Search

Democracy Links

Member's Off-site Blogs

pulling handles ....

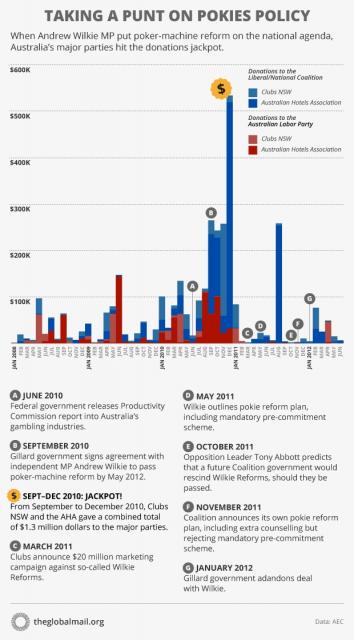

Charting the campaign donations of clubs and pubs that depend on poker-machine profits suggests a formula for gaming politics.

Precisely why would a big donor give thousands of dollars to an Australian political party? The question was considered by the Prime Minister’s department in a 2008 Green Paper on electoral reform.

Refreshingly free of cynicism, the authors suggested that some corporations might direct their hard-earned profits to Labor or the Liberals out of “altruism, or a sense of social responsibility”. Alternatively, they speculated, it could be “the hope of access to the party that wins government, [or] a desire to maximise their profits”.

But mostly they noted the lack of evidence on the subject; unsurprisingly, large donors are not forthcoming about what they hope to secure by filling the coffers of Australia’s major parties.

Which makes the candour of former Clubs NSW chief executive Mark Fitzgibbon all the more remarkable. In 2009, some years after he had left the organisation, Fitzgibbon admitted that Clubs NSW’s political fundraising largesse had a distinct purpose. And it was not altruistic.

“There was absolutely the view that supporting fundraising helped our ability to influence people,” Fitzgibbon told The Australian newspaper.

“We did support political party fundraising, which was a legitimate activity, and it certainly assisted us in gaining access,” he said.

His words shed light on the pattern of political donations these past three years, as Australia’s clubs, and their fellow purveyors of poker machines in the pub industry, poured unprecedented sums of money into the political process, just as threats to their business were massing.

In 2010 the Productivity Commission illustrated Australia’s gambling obsession in extraordinary figures: that Australians lost about $19 billion per year gambling, and that much of this - some 41 per cent, in the case of poker machines - drawn from problem gamblers.

Troubling statistics, and dangerous ones for the industry.

The 2010 federal election only added to pubs and clubs’ worries, bringing two anti-pokies campaigners, independents Andrew Wilkie and Nick Xenophon, into seats in the House and Senate. When Wilkie tied his support for the minority government’s very survival to passing extensive poker machine reforms, the stage looked set for change.

The industry responded with a masterful, multi-million-dollar public lobbying campaign run by club lobby group Clubs NSW, and its pub counterpart the Australian Hotels Association, which targeted and turned wavering Labor MPs against the so-called Wilkie Reforms, and eroded parliamentary support for harm-reduction measures, such as mandatory pre-commitment, of which polls suggested most Australians approved. Mandatory pre-commitment would have required punters to nominate how much they’d lose in a given session, and then be locked out when they hit the limit.

For the detail of how they did it, see James Panichi’s brilliant piece for Inside Story.

But there was another, less public front in the poker machine industry’s campaign against the Wilkie Reforms too, which shows in the political donation records of the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC).

Shown above is every registered political donation made by pubs’ lobby group the Australian Hotels Association, and its clubs counterpart Clubs NSW between 2008 and 2012. Most industries tend to cluster their donations around federal elections, when parties are hungriest for cash. Not so for the poker machine industry. Much like the machines they operate, there’s no discernable pattern to when the lobby groups will pay out.

But there was a clear and dramatic spike in 2010.

Unusually, it did not come before polling day, as is the usual pattern with donations. The federal election in August registered just a small bump in donations.

However by September, when most other business donors had tapered down their election gift-giving the figures for the poker machine industry began to swell.

The AHA gave more than $235,000 that month. Then a similar amount in October. And then a whopping, half-a-million dollar Christmas bonus in December. Clubs NSW also gave with unprecedented generosity over the period, handing out nearly $200,000 in November 2010.

Together, they gave more than $1.3 million in donations for the final quarter of the year. By an overwhelming margin these were directed at the Coalition.

What happened that September? A hung parliament had left the question of who would govern Australia unanswered, while Julia Gillard and Tony Abbott wrangled over the unaligned MPs. On September 2, Gillard won the independent Wilkie over to her side with a pledge to implement his poker-machine reforms.

A deadline was set: Australia’s fragile 43rd parliament would have to tackle the issue by May 2012.

The industry saw the Wilkie Reforms as an existential threat, trumpeting that they would cost $3 billion to implement and cost clubs and pubs 40 per cent of their revenue. Certainly, if there was ever a time to gain access to political leaders and ply influence over policy, this was it.

Wilkie’s plan never reached parliament. The Coalition opposed it from the start, and Labor’s support was always grudging; Gillard abrogated the deal with the Tasmanian independent, instead casting in her government’s lot with a chequered, little-known backbencher named Peter Slipper.

Did the donations play a part in the failure of the Wilkie Reforms? We can’t say for sure.

Nearly a decade after the forthright Mark Fitzgibbon left Clubs NSW, his successor, Anthony Ball, says that under his watch political donations are used only to “politically network”. He told The Australian that the organisation would “absolutely not” use money to influence policy.

So, guess we have to put that enormous spike in donations down to coincidence.

What do you reckon are the odds on that?

- By John Richardson at 17 Aug 2013 - 11:05am

- John Richardson's blog

- Login or register to post comments

Recent comments

3 hours 30 min ago

13 hours 40 min ago

15 hours 32 min ago

15 hours 34 min ago

16 hours 39 min ago

19 hours 59 min ago

1 day 3 hours ago

1 day 3 hours ago

1 day 4 hours ago

1 day 4 hours ago