Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

hey wayne ....

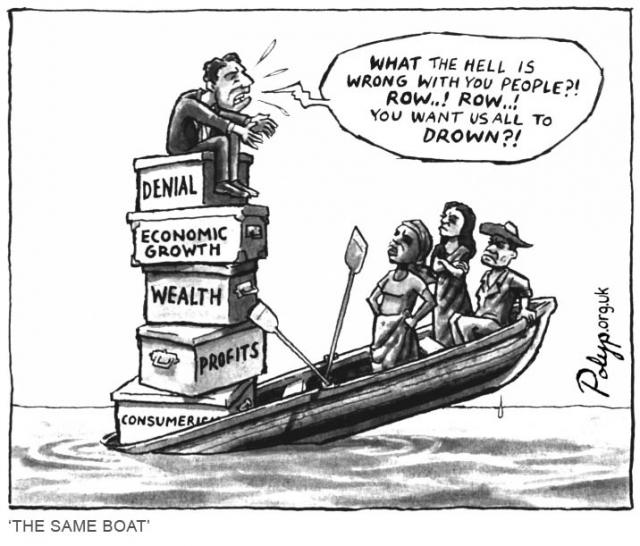

For years, economists have posited that prosperity requires growth, with environmental damage as the regrettable but unavoidable consequence. A growing number of critics are now challenging this equation, though, calling for a radical revamping of the economic system.

Harald Welzer's career as a critic of growth began with a few simple reflections. Just how progressive is it, he asked himself, when millions of hectares of land are used elsewhere in the world so that we keep down the cost of meat? How modern is it when producing a kilogram of salmon in a supposedly sustainable way requires feeding the fish five to six kilograms (11 to 13 pounds) of other types of fish?

If everyone used up as much space and resources as we do, says the 54-year-old Berlin-based social psychologist, we would need three earths. In Welzer's eyes, this can hardly be called progress.

All of this made Welzer so angry that he wrote a book critical of equating this sort of progress with growth. The ruling class of economists, who he characterizes as "disdainers of reality" and "proponents of a world essentially limited by consumption," is responsible for compulsively tying these two concepts together, he argues. His treatise, "Selbst denken" ("Thinking for Ourselves"), is a manual for phasing out the "totalitarian consumerism" that gives people desires that, until recently, they didn't even suspect they would ever have.

Until a few months ago, Welzer specialized in studying the psyche of Nazi criminals. He has also written about climate wars. His current bestseller, "Selbst denken," has now made him the figurehead of a movement that radically questions the growth model of the Western economy.

Welzer was also recently named a professor in transformation design at the University of Flensburg, in northern Germany. When a local journalist asked him what transformation design is, he replied: "We don't exactly know yet ourselves." But the goal of the discipline, he added, is to counter the "systematic scam" created by an industry that produces things that break unnecessarily or are hardly capable of being repaired. Welzer wants to "design corridors" in which companies would be given time to transform faceless, no-name products into durable products with an origin and a history.

Economists have largely disregarded the environmental consequences of growth. For them, the key benchmark of prosperity is gross domestic product (GDP), the sum of all products and services produced in a given country. However, GDP does not factor in the overexploitation of resources, the destruction of biological diversity, air pollution, noise, the expansion of impervious surfaces known as soil sealing, and the poisoning of groundwater.

But for many people, a wealth model built on chronic growth is no longer a desirable goal. They are deciding to opt out of this model by establishing "repair cafés" or "transition towns," communities that try to run things differently at the local level. But doubts about the growth dogma are even beginning to creep into politics. For instance, German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble, a member of Chancellor Angela Merkel's center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU), recently argued that Western countries should "espouse limiting economic growth" at home.

But can there be prosperity without growth and growth without environmental damage? How can jobs be preserved in a stagnating or even a shrinking economy? How can a government service its debts in such an economy, especially as the population shrinks?

The 'Culture of Enough'

The German parliamentary commission on growth, prosperity and quality of life spent two years trying to find answers to these questions. Two weeks ago, the commission presented its 1,000-page final report. In the end, it was as far removed from a consensus as it was at the beginning.

Faith in never-ending growth has long had its critics. But many found warnings like those coming from the Club of Rome, especially in its study on the "Limits of Growth," to be too alarmist. Nevertheless, the financial crisis has brought renewed misgivings about the system. One of the first to point the way to an alternative was British economist Tim Jackson. In his 2009 book "Prosperity Without Growth," he outlined a "coherent ecological macroeconomics" based on a "fixed" economy with strict upper limits on emissions and resources.

Many in the British political world have viewed Jackson, an expert with the UK's Sustainable Development Commission, as a bit of an oddball. Hostile government tax officials wondered whether Jackson was proposing that we all go back to living in caves. A professor at the University of Surrey, near London, Jackson had had the audacity to paint capitalism as a faulty system, as a gluttony machine that constantly needs new supplies of people prepared to resolutely continue consuming goods and services.

And when consumers lose their taste for new things, Jackson argues, our system has plenty of shrewd advertisers, marketers and investors to persuade us "to spend money we don't have on things that we don't need to create impressions that won't last on people we don't care about." Jackson's book, already translated into 15 languages, became a bestseller in the new "culture of enough."

"It's time to change the channel," says Welzer, the German growth critic. He is giving a talk in a large lecture hall at the University of Flensburg, and the room is so full that even most of the steps along the side are occupied.

"We apply the old recipes, which is typical for societies that come under stress," he says. "They recognize that resources are dwindling, and yet they intensify their exploitation and accelerate their own demise." He sees no better example of this than the way we treat our resources. "Peak oil? Let's drill deeper! Natural gas bottlenecks? Let's use chemicals to pump it out of the earth! Cash-strapped financial markets? Let's flood them!"

According to Niko Paech, a 52-year-old economics professor in the northern German city of Oldenburg, we continue to apply these remedies until GDP is back on track, even in the midst of a crisis. But, he adds, treating GDP as a measure of the prosperity of modern societies is downplaying the problem and is "a measure of environmental destruction."

Paech advocates a shrinking economy and preaches a new frugality. He has been wearing his striped brown sport coat for 25 years, and no matter where he is invited, he always takes his bike or the train. In fact, he has only flown once in his life.

Paech attacks what he calls our "autistic faith in progress." He is not interested in criticizing a few greedy executives for destroying a supposedly good system. For Paech, the system itself is broken, and instead of repairing it, he wants to rebuild it from the ground up. He no longer believes in reconciliation between the environment and the economy, and in the notion that a level of prosperity achieved through credit can simply be continued through green growth. And unlike many members of the environmentalist Green Party, Paech adds, he is "extremely conservative."

His message is simple: that we should be giving up and sharing some of our wealth. The labor market he envisions is full of thriving repair and maintenance shops. He wants to see our society become more civilized with less: less material, less energy, less waste and less pollution. He also believes that resources should be managed more effectively. We should produce the kind of clothing, he argues, that can be handed down from one generation to the next instead of throwing things away after wearing them just a few times.

The post-growth theorist explained to a perplexed journalist for the website of Bild, Germany's top-selling tabloid newspaper, that Germans are not role models when it comes to environmental protection because they have merely outsourced their dirty production. For Paech, wealth that can no longer be stabilized without growth is merely "the result of comprehensive environmental depredation."

The most important argument against growth skeptics like Paech is technology. Influential US economist Julian Simon, for example, predicted that technological advancements could bring us 7 billion more years of growth. The hope is that better and more environmentally friendly products will essentially eliminate the limits on growth. For example, the PR strategists of the Initiative for a New Social Market Economy (INSM), a German umbrella lobbying group supported by free-market-inclined politicians of all stripes, use the slogan "Less CO2 needs more growth."

But disconnecting growth from more consumption and environmental degradation is still just a dream. According to a study by the parliamentary commission on growth, prosperity and quality of life, which summarizes the current state of research in the field, growth with declining absolute resource consumption currently exists "as good as nowhere" in the world.

There are now alternative methods to measure growth, such as the National Prosperity Index developed by Hans Diefenbacher, an economist in the western German city of Heidelberg. He simply treats the negative impacts of economic activity as a reduction in our welfare. So far, his work has been largely ignored. But now even the divided parliamentary growth commission referred to his model in its final report, in which it recommended a new way of measuring growth, using an indicator called "W3." This method would not only provide information on wealth, but also on social matters, economic participation and the environment.

Leading 'A Subversive Double Existence'

But can an economy without growth truly exist? The question gives rise to great scepticism, as it does on an evening in the back room of a bar in the northern German city-state of Bremen. Niko Paech is talking to members of the Catholic Guild of St. Ansgar, a group of highly educated retirees who are relentless in their questioning.

How can you pay for our social systems when people are working 20-hour weeks, they ask? But we already can't pay for those structures today, Paech replies. In his system for the future, he explains, people would lead a sort of "subversive double existence." They would share and recycle, thereby outsmarting an industry geared toward nonstop renewal. People would only work 20 hours a week, but they would also have 20 hours of "market-free" time to provide for themselves.

But such slimmed-down jobs would hardly be enough for many people, says an older man. He hears that a lot, says Paech, especially when he speaks at union functions, where he is routinely grilled by his audience. Besides, says the economist, all the hype about jobs in our supposed knowledge society is in fact questionable. "What exactly are we doing?" he asks. "As we anxiously invoke competitiveness, we train younger and younger delegators with touchscreens to manage the dirty work, forcing Indians to whom the work is being outsourced halfway around the world to work extra hours so that we'll continue to be flooded with consumer goods." By now, some of his listeners are nodding in agreement.

Paech recently spoke at an event sponsored by Volkswagen, the German automotive giant. "I was in the lion's den, being showered with malice," he says. At a certain point, he asked what the workers did during the economic crisis, when so many saw their hours reduced under theKurzarbeit program, the "short-time work" program that the German government used during the crisis to avoid layoffs by encouraging companies to reduce workers' hours while making up for some of the workers' lost salaries and benefits itself. "We worked in the garden, did things in the neighborhood and fixed things," they told Paech.

Translated from the German by Christopher Sultan

Part 1: Rogue Economists Champion Prosperity without Growth

Part 2: Preaching a New Frugality

Less Is More: Rogue Economists Champion Prosperity Without Growth

- By John Richardson at 3 May 2013 - 6:56pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

11 hours 29 min ago

11 hours 27 min ago

12 hours 29 min ago

16 hours 34 min ago

20 hours 20 min ago

20 hours 23 min ago

20 hours 26 min ago

1 day 10 hours ago

1 day 10 hours ago

1 day 11 hours ago