and very reluctantly -- to give up on the idea.

Supernatural claims only hold up under careless, casual examination. They are supported by wishful thinking, and confirmation bias (i.e., our tendency to overemphasize evidence that supports what we believe and to discard evidence that contradicts it), and our poor understanding and instincts when it comes to probability, and our tendency to see pattern and intention even when none exists, and a dozen other forms of cognitive bias and weird human brain wiring. When studied carefully, under conditions specifically designed to screen these things out, the claims vanish like the insubstantial imaginings they are.

8: The slipperiness of religious and spiritual beliefs.

Not all religious and spiritual beliefs make testable claims. Many of them have a more "saved if we do, saved if we don't" quality. If things go the believer's way, it's a sign of God's grace and intervention; if they don't, then God moves in mysterious ways, and maybe he has a lesson to teach that we don't understand, and it's not up to us to question his will. No matter what happens, it can be twisted to prove that the belief is right.

That is a sure sign of a bad argument.

Here's the thing. It is a well-established principle in the philosophy of science that, if a theory can be supported no matter what possible evidence comes down the pike, it is useless. It has no power to explain what's already happened, or to predict what will happen in the future. The theory of gravity, for instance, could be disproven by things suddenly falling up; the theory of evolution could be disproven by finding rabbits in the pre-Cambrian fossil layer. These theories predict that those things won't happen; if they do, the theories go poof. But if your theory of God's existence holds up no matter what happens -- whether your friend with cancer gets better or dies, whether natural disasters strike big sinful cities or small God-fearing towns -- then it's a useless theory, with no power to predict or explain anything.

What's more, when atheists challenge theists on their beliefs, the theists' arguments shift and slip around in an annoying "moving the goalposts" way. Hard-line fundamentalists, for instance, will insist on the unchangeable perfect truth of the Bible; but when challenged on its specific historical or scientific errors, they insist that you're not interpreting those passages correctly. (If the book needs interpreting, then how perfect can it be?)

And progressive ecumenical believers can be unbelievably slippery about what they do and don't believe. Is God real, or a metaphor? Does God intervene in the world, or doesn't he? Do they even believe in God, or do they just choose to act as if they believe because they find it useful? Debating with a progressive believer is like wrestling with a fish: the arguments aren't very powerful, but they're slippery, and they don't give you anything firm to grab onto.

Once again, that's a sure sign of a bad argument. If you can't make your case and then stick by it, or modify it, or let it go... then you don't have a good case. (And if you're making any version of the "Shut up, that's why" argument -- arguing that it's intolerant to question religious beliefs, or that letting go of doubts about faith makes you a better person, or that doubting faith will get you tortured in Hell, or any of the other classic arguments intended to quash debate rather than address it -- that's a sure sign that your argument is in the toilet.)

9: The failure of religion to improve or clarify over time.

Over the years and decades and centuries, our understanding of the physical world has grown and clarified by a ridiculous amount. We understand things about the Universe that we couldn't have imagined a thousand years ago, or a hundred, or even ten. Things that make your mouth gape with astonishment just to think about.

And the reason for this is that we came up with an incredibly good method for sorting out good ideas from bad ones. We came up with the scientific method, a self-correcting method for understanding the physical world: a method which -- over time, and with the many fits and starts that accompany any human endeavor -- has done an astonishingly good job of helping us perceive and understand the world, predict it and shape it, in ways we couldn't have imagined in decades and centuries past. And the scientific method itself is self-correcting. Not only has our understanding of the natural world improved dramatically: our method for understanding it is improving as well.

Our understanding of the supernatural world? Not so much.

Our understanding of the supernatural world is in the same place it's always been: hundreds and indeed thousands of sects, squabbling over which sacred texts and spiritual intuitions are the right ones. We haven't come to any consensus about which religion best understands the supernatural world. We haven't even come up with a method for making that decision. All anyone can do is point to their own sacred text and their own spiritual intuition. And around in the squabbling circle we go.

All of which points to religion, not as a perception of a real being or substance, but as an idea we made up and are clinging to. If religion were a perception of a real being or substance, our understanding of it would be sharpening, clarifying, being refined. We'd have better prayer techniques, more accurate prophecies, something. Anything but people squabbling with greater or lesser degrees of rancor, and nothing to back up their belief.

10: The complete lack of solid evidence for God's existence.

This is probably the best argument I have against God's existence: There's no evidence for it. No good evidence, anyway. No evidence that doesn't just amount to opinion and tradition and confirmation bias and all the other stuff I've been talking about. No evidence that doesn't fall apart upon close examination.

And in a perfect world, that should have been the only argument I needed. In a perfect world, I shouldn't have had to spend a month and a half collating and summarizing the reasons I don't believe in God, any more than I would have for Zeus or Quetzalcoatl or the Flying Spaghetti Monster. As thousands of atheists before me have pointed out: It is not up to us to prove that God does not exist. It is up to theists to prove that he does.

In a comment on my blog, arensb made a point on this topic that was so insightful, I'm still smacking myself on the head for not having thought of it myself. I was writing about how believers get upset at atheists when we reject religion after hearing 876,363 bad arguments for it, and how believers react to this by saying, "But you haven't considered Argument #876,364! How can you be so close-minded?" And arensb said:

"If, in fact, it turns out that argument #876,364 is the one that will convince you, WTF didn't the apologists put it in the top 10?"

Why, indeed?

If there's an argument for religion that's convincing -- actually convincing, convincing by means of something other than authority, tradition, personal intuition, confirmation bias, fear and intimidation, wishful thinking, or some combination of the above -- wouldn't we all know about it?

Wouldn't it have spread like wildfire? Wouldn't it be the Meme of All Memes? I mean, we all saw that Simon's Cat video within about two weeks of it hitting the Internet. Don't you think that the Truly Excellent Argument for God's Existence would have spread even faster, and wider, than some silly cartoon cat video?

If the arguments for religion are so wonderful, why are they so unconvincing to anyone who doesn't already believe?

And why does God need arguments, anyway? Why does God need people to make his arguments for him? Why can't he just reveal his true self, clearly and unequivocally, and settle the question once and for all? If God existed, why wouldn't it just be obvious?

It is not up to atheists to prove that God does not exist. It is up to believers to prove that he does. And in the absence of any good, solid evidence or arguments in favor of God's existence -- and in the presence of a whole lot of solid arguments against it -- I will continue to be an atheist. God almost certainly does not exist, and it's completely reasonable to act as if he doesn't.

- By John Richardson at 1 Apr 2012 - 6:59am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

the wars disguised as peace...

...

In much the same way that rich societies exported their pollution to developing countries, the societies of the highly-developed world exported their conflicts. They were at war with one another the entire time - not only in Indo-China but in other parts of Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. The Korean war, the Chinese invasion of Tibet, British counter-insurgency warfare in Malaya and Kenya, the abortive Franco-British invasion of Suez, the Angolan civil war, decades of civil war in the Congo and Guatemala, the Six Day War, the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956 and of Czechoslovakia in 1968, the Iran-Iraq war and the Soviet-Afghan war - these are only some of the armed conflicts through which the great powers pursued their rivalries while avoiding direct war with each other. When the end of the Cold War removed the Soviet Union from the scene, war did not end. It continued in the first Gulf war, the Balkan wars, Chechnya, the Iraq war and in Afghanistan and Kashmir, among other conflicts.

http://www.abc.net.au/religion/articles/2012/03/28/3465381.htm