Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

political cartels ...

from Independent Australia …..

Labor’s aborted secret deal with the Coalition over public funding – hard on the heels of one of the meanest pre-election budgets ever - has left the major parties looking grubby and opportunistic. With palpable distrust of politicians at an all time high, this cynical bid to bolster their hold on power via the public purse has renewed accusations of “cartel” behaviour.

Whilst it’s true every sitting member would have received the same funding under the aborted bill, on a per vote basis, the major haul would have accrued to the ALP and the Liberal Party.

In an interview on ABC’s AM on 29 May, (the day before opposition leader, Tony Abbott, declared the bill “dead”), Independent MP, Tony Windsor, went to the heart of what he saw at stake - our democracy:

“If people out there have some concern about their democracy - and I think they should start to get a little bit concerned about this particular issue, because all this is doing is locking in the two giants, the two major parties, so that they have this massive advantage over anybody else who wants to enter the playing field. That’s what it’s about. They’re quite comfortable having both sides of the tennis court occasionally but they don’t want other players in the pack. So that’s what this is all about.”

Similar sentiments were voiced by Independent MP Rob Oakeshott on ABC’s World Today:

People aren’t angry, people aren’t disappointed; they’re ashamed of this attempt at so-called political reform that looks like cartel behaviour and collusion.

A “cartel party” is a party that deals itself resources of the state to maintain its powerful position within the political system. The emergence of the cartel party in Western Europe was first identified by Katz and Mair in the 1990s. Like commercial cartels, major political parties colluded by employing the resources of the state to ensure their own collective survival. Election campaigns were:

‘…capital-intensive, professionalized and centralized, and are organized on the basis of a strong reliance on the state for financial subventions and for other benefits and privileges.’

Sound familiar?

The transition of the two major parties from mass membership models to cartels for the elite has disenfranchised party members from the political process. The steady disengagement from their membership base has seen valuable ideas crucial to problem-solving and policy-making forfeited.

As a result, the public feels our politicians no longer represent its interests but are held captive by powerful factions, unions, lobbyists and vested interests, or - in some cases - powerful foreign interests such as the United States. The Gillard government’s abandonment of Julian Assange flies in the face of the wishes of Australians who poll after poll have shown they want the government to do more. As there’s little hope of an Abbott government stepping up, it is left to the Greens as the public’s only voice.

It’s not easy to identify with politicians whose professional experience is largely limited to running unions or working in a law office. Many have made a career out of simply being a professional politician. Charismatic leaders used to help grow membership. But the love-ins of the kind we saw in the early days of Gough are a thing of the past. Never have the leaders of the two major parties been more unpopular, nor party membership so low.

Is the cartelization of our major parties a threat to democracy? How seriously should we take Tony Windsor’s and Rob Oakeshott’s concerns?

Professor Ian Marsh has been a prolific contributor to public discussion about the role of government and was former Research Director of the Liberal Party of Australia. As editor of Australian Political Parties in Transition - essential reading for anyone seriously interested in Australian politics - he examines the contributions by some of Australian’s leading academics on the evolution of the Australian party system to the cartels of today.

That isn’t to say that all political pundits and analysts agree with his findings. Professor Wayne Errington from University of Adelaide and Professor Narelle Miragliotta from Monash University in their paper ‘Adversarial Politics and Cartelization in Australia’, contend that adversarial competition between our two largest parties can slow down the process of cartelization. Errington and Miragliotta also believe the real motivation of political parties seeking inclusion in the Constitution is less to do with imposing fetters on their operations than protecting their interests in the event of a Senate vacancy caused by the death or resignation of one of their members.

Marsh, on weighing up the evidence on the other hand, says the notion of a cartel model that dominant producers (in this case political parties) will conspire to protect their position and block new entrants is ‘older even that Adam Smith‘.

Marsh divides the four phases of Australia’s party system history by differentiating organizational and/or ideological changes.

The first is the “party-based system”, which started with the Labor Party in 1891 and consolidated with the formation of the Liberal Party in 1944.

The second phase is what Marsh refers to as the “golden age” from 1944 to 1972 when mass membership of the two parties dominated the political system.

This was succeeded by the third, “catch-all” phase that lasted until 1983. Inspired by social movements unrelated to any socio-economic class, both parties sought to broaden their base by campaigning on issues such as equality of women, saving the environment, gay and indigenous rights and multiculturalism.

Significantly at the time, and paralleling the rise of social movements, was the emergence of the social counter-movement - neo-liberalism.

The fourth phase, post 1983, is when cartelization of Australian politics began. It was the year that Labor was elected and along with the new Hawke-Keating government (1983-1991) came a new bipartisan economic agenda. Former government economics adviser and now Fairfax economics columnist, Dr Lindy Edwards, argues that neo-liberalism was actually kick-started by the former Labor government when Whitlam cut tariffs by 25 per cent.

What followed was one of the most profound shifts in Australia’s economy policy ever witnessed. The economic reforms underpinned Australia’s flexibility to withstand the 1990s recession, the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

Deregulating the financial market, floating the dollar and slashing tariffs were a bold departure from traditional Labor orthodoxy. And even more remarkable for a Labor government - the introduction of a centralized wage fixation (the Prices & Incomes Accord).

The unusual marrying of progressive ends (compulsory superannuation) and market-based means later became known in Labor parlance as “the Third Way” as a new generation of pragmatic social democrats like Tony Blair’s “New Labor” joined the throng of economic rationalists and their conservative counter-parts in thrall of the new neoliberal doctrine.

But the “Third Way” was not the silver bullet for distributing wealth and opportunity it was cracked up to be. The price to pay for bipartisanship was that it limited opportunities for disenfranchised voters to voice an alternative opinion, resulting in a further decline in party membership. With debate stifled, the policies of smaller parties also failed to get oxygen.

By the 1990s, it became clear that major parties in advanced Western democracies were, indeed, moving to consolidate the power of their party elites against ordinary members (significantly through changes to rules governing voting and funding systems). It also spelled doom for new challengers. But with the recent rise of social media, especially citizen journalism and Twitter, Australians now have their own political platform, encouraged by the “new media” (the 5th estate) such as Independent Australia.

Are you feeling partied out? How many more times do you think you can bear hearing “Stop the Boats” before being driven to commit axe murder on your neighbour? It feels like we’re drowning in party politics: party slogans, party rhetoric, party policy, party doctrine. As political scientist, Dean Jaensch,describes it - it’s all-pervasive:

‘The forms, processes and content of politics - executive, parliament, pressure groups, bureaucracy, issues and policy making - are imbued with the influence of party, party rhetoric, party policy, party doctrine.’

And dominating the party system for the last seventy years are the Labor, Liberal and National parties (the latter generally in coalition). Is it any wonder we feel wearied?

Relief in the form of minor parties can be momentary, such as the Australian Democrats, who have come and gone. The longest surviving of the minor parties, the Australian Greens, have an uphill battle to get a seat in the House of Representatives because of classical “cartel” collusion by the major parties. Adam Bandt, the only Greens MP in the lower house, looks set to lose his seat if the federal Liberals follow the lead of their Victorian counterparts in preferencing Labor, as they did at the 2010 state elections.

But whilst the major parties may have imposed critical policy on the community’s behalf for nearly a century, Ian Marsh (cf. Part 1) warns that their sway over the community is weakening.

That is certainly the case with falling party membership. No-one is more secretive about party membership than political parties. But there is plenty of anecdotal evidence that suggests rank and file members of the two major parties are voting with their feet.

At a recent birthday lunch of a friend, a former Labor MP, I was given first-hand evidence. Wrongly assuming my fellow guests were all ALP members, I learned they were, in fact, disaffected ALP members. They resigned (as they were at pains to inform me) because they no longer had a say and resented being relegated to mere foot soldiers:

“These days all they want from us is to hand out ‘how to vote’ cards. It was different in Whitlam’s day when we first joined.”

Whilst several had said they’d joined the Greens, when asked who they’d vote for if we had a U.S. Presidential-style election, the response was unanimous: community hero, “Tony Windsor”.

Windsor is a great advocate for community consultation and has now convened three Vision New England Summits where the community gets plenty of say on issues such as broadband, health and education. So, at least the people of New England will have a choice at the Federal election: someone who has not only listened to their needs but ours as well (NBN, action on global warming, protecting our water resources from CSG mining) or the National’s Barnaby Joyce who will be listening instead to the National’s paymasters, the mining industry. (More on this later when we look at who the farmers’ real friends are these days.)

As PM Julia Gillard and Tony Abbott know only too well, the public has stopped listening. But why wouldn’t we give up when neither the government nor the coalition listen to us?

Labor’s ‘brains trust’, its strategic thinkers like Barry Jones, Steve Bracks, Neville Wran, Bob Hawke and father-figure, John Faulkner, have been banging their heads against a brick wall to get this very point across and save Labor from a potential cataclysmic wipe-out.

In Coming to the Party – Where to Next for Labor?, Barry Jones identified the problem in a nutshell: factions. There were two classes of membership in the ALP, said Jones: the faction members who enjoyed a fast track to political jobs and pre-selections and non-factional members who had to fend for themselves. The ALP, he concluded, had been privatised. Its stakeholders were the factions, run by professional managers whose interests had more to do with tribalism and turf wars than policy.

Jones saw a parallel in the declining membership of the party and unions:

‘Both have been slow to adapt to changing social circumstances; both share, in various degrees, an aversion to democratic member participation; both have hierarchies often seen as out of touch.’

Nearly ten years later, little has changed. The 2010 Bracks Faulkner Carr Review was scathing about the contempt in which rank-and-file members are held by factions. A staggering 3,500 members and supporters volunteered to contribute. One after another, the message was hammered home - that branches and members had become irrelevant to Head Office.

The review’s conclusion was that Labor had to modernize its vision and purpose, broaden participation in the Party, give members a greater say and improve dialogue between progressive Australians and progressive third party organisations.

But at the 2011 ALP National Conference, the Right faction torpedoed that idea.

The factional boneheads at Sussex-Central are now engaged in another act of mutually assured destruction with the latest outbreak of hostilities this time by the Left in response to Sam Dastyari’s, promise to run rank-and-file pre-selections in NSW. If the polls prove correct, the spectre of the last remaining NSW faction member in the guise of Python’s Black Knight looms large.

We may see Coalition MPs threatening to cross the floor as they did over the proposed party funding bill, but the cartelization of the Liberal party is just as easy to track. Along with its unpopular factions (which the Liberal Party likes to deny), the hollowing out of their membership base can also be traced to a move away from small “l” liberalism to the right and its embrace of neo-liberalism. The meaning of neo-liberalism has changed over the years, but the Liberal (read Institute of Public Affairs) brand is that social welfare creates dependency, taxation saps business enterprise and governments should corporatise. Potential party members looking for better health, education and transport should apply elsewhere.

As a former director of a board chaired by Sir Rupert (Dick) Hamer, (Liberal Premier of Victoria 1972-1981), I vividly recall Dick bemoaning the fact that he no longer recognized his own party. Dick was an environmentalist and no environmentalist worth their salt would dream of voting for the Liberal Party now. Many former members left in disgust because, like Malcolm Fraser, who resigned, they believed the party had lost its way on global warming.

In an interview in The Conversation, in October 2011, entitled ‘We’ve lost our way’, Fraser said:

“I believe Australia ought to act. We would have had agreement and no still rancorous debate, if Malcolm Turnbull had stayed in charge.”

It’s important to look at the role neo-liberalism and vested interests have played in the cartelization of the Liberal Party.

A fundamental reason for Germany and the U.K. emerging as the leaders on climate action is that neither has a powerful fossil fuel lobby intent on subverting the democratic process. In Australia, like the U.S., the fossil fuel lobby has used its massive war chest to bankroll the Liberal and National parties and wage a hyperbolic war against scientific consensus on global warming. This phony campaign by global warming denialists was, in turn, aided and abetted by a complicit media, the Murdoch press.

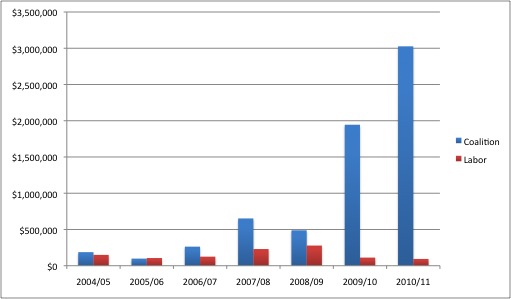

In an article in Crikey on 21 February, 2012 entitled The Rise and Rise of Mining Donations, Bernard Keane presented a graph showing how funding from the fossil fuel lobby to the Liberal National Party has increased exponentially following Labor’s victory in 2007 and the introduction of both a price on carbon and a minerals tax (see below). Keane writes:

‘The sheer scale of mining company generosity illustrates why Tony Abbott remains committed to repealing the carbon pricing package and the mining tax.’

He might also have added that if Abbott wins office on September 14, we will no longer have a democracy but an oligarchy – a government run by powerful mining and media magnates looking for a return on their investment – with George Pell as spiritual adviser. As Keane tweeted recently:

“Australians are a bunch of sheep about to hand themselves over to a pack of wolves”.

Malcolm Fraser was just as scathing about Liberal party factionalism in his interview with Robyn Eckersley. One of the problems, said Fraser, is that:

“…independent people are no longer elected to the parliament. However good she (Kelly O’Dwyer) is, to have only one credible candidate standing for the seat of Higgins was an absolute disgrace for the Liberal party.”

In an essay in the Monthly in May 2011, Peter van Onselen looked at the future of the Liberal Party and whether generational change will bring reform. He disagreed with deputy leader in the Senate, George Brandis (one of the few moderates left) that the factions are clearly conservative or moderate but saw them rather as generational and state-based.

What is clear is that the Liberal Party membership is shrinking. A 2008 internal review of the Liberal Party in what was formerly its most powerful base, Victoria, showed membership was down to just 13,000 members from a peak in 1940 of 46,000. As the median age five years ago was sixty-two, it is likely to have shrunk a lot further.

The story is the same with the National Party. The transition from its traditional farming base to mining apologist has cost it dearly in membership.

These days, if you are crop farmer on the Liverpool Plains or Cecil Downs threatened by expansion of the CSG industry, your best friend is likely to be the Greens (or more recently Katter’s Australian Party) dating from the time the National Party started taking serious donations from the mining industry, the largest being from Clive Palmer’s Mineralogy back in 2009/10. According to a report in Crikey, it represented 20 per cent of the National’s fundraising that year.

In an interview with NSW Green’s MP, Jeremy Buckingham, reported in Independent Australia in February, he told me the NSW public can no longer distinguish between government, lobbyists and the industry because of the revolving door culture of self-interest on both sides of politics.

Consider the following examples of why many farmers in NSW no longer trust the Nationals:

John Anderson, former Deputy Prime Minister and Leader of the Nationals under the Howard Government, served as Chair of Eastern Star Gas (acquired by Santos Ltd).

Mark Vaile, who followed Anderson as Deputy Prime Minister and Leader of Nationals, turned up on the board of Aston Resources – now merged with Whitehaven Coal.

Then you have former high-ranking politicians like Ian Armstrong (former Deputy Premier in the Fahey Government and Leader of the Nationals) in influential roles where they have facilitated mining serving on consultative committees.

The Greens and Katterites plan to offer a real alternative to disgruntled country as well as city voters. Both will field candidates in all 150 House of Representative seats as well as all states and territories in a plan to wedge Labor and LNP by taking on mining interests and warding off CSG mining from prime cropping land. (Full story here).

Katter’s Australian Party has already taken its first LNP scalp. Katter believes he’ll pick a Senate seat from the Nationals in Queensland and possibly one in NSW.

Greens leader Christine Milne is convinced CSG will be a big election issue. Milne, who points out she grew up on a dairy farm, told me in an interview for Crikey:

“It’s extremely serious from a number of points of view. We shouldn’t be starting a new fossil fuel industry at the end of the fossil fuel age. Issues of this century are food and water security.”

It’s hardly surprising that with such widespread dissatisfaction, membership of the major parties has been scuttled and Australia is now home to more non-party independent politicians per capita than any other comparable western country. According to Brian Costar and Jennifer Curtin, in an updated extract from their book, Rebels with a Cause: Independents in Australian Politics (UNSW Press):

‘Since 1990 an unprecedented sixty-six independents have served in the lower houses of Australian parliaments; twenty-two of them are still there.’

As Costar and Curtin point out, over the last two decades, independents have held the balance of power in New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory.

The times may well be right for an independent “movement”. We shouldn’t forget that the very first government after Federation was a loose alliance of independents and fairly broad-based parties where members of parliament voted according to their conscience and the wishes of their constituents.

For those who haven’t visited our “About” page, Independent Australia believes in a fully and truly independent Australia, a nation that determines its own future, a nation that protects its citizens, its environment and its future. True democracy is no longer possible in Australia under the current cartel party system, which exercises strict party discipline to maintain power, sidelines any challengers and subverts the will of the people. This is why Independent Australia is opposed to partisan politics and supports Independent politicians. (Read more here.)

A bottoms-up process where ideas are gathered and concerns heard can only happen through real community engagement. There has surely never been a better time for independents to fill the vacuum vacated by the two major parties. If you’re interested in standing as an Independent, we, at Independent Australia, are willing to assist.

Or, if you’d like to help break the stranglehold political parties have on the throat of our democracy, read managing editor, David Donovan’s, idea of an “anti-party” and contact him by emailing [email protected].

- By John Richardson at 15 Jun 2013 - 12:39pm

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

1 hour 32 min ago

2 hours 5 min ago

2 hours 27 min ago

2 hours 46 min ago

2 hours 57 min ago

15 hours 46 min ago

16 hours 2 min ago

17 hours 48 min ago

18 hours 31 min ago

23 hours 14 min ago